Schorling Park (Chicago)

This article was written by Ken Carrano

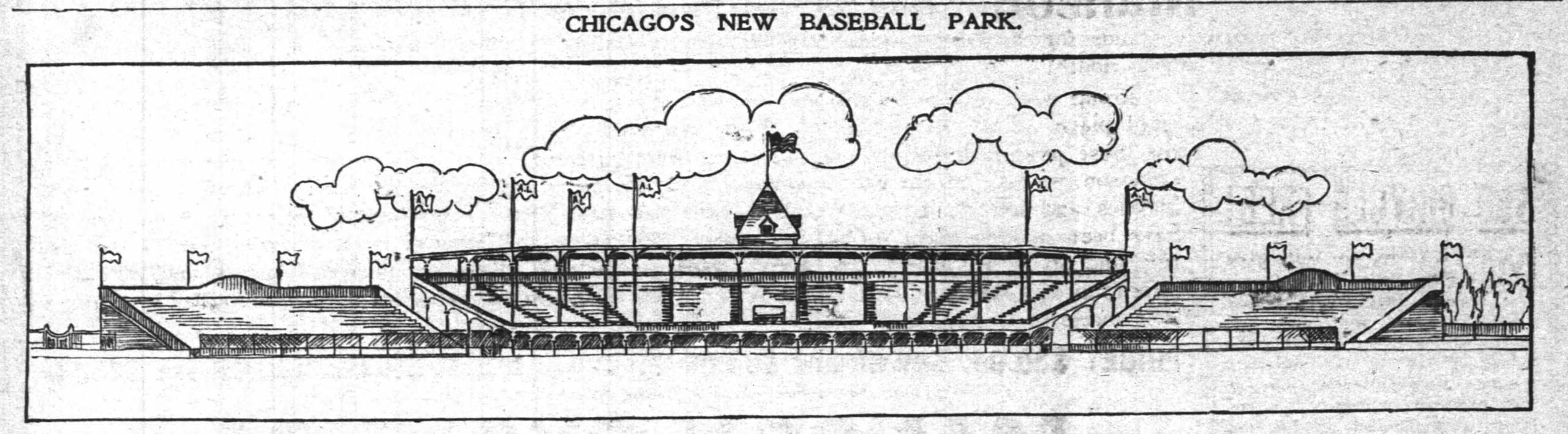

South Side Park, later known as Schorling Park, located on 39th Street between Princeton and Wentworth Streets, hosted its first game on April 21, 1900. (THE INTER-OCEAN, APRIL 8, 1900)

The ballpark on 39th Street in Chicago between Princeton and Wentworth Streets had as many names as any ballpark in the era before corporate sponsorship, when Parks can become Fields (Miller to American Family in Milwaukee) and poorly named Fields can become even more poorly named Fields (US Cellular to Guaranteed Rate in Chicago, a mere half-mile from the present subject). The ballpark in question here spent most of its life known as Schorling (or sometimes Schorling’s) Park, but also spent its formative years as South Side Park, and was alternately known as White Sox Park, the 39th Street Grounds, Cole’s Park, American Giants Park, Cole’s American Giants Park, and an unnamed dog-racing track. Before its life ended in flames in 1940, the ballpark hosted numerous Hall of Famers, two of the most important baseball moguls in the sport’s history, presidential candidates, community events, and possibly every other organized sport played on the South Side of Chicago. Its legacy exists in the assistance given to the formation of two major leagues. Schorling Park’s life was a three-act play – the first almost entirely White, the second primarily Black with White accents, and the third a mixture of man, machine, and animals. The ballpark’s story officially begins in 1900, but before that, attention must be turned to a cricket pitch.

Prologue

The Wanderers Cricket Club was formed in April 1883 and started its life by playing at Lincoln Park, along the shore of Lake Michigan north of Chicago’s downtown.1 By April 1884, however, because Lincoln Park, a public facility, was not always available, the cricket club had moved to a new ground on the South Side of Chicago at 37th Street and Indiana Avenue. By 1886, the Wanderers had branched into other sports, with reports in the local papers noting their games of rugby and soccer. In addition, a tennis club that had leased part of its grounds was absorbed by the Wanderers.2 In 1887 baseball joined the party when some druggists and doctors who had been using the club grounds joined the club and formed the Wanderers Baseball Club.3 The club, then hosting 145 male and 24 female members, planned to build a toboggan slide and flood the field for ice skating.

Gambling was in vogue at the Wanderers grounds. In September 1887, nearly 2,000 cranks paid 25 cents apiece to see a 100-yard race between two local athletes. When only one of them showed up for the race and ran, the stakeholders refused to pay the “winner,” and management refused to refund the admission fee.4 In 1890 the Wanderers expanded their mission to include track-and-field athletes, hosting these Olympic-type events at the 37th Street Grounds. After merging with another club in 1893, the Wanderers wandered a few blocks to the intersection of 39th Street and Wentworth Avenue, where its members had easier access to the streetcar line on Wentworth that traveled downtown. In early 1894, the Wanderers sponsored a concert to raise funds for new tennis courts and improvement of the facilities.5 The larger physical plant at 39th and Wentworth allowed the Wanderers to host multiple events – on November 29, 1894, the grounds hosted an American football game at 9:30 A.M., a soccer match at 11 A.M., and a cricket match at 2:30 P.M.6 In late 1894 the Wanderers built a shed large enough to host five curling rinks.7 The club continued to add to its facilities and by January 1900 had built a hockey rink and was looking for opponents.8 However, before the ice on the rink could melt, the club was on the move and a new tenant was moving in.

