Rico Carty

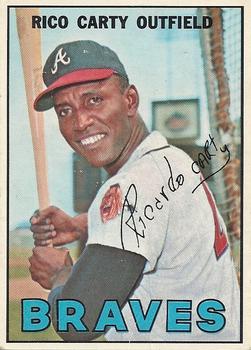

In 1964, a 24-year-old Dominican strongman named Ricardo Adolfo Jacobo (Rico) Carty burst into the major leagues like a tropical storm. After two hitless at-bats in 1963, Carty’s batting average (.330) in his first full season was the second highest in the majors. Only Roberto Clemente hit better, and only a phenomenal year by Philadelphia’s Richie Allen prevented Carty from being voted Rookie of the Year. He had exceeded the high expectations created by a stellar four-year minor-league apprenticeship and quickly became “one of the most popular players ever to wear a Milwaukee uniform.”1 After the Braves relocated, his popularity grew in Atlanta, where the left-field stands became known as “Carty’s Corner.”2

In 1964, a 24-year-old Dominican strongman named Ricardo Adolfo Jacobo (Rico) Carty burst into the major leagues like a tropical storm. After two hitless at-bats in 1963, Carty’s batting average (.330) in his first full season was the second highest in the majors. Only Roberto Clemente hit better, and only a phenomenal year by Philadelphia’s Richie Allen prevented Carty from being voted Rookie of the Year. He had exceeded the high expectations created by a stellar four-year minor-league apprenticeship and quickly became “one of the most popular players ever to wear a Milwaukee uniform.”1 After the Braves relocated, his popularity grew in Atlanta, where the left-field stands became known as “Carty’s Corner.”2

Lofty predictions regarding Carty’s future did not materialize due to an unfortunate combination of illness, injuries, ineptitude on defense, and a reputation as a troublemaker. Concerns about Carty’s prowess in the field plagued him throughout his seven seasons with the Braves. His 1973 move to the American League –which included an abbreviated appearance with the Oakland Athletics — coincided with the birth of the designated hitter, which most baseball people thought fit Rico like a glove, but Carty initially resisted.3 Poor performance in his first year as a DH seemed to have ended his career, but a good season in the Mexican League earned Carty the chance to resurrect his career.

Rico Carty’s baseball journey began in San Pedro de Macoris, Dominican Republic, where he was born on September 1, 1939, one of 16 children. His mother, Olivia, was a midwife; his father, Leopoldo, worked in the sugar mill and played club cricket.4 Rico played pick-up baseball until he was 15, when he followed the example of four uncles and turned to boxing. He won his first 17 bouts (12 by KOs), but turned to baseball full-time after one embarrassing ring defeat.5

In 1959 Carty joined (as a catcher) the Dominican team that played in the Pan-Am Games in Chicago, and he attracted considerable attention. Eight major-league teams and four Dominican League clubs offered him contracts, and the naïve youngster signed them all. George Trautman, head of minor-league baseball at the time, resolved the resulting dispute in favor of Milwaukee.

Carty’s professional baseball career began in 1960 with Davenport/Quad Cities in the Class-D Midwest League. He struggled both with the English language and with minor-league pitching, but moved up to Class-C Eau Claire in 1961. In 1962, at Class-B Yakima, Carty showed the hitting skills that would ensure his future success. He also showed the penchant for injury that would limit that success. His .366 average was leading the Northwest League when he tripped over first base, pulling a leg muscle and ending his season. He lost the batting race but made the year-end league All-Star team and was the Topps Class-B All-Star catcher.

Carty started the 1963 season at Triple-A Toronto, where he was hailed as “the best catching prospect … in 10 years.”6 Even so, he was sent down to Double-A Austin to be converted into an outfielder because the Braves had a bevy of young backstops. The only blemish on Rico’s season, and perhaps another portent of the future, came when he decked a spectator for heckling him.

