Roy Parmelee

When Bud Parmelee was pitching for Double-A Columbus in 1932, his good-luck charm was a blind boy, Charlie Medick. “He would root for me and pray for me when I pitched and I never lost a game there.” It worked: Parmelee went 14-1 for Columbus with a 2.80 ERA.

When Bud Parmelee was pitching for Double-A Columbus in 1932, his good-luck charm was a blind boy, Charlie Medick. “He would root for me and pray for me when I pitched and I never lost a game there.” It worked: Parmelee went 14-1 for Columbus with a 2.80 ERA.

Two years later, Parmelee was with the New York Giants, feeling weak after an appendectomy. Charlie and his father came to a Giants game in Pittsburgh. “Bud, do me a favor,” the boy said. “Pitch a no-hitter today.”

Parmelee almost did. He didn’t allow a hit until the eighth inning. After the game he apologized to Charlie for failing to deliver. “Bud, you know when I talked to you this morning at the hotel, I didn’t think you had confidence,” Charlie told him, “so I asked you to pitch a no-hitter. I thought if I asked you to do that, you would try very hard to do it, and with my prayers you might make it, or at least win the ball game, which you did. And we can still say that you’ve never lost a game when I’ve been in the stands.”1

Four teams pinned their hopes on Parmelee’s electric right arm. All were disappointed, but none was as forgiving as young Charlie. Giants catcher Gus Mancuso saw the best and worst: “Parmelee had as much stuff as any four or five pitchers put together, but he didn’t know where it was going.”2

