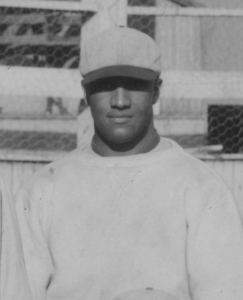

Rudolph Ash

Rudolph Ash played in eight league games for the 1920 NNL champion Chicago American Giants, though he also may have participated in a few exhibition games. Subsequently, it took another three years before Ash’s name again was mentioned in association with baseball in the press. At that time, he was enrolled in the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where he was – in one sense – a college precursor to Jackie Robinson.

Rudolph Ash played in eight league games for the 1920 NNL champion Chicago American Giants, though he also may have participated in a few exhibition games. Subsequently, it took another three years before Ash’s name again was mentioned in association with baseball in the press. At that time, he was enrolled in the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where he was – in one sense – a college precursor to Jackie Robinson.

As it turned out, Ash’s collegiate baseball career lasted only slightly longer than his stint with the American Giants. After he moved from his native state of Indiana to New York City in 1926, Ash had one last cup of coffee in the Eastern Colored League. Ed Bolden signed Ash to his Hilldale club,1 but he played in only one league game before being released. He caught on with the Newark Stars in June and played in three games before an unexpected circumstance ended his season and his pursuit of a career as a professional baseball player.

After Ash married in 1927, he found employment off the diamond, although he also played semipro ball for a few more years. In 1942, Ash’s coach at Michigan, Ray Fisher, named him as a member of his all-time Michigan baseball team.2 Fisher had pitched to a career 100-94 record with a 2.82 ERA for the New York Yankees (1910-17) and Cincinnati Reds (1919-20). As of 2021, he was still Michigan’s winningest head coach, having led his teams to a 636-295-9 record and one national championship between 1921 and 1958.3

The fact that Fisher bestowed such high praise on an athlete who had participated in his program for only one year was remarkable, but it also poses the question why Ash did not have a successful professional career. Perhaps Rube Foster, the American Giants’ Hall of Fame owner, was correct when, upon firing drunken former college pitcher Tom Williams in 1918, he asserted that “in all his experience in baseball this sort of players [college players] are the hardest kind to keep straight in the world.”4 Considering why Ash left Michigan, it is entirely possible that Foster’s comment could be applied to him as well.

Ash’s family background and college years are perhaps of more historical interest than his stunted professional baseball career. Regarding his ancestry, he was descended from one of the first Black families to settle in South Bend, Indiana. Ash’s maternal great-grandfather, Pharaoh Powell, was a freed slave from South Carolina who brought his wife, Rebecca, and their children to the Hoosier State circa 1853.5 The fact that Powell settled in Indiana at that time put his family and the residents of South Bend who allowed him to stay there in violation of Article 13 of Indiana’s 1851 state constitution, which read:

“Section 1: No negro or mulatto shall come into or settle in the State, after the adoption of this Constitution.

“Section 2: All contracts made with any Negro or Mulatto coming into the State, contrary to the provisions of the foregoing section, shall be void; and any person who shall employ such Negro or Mulatto, or otherwise encourage him to remain in the State, shall be fined in any sum not less than ten dollars, nor more than five hundred dollars.”6

The law also stipulated that all fines collected for violations of Article 13 would be set aside to send the “negro or mulatto” in question to Liberia, if said person(s) were willing to emigrate there.

Despite Indiana’s official hard-line stance against Black settlers, the city of South Bend proved to be a hospitable location, and no one is known to have been fined under Article 13. According to a local historian, “Beginning in 1858, Pharaoh Powell bought several acres of land to the southwest of downtown South Bend, in Union Township, along Main Street and elsewhere in the county.”7 In addition to becoming a prominent family in the area, three of the Powells’ sons enlisted in the Union Army to fight in the Civil War.8

Pharaoh and Rebecca’s daughter, Nancy Powell, married William Henderson on August 5, 1879. Henderson was from La Porte County, Indiana, and had also served in the Civil War. At a banquet given in his honor in October 1934, he recollected, “My ancestors were freed slaves. When about 13 years of age, I entered the civil war [sic] near its close as a handy boy to Colonel Milroy, of the Ninth Indiana Infantry. Peace was declared before I saw a battle.”9 William later moved to South Bend, where he met Nancy.