Despite his late arrival, Carty ended the season among Texas League leaders with a .327 average, 27 home runs, and 100 RBIs. He made his major-league debut on September 15, 1963, striking out as a pinch-hitter. The future looked bright for Carty, who was now being touted as “the best young hitting prospect in the [Braves] organization.”7 He had an outstanding 1963-64 season in the Dominican League and then married Gladys Ramirez de Jacobo. They would have six children, who produced 16 grandchildren.8 One son, Rico Jr., played 16 games as a Seattle Mariner farmhand.

After Carty’s fine winter season, Braves farm director John Mullen compared him to Orlando Cepeda,9 and his Grapefruit League performance justified the praise. He hit .408 and led the team with 13 RBIs. Carty made the Braves’ 1964 Opening Day roster, but did not play regularly at first as manager Bobby Bragan tried to balance playing time among his outfielders (Hank Aaron, Felipe Alou, Lee Maye, and Carty). When Alou was hurt in late June and Rico took over in left field, the Braves won 16 of their next 23 games. In late August, he ended a rare batting slump in dramatic fashion, delivering two 5-for-5 days within a week. He led the Braves in batting (.330) and slugging (.554), and made Topps’ Rookie All-Star Team.

In January Carty became the first Brave to sign his 1965 contract (for a salary of $17,500).10 He had a strong season in winter ball and reported for spring training, where Bragan was determined to transform him into a first baseman. Rico never mastered the new role and injured his back while trying to do so. Carty’s back ailment kept him out of the lineup often throughout that season; he never played more than a week at a time. He complained that Bragan often jerked him from the lineup late in games, undermining his confidence,11 but Carty’s fielding lapses often justified the manager’s actions. Late in the season, a doctor discovered that Carty’s right leg was slightly shorter than his left and prescribed a corrective shoe, quieting those who had accused the slugger of exaggerating his back pain.

While the 1965 season was disappointing, Carty hit when he played, compiling a .310 average in 83 games (all in left field). He also demonstrated his willingness to speak out when he thought he’d been wronged. Both traits continued throughout his career — as did frequent trade rumors, which began to circulate during that offseason.

Carty spent the winter of 1965-66 in a new environment, playing winter ball for the Aragua Tigers in the Venezuelan League. He wore his new orthopedic shoe and led the league with a .392 batting average and 13 home runs, a new season record. When he returned to the US, he was again headed for a different setting — the Braves’ new home in Atlanta — and renewed enthusiasm about his potential to become “the next great hitter in the National League”12 Even so, he was the Braves’ fourth outfielder, behind Aaron, Alou, and Mack Jones.

On June 4, 1966, Carty was inserted into the lineup as the starting catcher, and the Braves promptly won seven consecutive games as Rico went 12-for-24. But after nine games, he was back in left field. Trade rumors continued, but Carty was in the lineup to stay. He played in 151 games, even filling in at first base and third base, and hit .326 (third in the NL). During the offseason, Carty was the Brave most sought after player in trade, but the team now saw him as “the next NL batting champ.”13

Before returning to the Dominican League for winter ball, Rico signed his 1967 contract (in the $25,000 range). He had another good season with the Estrellas Orientales, but his temper flared again, garnering him a $50 fine for insulting an umpire, and his injury jinx reappeared as he was hurt in a car crash.

The 1967 season began with optimism in Atlanta. The team had finished fifth in 1966, but had compiled a winning record (33-18) after Billy Hitchcock replaced Carty’s nemesis Bragan. Those hopes faded quickly, however, as both the Braves and Rico had dismal seasons. The Braves fell to seventh place, and Carty had his first sub-.300 season in the majors, although he was relatively injury-free. The low moment of the season came on June 18, when Carty engaged in a “brief but heated scuffle” with Hank Aaron.14 At the time, details were scarce, but Aaron later said that he was angry because Carty had loafed on a ball into the outfield and had called him a “black slick.”15 At season’s end, the Braves were actively seeking trades, and Carty was “among the most likely to go.”16

Carty won the 1967-68 Dominican League batting title (.350) and led Estrellas to the regular-season title and the playoff championship. He reported for spring training down ten pounds to his “fighting weight” of 190 and downplayed teammate Clete Boyer’s offseason criticism (echoing Aaron’s) that Carty “doesn’t give 100 percent.”17

Three weeks into 1968 spring training, Carty’s injury jinx struck with a vengeance. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis. While the disease was “not as serious as first suspected,” Rico was lost to the Braves for the season.18

When he reported for spring training in 1969, a rejuvenated Carty tied for the team lead in batting (.333) during the spring, but a dislocated shoulder put him on the disabled list on Opening Day. He finally got into a game on May 2 as a pinch-hitter and responded with a game-tying sacrifice fly. In his first start, on May 18, he re-injured that troublesome shoulder and missed another two weeks.

