Phil Garner

What does Phil Garner have in common with Sir Edmund Hillary and Neil Armstrong?

The answer is that all three performed feats never before achieved by humankind. Sir Edmund was the first person to reach the summit of Mount Everest. Neil Armstrong was the first person to set foot on the moon. And Phil Garner boldly went where no Houston Astros manager had gone before when he led the team to its first World Series appearance in 2005.

Of course, that was not the only achievement of Garner’s baseball career, but certainly one of the most significant in a career that included a World Series ring and three All-Star appearances in a 16-year playing career.

Philip Mason Garner was born on April 30, 1949, in Jefferson City, Tennessee, to Drew and Mary Francis (Helton) Garner. Both his father and grandfather were Baptist ministers. He grew up in Rutledge, Tennessee, 15 miles from Jefferson City. As a teenager, he went to Bearden High School in Knoxville due to the quality of the school’s athletics and, upon graduating, accepted a baseball scholarship at the University of Tennessee.

Garner had a successful career as a Volunteer, both academically and athletically. He was twice named All-Southeast Conference and led the NCAA in 1969 with a 0.36 home runs per game average, based on 12 homers in 33 games. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in business.

The Montreal Expos drafted Garner in the eighth round of the 1970 amateur draft. The Expos showed minimal interest in their pick, so he didn’t sign with them and became available in the January 1971 secondary draft. This time the Oakland A’s, a dynasty in the making, scooped up the third baseman in the first round (third overall), signed him, and sent him to their A-ball affiliate, the Burlington (Iowa) Bees in the Midwest League.

Garner made a seamless transition from college ball to the pros. In 116 games, he hit .278, smacked 11 home runs, and drove in 70 runs. On the defensive side, the hot corner was proving to be a bit too toasty, as he committed 29 errors and had a .918 fielding percentage.

Garner married his wife, Carol, in 1971. They went on to have three children, sons Eric and Ty, and daughter Bethany.

Garner’s fine 1971 season earned him a promotion for 1972 to the Birmingham A’s in the Double-A Southern League, where he continued battering opposition pitching despite being on a bad (49-90, 29 GB) team. In 71 games, Garner hit .280, with 12 homers and 40 RBIs. These numbers earned him a midseason trip back to Iowa, this time with the Triple-A Iowa Oaks of the American Association. He had more difficulty hitting at this level, as his .243 average in 70 games will attest. He hit nine home runs and had 22 RBIs. Defensively, Garner had better statistics at Triple-A than he did at Double-A. Handling virtually the same number of chances at each level, he had fewer errors at Triple-A.

The poorer offensive numbers at Iowa convinced Athletics management that Garner needed more seasoning, and they sent him to their new Triple-A affiliate, the Tucson Toros of the Pacific Coast League, in 1973. That season, he batted .289 with 14 home runs and 73 RBIs, but committed 35 errors and had a .913 fielding percentage. Defensive numbers notwithstanding, Garner received a September call-up to the A’s, who were on their way to repeating as World Series champions. He appeared in nine games for Oakland, and went 0-for-5 at the plate with three strikeouts.

With Sal Bando as the team’s regular third baseman, the A’s weren’t in any hurry to bring Garner up, so he returned to Tucson for another season in 1974. That season turned out to be frustrating for Garner. He was doing well in Tucson; he hit .330 in 96 games. However, in two stints with the parent club, he got into only 30 games, mainly as a defensive replacement. He hit a meager .179 in 28 at-bats and spent a lot of time on the bench.

With an incumbent at third and poor statistics to show for his time in the majors, Garner didn’t have a lot to be optimistic about as spring training 1975 rolled around. Then, on March 6, 1975, the A’s cut longtime second baseman Dick Green from their roster and Garner, who hadn’t played second base since his university days five years earlier, was slotted into the position.

“I haven’t seen anything look tough for him in the drills,” said A’s manager Alvin Dark. “We’ll just have to see what happens when the buffaloes come toward him at second base.”1

As it happened, Garner handled the buffaloes and any other wildlife that came his way quite well. By midseason it was clear that he could not only make the plays around second base, but that he was also a much better hitter than Green.

“I thought Phil would have trouble at the beginning of the season but he didn’t,” said Bando. “He’s aggressive at the plate and in the field. He’s a good ballplayer — a good, gutty ballplayer.”2

The “good, gutty ballplayer” helped the A’s overcome the loss of staff ace Catfish Hunter and win a fifth consecutive American League West title. Overall, Garner hit .246 with six home runs and 30 RBIs. Despite the plaudits he was receiving, he still had to improve on defense, as he led the league in errors with 26.

