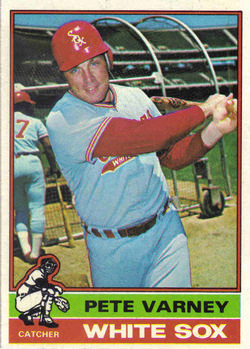

Pete Varney

Even if Pete Varney had never strapped on a chest protector and shin guards for Harvard, he would have had a place in the hearts of the Crimson sports faithful forever from one momentous football game in 1968. But baseball was his game, as he gained All-American recognition and led Harvard into the 1971 College World Series. Then, after six seasons of professional baseball, buffeted by player-management turmoil and the vicissitudes of serving as an MLBPA player representative, he turned to coaching and became a living New England legend at Brandeis, where he mentored and led the Judges’ baseball team for 34 seasons before retiring in 2015.

Even if Pete Varney had never strapped on a chest protector and shin guards for Harvard, he would have had a place in the hearts of the Crimson sports faithful forever from one momentous football game in 1968. But baseball was his game, as he gained All-American recognition and led Harvard into the 1971 College World Series. Then, after six seasons of professional baseball, buffeted by player-management turmoil and the vicissitudes of serving as an MLBPA player representative, he turned to coaching and became a living New England legend at Brandeis, where he mentored and led the Judges’ baseball team for 34 seasons before retiring in 2015.

Richard Fred (“Pete”) Varney Jr. was born on April 10, 1949, in Roxbury, Massachusetts, one of the 23 officially-recognized neighborhoods in Boston.1 He is the sixth of nine children of Richard F. (“Pete”) Varney Sr. and Eileen Collimore Varney, both natives of Massachusetts with English-French ancestral roots. The senior Varney worked as a roofer, became a union representative, and ultimately vice president of an international roofers’ union.2 Eileen kept the family home. Pete, who inherited his father’s nickname as a youngster and still uses it, with “Richard” lost to time, was the couple’s third son; he had five brothers and three sisters. 3

By the time the younger Pete, who filled out to six-foot-three and 235 pounds in his baseball prime, was a three-sport high school athlete, the Varney family lived in Quincy, a sizeable suburb just south of Boston. In 1964, when he was just fifteen and a sophomore, Pete was starring in varsity baseball, football, and basketball for North Quincy High. As a 17-year-old senior in the spring of 1966, his solid catching skills, power, and .480 batting average from the right side of the plate were already attracting serious attention from professional baseball scouts.4 Seeing a standout prospect in a power-hitting catcher, the Kansas City Royals selected Pete as their number-one overall pick in the August 1966 Legion draft.5 He didn’t sign, but this was only the first of the seven times he would be selected in the draft, never lower than the third round, over the next five years.

Pete enrolled at Deerfield Academy, an elite preparatory school in northwest Massachusetts, for the 1966-67 year. There, while honing the leadership and academic skills that had made him an honor roll student and president of the senior class at North Quincy High, he continued to play baseball and football. 6 He was selected to the second team of the Boston Globe’s 1966 all-prep football team as a halfback.7 His prowess as a catcher garnered him selections by the Houston Astros in the first round of the January 1967 draft and the third round of the June 1967 draft.

Once again, Varney bypassed professional baseball, spending the summer of 1967 playing for the Massachusetts Envelope team in the suburban Boston Park Baseball League.8 He entered Harvard that fall with a concentration in American history. A “standout” fullback on the 1967 Crimson freshman football team, he also played freshman baseball in the spring of 1968. 9 He moved up to playing end on the varsity football team as a sophomore that fall.10

On November 23, 1968, Varney caught one of the most memorable passes in the venerable history of Harvard-Yale football. With time expired on the Harvard Stadium clock, Varney grabbed a two-point conversion pass from Frank Champi to end the game in a 29-29 tie.11 12

That sophomore glory was the apex of Varney’s football career, but he was just getting started in baseball, as he continued to catch and play first base under coach Loyal Park. As a senior in 1971, Varney hit .362, was named the catcher on the American Baseball Coaches Association All-America first team, and led Harvard into the College World Series, where the Crimson beat Brigham Young before losing to Tulsa and being eliminated by Texas-Pan American.

During his three years on the Harvard varsity, Varney had been selected in three more drafts, by the Washington Senators, San Francisco Giants, and finally the Atlanta Braves in the January 1971 secondary draft.

