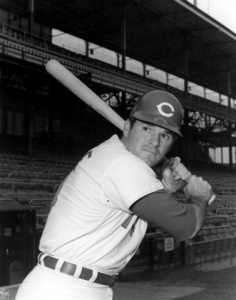

Pete Rose

The 1970 All-Star Game, at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati, was tied at 4-4 with two out in the bottom of the 12th inning. For the National League, Pete Rose was on second base and Billy Grabarkewitz on first. When Jim Hickman lined pitcher Clyde Wright’s offering to center field, hometown hero Rose broke from second base. Rounding third as center fielder Amos Otis came up throwing, Rose barreled toward home plate, but between Rose and home plate stood catcher Ray Fosse, awaiting Otis’ throw. Just as the ball arrived, Rose plowed into Fosse, sending the catcher sprawling with an injured shoulder. Rose touched the plate with the winning run, but not before putting himself and Fosse in harm’s way in what was essentially an exhibition game.

The 1970 All-Star Game, at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati, was tied at 4-4 with two out in the bottom of the 12th inning. For the National League, Pete Rose was on second base and Billy Grabarkewitz on first. When Jim Hickman lined pitcher Clyde Wright’s offering to center field, hometown hero Rose broke from second base. Rounding third as center fielder Amos Otis came up throwing, Rose barreled toward home plate, but between Rose and home plate stood catcher Ray Fosse, awaiting Otis’ throw. Just as the ball arrived, Rose plowed into Fosse, sending the catcher sprawling with an injured shoulder. Rose touched the plate with the winning run, but not before putting himself and Fosse in harm’s way in what was essentially an exhibition game.

Ten years later the Philadelphia Phillies were two outs from the first world championship in their 97-year history, but they were in big trouble. The Phillies were up three games to two and were ahead 4-1 in Game Six, but the Kansas City Royals had loaded the bases with one out on a walk and two hits. Pitcher Tug McGraw’s first pitch to the Royals’ Frank White was popped up foul near the first-base dugout, and catcher Bob Boone rushed over to secure the critical second out. Disaster almost struck. The ball bounced from Boone’s mitt. Just as it was about to hit the ground, Phillies first baseman Pete Rose snatched it from certain calamity, recording the out. McGraw then struck out Willie Wilson to clinch the 1980 World Series title for the Phillies.

Pete Rose is among the most controversial figures in baseball history. His skill, reckless abandon, and desire to win endeared him to millions of baseball fans, but that same hard edge combined with personal missteps to give his detractors more than enough fodder to tear him down. Through baserunning and bravado, girlfriends and gambling, one thing was indisputable: Pete Rose was an outstanding baseball player.

Peter Edward Rose was born on April 14, 1941 at Deaconess Hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio, the third of four children born to Harry Francis Rose and LaVerne Bloebaum Rose. Most friends called his parents Pete and Rosie.1 With his sisters, Caryl and Jacqueline, and his younger brother, David, he grew up in the Anderson Ferry section of Cincinnati. Harry worked for Fifth Third Bank for more than 40 years, but his real claim to fame was as a semipro athlete. He boxed and played baseball, softball, and football well into his 40s. Harry chased all of his athletic pursuits with the same reckless determination that became his son’s hallmark. Harry was determined to make his son an athlete from an early age, and always stressed to him that when you play, you play to win. Pete’s father once told an amateur baseball coach that Pete would play for the team, but only on the condition that he be allowed to switch-hit. He was 8 years old.2

Pete attended Western Hills High School, a local incubator of baseball talent (12 alumni, including Rose and Don Zimmer, played major-league baseball). He excelled in football and baseball. He did not, however, excel in the classroom and as a result was forced to repeat the ninth grade. He could have avoided this fate by attending summer school, but his father objected on the ground that it would take time away from summer baseball.3 Because of this extra year Rose was ineligible to play baseball for Western Hills during his senior season, so he played in a semipro league, where he attracted the attention of scouts. Rose’s uncle Buddy Bloebaum, who had played in the minors and was now a bird-dog scout for the Reds, had made it his goal to have the young Rose sign with the hometown team. On the day that Rose graduated from Western Hills in 1960, Uncle Buddy told the family that the Reds were willing to sign Rose for $7,000 plus another $5,000 if he made the majors. Years later Rose recalled, “I don’t remember ever wanting to be anything but a professional athlete and it’s a good thing I became one because I never prepared for anything else.”4