Act One – A Mogul Comes Home

No matter where Charles Comiskey was playing or managing in baseball, he always knew that he would eventually come home. His father, Honest John Comiskey, came to Chicago in 1854 and settled into a life of public service, at various times holding the positions of clerk of the County Board of Commissioners, superintendent of the water meter department, and Chicago alderman.9 Charles, born in 1859, had baseball, not public service, running through his veins. After a career as a first baseman and manager, including time with the Chicago entry in the Players’ League (playing just a half-mile from the Wanderers Cricket Grounds at 35th and Wentworth), Comiskey became an owner as he took over the Sioux City, Iowa, franchise of the Western League and relocated it to St. Paul, Minnesota, in time for the 1895 season. Comiskey spent $4,000 to build a 1,500-seat ballpark in the Summit-University section of St. Paul, pulling his father out of retirement to act as construction supervisor.10 But Comiskey and Western League Commissioner Ban Johnson had grander goals, and when the National League contracted four teams after the 1899 season, the men saw a “major” opportunity.

The Western League team owners met in Chicago in October 1899, renamed it the American League, and announced that teams might relocate to Cleveland, Buffalo, and Chicago.11 Shortly, Comiskey said, “The American League will have a team in Chicago next year. It will be located on the South Side, and I will give Chicago a team of which it will be proud.”12

Where exactly on the South Side still needed to be determined. At one point, Johnson asserted that Comiskey was planning to have a large raft anchored off the Lake Front (now Grant) Park to accommodate his patrons.13 Finally, in March 1900, some news came on the name of the team and where it would play. Comiskey expressed his frustrations with finding a location, declaring, “I will either have a team in Chicago or else go on the police force.”14 The Chicago Inter-Ocean stated that Comiskey would name the club the White Stockings, the former name of the Chicago Orphans when Adrian “Cap” Anson ran the team. Comiskey met with the architect who had drawn up preliminary designs on a ballpark that Anson was considering building on the South Side earlier in the year. On March 6 Comiskey said he had secured the leases and would announce the location of the ballpark before the end of the week.15 Two days later, the Wanderers Cricket Club announced that it was taking over the grounds of the former Chicago Cricket Club on 79th Street. It was rumored that their old plant on 39th Street would become the home of the White Stockings, but Johnson denied this.16

In addition to the issues of finding a home, there were issues with the other team in town. Orphans President James Hart was not fond of the idea of sharing the city with an American League team, although he did not express his concerns at first. “Our league was invited into Chicago last fall when Jim Hart told President Johnson to go ahead and make arrangements for a Western League team in Chicago,” Comiskey said. “We then changed the name of the organization from the Western League to the American League, and immediately began our preparation for the coming season. Then, and not until then, did Hart announce that under no circumstances would he consent to our entering Chicago.”17 The situation was resolved in late March when Hart, Johnson, and Comiskey worked out a compromise, and Comiskey finalized plans for the ballpark to be located at 39th and Wentworth.18 Comiskey agreed to build his ballpark south of 35th Street, but it appears that he already had secured the Wanderers’ old grounds.

Now that the ground had been secured, Comiskey had to go about the business of getting the ballpark built in time for the April start of the 1900 season. Honest John had died earlier in the year, so Comiskey decided to become his own general contractor. His first payday found him with cash in the bank but none in his pockets to pay his men, and as this payday was also Election Day in Chicago, the banks were closed. After getting a hotel to cash his $1,500 check into $100s and $50s, Comiskey still needed to break the bills further, sending his groundskeeper to every bar and grocery store in the area to get what he needed to pay the workers.19 Work continued on the grandstands, and Comiskey announced that, in spite of the snowy April, his ballpark would open on Sunday, April 15, 1900, with a game against the Union Giants, “the crack colored team.”20 The weather would not cooperate as the grounds were too wet, and the game with the Unions was canceled. The ballpark’s debut had to be delayed until April 21, the opening game for the new league in Chicago, against the Milwaukee Brewers. Some 5,200 hardy souls attended the opener, which the Brewers won, 5-4, including painters who continued to paint the fence while the game proceeded: “Two painters were just beginning work on the fence, and why they did not twist their necks off every time someone hit the ball it is impossible to say,” the Chicago Tribune commented.21