But he stayed in school, earned his B.A. degree, and graduated in the spring of 1971.13 Varney then stopped “ignoring the bundles of money offered by major league baseball scouts since starring at North Quincy High School, and headed for a pro career.”14 The Chicago White Sox, through scout Ben Huffman, were the successful suitors, selecting Varney first overall in the June 1971 secondary draft. Boston sports attorney/agent Bob Woolf handled the negotiations for Varney and told writers, “The contract is very lucrative and contains a substantial signing bonus.”15

The Dallas Cowboys had shown interest in signing Varney as a free agent, but “baseball is my first love,” Varney said. “As a catcher I think it will take me a couple of years. I’m willing to put in the time in the minor leagues.”16

Given his collegiate experience, the White Sox started Varney in Double-A, where their 1971 Asheville (North Carolina) Tourists farm club was competing in the East Division of the far-flung Dixie Association under manager Larry Sherry.17 The 22-year-old arrived on July 20, well after the Dixie season had started. He got off to an excellent start in his first game, with two singles, a run scored, and an RBI.18 But he cooled after that and hit .187 in 111 plate appearances in 37 games.19

Varney and Martha Sue “Marti” Wettergreen of Wakefield, Massachusetts, announced their engagement in August 1971 while he was with Asheville. They were married at Harvard Memorial Chapel in Cambridge on November 27, 1971.20

White Sox management was concerned about Varney’s hitting at Asheville, where the bandbox proportions of the ballpark, McCormick Field, can make it a productive haven for line-drive hitters.21 When Varney reported for his first spring training at minor-league camp in Sarasota in March 1972, Sherry, Varney’s manager in Asheville, had been promoted to manage the Tucson Toros, the Sox’ AAA affiliate in the Pacific Coast League. “This spring I thought [Varney] would have to go back to AA ball for sure, but by the end of spring training he impressed me so much I took him along as my catcher,” Sherry said.22 On his adjustment from college to professional baseball, Varney added, “I think the experience at Asheville helped me tremendously. I feel a lot more comfortable around the guys. My mental approach is much different.”23

Throughout his career, as one-handed catching with enlarged, hinged mitts started to come into vogue, Varney continued to use the classic two-handed catching style with a round (“donut”) mitt, “even when catching Wilbur Wood,” a knuckleball pitcher.24

Varney did the bulk of the Tucson catching in 1972, delivering a solid defensive season and hitting .234 with 42 RBIs in 393 plate appearances. As the season progressed, Sherry moved him from eighth in the batting order to the middle. “I think he’s had some better pitches to hit; he has a quick bat,” the skipper reasoned.25

It was a change in leagues and managers for Varney in 1973: the Sox moved him to the Iowa Oaks in the AAA American Association, where his manager was Joe Sparks. Varney continued to improve. He was hitting .251 with 18 home runs and 50 RBIs, enroute to a selection as the catcher on the All-Star team, when an injury to Dick Allen in late August resulted in his promotion to the White Sox.26

Varney got a start in his major league debut game — the second game of an August 26 doubleheader against Detroit at White Sox Park. Catching lefty starter Terry Forster and slotted eighth in the batting order, he lined out to left field against Woodie Fryman in the second inning, worked a two-out walk off Fryman in the fourth, then reached again on an error in the sixth before manager Chuck Tanner replaced him as Detroit came to bat in the seventh. He caught the later innings of four more games and picked up two more at-bats without a hit over the rest of the season.

Despite the limited late-season opportunities Varney got with the fifth-place White Sox in 1973, Chicago suburban columnist Mike Klein tabbed the 24-year-old “perhaps the best young ChiSox catcher.”27 He had enough value that when veteran Ron Santo told the Cubs in December that he would not play for them in 1974 and sought a trade to the Sox, Varney was among a group of seven players offered by the Sox from which the Cubs could choose any four for the rights to Santo.28 The Cubs selected younger catching prospect Steve Swisher and three pitchers, Ken Frailing, Steve Stone, and Jim Kremmel, and Santo closed out his 15-year major league career with the White Sox. The club signed Varney to a 1974 contract in late February during spring training in Sarasota.29

Even with Swisher gone, the White Sox deemed their 1974 catching “so adequate that huge Pete Varney probably will go back to the minors again.”30 He was optioned back to Iowa in early April.31 The actual move was delayed; Varney stayed on the major league roster until the end of the month because backup catcher Chuck Brinkman was injured. Varney, “tied with Brian Downing for the No. 2 catcher spot,” didn’t get into a game with the Sox, and by April 24 was back with the Iowa Oaks. 32 33

There, he posted the best statistical season of his career, batting .274 in 390 plate appearances, with 16 home runs and 72 RBIs. He once again defended excellently at a .993 clip with 51 assists and only 4 errors in 572 chances.

