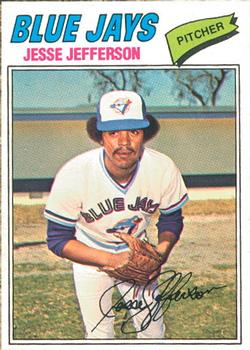

Jesse Jefferson

Jesse Jefferson’s nine-year career spent with five teams is best remembered for his being one of the original 1977 Blue Jays. Despite an overall 39-81 won-lost mark, the right-hander holds Toronto’s franchise record for hurling the most innings (12) in a complete game. When he defeated Oakland’s Mike Norris, 1-0, in 11 innings on May 16, 1980, it was the longest shutout duel between African-American pitchers in major league history.

Jesse Jefferson’s nine-year career spent with five teams is best remembered for his being one of the original 1977 Blue Jays. Despite an overall 39-81 won-lost mark, the right-hander holds Toronto’s franchise record for hurling the most innings (12) in a complete game. When he defeated Oakland’s Mike Norris, 1-0, in 11 innings on May 16, 1980, it was the longest shutout duel between African-American pitchers in major league history.

Jesse Harrison Jefferson, Jr. was born in Midlothian, Virginia, on March 3, 1949, the first of three sons born to Jesse, Sr., a Navy veteran and hospital aide, and Lillian (Holmes), a domestic worker. Fifteen miles west of Richmond, Midlothian was once a booming coal town, but that industry had declined by 1950, when about 4,400 people lived there. It has since become part of the Greater Richmond Region.

According to Jesse, Jr.’s son Ian, “The way my Dad was introduced to baseball was, my Grandfather was a pitcher as well…He played in a Negro league based here near Powhatan, Virginia.”1 Jesse, Jr. played for Little League and neighborhood teams. In 1961, however, he had to become “the father of our house, since my father died of a heart attack when I was 12.”2

In 1965, Jefferson enrolled at George Washington Carver High School. At the time, Carver was the county’s lone high school for African-Americans. “Our athletic facilities were substandard,” recalled Bernard Anderson, co-captain of the baseball team that year. “Within the environment, we did persist.”3

As a ninth-grader, Jefferson hurled a 16-strikeout no-hitter early in the season, which ended with him pitching Carver to the Central District championship in a playoff game in Richmond.4 By his junior year, pro scouts began to look at him. “I had a lot of invitations to tryouts before the accident,” he said.5

Jefferson described “the accident” as follows: “I was dozing as the passenger in a car. Well, the driver fell asleep, too. I was thrown through the windshield and suffered a fractured skull. They took 150 stitches in my forehead and over the right eye and there was a fear vision in the right eye might go.”6 He was lucky to be alive, but a significant scar remained. “All the scouts gave up on me, that is, except for the Orioles,” Jefferson continued. ”Only Baltimore’s Dick Bowie stuck around.”7

On April 12, 1968, Jefferson struck out 17 in a no-hit victory over Peabody High School to begin his senior year.8 On June 6, the Orioles chose him in the fourth round of the amateur draft. “All I wanted to do was play baseball,” he recalled.9 Two days later, scout Walter Youse signed the six-foot-three, 188-pound right-hander to his first professional contract.10 The Virginian reported to the Bluefield [WV] Orioles of the Rookie-level Appalachian League. On June 24, he whiffed 16 Marion Mets.11

Asked to describe his most interesting baseball experience on a questionnaire he filled out that summer, Jefferson replied, “The most interesting experience in baseball I’ve ever had is right now, because I have learn[ed] a whole lot about my position.”12 Soon, he’d be able to update his response to leading his team with 99 strikeouts in only 69 innings, proving his arm could compete in the pros. His 66 walks, 10 wild pitches and 3-7 record, on the other hand, indicated there was plenty of room to improve.

