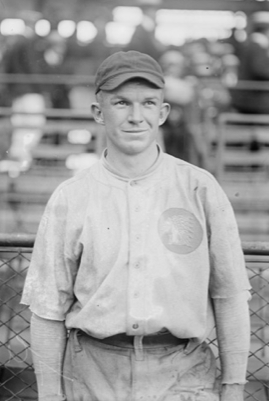

Red Smith

A mediocre fielder at third base, Red Smith was a good enough hitter to hold down third base for the Brooklyn Dodgers, until he clashed with his new manager, Wilbert Robinson. Robbie regarded Smith as a troublemaker, and Smith was summarily shipped to the Boston Braves – in time to make an important contribution as the Braves won the National League pennant, and then spend five more years with the team.

A mediocre fielder at third base, Red Smith was a good enough hitter to hold down third base for the Brooklyn Dodgers, until he clashed with his new manager, Wilbert Robinson. Robbie regarded Smith as a troublemaker, and Smith was summarily shipped to the Boston Braves – in time to make an important contribution as the Braves won the National League pennant, and then spend five more years with the team.

James Carlisle Smith was born on April 6, 1890, in Greenville, South Carolina, the second of four children of Ellen Bramlett and James Benjamin Smith, a railway postal clerk. His family moved to Atlanta when he was a child, and he called the Georgia capital home for the rest of his life. Outside of baseball he was known as Carlisle, but his baseball teammates and fans called him Red in homage to the color of his hair.

A hard hitter in college, Smith almost forsook baseball for a career in engineering. He attended a military prep school and played baseball and football at Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University) in 1908 and 1909. The latter year was a very busy one for the young man. In the spring he was a hard-hitting outfielder for the Auburn baseball team. During the early part of the summer he played for the Georgia Railway and Electric Company semipro team. Later he made his professional debut as a 19-year-old third baseman for the Anderson Electricians in the Class D Carolina Association, appearing in 48 games and hitting for a .238 average. In 1910 he hit .237 but showed some power at the plate, clouting four home runs and compiling a .353 slugging average. After two seasons with Anderson, he joined the Nashville Volunteers of the Southern Association in 1911. At Nashville his hitting improved greatly, as he posted a .316 batting average and a slugging percentage of .424. However, toward the end of July he announced that he would retire from baseball at the end of the season. He had continued his engineering studies at Auburn during the offseasons and would graduate in 1912. He was engaged to an Atlanta heiress, Rosalie Eubanks, whose parents had died the previous winter. They planned to marry in the fall. Smith had secured an important position with the Atlanta Traction Company and planned to put his engineering skills to work.

However, events interceded to change his mind. Smith nearly won the Southern Association batting championship in 1911. He and Del Pratt of Montgomery both hit .316, but when the statistic was carried out to four decimal places, Pratt edged the redhead by a margin of .0006. Red’s hitting attracted the attention of Brooklyn scout Larry Sutton, and the Dodgers, or Superbas, as they were sometimes called (the nickname Robins came later), purchased his contract. Smith made his major-league debut on September 5, 1911. In 28 games he hit .261 and won the favor of Brooklyn fans and manager Bill Dahlen. As planned, he married his Rosalie. However, for the next 18 years his career was in baseball, not engineering. From 1911 to August 1914, he played third base for Brooklyn. In 1912 he was the club’s regular third baseman and hit .286. He had perhaps his best year in 1913, when he led the league in doubles and finished in the top ten in hits, total bases, extra-base hits, sacrifice hits, runs batted in, slugging average, and on-base percentage plus slugging average (OPS). Although sportswriter Tom Meany described the right-handed third sacker as a “squatty slugger,” he was listed as 5-feet-11 and 165 pounds.

In November 1913 Dahlen was let go as Brooklyn manager. Many fans advocated popular first baseman Jake Daubert becoming his replacement. Hughie Jennings and Roger Bresnahan also were rumored to be in the running. However, owner Charles Ebbets selected Wilbert Robinson. Although Smith got off to a good start in 1914, he soon clashed with Robinson. He also fell out of favor with the fans, who had supported him so warmly in his early days in Brooklyn. The redhead had threatened to jump to the Federal League and had met with representatives of the league. He also was considered one of a clique of players who were striving to have Robinson replaced as manager by Daubert. Robbie regarded Smith as a trouble maker, and resolved to get rid of him. His chance came when Brooklyn signed third baseman Joe Schultz from the Rochester club The Dodgers sold Smith to the Boston Braves on August 10, 1914. Unfortunately for Brooklyn, Schultz never played a single game in the major leagues that season, and the club was stuck with weak-hitting Gus Getz at the hot corner.

According to Harold Kaese as Smith was leaving the owner’s office after signing his contract, he said, “I’ll see you tomorrow afternoon.” James Gaffney responded, “You mean tomorrow morning.” “What do you mean? Does this club still have morning practice?”

“Yes, sir. Every day except Sunday,” Gaffney replied. Smith laughed and said, “Why, we quit having morning practice a month ago at Brooklyn.” Kaese wrote that Smith reported in uniform bright and early the next morning.1

Smith was an important contributor for Boston down the stretch, hitting .314 with an on-base percentage of .401 for the Braves as they continued their dramatic drive to the pennant. When the Braves acquired Smith, they had already started their climb up the standings and were now in fourth place. Aware of Red’s reputation as a malcontent, Boston manager George Stallings lavished praise on the third sacker, securing him a raise in salary and assuring him that he was just the man to win the championship for the team. The psychology paid off as Smith compiled the highest batting average of any of the Miracle Braves over the course of the 60 games in which he played. His hitting more than compensated for the fact that he had the lowest fielding average on the club during that interval. After all, guardians of the hot corner frequently have the lowest fielding percentage on their clubs.