After signing, Rose reported to the Class D Geneva (New York) Redlegs of the New York-Penn League, where he displaced a young Cuban named Tony Perez at second base. Pete hit .277 in his first professional season. Perez moved to third base and eventually to first, where he joined Rose as one of the key cogs in the Reds machine of the 1970s. After hitting .331 for the Class D Tampa Tarpons in 1961 and .330 with the Single-A Macon Peaches in 1962, Rose was invited to spring training with the Reds in 1963. While there were no great expectations for the young Rose, he impressed with his hitting, and manager Fred Hutchinson had it in mind to keep Rose on the active roster to start the season. Many Reds veterans did not want to see Rose make the squad – he would be replacing their buddy, Don Blasingame – but he hit so well that he gave the team no choice but to take him north.5

Just shy of his 22nd birthday, Rose made his major-league debut by starting on Opening Day 1963 at home against the Pittsburgh Pirates. He started his major-league career 0-for-12 before lining a triple into the gap in left-center field off Pittsburgh’s Bob Friend. Hitting .273 and scoring 101 runs, Rose was named the National League Rookie of the Year. In July he met Karolyn Engelhardt at the River Downs racetrack in Cincinnati, and the two were married. Rose left his own wedding reception in order to attend the Parade of Stars dinner put on by Cincinnati’s baseball writers.6

The 1964 season was not as smooth for Rose (.269, 64 runs scored), but he bounced back strong in 1965 and established himself as one of the better hitters in the National League. He led the league with 209 hits, made his first All-Star Team, and hit .312. It was the first of his 15 .300-or-better seasons.

Through the 1960s Rose continued to establish his credentials as a premier player. He twice led the league in hits (1965 and 1968), led the league in runs scored in 1969, and won his first two batting titles in 1968 and 1969. In 1969 he also won the first of consecutive Gold Gloves as an outfielder, after having moved out of the infield in 1967 and recording 20 outfield assists in 1968.

Rose’s prominence brought his no-quarter-asked-none-given style of play into the spotlight. Perhaps no athlete in any sport has ever squeezed more production out of his ability than Rose, and nobody has ever wanted to win more. Joe Morgan, Rose’s teammate with both the Reds and Phillies, wrote, “Pete played the game, always, for keeps. Every game was the seventh game of the World Series. He had this unbelievable capacity to literally roar through 162 games as if they were each that one single game.”7 Rose was aggressive but smart, possessed superior instincts, and always hustled.8

Perhaps no word is used in connection with Rose more than “hustle.” He knew of its importance to his big-league career, once saying, “I didn’t get to the majors on God-given ability. I got there on hustle, and I have had to hustle to stay.”9 It became an enduring part of Rose’s persona through the nickname that defined him, Charlie Hustle, bestowed upon him by Whitey Ford, who saw him sprint to first after a walk during a spring training game.10 “That’s the only way I know how to play the game” became Rose’s standard response in explaining his approach on the field.11 Los Angeles Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully quipped that Rose “just beat out another walk.”

In many ways Rose was a walking baseball contradiction. He was aggressive and combative on the field, but was accommodating and a great quote for the media. He was selfish—playing for stats, money, fame—but was also unselfish—he always picked up the check, routinely invited teammates to live with him,12 and willingly changed positions several times during his career, all for the benefit of his team or teammates. He loved being around smoke and alcohol, but did not smoke or drink himself.13

As good as Rose had been in the 1960s, the 1970s were even better for Rose and the Reds. Led by new manager Sparky Anderson in 1970 and sparked by the arrival of second baseman Joe Morgan and center fielder Cesar Geronimo in a trade with Houston after the 1971 season, the Reds dominated the National League for most of the decade. Driven by its powerful offense, the Big Red Machine captured four pennants and two World Series titles between 1970 and 1976.

