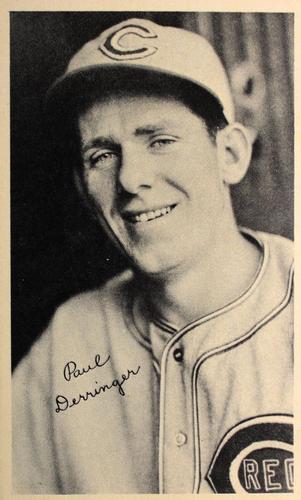

Paul Derringer

To discuss Paul Derringer is to discuss two men-a pitcher with exceptional control of his pitches and general work on the mound and a man with little or no control of himself anywhere else.

To discuss Paul Derringer is to discuss two men-a pitcher with exceptional control of his pitches and general work on the mound and a man with little or no control of himself anywhere else.

Derringer (called “Oom Paul” for his 6-foot-3.1/2-inch height and admitted 205 pounds) was a belligerent man who often used his fists to settle disputes. Sometimes it could be grotesque, like the time he woke up from an operation in the recovery room, swung at a nurse, and knocked her cold. Finding out what he’d done, he apologized profusely. That was not the case in other altercations, as he often wound up in court.

His most egregious fracas occurred on June 27, 1936, at the Bellevue Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia. Robert Condon was at the hotel trying to get the American Legion Convention to come to New York. In Condon’s words, “I had gone to Philadelphia at the request of Mayor LaGuardia to have the American Legion Convention come to New York the next year and was entertaining the secretary of war other guests and their wives in my suite. There was a knock on the door, I opened it and this man was standing there. He was obviously under the influence of liquor and was in his shirtsleeves. He wanted to know why my party was so exclusive. I told him that it wasn’t but that he couldn’t come in. I tried to shut the door and he hit me behind the ear and then began jumping on me. He almost tore my clothes off and my wristwatch was broken. I was laid up for eight weeks and lost possible earnings of $10,000.”

Derringer denied everything. His side of the story was that the man tried to invade his room and that he only gave him a shove to keep him from entering. Condon had a judge issue an arrest warrant on Derringer whenever he would come to New York. Coincidentally, Derringer was selected to pitch in the All-Star Game in New York that year, and it was doubtful if he would show up because of the warrant. Derringer eventually lost the case and was ordered to pay $8,000 in damages. With the suit settled Derringer pitched in the All-Star Game. The Reds helped Derringer by paying part of the damages, but Derringer paid the greater part but, more important, avoided prison.

Derringer had two other nicknames, neither particularly flattering: “Dude” or “Duke” because of his efforts to maintain a sharp sartorial presence. The Dude was rumored to make as many as five changes of clothes in a day. So obsessed with his appearance was Derringer that he often started the day with an informal lounging outfit for breakfast.

On the mound, however, he was in total control, walking only 761 batters in 3646 innings, a mere 1.88 per nine innings. In 1939 and 1940 he led the National League in fewest free passes allowed per nine innings (1.05 and 1.46, respectively). Paul had such command of his pitches that he was called ‘The Control King.” He was known as a great spot pitcher able to put the ball in unhittable places, a description somewhat belied by his giving up more than a hit per inning. In addition to his fastball and curve, Derringer also from time to time mixed in a knuckle ball.

Like a number of good pitchers before and after him, he pitched for some weak teams and absorbed more than his share of losses. For example, he suffered through a disastrous 7-27 mark with the Cardinals and Reds in 1933 despite a 3.30 ERA that was just below the league average of 3.33. He followed that up in 1934 by finishing 15-21 with a 3.59 ERA that was considerably better than the league average of 4.06.

The 1933 season was painful for Derringer, who took losing hard, but he was becoming very important in reviving Cincinnati aspirations toward a better future. His 27 losses were especially frustrating, for the team rarely produced many runs for him. In one fit of temper, he almost killed Larry MacPhail, the Cincinnati general manager. MacPhail was reading Paul the riot act for not sliding on a close play at home plate. Derringer, tiring of the tongue-lashing, picked up an ink well on MacPhail’s desk and threw it at MacPhail, barely missing him. MacPhail said, “You might have killed me, Derringer.” “That’s what I was meaning to do,” was Derringer’s reply. MacPhail, never at a loss for words and actions, took out his checkbook and wrote a check to Derringer for $750 with a note that read, “Thank you for missing my head.”

From 1935 to 1940, as the Reds improved, Derringer turned in slates of 22-13, 19-19, 10-14, 21-14, 25-7, and 20-12. Becoming one of the dominant pitchers in the National League, he helped lead the Reds to league pennants in 1939 (when they were swept by the Yankees in the Series) and 1940 (when they defeated the Detroit Tigers). Derringer won the seventh game of the 1940 World Series when he outpitched Bobo Newsom of the Tigers for a 2-1 win and the title.

Paul was the starting pitcher in the first night game ever played in the major leagues on May 24, 1935, when the Reds hosted the Philadelphia Phillies. Derringer won that game, 2-1. (Jean Derringer, Paul’s niece, recalls somewhat hazily her parents taking her out of school for a 300-mile drive to Cincinnati to see her uncle pitch in the first night game in major league history. She confessed she did not know the significance of that game until many years later.) The floodlights, as they were known, paved the way for the average guy who had to work during the day to see a ballgame, and 20,422 fans attended that historic game.

Derringer remained with the Reds through the 1942 season until on January 27, 1943, he was sold to the Cubs. In his final season, 1945, he went 16-11 to help the Cubs reach their (as of 2004) last World Series. Despite the early terrible seasons, he wound up with 223 wins against 212 losses and a respectable 3.46 ERA.