William and Nancy Henderson had one child, a daughter named Cora Bell, who was born on January 8, 1881. On February 21, 1899, Cora Bell Henderson married Thaddeus Ash, who was from Michigan, and the couple resided with the Hendersons. Rudolph Thaddeus Ash, the future baseball player, was born on November 2, 1899, in South Bend.

Although William Henderson provided a roof over his daughter and son-in-law’s heads, he was not so well off that he could support them financially. Henderson worked as a waiter at the Grand Central Hotel while Thaddeus Ash held a job as a porter and Cora found work at the local YMCA. The family’s hardscrabble existence is hinted at by how young Rudolph Ash referred to himself in his 1906 letter to Santa Claus, which was printed in the South Bend Tribune on December 15. Seven-year-old Rudolph wrote (with all misspellings and grammar errors left intact by the newspaper):

“Dear Santa Clause – I want a new suit and a cap and a pair shoes and lagerns. Please send also a large engine with 5 cars and a coal car. I want a Xmas book with nice Xmas pieces in it. I would like to have all these things hung on a tree in my parlor good by Santa Clause please make some little poor boy happy thanks for every thing I am Rudolph Ash 422 S Main St South Bend Ind.”10

His childhood interest in railroads cars must have had a lifelong appeal for Ash, since he eventually found a career with the Pennsylvania Railroad and worked for the company long enough to receive a pension.

Less than a year after Christmas 1906, life became harsher for Ash’s family due to his father’s excessive drinking. On July 11, 1907, Thaddeus Ash pleaded guilty to charges of assault and battery upon his wife and father-in-law. He was ordered to pay $20 (a $5 fine and $15 for court costs) and received a 30-day jail sentence. However, “upon his promise to the court as well as his father-in-law to refrain from drinking in the future, he was released upon suspended sentence by paying the fine and costs.”11

Thaddeus soon reneged on his promise and he and Cora separated on August 9, 1907. Thaddeus moved back to Kalamazoo, Michigan, and young Rudolph continued to live with his mother and his grandparents in South Bend. Thaddeus kept in touch with Rudolph and even listed him as his contact on his World War I draft registration card in 1918. It appears that Cora wanted to give her husband every chance to make good; however, on February 23, 1917, she finally sued for divorce, “making a general charge of cruel and inhuman treatment.”12

According to the US Census, South Bend had seen a 49.1 percent population growth between 1900 and 1910, and the crime that often accompanies such growth affected the Henderson-Ash household in 1911. A thief who had become known as a “gentleman burglar” had been working the neighborhood and continually eluded the police. On October 9 he targeted the Henderson house, but he picked the wrong time as its occupants were still awake. Cora “screamed while her father stood by the rear window with a club in hand to receive the midnight visitor, but he was frightened away.”13

Although Ash and his family had their struggles, he also experienced some benefits of growing up in South Bend. At a time when most schools throughout America were still segregated, Ash was able to attend South Bend High School, the only high school in town, and graduated in 1918.14 In September Ash registered for the draft and indicated that he was working at Notre Dame University and was preparing to attend college.

As the United States continued to ramp up its war efforts since having become involved in World War I the previous year, Ash joined the Student Army Training Corps at Indiana University in Bloomington. The Corps existed on many campuses and had been “created to keep students in college while preparing to fight the war.”15 At Indiana University it “included four companies and well over 1,000 men. Members wore uniforms, were paid $30 a month and lived in barracks that were converted fraternity houses.”16