The White Sox again promoted Varney to the big club, this time a little earlier in the season, and he started the second game of a doubleheader against the New York Yankees at Shea Stadium on August 16, 1974. 34 Batting eighth, he wasted no time getting his first major league hit, a third-inning single off Dick Tidrow. He successfully navigated Sox pitchers Jack Kucek and Stan Bahnsen to a 4-2 win that bumped Chicago a game over .500 at 60-59. Spelling catchers Ed Herrmann and Downing, he got six more starts over the rest of the season as the Sox, 80-80, finished fourth in the American League West. Varney had two hits in a win at Oakland on September 27 and finished the season at .250 in 30 plate appearances.

Varney was assured of a spot on Chicago’s 1975 season-opening roster when late in spring training the Sox traded Herrmann, the team’s player representative, to the Yankees. That move installed Varney as a solid backup for Downing, who moved in as starter behind the plate. Tanner started Varney 27 times, often when Jesse Jefferson started; Jefferson preferred Varney over Downing because he provided a bigger target.35 Varney marked a personal milestone on August 19 with his first major league home run, off Larry Gura of the Yankees at Shea Stadium in a 7-6 Sox win.

Later in that 1975 season Varney mused with Chicago Tribune writer Bob Verdi: “I just happen to be one ballplayer who decided all along that I wanted to get my college education over with before I went into [professional] sports.” Then the Boston-area native turned a bit philosophical. “I like Chicago and I like playing there. But it would be kind of fun to play for the Red Sox someday. That’s the kind of town you get attached to. I was sitting in the bleachers there in 1967 when the Red Sox won it all. I said to myself then I’d do anything to be a part of baseball. Now that I am, some days when I’m running in the outfield I take a look at the bleachers and see a lot of kids who are probably thinking the same thing.”36

The Sox kept Varney in the majors for the entire 1975 season and he took on their player representative duties on June 15 when incumbent Stan Bahnsen was dealt at the trade deadline. In 114 plate appearances Varney hit .271 but, usually batting ninth in the order, wasn’t a power or run-producing threat. He had two home runs and eight RBIs for the season.

The 1976 season brought changes to the Chicago organization and to baseball which, at least indirectly, had a significant impact on Varney’s career. During the offseason White Sox owner John Allyn sold the club to the mercurial Bill Veeck, who replaced Tanner with Paul Richards as manager. Then, baseball arbitrator Peter Seitz adjudicated the simmering issue of player free agency by striking down baseball’s reserve clause, which had bound a player to an organization in perpetuity. The move rankled baseball ownership and made service as a team’s player representative an especially hazardous undertaking, with freshened animosity between management and players. Both Varney’s immediate predecessors as player representative, Herrmann and Bahnsen, had been sent away in 1975 trades, and Varney had accepted the position “with reluctance” when Bahnsen left.37 Varney had served without incident through the rest of 1975, but given White Sox management’s recent record, was a man on the spot when the free agency decision was announced in 1976.

Exacerbating this pressure, Richards, an opinionated 67-year-old who had spent his eight-year major league career as a catcher, while conceding that Varney was “a good handler of pitchers,” added, “but we still have to work on his throwing.”38 This ominous message came in early May. Varney was hitting .333 in limited action, but the fates of Herrmann and Bahnsen in Chicago hung in the background. At the June 15 trading deadline, Varney himself was gone, traded to the Atlanta Braves for well-worn 31-year-old pitcher Blue Moon Odom, who had been demoted to Atlanta’s AAA Richmond farm club at the time of the trade.

Varney had been popular as a hard worker with his teammates, some of whom took the move personally. “I can’t understand it. I lost a hell of a lot of respect for this organization with that move,” pitcher Dave Hamilton said. “They say Pete’s going to the minor leagues, but I can’t believe they couldn’t find a place for him in the majors,” pitcher Bart Johnson added. An unnamed player summed it up: “He got screwed because he was the player rep. That’s the surest way to get traded.”39

Varney was indeed assigned to the minors — the International League Richmond Braves — immediately after the trade, but got a brief stint in Atlanta shortly after arriving in Richmond when backup catcher Biff Pocoroba went on the disabled list.40 “I knew I was only up here for a short time, but I was hopeful, anyway,” Varney told an Atlanta writer on the eve of his return to Richmond. Early in the interview he refused to assign any blame for the Chicago trade, staying positive. “I’ll never really know the inside story. The White Sox have a good organization. I was disappointed when I got traded. It was tough for me to change allegiance. I grew up with the guys in that organization. I had an allegiance with them.”41

