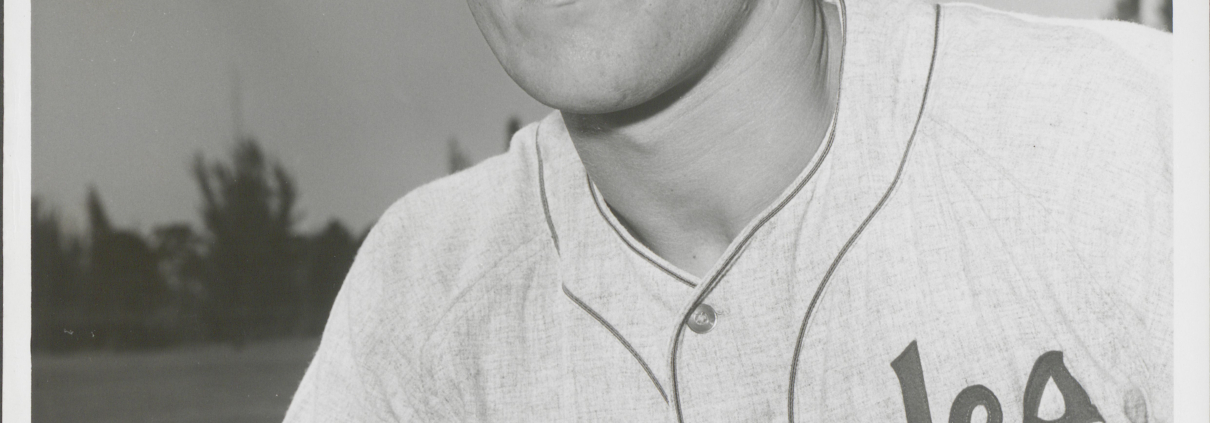

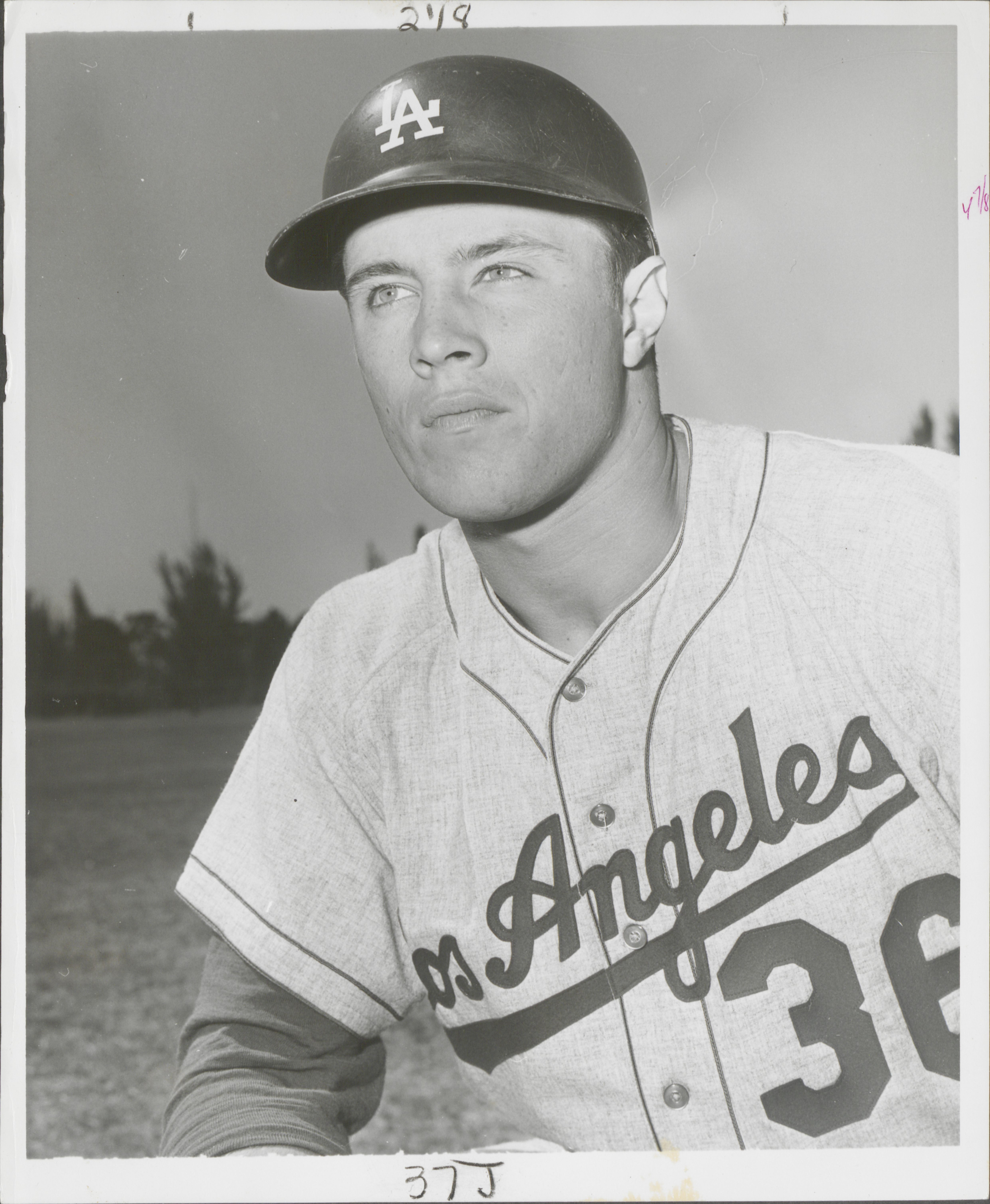

Roy Gleason

While he made one hit in his only major-league at-bat in 1963, Roy Gleason is better known for the unfortunate one hit of shrapnel he incurred in 1968 from an enemy bomb explosion while serving in the US Army during the Vietnam War. Gleason, who had played five years in the minor leagues before he was drafted into the military in 1967, earned a Purple Heart and recovered from his wounds to play one more year of minor-league baseball.

While he made one hit in his only major-league at-bat in 1963, Roy Gleason is better known for the unfortunate one hit of shrapnel he incurred in 1968 from an enemy bomb explosion while serving in the US Army during the Vietnam War. Gleason, who had played five years in the minor leagues before he was drafted into the military in 1967, earned a Purple Heart and recovered from his wounds to play one more year of minor-league baseball.

Roy William Gleason was born on April 9, 1943, in Melrose Park, Illinois, the middle child of Richard, a truck driver, and Molly (Gorr) Gleason.1 Roy and his two sisters initially grew up in La Grange, Illinois, a town 15 miles west of downtown Chicago, before the family moved to Southern California in 1954 and resided in a ranch-style house in Garden Grove, a suburb 35 miles southeast of Los Angeles.2

In 1956 Roy was stunned when his father left the house “to make a phone call” and never returned. “Now what do we do?” Roy thought at the time, in his newfound role as 13-year-old man of the house. “I knew that I couldn’t undertake the responsibility of supporting my mother and sisters. I remember telling myself that baseball was the answer. If I worked really hard at what I excelled in, perhaps I’d be able to do it.”3 When Roy entered Garden Grove High School in the fall of 1957, the Brooklyn Dodgers formally announced that the ballclub was relocating to Los Angeles for the 1958 season. The Los Angeles Dodgers provided the big break that Roy sought to support his now-fatherless family.

Roy had a spectacular varsity baseball career at Garden Grove High School as a tall, lanky outfielder and right-handed pitcher. But it was summer ball where Roy captured the attention of scouts from several major-league clubs. Playing for the local American Legion team in the summer of 1958, he attracted the attention of Dodgers scout Kenny Myers, who was so smitten with his potential as a ballplayer that he worked with Roy during the winter to hone his batting skills and turn him into a switch-hitter.4 During the summer of 1960, Roy advanced to play for the Dodger Rookies, an elite amateur team managed by Myers.5 Since the summer team was sponsored by the major-league Dodgers, Roy had increased visibility within the Dodgers organization during his high-school years.