Ash was one of “only a handful” of Black men at Indiana University, who “drill[ed] with white classmates and liv[ed] separately in Barracks No. 7.”17 All branches of the US military maintained racially segregated units at that time; thus, the separate living quarters at IU were no surprise. However, by drilling with their White classmates, Ash and his Black classmates had become trailblazers. John Summerlot, the director of the university’s Veterans Support Services, asserted, “I would argue the first racially integrated Army unit was the SATC. And it may have been just at IU. I’ve yet to find any other integrated SATC units during World War I.”18

When the 1918 flu pandemic reached Bloomington, Indiana’s State Board of Health closed the IU campus from October 10 until November 4. As a result, “SATC members were confined to their barracks, and other students were sent home. … By the end of December 1918, the SATC members had been discharged from the military.”19 Ash returned home to South Bend in time for Christmas. Before the next academic year, he visited his father in Kalamazoo and then announced that he was going to attend the University of Michigan.20

Surprisingly, since Ash had not spent any time in the limelight, his life had been well documented to this point. South Bend directories and the 1920 US Census list Ash as a university student, presumably at the University of Michigan, although he was not yet a member of the Wolverines’ baseball team. He did, however, have a brief stint with Chicago American Giants in the summer of 1920.

Ash must have played baseball somewhere to be discovered and signed by Foster, but when and where are unknown. Ash was so unfamiliar to the Chicago press that he was listed in box scores as “Rudolph” more often than by his surname, Ash. Professional baseball may have been just a summer diversion for Ash as he received most of his playing time in July. He manned left field in a series against the St. Louis Giants from July 11 to 13 at Schorling Park in Chicago; the American Giants triumphed by scores of 5-2, 4-2, and 7-6. Ash, listed as “Rudolph” for all three contests, contributed two hits in the middle game and scored a run in the July 13 contest.21

On July 19 Ash – now listed in the box score by his surname – played right field in a 3-1 triumph over the Dayton Marcos at Schorling Park.22 He had one hit but did not score a run. Ash participated only in games in Chicago, a city that he and his family often visited. He did not distinguish himself during his brief time with the American Giants; he batted .208 (5-for-24), scored three runs, and had two RBIs in eight NNL games.

In October, it was reported that Ash had “returned to Ann Arbor, Mich., where he [was to] resume his law studies at the University of Michigan.”23 At this point in his life, Ash did not yet combine academic and baseball pursuits. In late May of 1921, after the spring semester ended, it was reported that “Jess Elster and his new gang of Colored Athletics” from Grand Rapids, Michigan, had “obtained Rudolph Ash of Ann Arbor, an infielder, who should be a big attraction during the season.”24 No further mention of Ash is found in articles about the Colored Athletics’ games; he may not have reported to Elster’s team after all.

After a one-year baseball hiatus, Ash popped up again in 1923. The Chicago Defender claimed, “Rudolph Ash of South Bend, Ind., is the first student of Color to ever play on the Michigan university baseball team.”25 Since the Defenderhad not been founded until 1905, perhaps it can be forgiven for its error. However, the fact is that Moses Fleetwood Walker had enrolled at Michigan in 1881 and had become the first Black player on the university’s baseball team in 1882.26 Ash held the distinction of being Michigan’s first Black baseball player in the twentieth century. As such, he was a precursor to Jackie Robinson. In 1946 Robinson – at the outset of his Hall of Fame career – became the first Black player in the International League since Walker in 1889 (Syracuse) and, in 1947, the first Black player in the White major leagues since Walker in 1884 (Toledo).

Ash made the most out of his on-field opportunities for Michigan. On May 5, against Notre Dame – his former employer – Ash “clouted a home run in the tenth after the score stood 10 all in the ninth and won the game.”27 Two days later, in a victory over Iowa, “Ash’s rap sent in two runs in the early part of the game … [and] in the tenth he again aided in pushing his teammate to third from where he scored on the next play.”28

Ash continued to excel as Michigan went 10-0 in Big Ten Conference play in 1923. In a 6-3 win over the University of Illinois on May 12 in Urbana, Illinois, Ash and catcher Jack Blott were “responsible for the Michigan victory” in front of “[a] crowd estimated at 10,000.”29 Ash was 3-for-5 at the plate and scored a run. Against Ohio State on May 28, he hit an RBI triple in the top of the first inning and scored on an error as Michigan prevailed, 5-2. He went 2-for-4, scored two runs, and stole second base in the seventh inning (which led to his second run scored).30