Unfortunately, a serious mishap befell Smith on the last day of the season. It happened in the ninth inning of the first game of a doubleheader against his former team at Ebbets Field. On that occasion Smith was wearing a new pair of shoes with spikes longer than those he was accustomed to. He hit a long drive that bounced off the right-center-field wall. Red rounded first and headed for second, trying to stretch the hit into a double. As he neared second base he began a hook slide. Meanwhile, Brooklyn’s George Cutshaw received the throw from the outfield and lunged toward the runner. Smith’s right shin struck Cutshaw’s left leg and the long spikes dug into the dirt and threw the whole weight of his body on the ankle joint. His body was thrown several feet past the bag. He was taken by automobile to St. Mary’s Hospital in Brooklyn. The attending physicians reported that Smith had suffered an anterior dislocation of the ankle joint of his right leg, a fracture of the fibula three inches above the joint, a fracture of the tibia, and ruptures of the ligaments of the ankle joint. The doctors were uncertain whether Smith would ever regain full use of the badly damaged ankle. Unable to compete in the World Series, he was temporarily replaced at the hot corner by Charlie Deal. As the Braves never again won a pennant while Smith was with them, the accident deprived him of the only chance he had to play in a World Series.

Red was a good, solid hitter throughout his major-league career. He recovered fully from his broken ankle and played five more years for the Braves. In 1915 he slugged the first grand slam hit at the new Braves Field. He had solid years at the plate for the Braves from 1915 through 1918, hitting .295 in 1917 and a major-league career-high .298 in 1918. Because of a low fielding percentage, Red was sometimes considered a poor fielder. He led the National League in errors three times. However, he had good range in the field, leading the circuit in putouts three times and in assists four times. On June 12, 1919, the Braves secured third baseman Tony Boeckel from Pittsburgh. Manager Stallings moved Smith to the outfield, where he finished his major-league career. In February 1920 he was sent on waivers to the New York Yankees, and a few days later the Yankees sold him to the Washington Senators. He wound up playing for the Vernon Tigers of the Pacific Coast League, and played in the minors until 1928. In his nine seasons in the majors he had played in 1,117 games, hit .278 with an on-base percentage of .353. Among his 1,087 hits were 208 doubles, 49 triples, and 27 home runs. He scored 477 runs and batted in 514.

From 1920 through 1923 Smith was with Vernon and then Los Angeles in the PCL, hitting over .300 in three of the four years. In 1924 and 1925, he was with Atlanta in the Southern Association, leading the league with a .385 average in 1924 and hitting .344 the following year. He split the 1926 season between Atlanta and the Jacksonville Tars of the Southeastern League. The 1927 season was divided between Peoria of the Three-I League and Nashville. His .370 average for Peoria was best in the circuit. He closed out his baseball career in the Class B Three-I League in 1928 with Springfield and Peoria. During his 12 seasons in the minors (including 1909-1911) he played in 1,610 games and collected 1,907 hits, including 339 doubles, 69 triples, and 58 home runs. He averaged .327 and posted a .431 slugging percentage. For his total career—majors and minors combined—he fell short by only six hits of reaching the 3,000 mark.

Smith also garnered some minor-league managerial experience. In 1921 he piloted the Columbia Mules of the Class D Alabama-Tennessee League for a few games. He managed the Jacksonville Tars of the Class B Southeastern League for part of the 1926 season. In 1928 he was skipper of the Springfield Senators of the Three-I League for a partial season. In none of his three managerial experiences did he manage for an entire season.

In 1930 Smith worked as an insurance agent, living in Atlanta with his wife, Rosalie; daughter Margaret; and son James Carlisle, Jr. Later he served as a tax investigator for the city of Atlanta for 27 years before retiring. In his last years he lived in Marietta, a suburb of Atlanta. He was overjoyed when the Milwaukee Braves moved to Atlanta in 1966. His daughter, Margaret, then Mrs. Leo Sudderth, Jr., said her father was the “most enthusiastic booster the Braves had when they moved to Atlanta. …Daddy maintained his interest in baseball through the years. But he was really excited when his Braves came here.” 2

Unfortunately, Smith had only one season in which to cheer the Braves in his hometown. He died at the age of 76 in Atlanta’s Piedmont Hospital on October 11, 1966. The cause of death was listed as aortic insufficiency brought on by congestive heart failure. He is buried in Westview Cemetery in Atlanta.

This biography is included in “The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston’s Original Worst-to-First World Series Champions” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Red Smith player file in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Frank Graham. The Brooklyn Dodgers: An Informal History. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1945.

Jack Kavanagh and Norman Macht. Uncle Robbie. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1999.

Harold Kaese. The Boston Braves, 1871-1953. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004.

Tom Meany. Baseball’s Greatest Teams. New York: A.S. Barnes and Co., 1949.

Notes

1 Kaese, p. 147

2 United Press International dispatch from Atlanta, carried in the Lima News, October 12, 1966.

Full Name

James Carlisle Smith

Born

April 6, 1890 at Greenville, SC (USA)

Died

October 11, 1966 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.