On the field Rose served as The Machine’s leadoff hitter and catalyst, infusing the Reds with his desire to win and intimidating opponents in the process. He caused an uproar before Game Five of the 1972 World Series against Oakland when he intimated to the press that Catfish Hunter wasn’t all that great, then backed up his bravado by homering off Hunter to lead off the game and then getting the game-winning hit in the ninth off ace reliever Rollie Fingers. A year later Rose started a bench-clearing melee in the National League Championship Series against the Mets with a hard takeout slide of Met shortstop Bud Harrelson and wrestling Harrelson to the ground in the ensuing ruckus. Rose’s fire led the Reds on the field, and the group of Rose, Johnny Bench, Tony Perez, and Joe Morgan controlled the clubhouse during the 1970s, in large part with a good-natured humor that left no one immune to serving as the butt of a joke.14

Pete’s finest all-around season was probably 1973, when he won his third batting title (.338), had 230 hits, scored 115 runs and was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player. Despite his personal achievements, the Reds season ended with a Game 5 NLCS loss to Harrelson and the Mets. In 1974 the 33-year-old Rose saw his average dip below .300 for the only time between 1965 and 1979, and whispers began that he was on the downside of his career.

After missing the postseason in 1974, the Reds and Rose came back with ferocity in 1975. He led the league in runs scored and doubles for the second season in a row, and the Reds blew away the National League West with a 108-54 mark. After some early inconsistency at the hot corner, Anderson asked Rose, on May 2, to move to third base for the good of the club—starting the next day. Rose complied, and throughout the remainder of the season he wore out coaches George Scherger and Alex Grammas by having them hit groundballs to him at third.15 Rose was never exceedingly fluid or swift at third, but he was serviceable. The move allowed Anderson to insert slugger George Foster into the Reds lineup in left field, and many have pointed to this as the inflection point when the Big Red Machine became THE Big Red Machine. Rose first took the field at third base when the Reds hosted the Braves on May 3, and from that point through the end of the regular season the team posted a mark of 96-42 (.695) and finished 20 games ahead of the Dodgers.

In the NLCS the Reds swept the Pirates in three games to advance to the World Series against Boston. This Series has gone down as one of the greatest in baseball history, with the high point coming during the epic sixth game that ended with Carlton Fisk famously waving his game-winning home run down the left field line to stay fair in the bottom of the 12th inning. Throughout the see-saw affair, many participants later testified, Rose could not stop babbling, “Isn’t this great? This is the best game I’ve ever played in. Isn’t this great? People will remember this game forever. Isn’t this great?” or other such remarks.16 He repeated this claim to Sparky Anderson after the game, but he also promised his manager that the Reds would win Game Seven.17 The next night the Reds defeated the Red Sox, 4-3, to capture the first World Series championship for the Big Red Machine after Series losses in 1970 and 1972. The title was Cincinnati’s first since 1940, and hometown hero Rose was named Series MVP after hitting .370 with a .485 on-base percentage. Rose later said he never saw the ball better than he did in the 1975 World Series, that it “looked like a beach ball.”18 For Rose, the season was capped in December when Sports Illustrated named him its Sportsman of the Year.

The 1976 regular season played out in a remarkably similar fashion. Rose again led the league in runs scored, hits, and doubles, and posted numbers similar to his 1975 totals across the board. The Reds again won more than 100 games, swept through the NLCS (this time defeating the young Philadelphia Phillies), and swept the New York Yankees in the World Series.

While the Reds looked invincible on the field, the game off the field was changing like never before. Faced with the new economics of baseball in the aftermath of an arbitrator’s decision that granted players the right to earn free agency, Reds general manager Bob Howsam and president Dick Wagner decided not to participate in the competition for players. Faced with the impending departure of free-agent starting pitcher Don Gullett, the Reds traded Tony Perez and left-handed reliever Will McEnaney to Montreal for pitchers Woodie Fryman and Dale Murray. Without Perez, Gullett, and McEnaney, the 1977 Reds slumped to second place. But it would be difficult to lay any of the blame at the feet of Rose. He had his standard season—he played every game, hit .311, and made the All-Star team—but the season was not without some drama. In the aftermath of the Perez trade, Rose and his agent, Reuven Katz, played hardball with the Reds in salary negotiations. He had made $188,000 in 1976, and after watching free-agent Reggie Jackson sign a huge deal with the Yankees, requested $400,000 for 1977. When the team balked, Rose took his case public through the media, expertly explaining his position to the fans, opening up the possibility of playing out his option and hitting free agency if he was not treated fairly, and galvanizing public opinion behind him. Eventually, on the eve of the 1977 season Rose signed for two years at $752,000, far more than the $425,000 the team had originally offered.19