Carty was in and out of the lineup for much of the season, but returned to spark the Braves in their stretch drive to the first NL West division title. He had hits in 19 of the final 21 games (17 Atlanta wins), averaging .383 and driving in 22 runs. He drove home the game-winning run in the division-clinching game and finished the season with a team-leading .342 average in 104 games.

The Braves lost that first League Championship Series in three straight games to the New York Mets, but Carty played well in what would be his only postseason appearance, hitting .300 and compiling a .462 on-base percentage and a .500 slugging average, but with no RBIs. He finished a surprising second to Tommie Agee as the NL Comeback Player although, as Hank Aaron observed, Agee “only came back from a bad year [while] Rico came back off a hospital bed.”19

Carty hit .333 in the Dominican League that winter. He was also fined $50 and suspended for three days for shoving an umpire. Major League Baseball later added a $500 fine for “inexcusable and intolerable” conduct.20

Carty opened the 1970 season even better than he had ended 1969. He would have been a shoo-in for All-Star selection by the fans, but his name wasn’t on the ballot. The list of 48 candidates in each league had been compiled during spring training, and Carty wasn’t included. The fan voting period began on May 16, the day that saw the end to Rico’s 31-game hitting streak, a team record that lasted until 2011. More than 2 million fans voted, and Rico received 552,382 votes (67,000 more than Pete Rose) to join Hank Aaron and Willie Mays in the NL’s starting outfield as the first “write-in” All-Star.

Carty injured his wrist just before the All-Star Game, but started the game, batting twice (a walk and a groundout) before being replaced. In the latter half of the season, he suffered other injuries (a pulled leg muscle and a chipped bone in his finger caused when he was hit by a pitch), but he led the NL in batting average (.366) and on-base percentage (.454). In the midst of his best season ever, however, Rico was involved in another fight with a teammate — pitcher Ron Reed. Carty insisted afterward that “it was just a misunderstanding,”21 but he was on the trading block despite having the highest career batting average among active players.22 Sports columnist Dick Young suggested that Carty was an excellent choice for any team “looking for a big bat and willing to accept a big headache.”23

On December 11, 1970, a different form of physical conflict took Carty off the market; he collided with Dominican League teammate Matty Alou and suffered a fractured knee and ligament damage. He was flown to Atlanta for surgery on what a team doctor called “as bad a knee injury as an athlete can have.”24 With his career in jeopardy, he returned home to recover — after signing a contract that included a raise over his 1970 salary of $45,000.

Carty reported for 1971 spring training with his leg in a brace, and he hobbled out of the dugout on Opening Day to a standing ovation. He took batting practice on July 18 and hit the first pitch he saw off the top of the fence in left field. He was scheduled to return to the lineup on August 5, when the first 15,000 fans would receive buttons that read “SMILE — the Beeg Boy’s Back.”25

But a blood clot in his damaged leg ended any hope of a comeback, and Carty missed his second full season in four years. His bad luck didn’t end there, however. On August 24 he and his young brother-in-law were involved in a fight with two off-duty Atlanta policemen when Rico took umbrage at a racial slur. Atlanta Mayor Sam Massell labeled the incident “blatant brutality” and suspended the officers.26

Although Carty played only sporadically during spring training and seemed destined to start the 1972 season as a pinch-hitter, he received a $50,000 contract after a trial period imposed by the Braves because of concerns about his physical condition. He hit well when he played, but developed elbow tendinitis and went on the disabled list with a pulled hamstring. He played in only 86 games that season and hit just .277. Though his career batting average (.315) was still the highest among active players,27 in October the Braves traded him to the Texas Rangers.