Following Jefferson’s off-season studies at John Tyler Community College in Chester, Virginia, the Orioles sent him to the Single-A Miami Marlins in the Florida State League in 1969. He struck out nine and allowed only one hit in seven frames, but he walked eight and was sent back to Bluefield. There, he regressed, walking 51 and uncorking 11 wild pitches in 34 innings while posting an 0-7 record and 8.21 ERA. “I had arm trouble,” he explained. “I got a cold in my arm from sleeping with my window open in West Virginia. I was off about a month that year and didn’t have time to catch up.”13

Jefferson, nicknamed “Jess” or “Jesse Jeff”, improved a little in the Florida Instructional League that fall, but made substantial progress with the Single-A Stockton [CA] Ports in 1970. Though he led the California League in losses and walks –and finished second in hit batsmen and wild pitches—he gained 157 innings of experience and tossed his first three professional shutouts. In one, a one-hitter against Modesto on August 4, the weak-hitting pitcher bounced the game-winning single into right field in the bottom of the ninth to give himself a 1-0 victory.14

The Orioles put him on their 40-man roster and invited him to spring training after another visit to the Instructional League. With roving minor league pitching instructor Herm Starrette, Jefferson worked to improve his control and temper. “Errors used to bother me,” he confessed. “Someone would boot one and I’d lose concentration. But now I realize the infielders feel the same way when I walk a hitter.”15

Promoted to Dallas-Ft. Worth of the Double-A Dixie Association in 1971, he lowered his bases-on-balls to below six per-nine-innings for the first time, and enjoyed his first winning season as a pro. In assessing the circuit’s hurlers that season, Amarillo’s Jake Brown remarked, “Jesse Jefferson…has given me the most trouble of any pitcher I have faced so far. He seems to be the hardest thrower.”16

Jefferson returned to Double-A in 1972 and pitched the opener for Baltimore’s new Southern League affiliate, the Asheville [NC] Orioles.17 After going 5-4 with a 3.30 ERA in 11 starts, he earned a promotion to the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings, where he became even more effective. In defeating Syracuse with consecutive complete games in mid-July, Jefferson held the Chiefs to a total of three hits.18 In 103 innings, he permitted only 79 hits and went 6-3 with a 2.45 ERA.

Next, he spent the winter in the Venezuelan League with a club managed by Orioles first base coach Jim Frey. For the Tigres de Aragua, Jefferson cut his walks to 30 in 79 innings.19 “I learned a lot playing winter ball and I picked up the slider as my fourth pitch to go along with the fastball, curve and changeup,” he reported.20

The rise of Jefferson, fellow right-hander Wayne Garland, and lefty Don Hood allowed the Orioles to trade two pitchers to the Braves in a six-player deal for slugging catcher Earl Williams that winter. The trio of youngsters began the 1973 season at Rochester, but Baltimore skipper Earl Weaver said he nearly kept Jefferson on his Opening Day roster. “The only reason we sent him out was because we wanted him to pitch regularly,” the manager explained. “If he harnesses that ability, he’ll be pitching similar to Jim Palmer and Chicago’s Fergie Jenkins,” the skipper predicted. 21

“Earl gave me a lot of confidence when he told me what he thought of my pitching and told me to go back, have a good year, and he would call up the one doing the best job when he needed someone,” Jefferson said.22 By June 9, Jefferson had a 6-2 record for the Red Wings after beating Peninsula in what he called his best game of the year. “Instead of using a slider early in the game, I held it back until the fifth or sixth,” he explained. “Then, when they started looking for the curve, I came in with the slider.”23 Two nights later in Syracuse, he pitched an inning for the International League All-Stars and struck out two Montreal Expos.24 On June 15, the Orioles sold Orlando Pena to the Cardinals and summoned Jefferson to the majors. “[Red Wings manager Joe] Altobelli called me into his office,” he recalled. “Carl Steinfelt, the general manager, was there too and they told me the Orioles wanted me to report to Baltimore. I was happy, but I’ve got to prove myself.”25

Jefferson’s major league debut was outstanding. On June 23, in front of 30,676 at Fenway Park, he came within one pitch of shutting out the Red Sox, 1-0, before Rico Petrocelli homered to tie the score. Instead, he pitched 10 innings and won, 2-1. “Jesse will get his share of starts from now on,” proclaimed Weaver.26

When Doyle Alexander went on the disabled list with a sore elbow, Jefferson replaced him in the rotation. On July 30, he started a nationally televised Monday Night Baseball contest against Detroit. Three Tigers took him deep, however, as NBC’s Tony Kubek correctly predicted the rookie’s pitches from the broadcast booth.27 “Tip-offs were his problem,” confirmed Baltimore pitching coach George Bamberger. “You could see them sitting on the sidelines.”28

When a curve was coming, hitters noticed an extra hesitation in Jefferson’s exaggerated pumping motion and a telltale wiggle of his glove as he grasped the ball. On fastballs, they could see more of the baseball when he gripped it, and his overhand arm speed was another giveaway.29 He adjusted and struck out nine Red Sox in his next start to lift the Orioles into first place. As Baltimore closed in on the division title in September, he beat Detroit twice, one a complete-game win over Mickey Lolich at Tiger Stadium.

