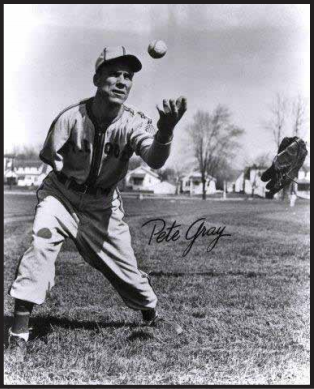

Pete Gray

Baseball is a difficult game to play well for those with two good arms but Pete Gray did it with one. Gray played only one season in the major leagues, 1945, but that was enough to have a lasting positive influence on people with disabilities. His accomplishment enlightened those of us who are perfectly formed, too —and it redefined how we view people with disabilities. Gray’s feel-good story was cathartic to a war-torn country, especially to disabled servicemen returning from World War II. His achievement was due to his incredible focus and determination. Gray became famous, but he was also “manipulated by club owners as well as by the media, maligned by many of his teammates, and left to wonder just how good a player he really was.”1 He deferred praise for his bravery to soldiers who had served on the battlefield. Gray spent his later years in obscurity and poverty and he would later say that he hadn’t done enough, given the opportunities he had, to help disabled people. There was one youth, however, Nelson Gary Jr., a 3-year-old, whom Gray met and befriended, and the two became forever linked by the coincidence of losing their right arms.

Baseball is a difficult game to play well for those with two good arms but Pete Gray did it with one. Gray played only one season in the major leagues, 1945, but that was enough to have a lasting positive influence on people with disabilities. His accomplishment enlightened those of us who are perfectly formed, too —and it redefined how we view people with disabilities. Gray’s feel-good story was cathartic to a war-torn country, especially to disabled servicemen returning from World War II. His achievement was due to his incredible focus and determination. Gray became famous, but he was also “manipulated by club owners as well as by the media, maligned by many of his teammates, and left to wonder just how good a player he really was.”1 He deferred praise for his bravery to soldiers who had served on the battlefield. Gray spent his later years in obscurity and poverty and he would later say that he hadn’t done enough, given the opportunities he had, to help disabled people. There was one youth, however, Nelson Gary Jr., a 3-year-old, whom Gray met and befriended, and the two became forever linked by the coincidence of losing their right arms.

Pete Gray was born Peter J. Wyshner Jr. on March 6, 1915, in the rural Hanover district of Nanticoke, in Pennsylvania’s Wyoming Valley, 20 miles from Scranton. He was the youngest of five children, two girls and three boys, born to Lithuanian immigrants Peter and Antoinette (Keulewicz) Wyshner.2 The children were Ann, Rose, Joseph, Anthony, and Pete Jr. Peter and Antoinette, the parents, emigrated from outside of Vilna, Lithuania, and lived in Chicago before moving to Nanticoke in 1911. They wanted a better life, a higher standard of living, and working in the burgeoning coal industry offered them the opportunity to achieve it. They worked for the coal-mining operations of the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad, the largest employer in the region. These companies exploited Eastern European families for their cheap labor. Peter Sr. began working in the mines as a laborer. Antoinette was eager for the family to earn enough money to purchase a house and buy fine things. She would have liked to work but there were few jobs for women and those that were available paid very little. She asked her husband to see if he could obtain extra work in the mine to earn more money. When he hesitated, she dressed as a man and went to work in the mines for almost a week before being caught.3

The girls attended school until the eighth grade and then provided domestic services for the family. The boys attended school until they turned 13 years old and then went off to the Truesdale Colliery of the DL&W to work.4

Gray was 6 years old when he lost his right arm in an accident while hitching a ride on the running board of a produce truck. The driver had to stop suddenly and Gray fell off and got his right arm caught and mangled in the spokes of a wheel. He was rushed to the hospital but his arm could not be saved and it was amputated above the elbow. Gray had been right-handed before the accident. He learned to use his left arm to do everything.

Gray’s family downplayed the loss of his arm and treated him like any other child his age so that he would learn to be independent. Gray shared the same dream as many other kids—to grow up and become a great baseball player one day… unlike most kids, he never gave up the dream. He worked incredibly hard and set off to accomplish what most people thought impossible.

Playing baseball was not just fun but the most popular way for immigrant children to assimilate into their new culture. Pete said he knew he had a better eye than most kids and just had to learn to hit left-handed. He practiced with a rock and a stick every day for hours to “develop a quick wrist.”5 Hitting was the easiest part of baseball for him. Fielding and throwing were more difficult because he had to perform four more steps than a two-armed player.