Ash batted .405 for the season for Michigan’s Big Ten championship squad and made a name for himself in baseball circles.31 He spent the summer back home in South Bend, and, in July he agreed to be co-director of a YMCA camp “for the colored boys of the city” that was “the first camp of its kind to be directed in the state of Indiana.”32 Ash was hailed by his hometown press as the “foremost athlete in the city and Michigan university outfielder extraordinary [sic].”33

Ash had certainly turned heads on the baseball diamond for Michigan in 1923. However, he had failed to distinguish himself in the classroom. In a report about how Michigan’s athletes had fared on their June exams, the Grand Rapids Press noted, “Very few athletes met with reverses during the past term although Rudolph Ash, star Negro outfielder and leading hitter on the Michigan baseball team, failed in his studies and it is doubtful if he will return next season.”34

The Press’s prediction was accurate, and Ash’s collegiate baseball career was at an end. More than a year later, in December 1924, it was reported that “Rudolph Ash, who is attending the University of Chicago, is spending his vacation with his mother, Mrs. Cora B. Hill, 428 South Main Street.”35 Six years after her divorce, Cora had married Henry Hill on July 24, 1923.

The cause for Ash’s failure at the University of Michigan is unknown. The stereotype about college students who like to drink and have a good time, rather than to study and earn a degree, is an old one but is right on the mark for some individuals. Rube Foster implied as much about college students’ drinking and behavior in his 1918 comment after he fired Tom Williams. Whether Ash exhibited some of his father’s fondness for alcohol while in college is a matter of speculation, and unsubstantiated conclusions on the matter would wrongfully impugn an otherwise respectable reputation. One thing is certain, however, and that is the fact that Ash never graduated from the University of Chicago either; the 1940 census lists his highest grade completed in school as “College, 3rd year.”

In 1926, sans college diploma, Ash moved to New York City, though he apparently spent some amount of time in Philadelphia as well. Ed Bolden signed him for his Hilldale (Darby, Pennsylvania) Daisies, a member club of the Eastern Colored League, and gave him only the briefest tryout: one game in which he did not even make a plate appearance. Ash then signed with the ECL’s Newark Stars and was in the lineup for both games of a June 20 doubleheader against the New York Lincoln Giants at the Catholic Protectory Oval in the Bronx. Ash manned right field in both contests and was 1-for-4 at the plate in each game as well. He scored one run in Newark’s 7-6 loss in the opener but did not score in the Stars’ 9-2 victory in the nightcap. The Game Two triumph was the first win in nine ECL games for Newark.36

Ash batted .200 (2-for-10) in three games for Newark, but his stint with the team was not cut short due to his performance. On July 10, the New York Age reported, “The Newark Stars, organized at the beginning of this season by Andy Harris, have ‘given up the ghost,’ at least for the remainder of this season. … Lack of money to pay salaries is said to have caused several members of the team to quit even before the project was finally abandoned.”37

After the Newark franchise folded in 1926, Ash turned his attention to Anna Perdita Sanford, his bride-to-be. The couple was married on June 9, 1927, in Brooklyn. Perdita gave birth to their only child, Rudolph Thaddeus Ash Jr., on November 17, 1928. Ash found steady work to support his new family, but he continued to indulge his love for baseball by playing for various semipro squads for a time, including occasional stints with Ed Bolden’s Darby Phantoms.38 However, baseball was now an avocation and, by the time of the 1940 census, Ash’s occupation was listed as “red cap,”39 and on his 1942 World War II draft registration card he listed the Pennsylvania Railroad as his employer. Ash worked for the railroad until his retirement.