Rose continued to pad his baseball rėsumė. In 1977 he passed Frankie Frisch’s record for the most hits by a switch-hitter, and then on May 5, 1978, with a single against the Montreal Expos, became the 13th major leaguer to get 3,000 hits. Greeting him at first base after the milestone hit was his old pal Tony Perez. Pete notched two hits at home against the Cubs on June 14, and proceeded to get a hit in each of the next 43 games, offering what remains through the 2011 season as the most serious threat to Joe DiMaggio’s record 56-game streak. When the streak reached 30 games the national media began to descend upon him and, ever the quote machine, offered, “Fine with me. I like talking about my base hits.”20 Over the course of the streak Rose hit .385 with 18 multihit games and struck out only five times in 182 at-bats. He passed Tommy Holmes’s 37-game mark from 1945 to set a new National League record, and was not stopped until after 44 games he went 0-for-4 on August 1 in Atlanta as Gene Garber struck him out to end the game. The Reds again finished second in the NL West. After the season Sparky Anderson was fired, and Rose, with his two-year contract expired, was allowed to enter free agency.

By most accounts Rose wanted to remain in Cincinnati for the rest of his career, and Katz, his agent, had even floated the idea of a lifetime contract. The Reds were not interested, so it was pretty well understood that Rose would leave Cincinnati. While it would be hard to argue that his play on the field had declined, Rose at this time was in the middle of a nasty divorce, and his hard lifestyle and even alleged associations with gamblers made the decision for the Reds to move on a bit easier.21

On the open market Rose had no shortage of suitors, and the bidding war that developed for his services included various enticements. August Busch, Jr., owner of the St. Louis Cardinals, offered Rose his own beer distributorship; Pirates owner and horse farmer John Galbraith offered race horses; and Ewing Kauffman of the Kansas City Royals offered stock in his pharmaceutical company.22 However, one team had caught Rose’s eye as early as 1976: the Philadelphia Phillies. When the Big Red Machine squared off with the Phillies in the 1976 NLCS, Rose opined to Joe Morgan, “That team’s got talent. All they need is a leader.”23 After losing to the Reds in the playoffs in 1976, the Phillies won the NL East again in 1977 and ’1978, only to lose the NLCS to the Dodgers both times. With the Phillies desperate to get over the hump and win their first World Series in franchise history, Rose seemed a natural fit, but it appeared that the Phillies could not afford him. Seeing an opportunity for a mutually beneficial relationship, Phillies executive Bill Giles asked the local television station that carried their games, WPHL, for an additional $200,000 in broadcasting rights fees if the team signed Rose, anticipating increased viewership. The station agreed, and on December 5, 1978, Rose signed with the Phillies for four years and $3.2 million. (The Phillies sold $3 million worth of tickets in the next 30 days.24) Still at issue was what position Rose would play; the Phillies’ best player was third baseman Mike Schmidt, a brilliant hitter and fielder. A spring-training deal sent first baseman Richie Hebner to the New York Mets, opening a spot for Rose, who to this point had played three games at first in his career.

The 1979 Phillies slumped to a fourth place finish, but Rose more than held up his end of the bargain. He hit .331 with a league-leading.418 on-base percentage and a career-high 20 stolen bases. In the midst of a late-season slide, the Phillies fired manager Danny Ozark and replaced him with their high-strung scouting director,, Dallas Green. Green had been a pitcher for the Phillies in the 1960s and had given up Rose’s only grand slam, a fact that Rose often reminded the manager of.25

In 1980 the Phillies returned to the postseason and, after a subpar – for him – regular season (.282), the NLCS gave Rose the stage to show exactly why he had been brought to Philadelphia. With the Phillies trailing the Astros in the best-of-five series two games to one, Rose singled with one out in the top of the tenth inning. After an out, Greg Luzinski ripped a ball into the left-field corner and Rose broke from first determined to score the go-ahead run. He tore around third, casting nary a glance at third-base coach Lee Elia, and rumbled towards home and Astros catcher Bruce Bochy. “I know Pete Rose,” said Joe Morgan, now playing again for the Astros, “Pete Rose was never going to stop.” As the relay from shortstop Rafael Landestoy neared the plate, Rose unloaded a forearm to Bochy’s jaw as the ball bounced away. Rose scored the go-ahead run and the Phillies closed out the game in the bottom of the inning.