“I’d catch the ball in my glove and stick it under the stub of my right arm. Then I’d squeeze the ball out of my glove with my arm and it would roll across my chest and drop to my stomach. The ball would drop right into my hand and my small, crooked finger prevented it from bouncing away.”6 If Gray couldn’t execute these extra steps quickly and precisely than all would be for naught—he would be allowing runners time to take an extra base.

“Eventually he learned that by removing almost all the padding from his glove and wearing it on his fingertips with the little finger purposely extended outside of the mitt, he was able to catch the ball and get it to his throwing hand in one swift motion. He credits the success of the entire maneuver to his little finger, which was bent upwards at almost a right angle.”7

At the age of 17, Gray hitchhiked from Nanticoke to Chicago to watch the 1932 World Series. He claimed to have experienced a personal turning point there when he witnessed Babe Ruth’s “called shot” home run. He figured that Ruth hit it because he had confidence in himself and that if he himself had the same degree of confidence that Ruth had, then he would play in the major leagues one day.

In 1934 Gray started playing for what had once been his neighborhood church team, the Lithuanian Knights, which had become a semipro team called the Hanover Lits that competed all across the Wyoming Valley. A Sunday afternoon game would draw 2,000 to 3,000 people. In their first year in the league the Lits finished 3-11. Gray’s older brother Tony was a pitcher on the team. Gray was fearless and often crowded the plate. If a pitcher aimed a ball at his head, his mother was the first one to reach the mound. Teammates said Gray took after his mother.8 The following year the Lits jumped to the Luzerne County League but a miners’ strike canceled the season. In 1936 the team added players of all ethnicities and changed its name to the Hanover Athletic Association.

Gray played center field and hit third in the lineup. He reached an adult height of 6-feet-1 and a weight of 169 pounds. He had an unusually strong arm—both his forearm and bicep were oversized as the result of his working out with weights, and this enabled him to swing a 38-ounce bat, heavier than average. He was a good fastball hitter and possessed excellent speed—he stole a lot of bases. His aggressiveness on the bases cost him the season, though, when he tried to steal third base with a head-first slide and fractured his collarbone. In Gray’s absence, brother Tony pitched and hit Hanover to the league title.

The two again figured prominently in their team’s success in 1937. In one game, Pete got four hits and four RBIs in a victory against arguably the best pitcher in the league, a fellow named McLaughlin. Hanover captured its second title. The local leagues no longer offered Gray a challenge. He felt he needed to look further than the Wyoming Valley. He began calling himself Pete Gray instead of Pete Wyshner. He thought it would make things simpler to use a non-ethnic-sounding name. He took the idea from his oldest brother, Joseph, who had fought as an amateur boxer between 1921 and 1928 under the name Whitey Grey. In 1938 Pete played for semipro teams in Pine Grove and Scranton in the hope of getting noticed by the Boston Red Sox, who had a farm team in Scranton. To no avail. He attended tryout camps, with the Cardinals for instance, but all they did was watch him in the batting cage for a few minutes before dismissing him.

A friend gave Gray a letter of introduction to visit Connie Mack but Gray couldn’t get a tryout. “Son,” Mack said, “I’ve got men with two arms who can’t play this game.”9 According to a friend, scouts not only underestimated Gray’s physical abilities but also his heart.10

In 1940 Gray left Pennsylvania for New York and a tryout with the legendary semipro club the Brooklyn Bushwicks. When owner/manager Max Rosner scoffed at his request for a tryout, Gray “handed him a $10 bill saying, ‘Keep it if I don’t make good.’”11 Rosner accepted the offer. Gray played in a game that day before 10,000 fans and had two hits, one a home run, and received $25 from Rosner. Crowds increased and Gray held out for more money. He received $350 per month—all for playing Sunday doubleheaders. Gray tried to enlist shortly after Pearl Harbor but was rejected because of his missing arm. Gray played for the Bushwicks for two seasons and compiled a .350 batting average. A scout for the Three Rivers (Quebec) club in the Canadian-American League who knew Gray from Pennsylvania wired his boss praising Gray.

The scout signed Gray but failed to tell his boss that Gray had only one arm. The owner almost fainted when he saw Gray but he had faith in his scout. Gray’s debut couldn’t have gone better if it were scripted in Hollywood. The crowd chanted for Gray the whole game. With Three Rivers trailing archrival Quebec 1-0 in the ninth and the bases loaded, Gray was called in to pinch-hit. With the count 2-and-1, Gray singled and everybody started throwing money at him. After he scooped it up he counted over $100.