Like many ballparks of this era, the outfield fences had to conform to the neighborhood surroundings, in this case the greenhouses of the J.F. Kidwell company. South Side Park had a spacious left field (398 feet to straightaway left), but the distance narrowed significantly as the fence moved to right, with the opening dimensions showing the right-field line a short 270 feet away. The park was oriented to the northeast, with the third-base line running parallel to Princeton Avenue and the first-base line running along 39th Street (Pershing Road). The tight location of the park caused Comiskey some issues early on, with the Chicago Tribune reporting on April 25 that “Comiskey’s troubles commenced, for the greenhouse man just over right field fence is threatened with nervous prostration caused by the home runs which occasionally threaten his glass houses, and a factory across the road from the park has a claim for one plate glass window smashed by the unusually strong flight of a foul, which sailed across the grandstand and clear through Thirty-ninth street through the window and into the factory.”22 Although the ballpark was operational, it clearly was not completed. The White Stockings left on April 27 for a road trip that would take them to every other American League city, and Comiskey used the time away to sod the diamond, add new entrances and exits, and paint the grandstand and bleachers.23

The White Stockings captured the inaugural American League pennant in 1900, and with the announcement that the American League now considered itself a major league, the stakes were raised. South Side Park was the host of the first game in the history of the now major AL on Wednesday, April 24, 1901, defeating the Cleveland Blues, 8-2. The Blues’ Jack McCarthy had the honor of securing the first hit in AL history with a single in the first inning. Nine thousand was the listed attendance for the inaugural game, under the estimated capacity of 12,500. Four days later, on Sunday the 28th, 15,000 packed the park to see the White Stockings beat the Blues again, this time in a 13-1 rout. Comiskey took advantage of an 18-day road trip in early June to make further improvements to the grounds, adding box seats to the roof of the grandstand and extending the bleachers, thereby increasing the stated capacity of the park to 14,000.24 Even with this additional capacity, Comiskey found he did not have enough seats for his patrons, with two September Sunday home dates drawing more than 18,000 fans to the South Side: “Comiskey may have had his first inkling that the 39th Street Grounds were wholly inadequate for professional baseball when 30,08425 fans jammed the park on October 2, 1904, to cheer on Doc White as he attempted to extend his scoreless-inning streak past 45 (innings).”26

Even with the right-field wall extended out over time, South Side Park was a pitcher’s paradise. In its 10-year existence as an American League home field, the ballpark on 39th Street hosted four of the first 11 no-hitters thrown in the AL. The first of the four, on September 20, 1902, was thought for years to be the first thrown in the American League, until further research by SABR member Gary Belleville determined that Pete Dowling threw a no-no in June 1901.27 The highlight for White Sox fans during the team’s tenure at South Side Park was the 1906 World Series against the crosstown rival Chicago Cubs. The games were alternated each day, with the Cubs’ West Side Grounds hosting Games One, Three, and Five and South Side Park hosting games Two, Four, and Six. Surprisingly, the White Sox’ Hitless Wonders won all three games played on the West Side, and won only Game Six at their home ground. If the 1904 game that drew over 30,000 fans was not enough to convince Comiskey that his park was undersized, he had to look no further than the prior World Series, in which the New York Giants had attendance of 62,777 for their three home games vs. the 50,229 who attended games on the South Side.

Comiskey signed the death warrant for South Side Park in 1909 when he purchased a tract at 35th Street and Shields.28 The area was familiar to him – this was the location of the Brotherhood Park that Comiskey managed in 1890. It would take many months before the Comiskey Park groundskeeper could rid the field of alfalfa that grew in what would be center field once the ballpark opened.29 Even with the new ballpark coming, Comiskey was committed to his current location, touring South Side Park in February 1909 with an architect to make improvements to the grandstands and pavilions.30 Comiskey also continued his habit of allowing others to use the ballpark. The Comiskey Cup was a lacrosse tournament held at the park for several years. Comiskey also agreed to allow an acetylene lighting system to be used in a running event on May 26, 1909, in which the competitors would circle the outfield at night. Comiskey was hesitant to allow the event during the day, because it would have been competition for the Cubs.31

Before the acetylene light could become a fire hazard, the park dodged a bullet when fire consumed the 50-cent stands in right field, about 40 feet from the main grandstand, on April 25, 1909. There was no clear indication of how the fire started, but it was suspected that a lighted cigar was dropped into the woodwork below the stands during the game with the St. Louis Browns that afternoon. The fire was discovered by a person who lived across the street from the ballpark and called the fire department. Firemen had to break into the grounds and, with the fire chief directing the operations from the middle of the diamond, were able to restrict the damage to the right-field pavilion. Comiskey estimated the damage at $5,000 and speculated that it would reduce the capacity of the park by 4,000. According to the Chicago Tribune, Comiskey was not all that concerned when he received a phone call alerting him to the fire, choosing instead to have a second helping of his wife’s shortcake.32 However, as soon as the fire was put out, workers started removing the still-hot beams and carpenters were secured to start rebuilding the grandstand. Cubs President Charles Murphy had offered the use of the West Side Grounds to Comiskey, but with the damage limited, Comiskey declined the offer and the game scheduled for April 26 against the Browns went on as planned, a 1-0 White Sox victory. “I appreciate the offer of President Murphy to give us the use of the West Side grounds, when he understood we had been burned out, but I am glad we will not be compelled to accept his generosity,” Comiskey said.33

The cornerstone of the Old Roman’s new ballpark was laid on March 17, 1910, and South Side Park hosted its last American League game on June 27, 1910, a 6-2 loss to Cleveland. Even before the final game, Comiskey had found a new tenant for the park: “John Schorling has leased the old White Sox grounds for baseball purposes at 39th and Wentworth,” a local publication wrote. “Johnny will make a success of it as he is an authority on these affairs, and is a popular manager. We hope he will put in a white team.”34 He did not.