At the end of the interview, though, he became more introspective. “I thought my career had progressed very rapidly. Getting into the big leagues was a battle, but I had thought I had progressed nicely. Then this year the White Sox got a new manager and I had to prove myself all over again. Now I must do it again. I’d like to know what I’ve done to deserve this.”42

Varney had 121 plate appearances in 34 games for Richmond in 1976. The Braves recalled him in late August and manager Dave Bristol gave him starts on September 6 and 12 during a west coast road trip. In the second inning of the September 6 game, Varney got his sole National League hit, a single off John D’Acquisto of the Giants.

Varney presciently experimented with coaching during the 1976-77 offseason. “I couldn’t find enough time for basketball at Harvard, but every year [when] I come home from baseball I play basketball. It’s a terrific way to stay in shape and it beats running past the same trees every day,” he told a writer for the Lowell (Massachusetts) Sun.43 He had seen a newspaper advertisement for coaching the junior varsity basketball team at Littleton (Massachusetts) High School, applied, and got the job. Although the prior year’s team had finished 0-16 and Varney’s was 1-6 through the first seven games, he was characteristically upbeat about his players: “They have improved 1,000 percent since I’ve had them because they’re really dedicated.”44

Varney spent the 1977 baseball season back with Richmond, sharing time with the Braves’ top catching prospect, 21-year-old Dale Murphy, and hitting a creditable .285/.367/.456 with 10 home runs and 41 RBIs in 80 games. Richmond, at 71-69, sneaked into the International League playoffs but was ousted by the Pawtucket Red Sox in the first round. Varney’s solo home run was the only run Richmond scored in losing the second game, 4-1, on September 7.45

With Murphy in the system, Varney didn’t get a late-season call to Atlanta. The organization released him to free agency prior to the 1977 minor league free agent draft, but he wasn’t selected.46 Near the end of 1978 spring training he was still listed as unsigned.47

Varney turned 29 that April. For the first time since 1968 he wasn’t set to play collegiate baseball or due at a professional training camp, so over the 1977-78 winter he returned to Littleton High School to coach the junior varsity basketball team. He put his Harvard degree to use too, taking a job teaching in Wayland, another community in Middlesex County, Massachusetts.

But baseball was in Varney’s blood. He played in the highly competitive summer Boston Park League. He turned his coaching interest to baseball and coached at Narragansett High School in Templeton, Massachusetts, for three years.48 Then, when Tom O’Connell, who had coached the NCAA Division III Brandeis Judges baseball team since 1973, stepped down at the Waltham school after the 1981 season, Varney took over as baseball coach on February 9, 1982.49 O’Connell had led the school to six consecutive NCAA regional appearances 1975-80, with a second-place Division III World Series finish in 1977. Varney, who kept his eye on local talent with his summer Pete Varney Baseball School, maintained O’Connell’s recruiting quality, leading the Judges to a 23-13-1 record in 1982, his first season, as Brandeis made the regionals again. Eleven more regionals followed, and Brandeis went to the Division III World Series in 1999. Over Varney’s 34-year tenure at the helm, his Brandeis teams played postseason baseball in 21 seasons and won two Eastern Collegiate Athletic Conference (ECAC) titles.50

Because no athletic scholarships are awarded in NCAA Division III, it isn’t known for producing players who make the steep climb to the major leagues, but Varney coached one. Nelson Figueroa, class of 1998, debuted in the majors with the Arizona Diamondbacks in 2000 and went on to a nine-year career as a pitcher with the Phillies, Brewers, Pirates, Mets, and Astros. Five of Varney’s players — Bryan Haley at Endicott, Eric Podbelski at Wheaton, Mike Connolly at Bowdoin, Bob Rikeman at Rollins, and Derek Carlson at Roger Williams University and ultimately Varney’s replacement at Brandeis — went on to college coaching jobs of their own.51 Ten more went into high school baseball coaching.