Ash’s father, Thaddeus, had died in May 1928, six months before Rudolph Jr.’s birth, and his mother, Cora, died in 1931. His grandfather, William Henderson, long outlived his wife – Nancy Powell Henderson, who had died in 1922 – and was, in 1940, the last family member from Ash’s childhood home to pass away. Rudolph Thaddeus Ash Sr. died on February 16, 1977, in New York City “after a two-week illness” of an unspecified nature.40 Upon Ash’s death, his body was returned to South Bend for burial.

Rudolph Jr. served in the Army during the Korean War and later worked for the General Motors Corporation. He died on September 26, 1980, in the Veterans Administration Hospital in New Rochelle, New York, at the youthful age of 51.41As had been the case with his father, no cause of death was given, and his body was interred in South Bend.

After the deaths of her husband and son, Perdita Ash – who was originally from Macon, Georgia – moved from New York City to South Bend. Members of her husband’s extended family, the Powells from his maternal grandmother’s side, still lived there and she connected with them. Perdita died on February 17, 1985, at the Fountainview Place nursing home in Mishawaka, Indiana, which is a few miles west of South Bend.42

Rudolph Sr., Perdita, and Rudolph Jr. are buried in South Bend’s Highland Cemetery. They were the last of the Ash family in South Bend, but other descendants of Pharoah and Rebecca Powell still live in the city.

Sources

All Negro League player statistics and team records were taken from Seamheads.com, except where otherwise indicated.

Ancestry.com was consulted for US Census information; military records; as well as birth, marriage, and death records.

Notes

1 Neil Lanctot, Fair Dealing & Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1919-1932 (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1994), 146.

2 “Johnny Gee Starts Fast/Long Michigan Pitcher Does Well for Toronto in Opener; Saginaw Honors Top Bowler, Grand Rapids Press, May 20, 1942: 19.

3 “Michigan Baseball Coaching History,” https://mgoblue.com/news/2009/6/5/michigan_baseball_coaching_history.aspx, accessed June 6, 2021.

4 “Rube Fires Tom Williams Outright: Latter Is Accused of Being Under Influence of Liquor on Training Trip,” Chicago Defender, April 6, 1918: 9. Williams had attended Morris Brown College in Atlanta.

5 Jeanne Derbeck, “Plan Powell House Benefit,” South Bend Tribune, February 24, 1975: 17.

6 “Article 13 – Negroes and Mulattoes,” Indiana Constitution of 1851 as originally written, https://www.in.gov/history/about-indiana-history-and-trivia/explore-indiana-history-by-topic/indiana-documents-leading-to-statehood/constitution-of-1851-as-originally-written/article-13-negroes-and-mulattoes/, accessed June 6, 2021.

7 Travis Childs, “Blacks Settled in the Area Around Potato Creek State Park in 1830s, 1840s,” South Bend Tribune, January 29, 2006: B7.

8 Childs.

9 “‘Handy Boy’ in Civil War Dies at South Bend,” Indianapolis Recorder, February 3, 1940: 8.

10 “South Bend, Ind., Dec. 5, 1906,” South Bend Tribune, December 15, 1906: 30.

11 “Promises to Be Good,” South Bend Tribune, July 11, 1907: 5.

12 “Wife Asks Divorce,” South Bend Tribune, February 23, 1917: 9.

13 “Bold Thief Still Defies Detectives,” South Bend Tribune, October 10, 1911: 5.

14 “In Colored Circles,” South Bend News-Times, June 6, 1918: 6.

15 “World War I Transformed Campus, Opened Indiana University to the World,” IU and World War I, https://news.iu.edu/stories/features/world-war-i-anniversary/iu-during-wartime.html, accessed June 7, 2021.

16 “World War I Transformed Campus.”

17 “World War I Transformed Campus.”

18 “World War I Transformed Campus.”

19 “World War I Transformed Campus.”

20 Ellis S. Bell, “South Bend Ind.,” Chicago Whip, October 4, 1919: 9.

21 “Fosters Upset St. Louis Giants,” Chicago Tribune, July 12, 1920: 15; “Foster’s Giants Win Again, 4-2,” Chicago Tribune, July 13, 1920: 13; “Fosters, 7; St. Louis, 6,” Chicago Tribune, July 14, 1920: 15.