Neither the Atlanta press nor Braves fans were happy about the trade, but Rico said he was not surprised because he and new manager Eddie Mathews were not on good terms.28 Rangers GM Joe Burke admitted that some would call the trade a gamble, but expressed confidence that Carty had matured and was eager to play.29 New Rangers manager Whitey Herzog emphasized that he was looking for “ballplayers, not Boy Scouts” — a description that certainly fit Rico Carty. 30 Then Carty suffered another Dominican League injury; a pitch from Pedro Borbon fractured his jaw.

There was good news, however. The American League had adopted the designated-hitter rule, and Herzog called Carty “the perfect man for such a role.”31 Rico did not agree. The man whose defensive skills had been described as “amusing at best”32 and who had accumulated more outfield errors (40) than assists (31) wanted to play on defense.

During 1973 spring training, Rico took a parting shot at the Braves, again singling out Eddie Mathews for criticism.33 Word leaked out that Carty had won a $20,000 judgment against the Braves, whom he accused of shortchanging him by not sharing the funds the team received (under an agreement between MLB and the Dominican League) after his 1971 knee injury.34

On the field things were not going well for Carty. By early June his .203 average had cost him the Rangers’ DH job. He was back in left field and feuding with his manager.35 When he was sidelined after breaking a small bone in his foot sliding into second base on July 19, Rico’s initial foray into the American League was over. He was hitting only .232 with three homers and 33 RBIs in 86 games for the Rangers when the Chicago Cubs acquired him on waivers on August 13.

Carty made his Cubs debut the following day, grounding out as a pinch-hitter in a loss to the Braves. The next day, he was batting cleanup and did so for most of his time with Chicago. His best day as a Cub came on August 28 in his first game as a visitor at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium; he hit a two-run homer in his first at-bat and later singled to drive in two more runs in a 9-6 Cubs win. That was his only home run for the Cubs and half of his RBIs, and on September 11, after 22 games with the Wrigleyites, Carty was sold to the Oakland Athletics. He again demonstrated his willingness to attack local legends, blaming his demise in Chicago on Ron Santo, whom he called a “selfish ballplayer.”36 The more likely reason was his .214 batting average and .257 slugging percentage — both career lows.

The Athletics were leading their division by six games when they acquired Carty “for reasons unclear to outside observers,” and they finished the season in the same position.37 Rico appeared in seven of the Athletics’ final 18 games, hitting .250 (2-for-8) and getting his only RBI with a solo home run. The A’s went on to win the World Series, but Rico was not eligible for postseason play. When he was released on December 12, Rico complained that he had gotten only a termination telegram from the A’s, who “didn’t give me a Series share, a ring, a handshake — nothing at all.”38

Everyone except Carty thought his career was over. He played winter ball in Mexico and then signed with Cordoba in the Mexican League, where his performance justified his self-confidence. He hit .354 (second in the league) with 11 home runs and 72 RBIs in 112 games,39 and the Cleveland Indians, who were in a tight divisional pennant race, signed Rico to a $72,000 annual contract through the 1975 season. After 11 hitless at-bats, his first Tribe hit was a two-out, ninth-inning, game-tying RBI single. He then fought through a pulled hamstring to hit .363 in 33 games as a designated hitter and first baseman.

Carty was back with Cleveland in 1975, and the 35-year-old hit .308 and tied for the team lead in game-winning RBIs (9). He was even better in 1976, hitting above .400 until injuries once again shelved him. He played in a career-high 152 games, compiled a .310 batting average, and led the team with 83 RBIs. He had even become a fan of the DH rule, and Cleveland’s baseball writers voted him Man of the Year.40

Despite this performance, the Indians did not protect Carty in the 1976 expansion draft. The Toronto Blue Jays made him their fifth pick but quickly traded him back to the Indians. In 1977 he was the highest-paid Indian, making an estimated $90,000, but he started slowly.41 He was hitting .200, and the team was in the division cellar (4-9) when he accepted the Wahoo Club’s 1976 Man of The Year award with “one of the strangest acceptance speeches in history,” criticizing manager Frank Robinson, who shared the head table, for “lack of leadership.”42 Carty had taken his reputation for confrontation to a new level, and when Robby fined Rico for “insubordination” after a June 6 dugout clash, local writers speculated that Carty would soon be traded.43