All the attention by the Los Angeles Dodgers hooked Roy, who signed with the club on June 16, 1961, the night of his high-school graduation.6 “I wanted to play for the Dodgers, and I wanted to repay Kenny for his investment,” Gleason explained his decision many years later.7 He was so eager to sign with the Dodgers that he turned down a $100,000 offer from the Los Angeles Angels, the American League expansion club. Instead, Roy accepted a $55,000 deal from the Dodgers, which consisted of a $50,000 signing bonus, payable in five annual installments, plus $5,000 payable directly to his mother as “agent.”8

Because many publications reported his signing bonus to be $100,000, Gleason was included in the informal listing of the dozen or so “bonus baby” high-school players who had signed six-figure contracts in 1961, topped by Bob Bailey and Lew Krausse.9 In this era before the institution of the amateur draft in 1965, a big contract given to an inexperienced 18-year-old created enormous expectations by the ballclub that signed him. The Dodgers touted the 6-foot-5, 220-pound, switch-hitting Roy as a top outfield prospect, expecting this “Dodger-of-tomorrow” to mature into a five-tool player at the major-league level.10 Dodgers coach Pete Reiser told sportswriters that “Roy Gleason has such tremendous power he could become a better long-ball hitter than Duke Snider.”11

The Dodgers placed Roy on the club’s 40-man roster to avoid losing him in the minor-league draft.12 This meant that he was paid the major-league minimum salary, which in 1962 was $7,000, in addition to his annual $10,000 signing-bonus installment.13 Roy was now the breadwinner in the Gleason family. During this Cold War era when young men were actively being drafted into military service, Roy’s local Selective Service board issued him a 3-A draft classification, which exempted him from the draft because he was the sole support for his mother and younger sister.14

Rather than send Roy to the minor leagues in 1961, the Dodgers directed him to play another summer with the Dodger Rookies, a team now comprising recently signed high-school players, and then sent him to the Arizona Instructional League that fall.15 For the 1962 season, the Dodgers assigned Roy to their Reno (Nevada) farm club in the Class-C California League, where he had a decent year with 22 home runs, 76 RBIs, and a .234 batting average, but also a league-high 214 strikeouts.

For the 1963 season, Gleason played for Salem (Oregon) in the Single-A Northwest League, where he hit 15 home runs, had 60 RBIs, and batted .254. He finished strong, though, hitting 12 homers during the last two weeks of the season after he modified his batting stance to lower his hands, a change the exhausted ballplayer adopted after a late night out on the town.16

Despite his modest hitting numbers, Gleason was called up to the Dodgers in September when major-league rosters were expanded, primarily for his speed on the basepaths. The Dodgers, in a heated battle with the St. Louis Cardinals for the National League pennant, needed an ace pinch-runner during the stretch drive to run for hard-hitting but slow-footed Bill Skowron. Gleason appeared in seven games for the Dodgers as a pinch-runner. On September 3 he made an impact in his first appearance, scoring the tying run on a sacrifice fly in a game the Dodgers went on to win. He scored another run on September 5, an insurance run in the eighth inning of another Dodgers victory.

After the Dodgers had clinched the pennant, manager Walt Alston gave Gleason an opportunity to bat in the eighth inning of the September 28 game, when the Dodgers were losing 12-2 to the Phillies. “Gleason, get a bat. You’re batting for Ortega,” Gleason recalled how Alston barked at him while he sat at the far end of the bench. “I guess it was good in that I didn’t have time to think about it. It was an adrenaline rush, ‘Holy cow, I’m going to hit.’ I had been frustrated, pinch-running but not getting any at-bats.”17 However, “He didn’t tell me until Philadelphia was already on the field and the pitcher was already warmed up. So I barely had time to grab a bat and run up to the plate as the umpire is looking over at the dugout to see who is hitting.”18

On the second pitch from Dennis Bennett, Gleason doubled to left field. When he eventually scored a meaningless third run, the few remaining spectators at Dodger Stadium politely applauded. “When the game ended, I realized that my at-bat was an amazing moment in my young life. It signaled the accomplishment of a goal, the manifestation of a dream,” he recalled. “I hoped that Walt would give me more opportunities during the next season.”19 However, Gleason was destined to finish his big-league career with a 1.000 lifetime batting average.

After the Dodgers swept the Yankees to win the 1963 World Series, Gleason received $250 as his share of the players’ proceeds (much less than the full share of $12,794).20 The Dodgers also awarded him a ring for his September pinch-running contribution to winning the pennant.21

In 1964 when Gleason didn’t make the Dodgers roster in spring training, he was sent to the Albuquerque (New Mexico) farm club in the Double-A Texas League. However, after just 15 games, he was optioned back to Single-A Salem, where he finished the season with a .254 average (and 148 strikeouts). After this mediocre performance, the Dodgers dropped him from their 40-man roster and assigned him to their Spokane (Washington) farm club in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League.22 With this demotion in status, the Dodgers seemed to give up on the once-promising prospect.