Gray was doing well but opponents began making adjustments. They knew he could hit the fastball so they threw him off-speed pitches. Gray tweaked his batting stance to speed up his bat and generate more power. Runners began taking advantage of the time it took for Gray to get the ball into the infield. He made adjustments to his fielding by tossing the ball up in the air, discarding his glove, and returning the ball to the infield. He lost a third of the season with another broken collarbone but finished the season with a batting average of .381 in 160 at-bats. The Canadian-American League canceled the 1943 season. Gray went to spring training with the Toronto Maple Leafs but was released before the season. Rumors that Toronto manager Burleigh Grimes didn’t take to him affected Gray’s chances to catch on with another team. However, Mickey O’Neill, Gray’s teammate at Three Rivers, worked to help him find a team and persuaded Doc Prothro, manager of the Memphis Chicks of the Southern Association to sign him.

Gray put on fine hitting displays and played aggressive baseball for the Chicks. The press dubbed him their “One-Armed Wonder.” Prothro liked Gray and admired his all-out style of play. Worried that Gray would injure himself Prothro tried to rest him, but Gray would hear none of it. He didn’t want to let down fans. Fans called the ballpark every day wanting to know if Gray would be playing. It was the same on the road. The Chicks were going nowhere in 1943 but Gray insisted on playing every inning. It took multiple injuries to get him out of the lineup. Prothro thought Gray had a wonderful sense of humor, too. His favorite story about Gray involved a motherly fan concerned about the outfielder’s missing arm.

“Pete was jogging for the locker room to take a cold shower when a lady fan reached over the runway and grabbed him by the shoulder.

“‘Oh, you poor boy,’ she said, ‘playing baseball with just one arm and running and throwing and swinging that bat so hard. It must be an awfully tough job for you.’

“She kept on running like that for three or four minutes. Pete was getting tired of waiting for his shower but stuck it out.

“‘And how did you lose your right arm you poor boy?’ she finally asked.

“‘A lady in Brooklyn talked it off, ma’am,’ Pete responded, and raced off to the showers.”12

The Chicks finished last in the league, with a 56-81 mark, but the year was a tremendous success for Gray. He played in 126 games and batted .289. Philadelphia sportswriters honored him with their Most Courageous Athlete Award. Gray glossed over his own struggles and praised the country’s servicemen.

“Boys, I can’t fight. And so there is no courage about me. Courage belongs on the battlefield not on the baseball diamond. But if I could prove to any boy who has been physically handicapped that he, too, can compete with the best—well then, I’ve done my little bit.”13

Gray was a shy person and did not feel he had done anything to warrant all of the attention he received, but he did his best to show his appreciation to the public and to veterans, especially wounded ones and amputees. He went on USO tours after the season and visited military hospitals and rehabilitation centers and spoke with veterans.

While Gray was playing for Memphis, the team was contacted by Nelson Gary from Van Nuys, California. His 6-year-old son, Nelson Jr., had lost his right arm at age 2 in an electrical accident and he wanted to meet his favorite ballplayer, Gray. The Memphis Commercial Appeal paid their way to come out and meet Gray. The two became friends and corresponded for a number of years. Gray visited Nelson each summer until he was 10 years old.

Gray returned to Memphis in 1944 and had an even better year than in 1943. Playing in 129 games, he batted .333. He stole 68 bases and had 35 extra-base hits, including five home runs, three of which cleared the fences. Scouts from almost every major-league team were following Gray by this time. In late September, the St. Louis Browns acquired his contract him for $20,000, the largest sum paid for a Southern League player to that date.

Despite their success in 1944—they won their first pennant ever —the Browns were not doing well financially and hoped to increase revenues by signing Gray. Manager Luke Sewell promised to treat Gray like any other player and said he would get a fair chance to make the team and earn his playing time. But Sewell knew the fans would demand to see him play.

“I don’t think Luke really wanted him,” recalled Don Gutteridge, the former White Sox manager, who had been among Gray’s St. Louis teammates. “We won the pennant the year before. I don’t think the other players believed he could help us win again.”14

“He was kind of a loner,” Gutteridge said. “He wanted to be known as a ballplayer, not a one-armed ballplayer. He didn’t want to be exploited because he had one arm.”15

Gray played his first game on April 17, 1945, starting in left field at home against the Detroit Tigers. He singled in four at-bats in a 7-1 Browns victory. But after getting just three hits in 21 at-bats, he was benched and played just one game in 16 days. Then he played for about a week but after that his playing time got sporadic.