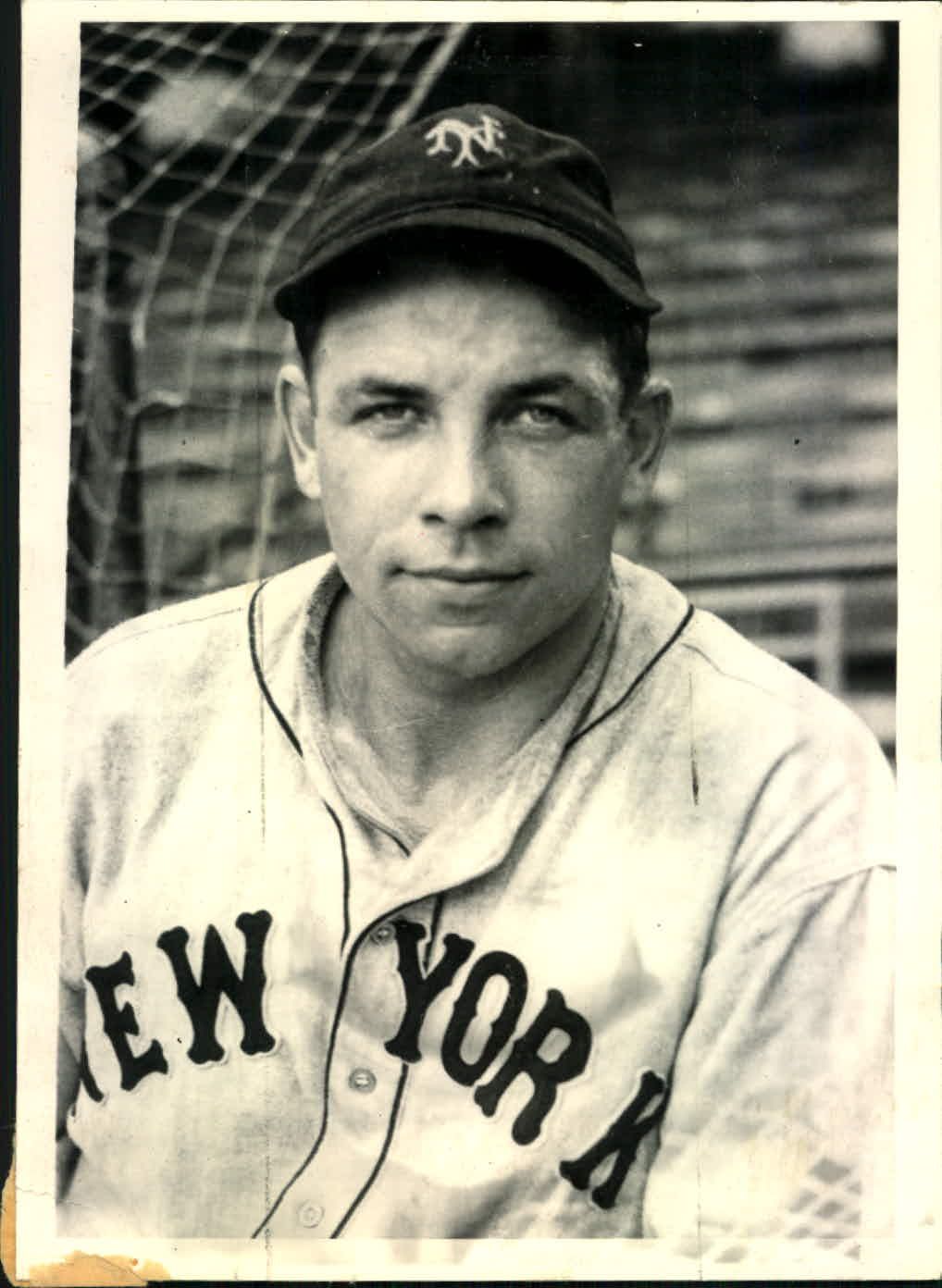

With a near-sidearm delivery, Parmelee threw a fearsome sailing fastball that veered sharply like a slider or cutter. And he looked like a pitcher: 6-feet-1, around 200 pounds, with broad shoulders and thick forearms. When New York Daily News writer Jimmy Powers started calling him “Tarzan,” Parmelee thought it was a tribute to his muscular build, but Powers told him it was because of his wildness: “Every time you pitch you seem to be out on a limb.”3

Too often he sawed the limb off, walking batters in bunches — six, seven, eight in a game. James Isaminger of the Philadelphia Inquirer said Parmelee “walked everybody in baseball except Judge Landis.”4 In addition, he led the National League in hit batsmen four times and in wild pitches twice.

Leroy Earl Parmelee was born in Lambertville, Michigan, on April 25, 1907, the son of Olin Parmelee, a physician, and the former Edith Kinney. When Leroy showed interest in following his father’s profession, Dr. Parmelee began taking him along on his rounds. “As I grew older, he took me on every gruesome, pitiable and sordid case he attended. It would sicken you if I told you the sights I saw.” The doc was determined to discourage his son’s ambition because the life of a country doctor was too hard.5

As a boy, Leroy showed a strong arm, but was not allowed to pitch in sandlot games. “They were afraid I’d kill somebody.”6 He dropped out of Michigan State Normal College (now Eastern Michigan University) after a year and took a factory job in Toledo, pitching in semipro ball on the side. Toledo Mud Hens manager Casey Stengel was the first to be captivated by his live arm, and signed him to a professional contract.

Joining the Mud Hens in 1927, Parmelee was a raw, unfinished product. Stengel had to teach him a pickoff move. The first time he tried it in a game, he hit the runner in the chest. The first baseman picked up the ball and tagged the man lying stunned on the ground. “You have it down perfect,” Stengel said.7

Toledo farmed him out to lower levels for two years. He stuck with the Mud Hens in 1929 and picked up the nickname “Bud” from a local softball star named Bud Parmelee. Stengel called him “Doc” because of his father’s profession and “Big Bess” because the manager thought he walked like a girl.8 Despite Parmelee’s unimpressive record at the highest minor-league level — 12-14, 4.77 — Stengel convinced his mentor, Giants manager John McGraw, to pay a reported $50,000 for the pitcher’s potential.