Following a 6-5, 4.11 ERA rookie season, Jefferson kept working in the Instructional League. “We have firmed up his wrist and have Jesse pitching more from out of the glove down near his waist,” Bamberger explained. “We’ve developed a more compact motion with the left shoulder down lower and tucked in.”30

Baltimore traded for southpaw Ross Grimsley in December, however and the rotation already featured four-time 20-game winner Dave McNally and two former Cy Young Award winners. “Earl Weaver was the type of manager who let me know I had to wait my turn behind Jim Palmer, Mike Cuellar, and the other starters,” Jefferson explained.31 Garland and Hood had also reached the majors by the end of 1973, and the Orioles didn’t have room for all of them in 1974. Jefferson told GM Frank Cashen that he’d rather be traded than return to Rochester.32

He spent the entire year in the big leagues but made only 20 appearances, 18 out of the bullpen. “It was the first time I had been in relief, but that’s all they could do with me since they had such a fine staff,” Jefferson said.33 He won his only decision of the season on the Fourth of July, beating Luis Tiant at Fenway Park in a rare start. He did not pitch in the playoffs for the second straight year as the Orioles fell to Oakland again.

In 1975 he received even fewer chances, pitching four times in Baltimore’s first 56 games before he was traded to the White Sox for first baseman Tony Muser. “Although I have a lot to thank the Orioles for, and will always be grateful to them, I’m glad to be here,” Jefferson said upon arriving in Chicago.”34

The AL West’s last-place team was happy to have him. “Outside of Jim Palmer, he had the best arm on the Baltimore staff,” raved White Sox manager Chuck Tanner.35 On June 22 at Comiskey Park, Jefferson carried a no-hitter into the sixth inning in his debut and beat the Twins. Pitching coach Johnny Sain helped him develop a sharp curveball, and he started 21 games by season’s end.

“No one here has bugged me about my control,” Jefferson remarked after joining his new team.36 For years, he’d resisted being labelled a wild pitcher. “I don’t have control problems,” he insisted. “I can concentrate on each pitch, so I know where I’m going to throw the ball. But even in batting practice, I’ll throw a couple of good strikes, then two balls, then they’ll say I’m wild.”37 By the end of 1975, however, his 5-9 record with a 5.10 ERA for Chicago included an unacceptably high total of 94 walks in 107 ⅓ innings.

After winter ball with the Santurce Crabbers in Puerto Rico, Jefferson met the new White Sox manager, 67-year-old Paul Richards. Upon eyeing what one reporter described as Jefferson’s “octopus-like windup,” Richards remarked, “I dunno. He looks a little goofy to me.”38 Once the season started, Jefferson didn’t throw a single pitch in any of the first 24 games. “It’s bad being the only man on the team who hasn’t played at all,” he said. “I don’t know whether Richards likes me or not. If I asked him why I haven’t pitched, he might think I have a bad attitude. I don’t want to get that reputation because I never had it with any club.”

“I’ve been working out by myself, throwing the ball against the brick wall in centerfield at home, pickoff moves and everything,” Jefferson explained. “If you give up on yourself in this game, nobody else cares.”39

When Jefferson finally made his season debut on May 17, he walked eight. Five days later, however, he didn’t issue a single base on balls in seven innings against the A’s, something he’d never done before. “Paul made one change in my delivery,” he explained. “Rather than bringing my hands to the back of my head, I now bring them together at the bill of my cap. My arm is ahead of my body now instead of the other way around. Control is better. The man is a genius.”40

Jefferson married Faye Hicks shortly after the All-Star break, but he won only once more and appeared in just seven of Chicago’s last 69 games, working only 14 ⅔ innings. “I was really down,” he confessed. “But I talked it over with my wife, Faye, and we decided that I’d try to hold on as well as I could.”41 By the end of the season, his ERA had ballooned to 8.52. When he looked back on the ordeal the following summer, he confessed, “My mind was really screwed up.”42