Varney, who notched his 700th coaching win on April 7, 2015, finished with a 705-528-6 record at Brandeis when he retired later that year. “It has been a wonderful journey watching all the young men arrive on campus as freshmen, and then witnessing their development into mature, successful men,” he said.52

University senior vice president Andrew Flagel summarized what Varney, who as a young man had recognized the importance of an education despite the lucrative temptations of signing early as a top draftee, meant to his players over the years: “I have spoken with many of our alumni from the team, hearing story after story of the way that Brandeis baseball and Coach Varney changed their lives. Players from past decades continue to credit Pete with their success, both on and off the field.”53

Varney was honored as All-New England Baseball Coach of the Year in 1987. He was inducted into the Harvard Varsity Club Athletic Hall of Fame in 1996 and the New England Intercollegiate Baseball Association Hall of Fame in 2018.

Although Pete follows Brandeis and college baseball in retirement, he has not followed the professional game since he ended his career. He and Marti continue to live in Acton, Massachusetts. They have two sons, Chris and Steven. Chris, recently married to the former Kate Perch, is an engineering graduate of Tufts University and works for Hyde Construction Company in Belmont, Massachusetts. Steven was an all-Ivy League football player at Dartmouth College and has an MBA degree from the Tuck School of Business there. He works in the financial service industry and is married to his high school sweetheart, the former Jen Martin. They have three children.54

Last revised: July 12, 2019

Author’s note and acknowledgments

The inspiration for this biography was George Howe Colt’s The Game: Harvard, Yale, and America In 1968 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018). While Pete Varney, with whom I wasn’t familiar when I read the book, wasn’t one of the primary focuses of the book, the author’s mention of Varney’s having played major league baseball intrigued me to further research, and I discovered his interesting story.

Pete Varney graciously reviewed the manuscript of this biography and provided details and insight in a telephone conversation and e-mails. My SABR colleagues Bill Nowlin and Kevin Larkin assisted me — Bill by coordinating with Pete Varney in Boston, and Kevin by reviewing Pete Varney’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

The biography was reviewed by Warren Corbett and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the Sources cited in the Notes, I used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for player, team, league, and season pages as well as daily player and team logs and other resources.

Notes

1 BostonPlans.org/neighborhoods, accessed November 27, 2018.

2 E-mail from Pete Varney, March 20, 2019.

3 “I’ve been known as Pete for as long as I can remember,” Varney told an Iowa sportswriter in 1973 as he was progressing through the minor leagues. Ron Maly, “Harvard Catcher for Oaks,” Des Moines Tribune, April 9, 1973: 25.

4 Kevin Walsh, “Varney Rates High With Pro Scouts,” Boston Globe, May 29, 1966: 36.

5 The August Legion Draft, for players who had participated in summer baseball leagues, was held only in 1965 and 1966. Baseball Draft item, Baseball-Alamanac.com, accessed November 27, 2018.

6 Walsh, “Varney Rates High.”

7 Boston Globe, December 11, 1966: 68.

8 Boston Globe, August 18, 1967: 26.

9 Boston Globe, December 19, 1967: 51.

10 The NCAA limited college freshman football and basketball players to freshman teams until 1972. The eight-member Ivy League conference, of which Harvard has been a member since the formation of the League in its current iteration in 1956, did not permit freshman to play varsity football until the 1992 season. Bruce Berlet, “Ivy League Football Coaches Adjust to Freshman Eligibility,” Hartford Courant, reprinted in Los Angeles Times, September 18, 1993, http://articles.latimes.com/1993-09-18/sports/sp-36313_1_ivy-league-football, accessed November 27, 2018.

11 Harvard had scored a touchdown on the play that ran out the game clock to make the score 29-27, Yale. Under NCAA rules Harvard was permitted a conversion attempt as a result of the touchdown despite no time on the clock.

12 Depending on one’s orientation toward either Harvard or Yale, this was the famous — or infamous — game which produced the “Harvard Beats Yale, 29-29” headline in the next day’s Harvard Crimson newspaper. Chelsea Janes, “Throwback Thursday: Harvard ‘Beats’ Yale, 29-29,” Washington Post, November 14, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/dc-sports-bog/wp/2014/11/20/throwback-thursday-harvard-beats-yale-29-29/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.6b4146e46409.

13 Varney had a student deferment from the military draft during his years at Harvard. His birthdate was assigned No. 218 in the Vietnam War-era draft lottery; the number never came up in the lottery draws. E-mail from Pete Varney, March 20, 2019.

14 AP, “Harvard’s Pete Varney Signs; Comes to terms with Chicago,” Lowell (Massachusetts) Sun, July 13, 1971: 17.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 The 1971 Dixie Association was a one-year Double-A league with three divisions and teams spread from Savannah, Georgia, to Albuquerque, New Mexico. Asheville had been a member of the Southern League in 1970, but that circuit had a one-year hiatus in 1971, when Asheville played in the Dixie Association. The Southern League resumed play in 1972 with Asheville as a member, although Asheville had switched its affiliation from Chicago (AL) to Baltimore.