Instead, less than two weeks later, Robinson was fired. Carty finished the season hitting “only” .280 while leading the team in RBIs (80). He signed on with Cleveland for 1978, but when the Tribe acquired Willie Horton, Carty became expendable and was traded to the Blue Jays during spring training.44

Carty had 19 RBIs in April for Toronto. His troublesome hamstring again put him out of action briefly, but in a seven-game August homestand, Rico hit three homers and drove in six runs, bringing his season totals to 20 and 68, new franchise records. That was his farewell performance for the Jays, who soon traded Carty to Oakland for Willie Horton, whose arrival in Cleveland had led to Rico’s departure.

Carty quickly made the trade look extremely one-sided in favor of the A’s. After going hitless in his first game, he went on a 15-game hitting streak — two short of the club record. He hit eight homers in his first 19 games with Oakland and continued to top Horton’s Toronto performance in every important offensive category. Carty’s 31 homers for the season were his career high and set a new record at the time for designated hitters.

Carty made it clear that he intended to test the free-agent market in 1979 and indicated that his next team would be his last. Even so, the Blue Jays reacquired Rico, believing they could sign him because they could play him every day.45 When Carty was granted free agency, four teams sought him, but the Blue Jays signed him to a five-year partly-guaranteed contract for $1.1 million plus an immediate loan of $120,000 — not bad for a 39-year-old player with a history of frequent injuries.46 Carty’s 31-page contract was described as “probably the bulkiest in the history of baseball.”47

After skipping winter ball, Carty pulled a calf muscle in spring training and hit under .200. The regular season saw no major improvements. In early June he was hitting only .250 and was the target of boos from Toronto fans. On July 1 he was benched after hitting only one homer in almost two months. Carty blamed his slump on a “freakish injury” — a swollen hand caused when he accidentally stabbed himself with a toothpick.48 That 1979 season had few highlights for Rico, but on August 6 he hit his 200th career home run, becoming the oldest player (at 39 years, 339 days) to achieve that milestone. Overall, however, it was his worst season except for 1973, when he had shuttled among three teams. When Jays manager Roy Hartsfield was fired after that season, he observed that it had been “hard to live with Rico Carty’s virtual lifetime deal.”49

Hartsfield’s successor did not have that challenge. Carty hit poorly in winter ball, where he was again hampered by a leg injury, and was still favoring his calf when spring training started. He was unconditionally released on March 29, 1980. His “lifetime” deal as a player had lasted one year, although he still worked for the Blue Jays as a Latin American scout.

Carty’s major-league playing days were over, and his lifetime batting average had dropped to .299. Early visions of superstardom had not been realized, but, despite losing two entire seasons to illness and injury, he had played 13 seasons in the majors. He was big (6-feet-2) and slow, but he was a natural-born hitter. The flamboyant, self-described “Beeg Boy” made more comebacks than a boomerang, and few who saw him play will ever forget his aggressive right-handed swing and his trademark one-handed catches. He was a study in contrasts — known for his infectious grin and also for his fierce glare at the plate; popular because of his cheerful banter with fans yet branded a troublemaker. Carty argued that the latter reputation was unfounded, claiming he simply “stood up for his rights.”50 The record shows that he defended those rights frequently and that he was an equal-opportunity combatant, engaging in physical and/or verbal conflicts with teammates, managers, umpires, fans, local police, and at least one front office.