He returned to the Tigres de Aragua and went 8-6 with a 3.49 ERA in 15 starts. “I had a successful season in the Venezuelan Winter League and got my confidence back,” he said.43 While Jefferson was in South America, the Toronto Blue Jays selected him in the expansion draft. During the summer of 1977, he’d remark, “I prayed to get over here. Coming to an expansion club was the best thing that ever happened to me.”44

Jefferson established career highs in starts, innings and strikeouts while going 9-17 with a 4.31 ERA for a Toronto team that finished a major league worst 54-107. In his best outing, on June 8, he nearly beat Nolan Ryan, 1-0, in Anaheim before allowing a game-tying single with two outs in the ninth. He won three straight starts in late May, pitched five complete games in one six-start stretch, and walked only 3.4 batters per-nine-innings. In a 2-1 loss at Detroit, he went the distance without issuing a single base on balls for the first time in the majors. “Jesse is starting to show signs of putting it all together,” observed Blue Jays’ manager Roy Hartsfield.45

In 1978, Jefferson tossed his first two major league shutouts –both three-hitters against Chicago. “Bill Veeck is a super guy. I don’t have anything against the White Sox,” he insisted. “I just didn’t get to pitch over there.”46 After the first one, Toronto pitching coach Bob Miller said, “In the past, when he got behind, he had to go to his fast ball, but now that his slider is so good, he can use it any time. All he has to do is take a little speed off, put a little money on, keep the batters off stride.”47

Toronto finished last again, but Jefferson threw a career-high nine complete games and led the pitching staff in innings. When he beat the Red Sox, 2-1, on May 23, he worked all 12 innings, still the longest complete-game effort in Blue Jays history.48 Ten days later, he threw only 93 pitches in going the distance against the Rangers. “Here it’s beautiful. There’s no pressure on me,” he said. “They give me the ball and tell me to go as hard as I can for as long as I can.”49

Hartsfield had other plans in 1979, though. He wanted Jefferson to become his short-relief ace. “I place more importance on finishing than starting,” the manager explained.50 Jefferson, who notoriously threw up to 100 pitches in the bullpen before a start, said, “It’s kind of a surprise. The big thing I see is learning to get loose in a hurry.”51

By May 1, the experiment was abandoned, and Jefferson was back in the rotation, but he won only once in 10 starts and went back to the pen. One of his defeats was a 1-0 heartbreaker to the Red Sox on May 27 in which he pitched nine innings without issuing a walk for the only time in his career. His teammates supported him with more than three runs only twice, but his 2-10 record and 5.51 ERA were poor from any perspective. The Blue Jays lost 109 games, still the worst season in franchise history through 2020.

In 1980, Toronto finally avoided 100 defeats for the first time, and Jefferson began the season as new manager Bobby Mattick’s fifth starter. The right-hander was encouraged to abandon his slow curve.52 During spring training, incoming pitching coach Al Widmar insisted that he looked like a different pitcher.53

Nevertheless, Jefferson was only 1-1 with a 6.05 ERA when he went head-to-head with Oakland’s Mike Norris on May 16 at Exhibition Stadium. Norris entered the matchup with a 5-0 record and major-league best 0.36 ERA. The right-handers matched zeroes through nine innings, then 10. After Jefferson hurled a scoreless top of the 11th as well, he’d retired 13 of the last 14 hitters since stranding two runners in scoring position in the sixth. He’d struck out a career-high 10. “Later in the game, after finishing an inning, he’d look into our dugout at me with this cool little smile.” Norris recalled. “Jesse was a superstar that night.”54

It was the longest shutout duel in major-league history between two African-American pitchers. After the Blue Jays prevailed on Roy Howell’s two-out single in the bottom of the 11th, Norris threw a fit in the visitors’ locker room before calling Jefferson to congratulate him.55

Jefferson didn’t win again for more than two months. After he shut out the Mariners on two singles on July 27, Mattick remarked, “Behind Jim Clancy and Dave Stieb, he has the best stuff on the team. If he would just keep within himself the way he did today.”56

After an 0-6 August dropped Jefferson’s record to 4-13, however, the Blue Jays put him on waivers in September. “He can make you cry sometimes, but at times he can give you a superb performance,” remarked Mattick. Toronto GM Pat Gillick said, “He hasn’t shown any improvement since he’s been with us. Maybe a change of scenery will be best for Jesse.”