By 1976 A’s owner Charlie Finley was in full dismantle mode as he began getting rid of the players from his dynasty teams. He traded Reggie Jackson, Ken Holtzman, and minor leaguer Bill VanBommell to Baltimore for Don Baylor, Mike Torrez, and Paul Mitchell. The A’s nonetheless remained competitive, finishing in second place in the AL West with an 87-74 record under new manager Chuck Tanner. Garner’s offensive numbers improved; he hit .261, with eight home runs and 74 runs batted in. He also displayed good speed by stealing 35 bases. His defense was a little better, as he cut his errors to 22, but that was still second-highest in the leagues. Overall, Garner played well enough to be selected to the American League All-Star team.

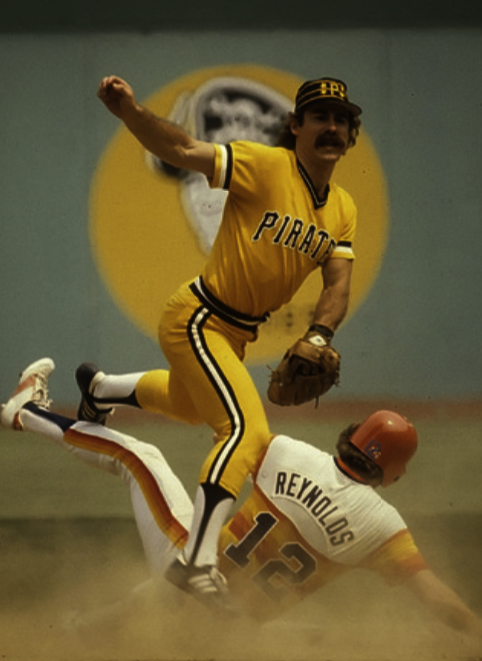

Finley continued divesting the A’s of their good players prior to the 1977 season. Garner was fortunate to be one of them, as he was part of a trade that saw him go to the Pittsburgh Pirates with Chris Batton and Tommy Helms for Tony Armas, Doug Bair, Dave Giusti, Rick Langford, Doc Medich, and Mitchell Page. Garner contributed to the 96-66 Bucs, now led by Tanner, instead of languishing with the 63-98 A’s. His numbers were similar to those of the previous season. He hit .260, showed more power with 17 home runs, drove in 77 runs, and stole 32 bases. He also showed flexibility on defense, for while he played primarily at third base (107 games), he also saw action at second base (50 games) and shortstop (12 games). None of his defensive statistics, good or bad, were among the league leaders.

Garner’s offensive numbers dipped slightly in 1978. He hit .261, but his home runs (10), RBIs (66), and stolen bases (27) were all down from the previous season, although he had a career-high .441 slugging percentage. Two of those home runs made baseball history.

On September 14 Garner hit a grand slam, the first of his major-league career, in a 7-4 Pirate win over the St. Louis Cardinals. Having quickly acquired a taste for grand salami, he hit another one the very next night in a 6-1 win over the Montreal Expos. It marked only the second time in National League history, and the eighth time in major-league history, that a player hit grand slams in consecutive games. The only previous National Leaguer to do it was James Sheckard of the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1901.

“I feel good I did it,” Garner said after the second one, “but I wasn’t trying to do that … when I went up there. At the time I was just glad we got a four-run lead out of it.”3

Defensively, Garner split his time primarily between second and third, playing at each position in 81 games (as well as playing shortstop in four games). Perhaps the shifting of positions hurt his defense, because he ended up fourth in the league in total errors committed, with 28. Garry Templeton of the Cardinals led the league with 40.

Even Pittsburghers who hate disco love the song “We Are Family” — the anthem of the 1979 Pirates that rode the team’s atmosphere and Willie Stargell’s leadership to a World Series victory over the Baltimore Orioles.

Garner had arrived in Oakland too late to participate in any of the A’s’ ring ceremonies, but he played an important role in Pittsburgh’s drive to the title. He had career highs in batting average (.293), hits (161), and on-base percentage (.359), and tied his career high in slugging (.441).

Garner also performed well under playoff pressure. He got five hits in 12 at-bats in the National League Championship Series with a triple, a home run, an RBI, and four runs scored. He batted .500 in the World Series with 12 hits in 24 at-bats, five RBIs, and four runs scored.

An Associated Press article on Garner just before the 1979 season illustrated what kind of ballplayer he was.