Gleason never played in a game with Spokane in 1965, though, due to a spring-training injury.23 When he was ready to play again, Spokane optioned him back to Single-A Salem, where he hit a miserable .144 in 51 games.24 By July he had tried unsuccessfully to convert into a pitcher to try to remain a prospect for the Dodgers.25 He then spent the rest of the 1965 season with Santa Barbara of the Single-A California League, where his performance remained poor, with a .129 batting average in 47 games. Gleason, 22 years old and in receipt of the final installment of his signing bonus, had a minimal chance to once again wear a Dodgers uniform. He was no longer a vaunted Dodger-of-tomorrow.

Although he was exposed to the minor-league draft after the 1965 season, no other club sought to obtain his services, probably leery of a future change in the bachelor’s military-draft status in light of the escalation of the Vietnam War. Ballclubs usually encouraged their young unmarried players to join the National Guard or Army Reserve to avoid the military draft. Gleason claimed the Dodgers never advised him to enlist in either organization, though, under the belief that his 3-A draft exemption would last the duration of the war.26 During 1965, however, draft inductions of men aged 18 to 26 doubled and the draft exemption for married men was curtailed to apply just to those who supported a family, not just a wife without children, which ballclubs might have believed would imperil his “hardship to dependents” deferment.27

During the 1966 season, there was little uptick in Gleason’s baseball performance, as he hit .173 in 45 games at Double-A Albuquerque before finishing the season with the Tri-City team of the Single-A Northwest League. Although he had his best minor-league stint at the team in Washington state (.281 average, league-leading 16 home runs), it was too little, too late. The Dodgers, who had won consecutive National League titles in 1965 and 1966, were focused on the development of other young outfielders.

When Gleason went to 1967 spring training with the Dodgers in Vero Beach, Florida, local draft boards were reconsidering the draft-exempt status of professional athletes amid congressional concern about “the apparent immunity of professional athletes from the military draft.”28 Although he had a draft deferment during his five years in the Dodgers minor-league system, he was supporting his mother and soon-to-be-18-year-old sister, not a wife or children. In 1967 during a firestorm of public concern about the apparent favoritism of athletes to avoid military duty, his case for supporting dependents was much weaker than when he had signed with the Dodgers back in 1961. An omen surfaced when the Army drafted New York Yankees rookie Bobby Murcer in February of 1967.29

Gleason’s local draft board reclassified him 1-A and “fit for service” in March of 1967.30 According to Gleason, the Dodgers advised him to hire a lawyer to appeal the decision. “Listening to this advice turned out to be very foolish on my part,” he later said. “I put my entire stock in their wisdom, and I made a mistake.”31 When he received his draft notice in April of 1967, he went to basic training and advanced infantry training before shipping out to Vietnam in December of 1967 during the height of the Vietnam War.

In March of 1968, Gleason received the Bronze Star for his bravery during a search-and-destroy mission, when he transported two wounded soldiers to safety. “I couldn’t help feeling that I really needed to be at spring training instead of sitting in the God-forsaken land of Vietnam,” he recalled about his early months in the war. “Here I was dodging bullets each day, fighting a war that half our nation opposed.”32 Buzzie Bavasi, general manager of the Dodgers and a World War II veteran, regularly wrote to him while he was in Vietnam, to update him on the Dodgers. “Everything Buzzie sent me reminded me I had a future,” Gleason recalled. “I thought, this will be a springboard for me, because I was in good [physical] shape over in Vietnam. As soon as I get home, I’ll be ready to play.”33

Gleason’s hopes to return to the Dodgers were derailed on July 24, 1968, when he was leading a patrol through the jungle and a Viet Cong mine exploded in his path. “Seeing the blood from my wounded wrist, I quickly made a tourniquet to stop the blood flow,” Gleason said of his reaction to the bomb blast. “At first, I didn’t feel the shrapnel in my lower leg. The adrenaline pumping through my body and instinct to survive helped overcome the pain.”34 Gleason, along with several wounded soldiers in his platoon and three men killed in action, was evacuated by helicopter to their base camp. He was soon transported to a military hospital in Saigon and then transferred to a hospital in Osaka, Japan.35 Left behind in his foot locker at base camp was Gleason’s cherished 1963 World Series ring, which was missing (stolen) when his locker was returned to him stateside.36