The Pirates claimed Jefferson, and he won his only start for Pittsburgh on the season’s final weekend. He then became a free agent, but only the Mariners selected him in the reentry draft, allowing him to negotiate with all teams.57 He signed with the Angels shortly before spring training and began 1981 in California’s rotation, but spent most of the strike-shortened season in long relief. Despite a serviceable 3.92 ERA, the Angels let him go and he never pitched in the majors again. He finished his career with a 39-81 record and 4.81 ERA in 237 games, including 144 starts.

Jefferson returned to the Baltimore organization just before spring training in 1982, expecting to begin the year in Triple-A. “I had an offer to play in Mexico, but I’d rather go to Rochester,” he said.58 After the Orioles released him before Opening Day, he wound up in Mexico after all. On July 7, he pitched a seven-inning no-hitter for the Nuevo Laredo Owls.

In August 1983, when a Toronto reporter traveled nearly 1,700 miles west to write about one of Canada’s Pacific Coast League teams, he was surprised to find the graying, 34-year-old ex-Blue Jay in an Edmonton Trappers uniform. “Just got called up from the Mexican League,” Jefferson told him. “I was there for the last two years, and it wasn’t a good feeling.”59 He added that he hoped to make it back to the majors but, after posting a 5.40 ERA in three appearances for the Triple-A club, his professional baseball career was over. In December, his marriage ended, too, after seven-and-a-half years and three sons: Tommy, Corey and Ian. He also fathered a daughter, Kim.

Jefferson returned to Midlothian. Early in his career, he’d told a reporter, “When I do go home, my favorite hobby, outside of baseball, is hunting deer. And if I can get in a little fishing, that’s about all I do.”60 To pay the bills, he drove a collection truck for Waste Management, “which he enjoyed doing,” noted his son, Ian.

On September 8, 2011, Jefferson died from prostate cancer. He was 62. He was buried at the First Baptist Church Cemetery in Midlothian.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Faye Hicks, Ian Jefferson and Tommy Jefferson for their help filling in blanks and encouraging support.

This biography was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com and www.retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Ian Jefferson, E-mail to author, October 19, 2020.

2 Jim Elliot, “Jefferson in Bird Debut Tonight,” Baltimore Sun, June 22, 1973: C10.

3 Rich Griset, “Before Desegregation, Carver Principal Was ‘Strong Man Among Men,” https://www.chesterfieldobserver.com/articles/before-desegregation-carver-principal-was-a-strong-man-among-men/ (last accessed October 24, 2020).

4 Guest Book message from 1965 Carver Baseball Co-captain Bernard Anderson in “Jesse H. Jefferson, Jr.,” https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/timesdispatch/name/jesse-h-jefferson-obituary?n=jesse-h-jefferson&pid=153539631&fhid=3610 (last accessed October 21, 2020).

5 Seymour S. Smith, “Only Birds Sought Hurler After Accident,” Baltimore Sun, June 29, 1971: C2.

6 Smith, “Only Birds Sought Hurler After Accident.”

7 Smith, “Only Birds Sought Hurler After Accident.”

8 “Carver Nips Peabody, 1-0,” Norfolk Journal and Guide, April 13, 1968: 12.

9 Unger, “Sox, Jesse Jefferson Good for Each Other.”

10 1975 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 72.

11 “Rookie Leagues,” The Sporting News, July 13, 1968: 49.

12 Jesse Jefferson’s August 14, 1968 Baseball Questionnaire.

13 Larry Bump, “Jesse’s Shooting for Top,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), March 20, 1973: 35.

14 “Ends Super Slump,” The Sporting News, August 22, 1970: 45.

15 Smith, “Only Birds Sought Hurler After Accident.”

16 Putt Powell, “Brother’s Advice Helped Brown,” Amarillo Globe-Times, June 1, 1971: 10.

17 Harry Lloyd, “Southern Starts with Rivals’ Rematch,” The Sporting News, April 29, 1972: 30.

18 “Encore for Jesse,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1972: 38.

19 http://www.pelotabinaria.com.ve/beisbol/mostrar.php?ID=jeffjes001 (last accessed October 19, 2020).

20 Bump, “Jesse’s Shooting for Top.”

21 Elliot, “Jefferson in Bird Debut Tonight.”

22 Elliot,

23 “Lemanczyk Able Hen,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1973: 40.