Samuel Paul Derringer was born in the small town of Springfield, Kentucky, on October 17, 1906. The early settlers came to the town on the Long Beach River by the storied Cumberland Trail on the Wilderness Trace. Springfield is 54 miles southwest of Lexington. Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks, parents of Abraham Lincoln, lived near Springfield. Paul’s father Samuel P. Derringer was of German extraction; his mother was Irish. Samuel was a tobacco farmer and a businessman. Samuel Derringer played semi-professional baseball but turned down an offer from the Louisville Colonels to stay in his business as a tobacco farmer.

Young Paul was a catcher on his high school team at Springfield High and also a three- letter man playing on the football team and the basketball team. According to Bob Considine, he became a pitcher when he asked to pitch a game so that he could speed it up and go on a planned fishing trip.

Paul started his professional baseball career at Danville in the Three-I League in 1927 and 1928. In 1927 Derringer appeared in 26 games, winning 10 and losing 8, working 172 innings with a 3.35 ERA. In 1928 Derringer was 15-11, toiling 243 innings with a 3.67 ERA. The next two years he was with Rochester, winning a total of 40 and losing 23 in 533 innings of work.

In 1931, Derringer was in the spring training camp of the St. Louis Cardinals. In his first assignment, according to Bob Considine, Derringer strode to the mound, his jaw grimly set with the intention of showing just how good he was. On his very first wind-up Paul lifted his leg so high his spikes were caught in the webbing of his glove, and when he attempted to follow through he tumbled off the mound to the delight of everyone. But young Paul showed his stuff and impressed Branch Rickey so much that Rickey gave him a spot on the pitching staff and sent Dizzy Dean to the minors in order to retain Derringer. The move was a wise one, for Derringer won 18 and lost 8 that year with a 3.36 ERA and helped the Cardinals to win the 1931 pennant. Things deteriorated in the World Series against the A’s. Paul struggled and lost two games in 12-2/3 innings. The slump continued in 1932, and he was 11-14 with the Cardinals with a 4.05 ERA. Paul, never a man to take things lightly, began to have skirmishes with the Cardinals front office. This got him a ticket to Cincinnati on May 7 1933, as he was traded with Sparky Adams and Allyn Stout for Leo Durocher, Dutch Henry, and Jack Ogden.

Earlier on, Paul had almost escaped what was then called the “St. Louis Chain Gang.” He was promised that at the end of 21 days he would get a bonus of $2,500 and a salary of $750 a month if he made good, or released if he did not make the grade. Rickey never showed up at the end of twenty-one days and not for days after that deadline. Enter Cy Slapnicka of the Cleveland Indians. Slapnicka told Derringer he liked him and would sign him. Slapnicka wrote out a bonus check for $5,000 and promised a monthly salary of $1,000. Slapnicka told Derringer to pack his bags at night and slip out the back of the hotel where he would be waiting with his car. Derringer slipped out all right, right into the waiting arms of coach Bill McKechnie of the Cardinals, who was having a smoke. “Where do you think you are going?” asked McKechnie. After Derringer told McKechnie what was going on, McKechnie took Paul to the club secretary and demanded the right to sign Derringer and give him the promised bonus.

Dizzy Dean and Derringer never liked each other, and this resulted in a fight between the two before a game in June of 1939, when the Cardinals were visiting the Reds. Punches were swapped, and then they wrestled each other to the ground where they were separated by other players and sent to their respective dugouts. Derringer’s teammates said that Dean had been riding Paul for quite a while.

Out of the majors in 1946, Derringer was pitching for the Indianapolis team in the International League. That was the year Jackie Robinson was with Montreal. When Indianapolis met Montreal early in the season, Paul was the starting pitcher and told his old friend Clay Hopper, the Montreal manager, that he was going to knock Robinson down, “To see what makes him tick.” The first time he knocked Robinson down Jackie lined the next pitch for a single. The next time Jackie came up Derringer nearly hit him in the head. Later in the count Jackie lashed a triple to deep left. After the game Derringer approached Hopper and said, “he will do.” Hopper then notified Branch Rickey that Robinson was ready.

Paul Derringer, a small-town man from Kentucky, joined fellow Kentuckians Earle Combs and Pee Wee Reese in becoming major league stars. He had instant success in his rookie year in the majors but slipped a bit and then regained his form to win 223 games. He was hot tempered at times, but on the mound he exhibited great control.

Perhaps indicative of his difficult personality, Paul was married three times. Vera Trent, whom he married on September 13, 1928, divorced him on March 26, 1936. On October 17, 1937, he wed Eloise Brownback and was divorced from her on August 16, 1944. The marriage produced daughter Leda Eloise, born on June 28, 1938. Derringer contended in his divorce suit that Eloise had tossed a highball into his face after an argument about who made a better drink. On September 3, 1944, he married Mary Jane Stein.

While still pitching, Paul was living in West Frankfort, Illinois, where he was in the drugstore business with his brother-in-law Carl Barker. After retirement Paul worked as a plastics salesman and also worked for the American Automobile Association as a trouble-shooter taking care of matters such as bail. He was living from hand to mouth when he died on November 17, 1987, in Sarasota, Florida, at the age of 81. Mary Jane had passed away 16 years earlier, on December 3, 1971. Paul left behind five children, including his oldest daughter, Leda Eloise.

Sources

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: The Free Press, 2001.

Matz, David S., and John L. Evers. “Derringer, Samuel Paul ‘Duke.’” David L. Porter, ed. Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball. Revised and expanded edition. Westport, Connecticut, and London: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Neft, David S., Richard M. Cohen, and Michael L. Neft. The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball 2000. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2000.

Paul Derringer files at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York.

Full Name

Samuel Paul Derringer http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695

Born

October 17, 1906 at Springfield, KY (USA)

Died

November 17, 1987 at Sarasota, http://dev.sabr.org/afl/ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.