Roy Gleason received the Army Commendation Medal for his heroism in the evacuation of his wounded soldiers and also the Purple Heart for being wounded himself in combat. “Although the ceremony wasn’t very extravagant, I knew that my sacrifice had been recognized,” he later said. “I was only worried that the sacrifice would include my baseball career.”37

An Associated Press article published in August of 1968 told Gleason’s story to millions of Americans across the country. “Charley’s a darn good fighter,” he told writer John Roderick from his hospital bed in Japan, referring to the Viet Cong. “But not as strong as he was. He’s a pretty bad shot, too. Look how he missed me.”38 By September Gleason was convalescing at Letterman Army Hospital in San Francisco. “Shrapnel from the blast ripped open his left calf, put a hole in his left wrist, and damaged his right arm,” Michael Leahy wrote of Gleason’s wounds in his book The Last Innocents. “He discovered that his calf wound had robbed him of virtually all his speed. The wrist wound had the effect of leaving his left index finger numb, so he no longer could grip a bat quite right.”39

Despite the obstacles, Gleason actively pursued physical therapy, telling the medical staff that he “was on a mission to return to baseball.”40 However, because he had lost 40 pounds from his previous 235-pound frame, there were serious questions about his return to baseball after being away from the sport for two years. Discharged from the Army in January of 1969, he went to spring training with the Dodgers. Unfortunately for Gleason, Bavasi, his top supporter while in Vietnam, had left the Dodgers to become president of the expansion San Diego Padres.

Gleason was a big story at 1969 spring training, as Los Angeles sportswriters wrote lengthy pieces about the Vietnam War hero. John Wiebusch of the Los Angeles Times wrote an eloquent story about Gleason’s time in Vietnam and the resulting “purple-red gash on his left wrist” and “lumps on his calf where eight pieces of shrapnel are imbedded in the flesh.”41 Bob Hunter of the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner penned a full-page article in The Sporting News, noting how Gleason joked, “I guess I got the lead out” when doctors removed some of the metal shell fragments from his leg.42 Everyone, though, knew that he was a long shot to play again for the Dodgers.

In reality Gleason, nearing 26 years old and eight years removed from his bonus-baby signing, was auditioning for a spot with the Triple-A Spokane farm club, which held his contract when he was drafted. Spokane optioned him to the lower minors at the end of spring training.43 Following subpar stints with Double-A Albuquerque (.121 average in 27 games) and Single-A Bakersfield (.209 average in 74 games), his career with the Dodgers ended in December of 1969 when the California Angels selected him in the minor-league draft.44

The Angels played in a new ballpark in Anaheim, just a few miles from Roy’s hometown of Garden Grove. While the Angels didn’t have a spot for him in their minor-league system for the 1970 season, the ballclub did arrange for him to play with the Jalisco club in the Mexican League, which lacked affiliation with major-league farm systems. Gleason’s baseball career ended in January of 1971 when he was severely injured in a truck accident while working an offseason job in the mountains of Northern California.45

Gleason finished with a lifetime batting of .223 in six minor-league seasons, in addition to the 1.000 batting average he compiled during his abbreviated tenure in the major leagues. “I just wish I’d had a real chance at baseball. Being drafted killed my career,” he later mused. “Nothing was going to be the same after that. But the draft and Vietnam did things like that to all kinds of people. That year [1968] I got hurt was a bad time for a lot of guys.”46 In his post-baseball life, Roy was married and divorced twice, had two sons (Troy and Kaile) in his second marriage, and settled into working as a car salesman at Hardin Honda in Anaheim after trying out a number of different occupations, including furniture mover and bartender.47