The next night in the winner-take-all Game Five, the Phillies were down 5-2 in the top of the eighth inning against Nolan Ryan. With the bases loaded and no outs, Rose stood in against Ryan and the two baseball legends engaged in an epic seven pitch at-bat with Rose ultimately earning a walk and an RBI to cut the lead to 5-3 and chase Ryan from the game. For once Rose did not sprint to first base, but arrogantly threw his bat toward the dugout and stared out at Ryan as he swaggered down to first. Philadelphia ended up taking a 7-5 lead, gave it up in the bottom of the inning, and finally won it in the tenth to clinch their first pennant in 30 years. While second baseman Manny Trillo was named the NLCS MVP, Rose reached base 13 times in 25 plate appearances, and his attitude energized his team. The Phillies dispatched the Royals in six games to win their first World Series in the team’s history, and Rose’s purpose for signing with the Phillies was fulfilled.

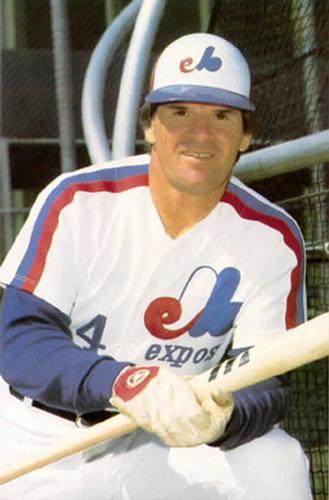

Rose broke Stan Musial’s National League hits record in the first game back after the end of the 1981 player strike, and hit .325 for the season. After two subpar seasons for the club, the Phillies acquired 41-year-old Tony Perez and 39-year-old Joe Morgan to join the 42-year-old Rose on the Phillies for the 1983 season. The team was dubbed the Wheeze Kids, a takeoff on the Phillies’ youthful 1950 pennant winners, the Whiz Kids. After the Phillies sputtered to a record just above .500 halfway through the season, manager Pat Corrales was replaced by Paul Owens. From that point, the Phillies raced ahead of the pack, winning the East by six games. Rose was hitting only .248 at the end of August, and his playing time was diminished significantly during the stretch drive in favor of rookie Len Matuszek. Rose hit only .220 in 50 September at-bats. Due to roster rules at the time, Matuszek was ineligible for postseason play, and like an old warhorse on its last charge at the enemy, Rose hit .344 in nine postseason games as the Phillies beat the Dodgers in the NLCS before losing to Baltimore in the World Series. Three days after the World Series ended, Rose was released by the Phillies.

Perhaps needing a gate attraction more than a 43-year-old hitter, the Montreal Expos signed Rose in January 1984. He played in 95 games for the Expos, then was traded back to Cincinnat on August 16, where he became player-manager. Rose played at first base and as a pinch-hitter, in pursuit of Ty Cobb’s major-league hits record. He reached that milestone on September 11, 1985, at home against the Padres with a looping single to left off Eric Show for the 4,192nd hit of his career. As fans stood and cheered and teammates swarmed around him, Rose tearfully embraced his 15-year old son, Pete Jr., in the area around first base.

Perhaps needing a gate attraction more than a 43-year-old hitter, the Montreal Expos signed Rose in January 1984. He played in 95 games for the Expos, then was traded back to Cincinnat on August 16, where he became player-manager. Rose played at first base and as a pinch-hitter, in pursuit of Ty Cobb’s major-league hits record. He reached that milestone on September 11, 1985, at home against the Padres with a looping single to left off Eric Show for the 4,192nd hit of his career. As fans stood and cheered and teammates swarmed around him, Rose tearfully embraced his 15-year old son, Pete Jr., in the area around first base.

Rose played through the 1986 season, but never officially filed for retirement. His accomplishments were staggering. As of 2011 he was the leader in hits, games played, at-bats, plate appearances, singles, and times on base. He was second in doubles and sixth in runs scored, and retired with a lifetime .303 batting average. He won an MVP, a World Series MVP, a Silver Slugger award, and two Gold Gloves. His teams won six pennants and three World Series.