Game action at South Side Park, later Schorling Park, in 1907. (CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM)

Act Two – A New Mogul Arises

Frank Leland had a lot to do with the formation of the Chicago American Giants, but probably did not realize that he was doing this. Andrew “Rube” Foster was a pitcher and eventually manager for the very successful Leland Giants and was taking on more and more responsibility for team operations. Leland was a figurehead. “In reality, Leland had nothing to do with the success of the club. Fed up with the humiliation, Leland announced that he would form a new club known as ‘Leland’s Chicago Giants Baseball Club’”35 Foster subsequently sued Leland for using the name, and won a court battle when a judge ruled that “hereafter no person or persons acting for the defendant [Frank Leland] shall in any fashion use the name ‘Leland Giants’ as the name of the defendant club or feature the name ‘Leland’ in connection …”36 This did not stop Leland from using his own name, and Chicago had two Leland Giants teams playing in the city.

Subsequently, “[i]n 1911[,] Foster entered into a partnership with a White businessman named John Schorling. Together they bought the ballpark that Charles Comiskey was vacating as he moved his White Sox into their sparkling new stadium, the current Comiskey Park, on 35th and Shields.”37 The original Leland Giants had played some of their games at Auburn Park, where Schorling, a tavern owner on the south side of the city, also managed a Chicago City League team and owned the ballpark at 79th and Wentworth. He was also a board member of the Leland Giants:

“Schorling had been the landlord for the Leland Giants at Auburn Park since 1905. Dealing directly with Schorling was a signal that he had cut ties with his business partners and would go it alone. The scheme Rube Foster hatched with Schorling was ambitious. He envisioned a repeat of the 1909 season with large crowds in attendance for games with top notch cross-town foes, East Coast teams, Cuban teams and culminating with an epic battle against either the National League Cubs or American League White Sox. Foster saw no reason why his team shouldn’t play before large crowds every day – like Chicago’s other major league teams.”38

While Schorling had arranged his lease for South Side Park, he could not take possession immediately. The Chicago Tribune noted, “Schorling plans to open his new plant next spring, the present park remaining in the possession of the White Sox magnate until next November.”39 Work eventually started on the park in March 1911: “The process of converting the old White Sox grounds at Thirty-ninth Street and Wentworth Avenue into a semi-pro plant was started yesterday, when the first clods of earth were turned by workmen employed by John Schorling, lessee of the new way station on the Chicago Baseball League circuit.40 The new ballpark was estimated to hold 4,500 and cost $15,000. Schorling had to have new stands built because the former owner, Comiskey, had taken out the existing stands: “Comiskey’s excuse was that he did not want another club so close to the White Sox grounds.”41 Foster, for his part, was happy with his ground, averring, “Our park, on the South Side, is the finest semi-pro park in the world, reached by every streetcar in Chicago, right in the city.”42

It did seem to Comiskey that Foster and Schorling were on the right track. There was one potential stumbling block, and “Comiskey, by all accounts, sought to convince [Schorling] and Foster that a new black baseball team in Chicago could not succeed if it scheduled games when the hometown White Sox were in town. Foster ignored Comiskey’s advice, and the American Giants thrived. Ponying up 50 cents for admission entitled patrons to free ice water when they flocked to Schorling Park to watch black baseball’s premier team.”43 Opening Day at Schorling Park for the American Giants was on May 13, 1911. “It was a momentous occasion, as the American Giants now had the keys to a major league park. There were locker rooms for home and visiting teams complete with hot showers.”44 The American Giants lost the inaugural game to the Spaldings (sponsored by Albert Spalding) in threatening weather in front of only 3,000 people.45 The weather improved, and initially Schorling Park hosted many patrons: “One Sunday afternoon in 1911, an overflow crowd of 11,000 congregated to watch the American Giants; at nearby Comiskey Park, 9,000 had shown up to see the White Sox; across town, only 6,000 were attending a Cubs’ game.”46 However, the crowds did not last as long as Foster had hoped. When the Chicago City League’s best player, Jim Callahan. left his squad to join the White Sox, attendance at most City League games plummeted. The American Giants also were affected in that “[t]he loss of Callahan was a crushing blow to the City League as both the quantity and quality of play dropped off. Foster never intended to depend on the City League for his livelihood. He was more interested in competition on a national level, however finding worthy opponents and drawing crowds was tougher than expected.”47

Schorling also knew that an idle ballpark would not ring the cash register. He was actively seeking partners in the ballpark’s operation. A classified advertisement in the Chicago Tribune noted that concessions were for sale at “the best semi-pro ball park in the city.”48 In October 1911 Schorling Park hosted a professional wrestling match that featured Illa Vincent, “The Black Panther,” who defeated Frank Ehrler, “The German Thunderbolt.” It was noted that great credit was to be given to the promoters, as the match was “on the square.”49 Schorling Park hosted a great number of different events throughout its lifetime as a sporting venue. From 1914 through 1917, the Chicago Cornell-Hamburgs played many of their games at Schorling, drawing as many as 2,500 to watch the nascent pro football team.50 The American Giants were not the only baseball team fighting for glory at Schorling Park. Numerous high-school and amateur games were played there. In 1913 Schorling donated the use of the park as a fundraiser for the South Side Old Folks Home.51