24 Bill Reddy, “Rookie-Led Stars Play Montreal at Syracuse,” The Sporting News, June 23, 1973: 36.

25 Elliot, “Jefferson in Bird Debut Tonight.”

26 Lou Hatter, “Blair Regains Star Route with Aid of Hypnotist,” The Sporting News, July 14, 1973: 21.

27 Lou Hatter, “Jefferson Stops Tipping Off Batters,” Baltimore Sun, April 5, 1974: B12.

28 Hatter, “Jefferson Stops Tipping Off Batters.”

29 Hatter

30 Hatter,

31 Bob Logan, “Jefferson Losing Patience with Sox,” Chicago Tribune, May 13, 1976: C1.

32 Doug Brown, “Orioles May Flash ‘No Vacancy’ Sign for Two Rookie Pitchers,” Baltimore Sun, March 23, 1974: 50.

33 Norman O. Unger, “Sox, Jesse Jefferson Good for Each Other,” Chicago Defender, July 1, 1975: 24.

34 Unger, “Sox, Jesse Jefferson Good for Each Other.”

35 Richard Dozer, “Chisox Staff Takes Heavy Portside List,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1975: 17.

36 Richard Dozer, “Johnson Slugging Way into Hearts of White Sox,” The Sporting News, July 12, 1975: 10.

37 Bump, “Jesse’s Shooting for Top.”

38 Dave Nightingale, “Jays’ Jefferson Not So ‘Goofy’ in Three-Hitter,” Chicago Tribune, April 24, 1978: E1.

39 Logan, “Jefferson Losing Patience with Sox,”

40 Bob Verdi, “Dr. Richards Works Miracles Rehabilitating Sox Pitchers,” Chicago Tribune, May 30,1976: B1.

41 Nightingale, “Jays’ Jefferson Not So ‘Goofy’ in Three-Hitter.”

42 Bill Madden, “Jefferson Finally Helping the Chisox,” Raleigh Register (Beckley, West Virginia), August 10, 1977: 25.

43 Nightingale, “Jays’ Jefferson Not So ‘Goofy’ in Three-Hitter.”

44 Madden, “Jefferson Finally Helping the Chisox.”

45 Neil MacCarl, “Jays’ Jefferson Thrives on Heavy Duty,” The Sporting News, August 6, 1977: 10.

46 Madden, “Jefferson Finally Helping the Chisox.”

47 Paul Patton, “Jesse Jeffwrson Stops Chisox with 3-hit Shutout,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), April 24, 1978: S1.

48 On May 17, 1980, Toronto’s Dave Stieb pitched the first 12 innings of a 14-inning game, https://www.mlb.com/bluejays/history/records-stats-awards/single-game-records (last accessed October 24, 2020).

49 Nightingale, “Jays’ Jefferson Not So ‘Goofy’ in Three-Hitter.”

50 Neil MacCarl, “Jays Tap Jefferson as Key Reliever,” The Sporting News, March 24, 1979: 48.

51 MacCarl, “Jays Tap Jefferson as Key Reliever.”

52 Neil MacCarl, “Jefferson Surfaces on Jays Hill,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1980: 35.

53 Neil MacCarl, “Outlook Gray for Blue Jays,” The Sporting News, April 12, 1980: 36.

54 Dave Jordan, “Norris (5-0) vs. Jefferson (1-1),” https://tht.fangraphs.com/norris-5-0-vs-jefferson-1-1/ (last accessed October 19, 2020).

55 James Golla “Deadline Nears, Look for Deals,” Globe and Mail, May 24, 1980: S7.

56 MacCarl, “Jefferson Surfaces on Jays Hill.”

57 Jack Lang, “Surprises in Draft,” The Sporting News, November 29, 1980: 51. If a player was selected by two or fewer teams, he became a free agent.

58 “Overheard Around Camp,” Democrat and Chronicle, March 25, 1982: 35.

59 Marty York, “Trappers a Big Hit,” Globe and Mail, August 30, 1983: 49.

60 Unger, “Sox, Jesse Jefferson Good for Each Other.”

Full Name

Jesse Harrison Jefferson

Born

March 3, 1949 at Midlothian, VA (USA)

Died

September 8, 2011 at Midlothian, VA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.