Rose stayed on as manager of the Reds through the beginning of the 1989 season, by which time his life had become very interesting. He had been suspended for 30 days in 1988 for shoving umpire Dave Pallone, but what sat before Rose a year later was far more serious. Allegations arose that he had bet on major-league games in violation of the sport’s most sacred rule. Commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti retained John Dowd to investigate the matter, and the Dowd Report was presented to Giamatti in May. The report’s most stirring conclusion was that Rose had in fact bet on baseball during his tenure as Reds manager. In late August 1989, Rose and Giamatti agreed to a settlement in which Rose would be declared permanently ineligible from baseball, with the ability to ask for reinstatement after one year. Meanwhile, Rose steadfastly maintained that he had not bet on baseball

Less than a year later, in April 1990, Rose pleaded guilty to charges related to income-tax evasion and served five months in the federal penitentiary in Marion, Illinois. After the tax due, interest, and fees had been paid, he was released from prison in January 1991.

Being placed on the permanently-ineligible list barred Rose from attending official ceremonies, with the exception of the All-Century Team presentation during the 1999 World Series. His number 14, which certainly would have been retired by the Reds, has been issued by the team only once since his banishment, and that to his son Pete Rose, Jr. during the younger Rose’s brief tenure with the club in 1997.

After 15 years of vehemently denying that he had bet on baseball, Rose, in his book My Prison Without Bars (2004) admitted that he had. However, even this could not be done without controversy, as the book coincided with the announcement of that year’s Hall of Fame class.

In 2016, an unidentified woman alleged that in the 1970s she engaged in a sexual relationship with Rose before she turned 16 years old, an allegation that amounts to statutory rape in most states. Rose acknowledged the relationship but denied knowing she was younger than 16. Rose filed a defamation suit that a judge dismissed after both parties reached an undisclosed settlement.

In his 70s and still a fixture at baseball card and autograph shows, Rose spent more than 20 hours a week greeting fans and signing autographs at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas for much of the decade of the 2000s. So long as the individual paid the autograph fee, Rose would sign anything, including the Dowd Report and his mug shot from his tax-evasion charges.26

It’s all part of the hustle.

Postscript

Rose died at the age of 83 on September 30, 2024.

Notes

1 David Jordan, Pete Rose: A Biography (Chicago: Greenwood, 2004), 3-4.

2 Joe Posnanski, The Machine (New York: William Morrow, 2009), 129.

3 Jordan, Pete Rose, 5.

4 Jordan, Pete Rose, 7.

5 Greg Rhodes & John Erardi, Big Red Dynasty (Cincinnati: Road West Publishing, 1997), 23-24.

6 Jordan, Pete Rose, 26.

7 Joe Morgan and David Falkner, Joe Morgan: A Life in Baseball (New York: W.W. Norton, 1993), 285.

8 Rich Westcott and Frank Bilovsky, The Phillies Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004), 244.

9 Westcott and Bilovsky, The Phillies Encyclopedia, 244.

10 Pete Rose and Roger Kahn, Pete Rose: My Story (New York: Macmillan, 1989), 9.

11 Mark Frost, Game Six (New York: Hyperion, 200), 59.

12 Bob Molinaro, telephone interview with author, May 27, 2011.

13 Posnanski, The Machine, 91-95.

14 Robert “Hub” Walker, Cincinnati and the Big Red Machine (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1988), 68.

15 Rob Neyer and Eddie Epstein, Baseball Dynasties (New York: W.W. Norton, 2000), 314.

16 Posnanski, The Machine, 3.

17 Rhodes and Erardi, Big Red Dynasty, 216.

18 Frost, Game Six, 265.

19 Rose and Kahn, Pete Rose, 180-185.

20 Rhodes and Erardi, Big Red Dynasty, 280.

21 Rhodes and Erardi, Big Red Dynasty, 286.

22 Bill Giles with Doug Myers, Pouring Six Beers at a Time (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2007), 131-132.

23 Giles, Pouring Six Beers at a Time, 121.

24 Giles, Pouring Six Beers at a Time, 133.

25 Frank Fitzpatrck, You Can’t Lose ‘Em All (Boulder, Colorado; Taylor Trade Publishing, 2001), 74.

26 Posnanski, The Machine, 266-275.

Full Name

Peter Edward Rose

Born

April 14, 1941 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

September 30, 2024 at Las Vegas, NV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.