As the Federal League emerged, rumors circulated that the league had secured an option on Schorling Park for the Chicago entry to use. Schorling put these rumors to bed, stating, “No one holds an option on the American Giants Park at present. There was talk some time ago, but nothing came of it. Manager Rube Foster signed players for his 1914 American Giants club, and we expect to have a colored team of the same caliber as he has played there in the past.”52 The Federal League’s Chicago Whales eventually chose a location on the North Side of Chicago that most people now know as Wrigley Field, though its original name was Weeghman Park. In May 1914 Schorling told the Chicago Broad Ax what it took to have a successful ballpark, stating, “Was first to have a good team, secondly to have the arrangement of your seating capacity so as to give your patrons a good view, and third a good diamond. It takes a good deal of expense to keep a park in order and I want to say this that nowhere in the United States today, can you get the same amount of service as you get at the American Giants base ball park.”53

That 1913 American Giants team had claimed the Western championship but lost four of five games to the New York Lincoln Giants in August of that year. The American Giants continued their winning ways during that decade, claiming championships in 1914, 1916, 1917, and 1918. The no-hitters that were prevalent when the White Sox occupied the 39th Street grounds did not disappear when the American Giants called the ballpark home. Frank Wickware faced the minimum 27 batters in his 1-0 no-hitter against the Indianapolis ABC’s on August 26, 1914. Wickware walked George Shively to start the game. After Shively was thrown out stealing, Wickware retired the next 26 hitters to complete his gem. Dick Whitworth threw a 4-0 no-hitter against the American Giants on September 19, 1915, and the Giants’ Tom Johnson threw a 7-3 no-hitter against the Detroit Stars on June 17, 1919. Six walks and three errors by Bobby Williams contributed to the odd scoreline.54 Perhaps the best pitching matchup of the decade, at least for star power, occurred on June 8, 1914, when Rube Foster met Cy Young, pitching for Benton Harbor, at Schorling Park, with Foster prevailing, 5-4.55

Because of the Spanish flu56 pandemic, the World Series was completed by early September in 1918, leaving the American Giants as the only game in town. They played four games over three weekends against a collection billed as the Major League All-Stars, including Hippo Vaughn and Red Faber. Foster’s squad won three of the four contests.57 Eventually, the Chicago health department shut down public gatherings, eliminating what would have been a lucrative exhibition between the American Giants and a barnstorming team led by Vaughn.58

The 1919 season was interrupted at Schorling Park as well, but not due to the pandemic. Schorling Park was located on the edge of the White working-class Bridgeport neighborhood. A block away sat the neighborhood now known as Bronzeville, an area settled by many African Americans who moved from the South during the Great Migration. Racial tensions boiled over that summer, and the American Giants were affected as well:

“On July 27, 1919, a black youth swimming at near a “white” beach was attacked by a stone-throwing white male. The youth drowned, and when the police took no action against the white perpetrator, a riot broke out. After five days, the rioting and looting had claimed the lives of 23 blacks and 15 whites. The National Guard was called out and bivouacked at Schorling Park as order was restored. The American Giants canceled a number of games, playing many in Detroit. The American Giants did play a few games back at Schorling Park in September, but Foster used his time on the road to solidify the relationships that would help form the Negro National League (NNL) the next year.”59

The NNL brought a level of organization to Black baseball that had been years in the making. However, the new league did come with increased operating expenses, and Schorling needed to increase gate receipts. The April 10, 1920, edition of the Chicago Defender announced that prices would rise for the 1920 season – bleacher seats would cost 30 cents, grandstand seats were now 50 cents, and box seats commanded 75 cents, all inclusive of the still-in-place war tax. It was noted that these prices were still much below the prices charged to see White big-league ball.60 Foster’s men did the former occupants of the ballpark one better by winning the NNL crown in 1920, 1921, and 1922. The success of the team brought big crowds to 39th and Wentworth, which sometimes caused trouble. The May 7, 1922, game between the American Giants and Kansas City Monarchs was ended after the eighth inning because of unruly fan behavior. An overflow crowd of 16,000 to 17,000 had begun to swarm the field. Efforts by Foster and other players to ask the fans to move back were futile. When the American Giants tied the game in the eighth, fans rushed the field. Seat cushions were thrown around, and soon soda bottles were thrown as well. Patrons had brought whiskey into the park and sold it in the rest rooms. (Prohibition had started in 1920.) The actions of some women in the ladies’ restroom were deemed not fit to put into print. Schorling later asked federal agents to come to games to prevent future riots.61

Another incident occurred between the American Giants and Monarchs in 1923, but this time faulty construction was to blame. The popularity of the American Giants had caused Schorling to install temporary bleachers. A section of the bleachers collapsed in the seventh inning of a game on May 27, 1923, causing 1,500 patrons to tumble to the ground. Remarkably, only 28 people required trips to hospitals. Several hundred more were bruised but remained at the game. Once the injured were attended to, the game resumed, with the American Giants prevailing, 5-4.62 Later that year, Schorling Park hosted many of the 30,000 Elks who paraded through the South Side, ending at the ballpark, where numerous events, including a ballgame and performances by drill squads, were held.63