18 Unattributed 1971 clipping in Pete Varney file, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

19 “Tourists Are Washed Out; Catcher Added to Roster,” Asheville (North Carolina) Citizen-Times, July 13, 1971: 12.

20 “Varney-Wettergreen,” Boston Globe, December 12, 1971: 201; E-mail from Pete Varney, March 20, 2019.

21 Author’s personal observations from 2005 through 2018. In 1961, 10 years before Varney played at McCormick Field, 21-year-old Willie Stargell hit 21 home runs and drove in 89 over a full season playing for Ashville, then a Pittsburgh affiliate. More recently, Brian Mundell, a 22-year-old Colorado Rockies farmhand, rapped out 41 of his 59 South-Atlantic-League-record doubles at McCormick Field in 2016. Brian Mundell 2016 splits, MiLB.com, accessed March 5, 2019.

22 Vic Roych, “Varney Surmounts First Impressions,” Arizona (Tucson) Daily Star, June 18, 1972: 25.

23 Ibid.

24 E-mail from Pete Varney, March 20, 2019.

25 Ibid.

26 AP, “White Sox Slugger Allen Is Sidelined For Season,” Allentown (Pennsylvania) Morning Call, August 26, 1973: 42.

27 Mike Klein, “Bungled Draft Choice Haunting White Sox,” Wheeling (Illinois) Herald, September 26, 1973: 29.

28 AP, “Santo says he will not play for Cubs,” Baltimore Sun, December 11, 1973: 28.

29 “ChiSox Ink Pete Varney,” Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, Mississippi), February 27, 1974: 19.

30 Bill Newell column, Hartford Courant, March 21, 1974: 77.

31 “Baseball Transactions,” Shreveport (Louisiana) Times, April 2, 1974: 9.

32 Des Moines Register, April 4, 1974: 3S.

33 Ibid, April 24, 1974: 3S.

34 The Yankees and National League New York Mets shared Shea Stadium, the Mets’ home ballpark, in 1974 and 1975 while Yankee Stadium was being renovated. David Russell, “When Mets, Yankees Called Shea Stadium Home,” Queens Gazette, August 20, 2014, qgazette.com/news, accessed December 21, 2018.

35 Bob Verdi, “Sox Game against O’s Rained Out,” Chicago Tribune, September 1, 1975: 45.

36 Ibid. Varney was remembering the Red Sox’ “impossible dream” season, in which they won their first American League pennant since 1946. They lost the 1967 World Series in seven games to the St. Louis Cardinals.

37 Unattributed June 1975 clipping in Pete Varney Hall of Fame file.

38 AP, “Sox Break Losing Streak,” Herald-Palladium (St. Joseph, Michigan) May 1, 1976: 14. During his tenure with the White Sox in 1976, Varney threw out three of 21 potential base stealers (14%). This contrasts with his better caught-stealing success with the team in 1974 (71%) and 1975 (41%).

39 Bob Verdi, “Sox Players Bitter Over Varney Trade,” Chicago Tribune, June 17, 1976: 57.

40 Kelly Dude, “Pete Varney’s Pro Career Hits Skids. From Chicago to Atlanta to Richmond,” Atlanta Constitution, July 7, 1976: 1C, 6C.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid.

43 Charles Scoggins Jr., “Major Leaguer Coaches Basketball at Littleton,” Lowell Sun (Lowell, Massachusetts), January 27, 1977: 34.

44 Ibid.

45 AP, “Red Sox Eye Finals,” News-Journal (Mansfield, Ohio), September 8, 1977: 25.

46 The Sporting News, November 19, 1977: 62.

47 “Unsigned,” Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), March 24, 1978: 21.

48 Marvin Pave, “For Football Hero, It’s the Diamond That Shines Now,” Boston Globe, April 1, 2001: 16-17.

49 E-mail from Pete Varney, March 27, 2019.

50 “Longtime Baseball Coach Announces Retirement After 34 Years,” Brandeis Alumni News.edu, posted June 26, 2015, accessed March 14, 2019.

51 E-mail from Pete Varney, March 27, 2019.

52 “Longtime Baseball Coach.”

53 Ibid.

54 E-mail from Pete Varney, March 27, 2019.

Full Name

Richard Fred Varney

Born

April 10, 1949 at Roxbury, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.