In 2001, more than 30 years after leaving professional baseball, Gleason’s baseball career finally turned positive when he met Wally Wasinack, a customer at Hardin Honda.48 While they easily conversed about Roy’s baseball life, Wasinack was more intrigued by Roy’s military service and embarked on a mission to get Roy more recognized. He connected with Mark Langill, the publications director for the Dodgers, who arranged for Gleason to visit Dodger Stadium on July 17, 2003. As part of a tour of the ballpark, Gleason visited the wall that is inscribed with the names of all former Dodgers players. After locating his name there, he remarked, “I’d rather be on this wall than the other one,” referring to the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., that honors those killed in action during that war.49

On September 20, 2003, the Dodgers honored Gleason in a pregame ceremony at Dodger Stadium to celebrate the 40th anniversary of his lone major-league base hit. After the ballclub showed a two-minute video of him on the scoreboard, narrated by legendary announcer Vin Scully, he threw out the ceremonial first pitch. Manager Jim Tracy and the Dodgers players then trotted out to the mound to surprise him with a box containing a replica of his 1963 World Series ring that he had lost in Vietnam.

“I was in shock when he handed me the World Series ring, and it remains one of the most incredible instances of my life,” he wrote in his 2005 book Lost in the Sun: Roy Gleason’s Odyssey from the Outfield to the Battlefield, co-written with Wasinack. “I felt like I was 20 years old again, and the only regret I have now is that it couldn’t continue.” During the playing of the National Anthem, he recalled that “emotion overwhelmed me, as I realized that the Dodgers and the fans were recognizing all those who have gone to war. I was merely a figurehead for veterans from all wars, especially the thousands who perished in the jungles of Vietnam.”50

The media soon labeled Gleason as the only professional baseball player to serve in Vietnam after having played at the major-league level.51 However, that aspect of his military service was not the recognition Gleason sought. The ring ceremony at Dodger Stadium inspired him to become a public proponent for all veterans, not just ballplayers and not just those of the Vietnam era.

Following his participation in a Memorial Day ceremony held by the San Diego Padres in 2006, Gleason began pitching major-league clubs to adopt his Operation ERA concept (Earned Recognition and Appreciation), to honor veterans by conducting ballpark programs.52 His mission helped to spark Major League Baseball to create the Welcome Back Veterans initiative announced in June of 2008. At the games on Memorial Day in 2009, all major-league clubs first wore special caps to honor veterans. Gleason was later recognized for his efforts on behalf of veterans during a pregame ceremony at Game Two of the 2017 World Series.53

In a 2015 interview, the 72-year-old Gleason was sanguine about his baseball experience as a one-hit wonder. “The only way I can look at it is that I was blessed to be able to have the tools to get there in the first place,” he told Sam Gardner of Fox Sports. “Every kid dreams about playing in the major leagues, and I got that chance. It was only one at-bat, but I was there. How many guys in America today wish they could have had just one at-bat in the majors? So I was fortunate. It wasn’t meant to be, and I’m happy where I’m at now, and that’s all that counts.”54

Last revised: June 1, 2021

Notes

1 The Sporting News Baseball Players Contract Cards Collection, Roy Gleason.

2 Roy Gleason, Lost in the Sun: Roy Gleason’s Odyssey from the Outfield to the Battlefield (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2005), 1, 31.

3 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, 49.

4 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, 57, 69.

5 “Dodger Rookies Appear,” San Bernardino (California) Sun, July 1, 1960: 28.

6 “Dodgers Give Prep $75,000,” Los Angeles Times, June 17, 1961: 17.

7 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, 77.

8 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, 78-79.

9 Allen Lewis, “Baseball Bonus Spree Is ‘Suicide,’ Phils’ Quinn Says,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 20, 1961: 35.

10 Bob Hunter, “Moeller Rated Tops in Dodger Kiddies’ Class,” The Sporting News, November 29, 1961: 15; “Taking Shortcut in Climb Up Dodger Ladder,” The Sporting News, December 20, 1961: 4.

11 Frank Finch, “Reiser Pins No. 1 Tag on ’62 Dodgers’ Kids,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1962: 4.

12 “Dodgers Juggle Farm Hands to Set Up 40-Man Roster,” Palm Springs (California) Desert Sun, October 20, 1961: 8; Dodgers 40-man roster, The Sporting News, January 10, 1962: 11.

13 Bob Hunter, “‘Wide Open,’ Smokey Says in Sizeup of ’62 NL Race,” The Sporting News, February 7, 1962: 17.

14 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, 141.

15 “Braves Tackle Dodger Rookies,” San Bernardino Sun, July 4, 1961: 9.