The American Giants, like the White Sox before them, won the first several league pennants without the added benefit of participating in a World Series – because one did not exist. However, the Negro World Series came to Chicago without the American Giants in 1924 when Games Eight through Ten of the Negro League series between Hilldale and the Monarchs were played in Schorling Park. For an understanding of scale, the 1924 major-league World Series generated $1,098,104, while the Negro League Series generated $52,000. The winning share for the victorious Monarchs was $308 per player, while the Hilldale athletes received $193 each.64 Schorling Park also hosted playoff games for the NNL pennant in 1925. In 1926 the American Giants won the second-half title in a tight race with the Monarchs, defeated the Monarchs in a playoff series to win the pennant, and triumphed over the Eastern Colored League’s Atlantic City Bacharachs to win their first Negro World Series. The final five games of the series were played at Schorling Park, with the American Giants prevailing in the 11th and final game of the Series, 1-0, behind Rube Foster’s brother Willie, who gave up 10 hits but escaped multiple jams before the American Giants plated the winning run in the bottom of the ninth inning. Fans carried their heroes off the field and celebrated on nearby State Street.65

Act Three – Gone to the Dogs

Tempering this celebration was the loss of Rube Foster. Earlier that year Foster had suffered what appeared to be a nervous breakdown, and had been committed to an asylum in Kankakee, Illinois. There was apparently no written contract between Schorling and Foster, and Schorling essentially took over the club, offering no compensation to the Foster family.66 Sarah Foster, Rube’s wife, offered some hope of Rube’s comeback when she and Schorling attended a joint NNL/ECL meeting in January 1927, but league leaders were preparing to move on without Foster.67 Schorling appointed Dave Malarcher as manager, but quietly sold the team to William Trimble, a White racetrack owner. The American Giants repeated as World Series champions, again defeating the Bacharachs, this time five games to four, with the first four games played at Schorling Park.68

The 1928 NNL season was not as successful as the previous two had been, with the American Giants losing the NNL playoff to the St. Louis Stars and then slipping to third place in 1929. Trimble seemed to take less of an interest in the team, preferring to stay in Florida rather than get the team ready for the season.69 The American Giants’ slide continued in 1930, but that year brought an innovation to Schorling Park – night baseball. The Monarchs brought their portable light system to Chicago for night games on June 21 and 22.70 Seeing how popular the night games had been, Trimble put up lights at the ballpark less than six weeks later.71 Another nine years passed before the Chicago White Sox installed lights, playing their first night game on August 14, 1939. Wrigley Field did not install lights until 1988.

In 1931 Monarchs owner John Wilkinson discussed his idea to move the Monarchs to Chicago. The ballpark had deteriorated, especially after Schorling sold the team. Wilkinson believed that the cost to renovate the facility would be several thousand dollars,72 but he was still considering the move because “Chicago is the best baseball town in the country and I am sure a good team, proper accommodations and such would revive the sport to the level it once enjoyed.”73 In the end, Wilkinson decided that the cost would be too great to overcome and kept the Monarchs in Kansas City.74 In addition to the possibility of the Monarchs moving to Chicago, there was interest in starting a professional Negro football league, with the presumed Chicago team playing at Schorling Park.75 While the Monarchs’ move was squashed, two other promoters, Abe Saperstein and Robert Cole, were interested in purchasing the team. Saperstein’s idea was to take the American Giants on the road as a traveling attraction, and he hoped to team Willie Foster with Satchel Paige. The team he put together, called the Rube Foster Memorial Giants, fell apart quickly, but Cole was able to put together a package to take control of the ballpark and reestablished the team. Cole immediately began improving what would now be known as Cole’s American Giants Park, adding new bleachers and field boxes, and installing a loudspeaker system.76

Just as Cole and his team were making positive strides, it had to move. Cole had only a one-year lease on the ballpark, and it was not renewed. The ballpark was said to have been in “the hands of receivers for years,” and it was leased to become a dog racing track.77 Cole had the team play some games at Mills Park in Chicago, but the majority of his squad’s “home” games took place in Indianapolis. The dog park never opened. Illinois Governor Henry Horner approved of dog racing, but only if there was no pari-mutuel betting. As a result, Cole was able to take over the ballpark again in 1934, after having the venue converted back into a baseball facility. The 1934 American Giants returned to respectability, and Cole’s American Giants hosted several games of the playoff series with the Philadelphia Stars, which the Giants eventually lost.