22 “American Giants Trim Dayton Nine Again, 3-1,” Chicago Tribune, July 20, 1920: 14.

23 “Society,” South Bend Tribune, October 9, 1920: 5.

24 “Elster and Reuben Will Clash Again on Ramona Field,” Grand Rapids Press, May 25, 1921: 18. Ash normally played the outfield, both in college and as a professional; however, he did play one game at second base for the American Giants in 1920, so he could play certain infield positions as well.

25 “Rudolph Ash Makes Good at Michigan ‘U,’” Chicago Defender, May 12, 1923: 10.

26 “Moses Fleetwood Walker,” Go Blue: Competition, Controversy, and Community in Michigan Athletics, http://michiganintheworld.history.lsa.umich.edu/michiganathletics/exhibits/show/key-players/fleetwood-walker, accessed June 7, 2021.

27 “Rudolph Ash Makes Good at Michigan ‘U.’”

28 “Rudolph Ash Makes Good at Michigan ‘U.’”

29 “Michigan in Great Rally Beat Illini,” Rockford (Illinois) Republic, May 14, 1923: 8.

30 “Ohio State Fails to Grasp Chance/Michigan Keeps Its Conference Slate Clean by Defeating Our Boys, 5-2,” Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, May 29, 1923: 14.

31 James Tobin, “The Belford Lawson Mystery: A Family Story and Racism’s Long Shadow, Ann Arbor Observer, https://annarborobserver.com/articles/the_belford_lawson_mystery.html#.YL5NPvlKjIU, accessed June 7, 2021.

32 “Will Open Camp Lincoln,” South Bend Tribune, July 22, 1923: 17.

33 “Will Open Camp Lincoln.”

34 “Michigan Grid Heroes Pass June Exams,” Grand Rapids Press, June 28, 1923: 23.

35 “In Colored Circles,” South Bend Tribune, December 22, 1924: 10.

36 “Newark Stars at Last Win Game in Eastern Colored League Race,” New York Age, June 26, 1926: 6.

37 “Newark Stars Disbanded,” New York Age, July 10, 1926: 6.

38 “Corley Cashes In,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 1, 1929: 23; “Phantoms Win First from Rival Foes,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 10, 1929: 18; “Darby Phantoms Win,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 3, 1930: 42. The January 31, 1986, edition of the South Bend Tribune contained a photo of a jersey worn by Ash that had the name Tigers across the front (“Museum Exhibit to Mark Black Experience in Area,” South Bend Tribune, January 31, 1986: 15). Inquiries to the History Museum in South Bend, where the exhibit containing the jersey was housed, yielded no information due to the change of museum personnel in the interval between 1986 and 2021. In a July 13, 2021, email to this author, Negro League researcher Gary Ashwill wrote, “To my knowledge Ash didn’t play for the Philadelphia Tigers, but there were semipro teams in the Philadelphia area in the late 1920s called Tigers – most notably the Main Line Tigers, but also the Norwood Tigers.” No newspaper articles were found to indicate which Tigers team Ash played for, and efforts to locate any surviving members of Ash’s extended family proved unfruitful. Currently, it appears that the year 1930 may have marked Ash’s last attempt to play baseball (whether as a semipro or professional) as the final mention of his name is found in that year’s August 3 edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer.

39 Red caps – so-called because they wore red caps in the early twentieth century – were porters at train stations.

40 “Rudolph T. Ash,” South Bend Tribune, February 20, 1977: 49.

41 “Rudolph T. Ashe,” South Bend Tribune, September 27, 1980: 6. Either Rudolph Jr. added an “e” to his last name, perhaps to distinguish himself from his father, or the Tribune inadvertently added the letter to the name.

42 “Anna Perdita Ash,” South Bend Tribune, February 18, 1985: 20.

Full Name

Rudolph Thaddeus Ash

Born

November 2, 1899 at South Bend, IN (USA)

Died

February 16, 1977 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.