“McGraw was a great one,” Parmelee said, “but he was too rough for me.” He joined the Giants in September 1929 just in time to witness one of the manager’s clubhouse tirades. McGraw chewed out several players before he got around to the rookie pitcher who had yet to appear in a game. “And you, Parmelee, I don’t know how you expect to be a big leaguer — you eat too much.”9

The 22-year-old pitched twice for the Giants late in the 1929 season and recorded his first major-league victory, but gave up seven earned runs in seven innings. For the next three years he bobbed up and down between the Polo Grounds and Double-A ball, never able to satisfy McGraw. In those brief trials he walked 73 batters in 106 innings and pitched to a 5.43 ERA. One writer said he “couldn’t make his speed behave.”10

After the 1932 season Parmelee married a high school classmate, Ortha Smith. By then the Giants had a new manager. McGraw retired in June 1932, and turned the team over to first baseman Bill Terry. After a sixth-place finish, Terry overhauled the roster. He inherited just two dependable starting pitchers, Carl Hubbell and Fred Fitzsimmons. He announced that the erratic Parmelee and 22-year-old sinkerballer Hal Schumacher would round out the rotation. He acquired Gus Mancuso, a crack defensive catcher, to guide them and put the National League’s best defense behind them.

Parmelee started his 1933 season against the Phillies. Leading off the third inning, Philadelphia’s Neal Finn smoked a hard grounder that skidded between the legs of third baseman Johnny Vergez. “It could have been called either a hit or an error, but it went in the books as a double,” Parmelee said. It was the Phillies’ only hit. “Some of the writers later apologized to me for the way it was scored.”11 Finn came around to score on a wild pitch for the Phillies’ only run as the Giants won, 3-1.

Parmelee won four consecutive decisions, then lost for the first time when he walked six in eight innings. In a June start he walked five in the first inning and was charged with five runs without giving up a hit. But Terry kept him in the rotation and built up his confidence.

In addition to his wildness on the mound, Parmelee had some wild nights — not because he was a party animal, but because he was a sleepwalker. Terry assigned him to room with backup catcher Paul Richards, who had the same affliction. It’s not clear how they were supposed to stop each other from wandering, but at least they weren’t keeping two other roommates awake.

Richards, who became a respected manager with a knack for developing pitchers, taught Parmelee to throw a sinking fastball. But when he told Terry about the new pitch, the manager responded, “Leave him alone. He’s doing fine.”12 Terry, a former pitcher, remembered minor league managers trying to change him — and only succeeding in confusing him. “If he can win games for us,” Terry said, “I don’t care if he pitches standing on his ear.”13

Parmelee was winning games, and so were the Giants. On July 2 New York was in first place, 3½ games ahead of the Cardinals, when the two teams met in a Sunday doubleheader at the Polo Grounds. Hubbell and St. Louis’s Tex Carleton put zeroes on the scoreboard for 16 innings before Carleton left for a pinch-hitter. Hubbell kept going. Even with the winning run on second in the 18th, Terry didn’t pinch-hit for his pitcher. After Hubbell grounded into a force-out, the next batter, Hughie Critz, ended the four-hour marathon with an RBI single.

There was another game to play, matching Parmelee against Dizzy Dean in a steady drizzle and fading daylight. Dean, pitching on one day’s rest, yielded a homer to Vergez in the fourth. Parmelee buzzed through the opposing lineup, striking out 13 nervous Cardinals. “He was wild enough in the daylight,” Giants outfielder Joe Moore said, “but in that kind of weather — well, you could get killed up there.”14 The Giants won, again by 1-0.

“Hubbell did not walk a man in the 18 innings, and even harder to believe, I didn’t walk a man in 9 innings!” Parmelee recalled.15 One observer remarked that he could only find the plate when he couldn’t see it. It was Parmelee’s third complete game without a base on balls; he did it only once more for the rest of his career.