“Browns teammate Ellis Clary remembered Gray ‘as being ornery as hell. The first time you met him you felt sorry for him, but two hours later, you hated his guts. He was all right, I guess. But he was a strange guy. He didn’t want anyone feeling sorry for him.’”16

Gray was a Yankees fan growing up, and playing against his favorite team meant something special to him. The Browns’ first series against the Yankees, May 18-20 in St. Louis, resulted in a four-game sweep by St. Louis. Gray contributed five hits, all singles, in 15 at-bats, walked three times, had two stolen bases (he was caught stealing once), had three RBIs, and scored three runs. He had a dozen putouts in left field. In the first game of a Sunday doubleheader on May 20, played before a home crowd of 20,507, Gray got three hits in five trips to the plate and played flawless defense in the Browns’ 10-1 win. In the series he raised his batting average from .179 to .225.

Gray always dreamed of playing in Yankee Stadium and he received his chance a week later. He didn’t start in any of the three games, all losses, but he did deliver a pinch-hit single with his parents and a busload of friends from Nanticoke in attendance, and this game meant more to him than any other one in his career. But his playing time then began to diminish.

Gray’s average continued to decline and he played sporadically. In the second week of June Sewell started playing him in center field instead of his usual position in left field. This didn’t sit well with regular center fielder Mike Kreevich, who was struggling, hitting just .237. “An established player—he hit .301 the season before—Kreevich expressed his dissatisfaction. ‘It didn’t suit Mike at all,’ Don Gutteridge recalled. To keep the peace the Browns asked waivers on Kreevich, and on August 8, sold him to the Washington Senators.”17

As Gray’s average plummeted, so did his patience, and he began to argue with umpires. Pitchers realized his vulnerability and changed their approach to pitching to him: They fed him a steady diet of breaking balls or low outside pitches and tight inside ones. He simply couldn’t get his bat around fast enough or stop it once he had committed to a pitch, and they exploited him for it. Runners, especially the faster ones in the league, began to take an extra base on the split-second longer it took for Gray to get the ball back into the infield. The writing was on the wall, his limitations were exposed. Still, Gray had some very good games, and even a modest hitting streak. The seven-game streak, from June 27 through July 5, raised his batting average from .223 to a respectable .260. On August 19 Gray went 4-for-7 with three singles and a double, against the Boston Red Sox in a 13-inning Red Sox victory. He went 3-for-5 against the Yankees on September 15. Altogether Gray played in 77 games and hit .218.

“[Teammate Ellis] Clary also revealed that some of Gray’s teammates, particularly pitchers Sig Jakucki and Nelson Potter, were constantly ragging him. Jakucki once put a dead fish in the pocket of Gray’s new sports coat and Gray knocked him down with one punch. ‘We had to separate them,’ Clary said. ‘He was a tough guy, always ready to fight. He didn’t take any guff from anybody.’”18

Some blamed Gray for the Browns falling out of pennant contention in 1945. They claim that Gray played later in the season when he was not hitting well. That does not entirely make sense. The Browns had a better record when Gray was in the lineup: 33-21 in games Gray started, a .611 winning percentage, compared with their overall winning percentage of .536. During the Browns’ longest losing streak, six games from September 6 to September 9 (including two doubleheaders), Gray was used exclusively as a pinch-hitter and was 0-for-4. The Browns finished in third place with a record of 81-70, six games behind the first-place Detroit Tigers. The team compiled a .249 batting average, next-to-last in the league, while the team ERA was third-best in the league at 3.14. The only teams to post a winning record against the Browns were the Detroit Tigers, who dominated them, winning 15 of 21 games, and the Cleveland Indians, 11-10 against the Browns. For whatever it’s worth, Gray started only five games against the Tigers (the Browns won two) and had single at-bats in two other losses.

With many established major leaguers returning home from the service in 1946, Gray was sent down to the minor leagues. He played for the Browns’ top farm team, the Toledo Mud Hens, in 1946 and batted .250 but sat out 1947 in a salary dispute and was placed on baseball’s suspended list. He remained in Nanticoke and played in the Anthracite League under assumed names for his old Hanover Athletic Association team and two other teams.19 In 1948 he played for Elmira in the Eastern League and in 1949 for Dallas, mostly as a pinch-hitter. With Elmira he batted .290 in 82 games. He barnstormed with teams from 1949 until he retired from baseball in 1953.