Cole became less interested in running the team and sold the franchise to his assistant, Horace Hall, in the summer of 1935. As baseball moved slowly toward integration, more and more Black fans attended games at the various major-league ballparks that had been integrated. In fact, “[i]t was ‘hip’ among some Chicago blacks to check out the White Sox.”78 Attendance at American Giants Park suffered because of this, and no funds were available to keep the old wooden ballpark in shape. More and more nonbaseball attractions were brought in to keep the cash registers ringing. In July 1938 Olympic champion Jesse Owens appeared in exhibitions during a series between the American Giants and Birmingham Black Barons.79 Boxing champion Joe Louis appeared in a horse show at the ballpark in September.80 Louis also appeared in an all-star softball game a few days later. Chicago public high-school football games were held on those weekends when the American Giants were on the road. In September 1939, a midget-racing program for Black drivers was held on the field.81 On September 13, 1940, presidential candidate Wendell Willkie campaigned on the south side of Chicago, holding a rally at American Giants Park that drew 15,000.

But the end was near. Vandals set fire to the ballpark on December 23, 1940, and the dilapidated structure burned quickly. The fire started in the third-base stands, and damage was estimated at between $2,000 and $8,000. Hall declared that the stands would be rebuilt immediately, but the second major fire at the ballpark was also its last.82 “It was a historic landmark in the history of Negro League baseball. Yet, no one shed tears when (Schorling Park83) burned, as there was universal agreement that the old wooden ballpark had outlived its usefulness.”84

Epilogue

The American Giants still had a team, but now had no ballpark for the 1941 season. Neither Hall nor the Negro American League seemed concerned about this problem, causing Fay Young of the Chicago Defender to write, “People cannot understand why, in a city like Chicago, that we have a ballpark which wouldn’t be a credit to the Negros of Chittlin Switch, Mississippi. The money is here. The question is who will invest”85 A group of investors did consider rebuilding the park, only to be scared off when they heard the American Giants owed $2,800 in back taxes on ticket sales.86 Eventually what was left of the ballpark was razed. In 1945 Wentworth Gardens was built on the site to house war-industry workers. It is now a public housing project owned by the Chicago Housing Authority.87 A marker stands at the northeast corner of 39th Street (Pershing Road) and Wentworth Avenue commemorating the life of Andrew “Rube” Foster, but there is no tribute to the ballpark that once stood on that site, where baseball immortals like Comiskey, Rube and Willie Foster, Young, Ed Walsh, Walter Johnson, Ty Cobb, John Henry Lloyd, Oscar Charleston, Paige, and Josh Gibson once played for their fans.

Sources

Books

Axelson, G.W. Commy – The Life Story of Charles A. Comiskey (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003)

Benson, Michael. Ballparks of North America (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1989)

Cottrell, Robert Charles. The Best Pitcher in Baseball (New York: New York University Press, 2004)

DeBono, Paul. The Chicago American Giants (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2007)

Holway, John. The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues (New York: Hastings House, 1990)

Lindberg, Richard C. Stealing First in a Two-Team Town (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1994)

Lowry, Philip J. Green Cathedrals (New York: Walker & Company, 2006)

Newspapers

Chicago Defender via ProQuest through the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

Chicago Broad Ax and Chicago Daily News through www.genealogybank.com

Chicago Inter-Ocean, Chicago Tribune, and Southtown Economist through www.newspapers.com

Online

www.kalracing.com

www.thecha.org

Notes

1 “The City,” Chicago Tribune, April 29, 1888: 20.

2 “The Wanderers Club,” Chicago Tribune, October 2, 1887: 26.

3 “The Wanderers Club.”

4 “Only One of Them Sprinted,” Chicago Tribune, September 2, 1887: 9.

5 “Notes of Sport,” Chicago Tribune, January 7, 1894: 7.

6 “Football Carnival Today,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, November 29, 1884: 4.

7 “Curlers Get Busy,” Chicago Tribune, December 12, 1894: 11.

8 “Wanderers Build a Hockey Rink,” Chicago Tribune, January 2, 1900.

9 Richard C. Lindberg, Stealing First in a Two-Team Town (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1994), 13.

10 Lindberg, 35.

11 Lindberg, 40.

12 “Two Clubs in Chicago,” Chicago Tribune, November 21, 1899: 4.

13 Untitled, Chicago Tribune, January 13, 1900: 6.

14 “Comiskey Issues an Ultimatum,” Chicago Tribune, March 3, 1900: 6.

15 “He Names the Club,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, March 7, 1900: 8.

16 “Wanderers Move to Parkside,” Chicago Tribune, March 9, 1900: 9.

17 “Chicago’s New Club,” Chicago Tribune, February 25, 1900: 10.

18 “Left to the Lawyers,” Chicago Tribune, March 20, 1900: 9.

19 Lindberg, 5-7; “Comiskey’s Trials as Contractor,” Chicago Tribune, April 4, 1900: 6.

20 “New Stands Are Ready,” Chicago Tribune, April 12, 1900: 4.

21 “Brewers Win Opening Game,” Chicago Tribune, April 22, 1900: 17.

22 “Target for Home Runs,” Chicago Tribune, April 25, 1900: 6.

23 “Comiskey Signs Waler Brodie,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, April 27, 1900: 8.

24 “Improves South Side Park,” Chicago Tribune, June 27, 1901: 6.

25 The attendance total per Baseball-Reference.com was 30,098. https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHA/CHA190410021.shtml

26 Lindberg, 81.

27 No-hitters at South Side Park: September 20, 1902, Jim Callahan, Chicago White Sox; August 17, 1904, Jesse Tannehill, Boston Americans; September 20, 1908, Frank Smith, Chicago White Sox; April 20, 1910, Addie Joss, Cleveland Naps.