A dramatic improvement in control was the key to Parmelee’s breakout season. He walked only 3.2 batters per nine innings, although he hit 14 men (breaking the hands of two) and threw 14 wild pitches. He finished at 13-8, 3.17. His strikeout rate, 5.4 per nine, was second in the league behind Dean.

The Giants won the pennant with excellent pitching and defense. Hubbell’s 1.66 ERA was the lowest since the Deadball Era, and his 23-12 record earned him the MVP award. Schumacher added 19 victories and Fitzsimmons 16, both with ERAs under 3.00. Parmelee was clearly the #4 starter. He sat throughout the World Series, never throwing a pitch, as New York defeated Washington in five games.

On top of his wildness and sleepwalking, Parmelee had a reputation as a hypochondriac. For a while he was convinced he had heart trouble and frequently checked his pulse. He complained of toothaches that dentists couldn’t find. In the spring of 1934 it was abdominal pain. This time he wasn’t making it up; he underwent an emergency appendectomy and missed more than two months.

Parmelee returned to post a 10-6 record in the second half. A strong September brought his ERA down to 3.42. The Giants lost the pennant to St. Louis when archrival Brooklyn beat them on the last two days of the season.

In 1935 New York was fighting for first place again with St. Louis and the Chicago Cubs. The Giants and Cardinals met in a doubleheader on a typical July afternoon in St. Louis: 94 degrees with brutal humidity. Schumacher, the game-one starter, passed out in the sixth inning and woke up in the clubhouse packed in ice, near death from heat prostration. The Giants won, 3-1, then their bats got as hot as the weather in game two. They piled up a 12-0 lead after four innings.

Parmelee didn’t allow a run through the seventh, but he was hardly cruising. He gave up nine hits, walked five, and hit a batter. “Get the ball over, Roy,” the exhausted catcher, Harry Danning, begged. “Please get the ball over.”16 Parmelee staggered to a 13-2 victory, with Danning sweating through every inning of both games.

As the Giants slipped to third place, Parmelee led the league in walks and hit batters in a career-high 226 innings. He finished 14-10 despite a 4.22 ERA, but his strikeout rate dropped to just over three per nine innings and his home run rate doubled, signs of diminished stuff.

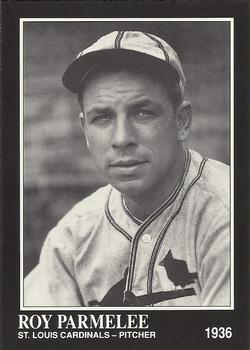

After the season Terry traded Parmelee to the Cardinals, with first baseman Phil Weintraub and cash, for Burgess Whitehead, the second baseman the Giants needed. Dizzy Dean welcomed the new addition to the starting rotation, along with himself and his brother. He predicted a big year for “Paul and me and Parmelee.”17

The new Cardinal faced his old teammates for the first time on April 29, 1936, in St. Louis. Parmelee and Hubbell pitched shutout ball through 11 innings. Parmelee walked the leadoff batter in the 12th and he came around to score, but St. Louis tied it in the bottom half.

The new Cardinal faced his old teammates for the first time on April 29, 1936, in St. Louis. Parmelee and Hubbell pitched shutout ball through 11 innings. Parmelee walked the leadoff batter in the 12th and he came around to score, but St. Louis tied it in the bottom half.

The two pitchers slogged onward into the 17th. In the Cardinals’ half, a double and an intentional walk brought Parmelee to the plate with one out. He slapped a double-play grounder to shortstop Dick Bartell, who fumbled it to load the bases. In the grandstand, St. Louis restaurant owner Henry Hoffmann dropped dead of a heart attack. Then Terry Moore grounded to third baseman Travis Jackson, but Jackson’s throw to the plate was wide as the winning run scored. It was one of the best performances of Parmelee’s up-and-down career: six hits and just four walks in 17 innings.

The Giants went on to win the pennant, with St. Louis tied for second. Parmelee was a disappointment. He walked 107 in 221 innings, and hit 10, finishing 11-11, 4.56. After the season the Cardinals shipped him to the Cubs as part of a deal for right-hander Lon Warneke.