(The Pirates) took Garner, an All-Star second baseman in the American League and stationed him at third. But since then, because of various injuries, Garner has played third, shortstop and second base for the Pirates. He figures the switching does have a little effect on his overall performance, but dismisses (the effects) by saying it’s the mark of a professional to adjust.4

Somebody in Pirates management must have agreed with the article, because the team allowed incumbent second baseman Rennie Stennett to leave via free agency after the 1979 season and handed Garner the keys to the keystone sack. In 1980 Garner played in 151 games at second base and responded with another All-Star season. His batting average dropped to .259 and his home run total dropped to five, but he drove in 58 runs and stole 32 bases. Despite not having to make the adjustments that come with switching positions, he led the National League in errors by a second basemen with 21, although he also led the league in assists (499) and double plays turned (116) at his position. He had a hit, scored a run, and stole a base in the All-Star Game as well.

Garner’s 1981 season was an odd one. His offensive numbers dropped significantly that season, yet he made the All-Star team again. He also found himself with a new team; the Pirates traded him to Houston as he was about to become a free agent and contract negotiations with the Pirates were proving fruitless. Shoulder surgery in April 1981 had also hampered Garner defensively.

The Astros desperately needed help at second base. Incumbent Joe Morgan was injured, and the team had had more auditions than a Broadway chorus for an adequate replacement. Garner arrived on August 31, just in time to qualify for the Astros’ post-season roster, in return for Johnny Ray and two players to be named later.

For the year, Garner hit only .248, with one home run and 26 RBIs. In the National League Division Series loss to Los Angeles, he had two singles in 18 at-bats.

Astros general manager Al Rosen was determined to sign Garner after the 1981 season and he succeeded, getting Garner’s signature on a three-year, $1.85 million contract, plus a club option. Perhaps having the security of a contract helped Garner relax, because in 1982 he rebounded from his poor 1981 numbers. Playing primarily at second base, he hit .274 with 13 home runs and a career-high 83 RBIs. He stole 24 bases.

An oddity of his 1982 season was his performance against the Pirates. The Astros won nine of 12 games against the Bucs, and while Garner batted only .191, he made those hits count, by driving in 11 runs and having two game-winning hits.

The 1983 Astros overcame a 0-9 start to remain competitive in the National League West, finishing in third place with an 85-77 record, six games behind division champion Los Angeles. According to Garner, the team never let adversity stop them.

“These guys just don’t face reality,” Garner said. “When we were 0-9, these guys weren’t thinking whether we would ever win a game. Everybody felt like we were fixing to run off a string of wins at any time.”5

Garner’s batting average for the year had fallen to .238, but he still had good production with 14 home runs and 79 RBIs. And while the hits didn’t keep on coming, the errors did. Having returned to third base because incumbent Art Howe was out all season due to injury, Garner finished second in errors among National Leaguers at the position with 24.

It’s hard to say whether Garner felt as if he was living in George Orwell’s 1984 during the 1984 season, but he definitely wasn’t happy. The scrappy player, who had earned the nickname Scrap Iron for being a tough, gritty, sometimes brawling ballplayer, spent the 1984 season either on the bench or platooning at third base with Denny Walling.

“You remember Phil Garner,” wrote Bob Hertzel in the Pittsburgh Press. “‘Scrap Iron’ they called him when he was here (Pittsburgh). In Houston, though, it’s been more like ‘Scrap Heap.’”6

He wanted to be traded but wasn’t, and spent the entire season in Houston. It didn’t help that team owner John McMullen said that other teams weren’t “beating the doors down to get Phil Garner.”7

Not surprisingly, Garner’s production fell as a result. His batting average was a respectable .278, in 128 games, but he hit only four home runs and had 45 RBIs.

Considering Garner’s subpar numbers and what McMullen said, it’s surprising that the Astros exercised their option on him for 1985, but they did. Originally the plan was to have Garner and Walling platoon again, but Walling got off to a blazing start, batting .382 in April and finishing the month with an 11-game hitting streak. Walling therefore was moved to first base and Garner became the everyday third baseman for all or part of 123 Astros games that year. At the plate he hit .268, with six home runs and 51 runs batted in. No longer the speedster he once was, he stole only four bases and was caught stealing four times.

During the 1986 season, Garner achieved a personal milestone and the Astros had a highly successful season. On June 14 he not only hit his 100th career home run, but he did it in style, belting a grand slam that proved the difference in a 7-3 victory over the Giants. It was his first grand slam since the back-to-back clouts in 1978. The achievement was a bright spot in a campaign in which Garner was reduced to a part-time role, playing in only 107 games, many of them as a pinch-hitter. In 347 at-bats (his lowest total since the strike-shortened 1981 season), he hit .265 with nine homers and 41 runs batted in. His 37-year-old legs managed to steal 12 bases as Astros manager Hal Lanier brought the speed game to the team’s offense. That approach helped the Astros go 96-66 and win the National League West crown.