Rico Carty remained a hero in his homeland, where he lived as of 2014. During his playing days, he returned to the Dominican Republic almost every year to play winter ball, saying, “I owe my country a lot.”51 He retired as the Dominican League’s all-time home run leader (59). That record was eclipsed, but Carty’s legend survived. He didn’t get to Cooperstown, but he is enshrined in two Halls of Fame, the ones honoring heroes of Caribbean Baseball (1996’s inaugural class) and Latino Baseball (2011). He is an honorary general in the Dominican Army,52 and he once thought he had been elected mayor of his hometown until a recount proved otherwise.53

Baseball gave Carty financial security,54 and he stayed active in the game at home and elsewhere. In 1988 Rico led the Dominican team to a third-place finish in the first Men’s Senior Baseball League World Series and won the home run contest in the 40-plus age bracket. League founder Steve Sigler said, “He’s still an amazing hitter [at age 49], and he was the only one using a wooden bat.”55 He may have summarized Rico Carty’s career: The “Beeg Boy” could hit … and he did things his way.

Postscript

Carty died at the age of 85 on November 23, 2024.

Author’s note

I regret that this biography was completed without input from the subject. Extensive efforts to locate Rico Carty were fruitless. One representative of the Atlanta Braves said that Rico “has dropped off the map.” Obviously, there is plenty of information on his career; I hope I have done him justice. If not, I’m sure he will let me know.

Sources

Aaron, Hank, with Lonnie Wheeler. I Had A Hammer (New York: Harper-Collins, 1991).

Kurlansky, Mark. The Eastern Stars: How Baseball Changed the Dominican Town of San Pedro de Macoris (New York: Riverhead Books, 2010).

Ruck, Rob. The Tropic of Baseball: Baseball in the Dominican Republic (Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books, 1999).

—— Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game (Boston: Beacon Press: 2011).

Atlanta Braves Illustrated Yearbooks (1966-1972)

Chop Talk, the official monthly magazine of the Atlanta Braves

Milwaukee Braves Yearbook, 1964

Milwaukee Journal, Sarasota Herald-Tribune, Sports Illustrated, baseball-almanac.com, baseballprospectus.com, baseball-reference.com, hardballtimes.com, MLBlogsNetwork (mlb.com), and retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Bob Wolf, “Rookie Rico Set Off Tom-Tom Beating by Braves’ Faithful,” The Sporting News, July 25, 1964.

2 Wayne Minshew, “Friendly Rico Rates Tops on Tepee List,” The Sporting News, July 12, 1969.

3 Randy Galloway, “Carty Shuns DH Job — I’m No Invalid,” The Sporting News, March 24, 1973.

4 Rob Ruck, Raceball, 202-204.

5 Mark Kurlansky, The Eastern Stars: How Baseball Changed the Dominican Town of San Pedro de Macoris,

6 “Leafs Rave Over Kid Carty,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1963, 33.

7 Bob Wolf, “Braves Examine Hot-Shot Kids In 1964 Blue Print,” The Sporting News, September 28, 1963.

8 Chris Boone, “Carty Still Loves the Braves,” ChopTalk, April 26, 2006.

9 Bob Wolf, “Carty Rated Excellent Chance to Crash Braves Picket Party,” The Sporting News, January 18, 1964.

10 Bob Wolf, “Braves Load Their Bench With Wallop in Oliver Bat,” The Sporting News, January 16, 1965.

11 Bob Wolf, “Carty Lets Out Yelp In Bragan’s Doghouse,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1965.

12 Furman Bisher, “Ache-Free Carty May Put New Punch In Tepee Bats,” The Sporting News, March 19, 1966.

13 “ ‘Everybody at Convention Eyed Carty,’ Says McHale,” The Sporting News, December 17, 1966, 30.

14 “Aaron-Carty Feud Explodes on Plane After No-Hitter,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1967, 12.

15 Hank Aaron, with Lonnie Wheeler, I Had a Hammer, 190.

16 Wayne Minshew, “Braves Cut Price Tags, Seek Deals,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1967.

17 Jay Searcy, “Clete Takes Verbal Jab at Rico; ‘He Loafs,’ Claims Third Sacker,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1968.

18 Wayne Minshew, “TB Kayoes Carty for Year,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1968.

19 Wayne Minshew, “Same Old Rico — He’s Hitting a Ton,” The Sporting News, February 14, 1970.

20 The Sporting News, February 21, 1970: 49.

21 “Reed, Carty Have Fight Before Game,” Milwaukee Journal, August 21, 1970.