28 “New Ball Park for $100,000,” Chicago Tribune, January 20, 1909: 13.

29 Lindberg, 83.

30 “Plans Improvements at White Sox Park,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, February 23, 1909: 9.

31 “Marathon Stars in Local Event,” Chicago Tribune, April 14, 1909: 10.

32 “White Sox Park Scorched,” Chicago Tribune, April 26, 1909: 1.

33 “White Sox Park Is Menaced by Fire,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, April 26, 1909: 1-2.

34 Untitled, Southtown Economist, June 24, 1910: 4.

35 Paul DeBono, The Chicago American Giants (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2007), 32.

36 DeBono, 33.

37 Jerry Malloy, “Rube Foster and Black Baseball in Chicago,” Baseball in Chicago – 1986 SABR Convention Journal.

38 DeBono, 36. Also Harold McGrath, “In the Field of Sport,” Indianapolis Freeman, January 28, 1911.

39 “Semi-Pro Magnate Leases Sox Park for Next Season,” Chicago Tribune, June 16, 1910: 10.

40 “Start Work on Old Sox Park,” Chicago Tribune, March 11, 1911: 21.

41 “Fire Destroys American Giants Ball Park Seats,” Chicago Defender, January 4, 1941: 24.

42 Andrew “Rube” Foster, “Negro Baseball,” Indianapolis Freeman, December 23, 1911: 16.

43 Robert Charles Cottrell, The Best Pitcher in Baseball (New York: New York University Press, 2004), 63.

44 DeBono, 37.

45 DeBono, 37.

46 Cottrell, 63.

47 DeBono, 37.

48 Classified ad in Chicago Tribune, May 6, 1911: 15.

49 “Illa Vincent, The Black Panther, routed Frank Ehrler, The German Thunderbolt,” Chicago Broad Ax, October 14, 1911: 2.

50 Pro Football Archives: https://www.profootballarchives.com/1916chich.html.

51 “Benefit for the Old Folks Home,” Chicago Defender, August 16, 1913: 8.

52 “American Giants Hold Park,” Chicago Tribune, December 31, 1913: 12.

53 “Banquet and Reception to Rube Foster and His American Giants at Odd Fellows Ball,” Chicago Broad Ax, May 2, 1914: 2.

54 Nonohitters.com: https://www.nonohitters.com/negro-leagues-no-hitters/.

55 “American Giants Victors, 5-4,” Chicago Tribune, June 8, 1914: 11.

56 It was called the Spanish flu but not because it was known to have originated in Spain. It was actually identified in America, Europe, and Asia at about the same time.

57 “All-Star Leaguers Will Compete Against American Giants,” Chicago Defender, September 28, 1918: 9.

58 “Influenza Epidemic Closes Season for American Giants,” Chicago Defender, November 2, 1918: 9.

59 DeBono, 71-72.

60 “Prices Up,” Chicago Defender, April 10, 1920: 11.

61 “Near-Riot Stops Baseball Game,” Chicago Defender, May 13, 1922: 1.

62 “1,500 Periled, 28 Hurt When Ball Stand Collapses,” Chicago Tribune, May 28, 1923: 3.

63 “30.000 Colored Elks Hep-Hep to 25 Jazz Bands,” Chicago Tribune, August 29, 1923: 9.

64 John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues (New York: Hastings House, 1990), 195.

65 DeBono, 114.

66 Cottrell, 171.

67 DeBono, 115.

68 The White newspapers generally called the park American Giants Park or South Side Park after Schorling sold the team to Trimble.

69 DeBono, 122.

70 “Night Baseball,” Chicago Daily Times, June 21, 1930: 24.

71 DeBono, 125.

72 “K.C. Boss Dickers for Chicago Park,” Chicago Defender, August 8, 1931: 9.

73 “K.C. Boss Dickers for Chicago Park.”

74 DeBono, 131.

75 “Professional Football to Hit Chicago,” Chicago Defender, September 26, 1931: 8.

76 DeBono, 133; “Old Park Dresses Up,” Chicago Defender, March 6, 1932: 22.

77 “Giants Lose Ball Grounds: Old Schorling Park Will Be Home of Dogs,” Chicago Defender, May 6, 1933: 8.

78 DeBono, 145.

79 “Jesse Owens in Two Track Exhibitions,” Chicago Daily News, July 1, 1938: 17.

80 Advertisement in the Chicago Metropolitan Post, September 10, 1938: 14.

81 http://www.kalracing.com/autoracing/Chicago_American_Giants_Main_Page.htm.

82 “Fire Destroys American Giants Baseball Seats.”

83 The Black press, specifically the Chicago Defender, continued to call the ballpark Schorling Park, even after John Schorling died in early 1940.

84 DeBono, 154.

85 Fay Young, “The Stuff Is Here,” Chicago Defender, May 17, 1941: 24.

86 DeBono, 155.

87 https://www.thecha.org/residents/public-housing/find-public-housing/wentworth-gardens. (Chicago Housing Authority).