The trade put him into another pennant race against the Giants. The Cubs held first place for 2½ months, but faded down the stretch. Parmelee was no help; shoulder trouble limited him to just two appearances in September as his team finished three games behind New York. His ERA swelled to 5.l3 with a 7-8 record. To make matters worse, Warneke won 18 for the Cardinals.

At 30, Parmelee had disappointed three clubs in three years. The Cubs traded him to Double-A Minneapolis, where his troubles continued in 1938. He walked six batters per nine innings and set an American Association record with 22 wild pitches. He managed a 17-13 record, and one major-league team was desperate enough to give him another shot.

Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics had settled at or near the bottom of the American League after he sold his stars to keep the franchise afloat during the Depression. Mack drafted Parmelee and put him in the starting rotation in 1939. “That may have been my most frustrating year in baseball,” Parmelee remembered.18

It was ugly: 35 walks in 44⅔ innings, a 6.45 ERA, and a 1-6 record. His sole victory came against the St. Louis Browns, the only team worse than the Athletics. By June Mack had seen more than enough and dumped him to the minors.

Parmelee hung on for three more years in Double-A ball, winding up back where he had started, in Toledo, in 1941. He retired at 34 to take a job in a defense plant.

After the war he went to work as a sales representative for the Automobile Club of Michigan, and managed the club’s office in Monroe until he retired in 1971. His wife, Ortha, taught history at the local high school. They had a son, Roy, and daughters Jan and Annalee.

Late in his life Parmelee was hobbled by arthritis and contracted lung disease. He died at 74 on August 31, 1981.

Parmelee never expressed bitterness about his baseball career. He even saw a silver lining in his disastrous final season; it gave him a chance to pitch for Connie Mack. He thought he was the only man to play for Mack, McGraw, and Stengel.

“I was my own worst enemy with the wildness,” he said. “They used to say I wasn’t beaten by the opposition very often, but by myself.”19

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Notes

1 Eugene Murdock, “Some Called Him Tarzan,” Baseball Research Journal 10 (SABR, 1981). http://research.sabr.org/journals/some-called-him-tarzan. It happened on August 17, 1934. When Parmelee told the story more than 40 years later, he got a few details wrong, but his memory was precise enough that it was easy to find the game.

2 Gus Mancuso interview by Clark Nealon, c. 1980, in the collection of the Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Houston, Texas.

3 Murdock, “Some Called Him Tarzan.”

4 James C. Isaminger, “Knott Holds A’s to 3 Hits, White Sox Romp in 12-1 Win,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 6, 1939: 23.

5 C.E. Parker, “Story of a Country Doctor,” New York World-Telegram, July 20, 1933, in Parmelee’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

6 Murdock, “Some Called Him Tarzan.”

7 Bill Brenton, “The Press Box,” Monroe (Michigan) Evening News, October 2, 1975: 1-B.

8 Ibid.

9 Murdock, “Some Called Him Tarzan.”

10 “Parmelee Returns to Old Loop for Control,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 14, 1932: 24.

11 Murdock, “Some Called Him Tarzan.”

12 Donald Honig, The Man in the Dugout (Chicago: Follett, 1977), 129.

13 John Drebinger, “Terry Pleased Over the Outlook for Revamped Giants This Season,” New York Times, February 3, 1933: 22.

14 Robert Gregory, Diz (New York: Viking, 1992), 104.

15 Murdock, “Some Called Him Tarzan.”

16 Peter Williams, When the Giants Were Giants (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin, 1994), 187-188.

17 Dick Farrington, “Fanning with Farrington,” The Sporting News, December 19, 1935: 4.

18 Murdock, “Some Called Him Tarzan.”

19 Ibid.

Full Name

Leroy Earl Parmelee

Born

April 25, 1907 at Lambertville, MI (USA)

Died

August 31, 1981 at Monroe, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.