16 Keith Sharon, “A Rookie at Peace: The Only Major-League Ballplayer Sent to Vietnam Got Back One Thing He Lost,” Orange County Register (Anaheim, California), March 1, 2006: 1.

17 Michael Arkush, “Five-Star Ball Player Roy Gleason: The Only Major Leaguer Who Served in Vietnam,” The VA Veteran, May/June 2004: 27.

18 Sam Gardner, “One & Done: Roy Gleason Only MLB Player Wounded in Vietnam,” Fox Sports website, August 11, 2015. foxsports.com/mlb/story/one-done-roy-gleason-was-only-mlb-player-wounded-in-vietnam-war-081115.

19 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, 120.

20 “Splitting Swag,” The Sporting News, October 26, 1963: 6.

21 Sharon, “A Rookie at Peace: The Only Major-League Ballplayer Sent to Vietnam Got Back One Thing He Lost.”

22 “Deals of the Week,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1964: 21; Dodgers 40-man roster, The Sporting News, January 23, 1965: 21.

23 “Coast Loop Crews,” The Sporting News, May 1, 1965: 38.

24 “Deals of the Week,” The Sporting News, May 22, 1965: 34.

25 “Salem Conversion Project,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1965: 39.

26 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, 150.

27 “Induction Statistics,” Selective Service System website, sss.gov/About/History-And-Records/Induction-Statistics; John Finney, “New Husbands Face Draft as Exemption Is Removed,” New York Times, August 27, 1965: 1.

28 John Herbers, “Congress Panel Is Studying Draft,” New York Times, December 8, 1966: 1; B. Drummond Ayres, “Reserves Told to Enlist Men as Names Come Up,” New York Times, December 23, 1966: 11. The congressional report was issued in April of 1967 (“360 Pros Reported Exempt from Draft,” New York Times, April 8, 1967: S23).

29 Robert Lipsyte, “Murcer, Yanks, Called by Army; Shortstop Is Lost for 2 Years,” New York Times, February 25, 1967: 32.

30 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, 150.

31 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, 151.

32 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, 174-176.

33 Michael Leahy, The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers (New York: Harper Collins, 2016), 415.

34 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, 8.

35 “Bonus Baby Hurt in Vietnam,” Los Angeles Times, July 31, 1968: 38.

36 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, 222.

37 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, 184-185.

38 John Roderick, “Roy Gleason: Charley Is a Darn Good Fighter,” Asheville (North Carolina) Citizen-Times, August 4, 1968: 23.

39 Leahy, The Last Innocents, 416.

40 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, 185.

41 John Wiebusch, “Gleason: War-Wounded Dodger Starts Comeback at Vero Beach,” Los Angeles Times, February 28, 1969: 2.

42 Bob Hunter, “A Vietnam Hero Prizes Ted’s Letter,” The Sporting News, March 22, 1969: 12.

43 “Deals of the Week,” The Sporting News, April 26, 1969: 28.

44 “Minors Cut Back in Draft Selections,” The Sporting News, December 13, 1969: 34.

45 Bill Plaschke, “At Ease, At Last,” Los Angeles Times, September 19, 2003: 33.

46 Leahy, The Last Innocents, 416.

47 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, ix, 213-216.

48 John Hunneman, “Roy Gleason, the Only Ball Player Wounded in Vietnam, Urges Baseball to Honor His Fellow Vets,” San Diego Union-Tribune, August 12, 2007.

49 Plaschke, “At Ease, At Last.”

50 Gleason, Lost in the Sun, 238.

51 Sharon, “A Rookie at Peace: The Only Major-League Ballplayer Sent to Vietnam Got Back One Thing He Lost”; Hunneman, “Roy Gleason, the Only Ball Player Wounded in Vietnam”; Arkush, “Roy Gleason: The Only Major Leaguer Who Served in Vietnam.”

52 Hunneman, “Roy Gleason, the Only Ball Player Wounded in Vietnam.”

53 Alyson Footer, “Vietnam Veterans Honored Before Game 2,” MLB.com, October 25, 2017.

54 Gardner, “One & Done: Roy Gleason Only MLB Player Wounded in Vietnam.”

Full Name

Roy William Gleason

Born

April 9, 1943 at Melrose Park, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.