Gray returned to Nanticoke where he worked in, and later briefly owned, a billiards parlor. He could shoot pool with the best players and excelled at golf, card games, and checkers. Gray never married. He took care of his oldest brother, Joseph.20

A Winner Never Quits, a TV movie about Gray’s life, debuted in 1986 and starred Keith Carradine. The film implies that Gray’s brother Joseph helped to train Gray but it was actually his brother Anthony who assisted with Gray’s training.21 When one-handed pitcher Jim Abbott made it to the big leagues in 1989, there was renewed interest in Gray.

“Overcoming his physical handicap apparently was easier for Gray than finding a so-called inner peace. But according to [Gray’s cousin,] Bertha Vedor, Gray [then 73] has mellowed with the years. ‘He’s a big hero here,’ she reported. ‘All the kids love him; he’s wonderful with young people.’”22

Nelson Gary Jr., the boy whom Gray befriended, became a talented right fielder for Occidental College. His successful squeeze bunt drove in the winning run for the 1962 Southern California Intercollegiate Athletic Conference Champions.

Gray lived in a nursing home in Sheatown, Pennsylvania, for the last few years of his life. He died on June 30, 2002, and is buried in Saint Mary Cemetery, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

Sources

I am indebted to and wish to thank author William C. Kashatus for his outstanding book, One Armed Wonder: Pete Gray, Wartime Baseball and the American Dream, which was my main source for this biography. Almost all of the facts used in this biography that are not common knowledge are derived from his book. Mr. Kashatus kindly shared his personal insights about Gray with me in a November 2014 email and responded very promptly to my questions.

In addition to the sources noted, the author also accessed Gray’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and consulted Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com.

Crowe, Jerry. “2 Lives Are Linked in Tragedy, Success: Nelson Gary Jr. Had Bitter Times Trying to Follow Path Cut by Hero Pete Gray,” Los Angeles Times, May 4, 1986.

Goldstein, Richard. “Pete Gray, Major Leaguer With One Arm, Dies at 87,” New York Times, July 2, 2002.

Nelson Gary Baseball Speech accessed at youtube.com/watch?v=qxwD3ilT4yg,

Humor Pete Gray may have appreciated: Bill James’ Historical Baseball Abstract, 1985 edition, 86, “The 1940s,” states: “Worst Arm: Pete Gray (sorry).”

Notes

1 William C. Kashatus, One-Armed Wonder: Pete Gray, Wartime Baseball, and the American Dream (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 1995), 3.

2 Antoinette Wyshner’s maiden name as it was reported in Pete Gray’s obituary, Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, July 2, 2002, 10A.

3 Kashatus, 14.

4 Kashatus, 26.

5 Kashatus, 27. Gray quoted in Dallas Morning News, April 10, 1983, 16-B; and New York Daily News, August 7, 1971, 21.

6 Kashatus, 27. Joe Falls, “Once Upon a Time There Was a One-Armed Outfielder … in the Major Leagues,” Sport, January, 1973, 86.

7 Kashatus, 27.

8 Kashatus, 36. Kashatus interview with Tony Burgas, May 30, 1991.

9 Kashatus, 45.

10 Kashatus, 44.

11 Kashatus, 46.

12 Kashatus, 70. Doc Prothro quoted in Detroit Free Press, March 14, 1945, 14, and in Toronto Star Weekly, May, 12, 1945, 12.

13 Kashatus, 71.

14 Jerome Holtzman, “One-armed Pete Gray’s Career Was Short and Bitter,” Chicago Tribune, April 20, 1989. Accessed online December 4, 2014, articles.chicagotribune.com/1989-04-20/sports/8904050969_1_pete-gray-big-league-armed.

15 Holtzman.

16 Holtzman.

17 Holtzman.

18 Holtzman.

19 Email correspondence with author Bill Kashatus, November 9, 2014.

20 The boxing record of Gray’s brother Joseph, who fought under the name Whitey Grey, was consulted by the author at Box-Rec.com. Grey lost his last five fights, two by knockout and one, his last, by technical knockout. Author Kashatus stated that Nanticoke residents insinuated that he suffered damage from boxing and referred to him as being “punch drunk.”

21 Email correspondence with Bill Kashatus, November 9, 2014.

22 Holtzman.

Full Name

Peter J. Gray

Born

March 6, 1915 at Nanticoke, PA (USA)

Died

June 30, 2002 at Nanticoke, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.