22 Frank Eck, “Two-Year Tempo of .356 Lifts Carty to Lofty .321 for Career,” The Sporting News, November 14, 1970.

23 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, September 12, 1970.

24 Wayne Minshew, “ ‘With God’s Help, I’ll Be Back’ — Carty,” The Sporting News, January 30, 1971.

25 “Smile — That Beeg Boy’s Coming Back to Braves,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1971: 30.

26 “Carty Beaten; Atlanta Policemen Suspended,” Sarasota Herald-Tribune, August 26, 1971.

27 Bob Fowler, “Killer, Oliva Express Doubt Over DH Rule,” The Sporting News, February 3, 1973.

28 Wayne Minshew, “Braves Swapping of Carty Puts Mathews on Hot Seat,” The Sporting News, November 18, 1972.

29 Merle Heryford, “Rangers Get Carty to Beef Up Attack,” The Sporting News, November 11, 1972.

30 Randy Galloway, “Herzog Seeking ‘Ballplayers, not Boy Scouts,” The Sporting News, December 23, 1972.

31 Oscar Kahan, “DH’s May Give Needed Hypo to AL,” The Sporting News, January 27, 1973.

32 Peter Carry, “Player of the Week,” Sports Illustrated, September 14, 1964

33 Wayne Minshew, “Carty Fires Volley at Mathews,” The Sporting News, April 7, 1973.

34 Jerome Holtzman, “Reuschel Hungry for 20-Win Season,” The Sporting News, May 19, 1973.

35 Merle Heryford, “Rico-Whitey Spat Ends in Truce,” The Sporting News, June 23, 1973.

36 Ron Bergman, “A’s Acorns,” The Sporting News, October 6.

37 Ron Bergman, “A’s Have a Credo: Do Jobs the Hard Way,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1973.

38 Sarasota Herald-Tribune, August 25, 1974.

39 Cleveland Indians roster, The Sporting News, March 15, 1975.

40 On his sentiments regarding the DH rule, see Russell Schneider, “Carty’s Ex-Bosses Wince — But Injuns Grin at Hot DH,” The Sporting News, June 12, 1976.

41 Milton Richman, “Average Regular’s Pay Rockets to $95,149,” The Sporting News, April 23, 1976.

42 Russell Schneider, “Tepee Totters From Oral Blasts at Robinson,” The Sporting News, May 14, 1977.

43 Russell Schneider, “Carty Exit Almost Certain After Hassle With Robby,” The Sporting News, June 25, 1977.

44 Neil McCarl, “Jays Get Carty and Bosetti to Beef Up Anemic Attack,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1978.

45 Neal McCarl, “Jays Miss Goal, Post 102 Losses,” The Sporting News, October 21, 1978.

46 Murray Chass, “Ten Aging Free Agents Hit $15 Million Jackpot,” The Sporting News, March 3, 1979.

47 Murray Chass, “Carty’s Pact 31 Pages Long,” The Sporting News, March 3, 1979.

48 Neil McCarl, “Howell Returns With Hot Bat and Tongue,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1979.

49 Stan Isle, “Kroc Also Big in Milk — Milk of Human Kindness,” The Sporting News, November 17, 1979.

50 Russell Schneider, “Rico’s Bat a Bargain Buy for Indians,” The Sporting News, September 14, 1974.

51 Rob Ruck, The Tropic of Baseball: Baseball in the Dominican Republic, 161.

52 Bruce Markusen, “Card Corner: Rico Carty,” Hardball Times, October 8, 2010.

53 Bruce Markusen, “Cooperstown Confidential,” MLBlogsNetwork, July 6, 2005 (mlb.com).

54 Rob Ruck, The Tropic of Baseball, 161.

55 Bob McCoy, “Keeping Score: Never Over the Hill,” The Sporting News, November 21, 1988.

Full Name

Ricardo Adolfo Jacobo Carty

Born

September 1, 1939 at San Pedro de Macoris, San Pedro de Macoris (D.R.)

Died

November 23, 2024 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.