Houston played the New York Mets, a team that won 108 games, in the National League Championship Series, and put up a mighty struggle before losing the series in six games. Garner had two hits in nine at-bats during the series, with a double and two RBIs.

Garner’s career wound down in 1987 and 1988. He was traded from the Astros to the Los Angeles Dodgers on June 19, 1987, and was a part-time player for both teams, hitting .206 for the season with five home runs and 23 RBIs. He signed with the San Francisco Giants for 1988 and although he didn’t play much, he did live up to his Scrap Iron nickname. After having back surgery in April to repair two discs, he was able to come back when the Giants expanded their roster in September. He played his last game October 2, 1988, and got a base on balls as a pinch-hitter. It almost seems appropriate that Garner’s last out came when he tried to steal second.

Garner wasn’t unemployed very long. Art Howe hired him as a first-base coach when Howe became Astros manager for the 1989 season, and he stayed with the team for three years. He got his first managerial post with the Milwaukee Brewers in 1992 and guided them to a 92-70 record, four games behind the eventual world champion Toronto Blue Jays. Garner remained Brewers manager until August 1999, but never again achieved the same level of success that he had that first season. In fact, his Milwaukee teams never played .500 baseball after 1992. In eight years, his overall record was 563-617 (.477).

Garner took the helm of the Tigers in 2000, and after two losing seasons, he was fired six games into the 2002 campaign. His record in Detroit was 145-185 (.439).

In July 2004 Garner replaced Jimy Williams as manager of the Astros. Houston was only a .500 team under Williams at 44-44, but the team responded well under Garner, going 48-26 the rest of the way and finishing second in the NL Central with a 92-70 record, 13 games behind St. Louis. A seven-game winning streak to close out the regular season proved a harbinger of things to come. The Astros made the NL playoffs as the wild-card team, and after defeating the Braves in five games in the NLDS, they took the NLCS to seven games before losing to the Cardinals.

In July 2004 Garner replaced Jimy Williams as manager of the Astros. Houston was only a .500 team under Williams at 44-44, but the team responded well under Garner, going 48-26 the rest of the way and finishing second in the NL Central with a 92-70 record, 13 games behind St. Louis. A seven-game winning streak to close out the regular season proved a harbinger of things to come. The Astros made the NL playoffs as the wild-card team, and after defeating the Braves in five games in the NLDS, they took the NLCS to seven games before losing to the Cardinals.

The Astros repeated as the National League wild-card team in 2005 with an 89-73 record. It was déjà vu all over again as they defeated the Braves three games to one in the NLDS, and once again faced the Cardinals, who had won 100 games, in the NLCS. This time they were not to be denied as Roy Oswalt, the series MVP, pitched seven strong innings in Game Six, leading the Astros to a 5-1 win and the franchise’s first-ever trip to the World Series.

Unfortunately for Garner and the Astros, they were victims of destiny. Their opponents in the Series that year were the Chicago White Sox, who last appeared in the fall classic in 1959, three years before the Houston franchise had even played one game. The White Sox swept the Astros in four straight, to win their first championship since the doughboys went to fight in World War I in 1917.

After an 82-80 record in 2006, the Astros fired Garner during the 2007 season after he compiled a 58-73 record in 131 games. Garner then entered the oil and gas business before coming full circle and joining his first team, the Oakland A’s, as a special adviser in 2011.

No scrap heap for Scrap Iron.

Last revised: July 1, 2015

This article originally appeared in “Mustaches and Mayhem: Charlie O’s Three Time Champions: The Oakland Athletics: 1972-74″ (SABR, 2015), edited by Chip Greene. It also appears in “When Pops Led the Family: The 1979 Pitttsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Gregory H. Wolf.

Sources

Baseball-reference.com

fs.ncaa.org

mapquest.ca

news.google.com

paperofrecord.hypernet.ca.

Notes

1 Ron Bergman, “A’s Ticket Greenhorn Gardner for Green’s Job,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1975.

2 Bergman, “Garner Gleans ‘Green’ Laurels as A’s Rookie,” The Sporting News, July 26, 1975.

3 “Garner Makes Record Books,” Frederick (Oklahoma) Daily Leader, September 17, 1978.

4 Associated Press, “Garner, Parker Keep Bucs On Their Toes,” Reading (Pennsylvania) Eagle, April 4, 1979.

5 Associated Press, “Astros still fighting for pennant,” Bonham (Texas) Daily Favorite, September 15, 1983.

6 Bob Hertzel, “Like old times as Garner comes through at Three Rivers,” Pittsburgh Press, August 20, 1984.

7 Ibid.

Full Name

Philip Mason Garner

Born

April 30, 1949 at Jefferson City, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.