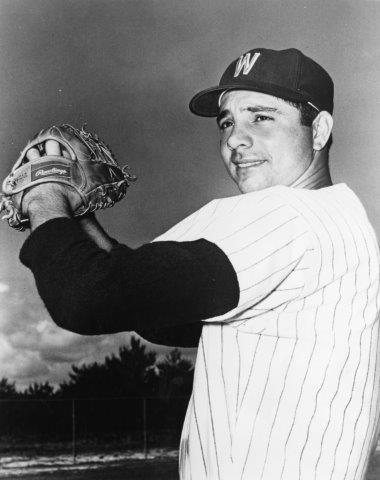

Rudy Hernández

It may surprise you to learn that by 1960 just two players born in the Dominican Republic had played in the majors: Ozzie Virgil and Felipe Alou debuted in 1956 and 1958, respectively. In 1960 they were joined by Julian Javier in the season’s second month. On July 3, 1960, Rudy Hernández became the first Dominican pitcher in the majors, a little more than two weeks before the famous Juan Marichal.

It may surprise you to learn that by 1960 just two players born in the Dominican Republic had played in the majors: Ozzie Virgil and Felipe Alou debuted in 1956 and 1958, respectively. In 1960 they were joined by Julian Javier in the season’s second month. On July 3, 1960, Rudy Hernández became the first Dominican pitcher in the majors, a little more than two weeks before the famous Juan Marichal.

Rodolfo Alberto Hernández Fuentes was born on December 10, 1930,1 in the city of Santiago de los Caballeros to Serafina Fuentes, a Puerto Rican, and Rubén Néstor Hernández Polanco. Rudy’s father was from nearby Tamboril.2 Rudy’s siblings, Rubén and Lourdes, were born 13 months before and after him, respectively. One branch of Rudy’s family tree has been traced back a few generations. A maternal great-grandmother, Barbara Fuentes, was a Puerto Rican slave freed no earlier than 1872. Rudy’s parents were reportedly married in New York City in 1926,3 though 1928 is indicated in the family’s entry in the 1930 US census. On April 10, 1930, the family of three was residing at 1171 Elder Avenue in the Bronx. Living with them were the elder Rubén’s brother, Amado, and 16-year-old brother-in-law, Paublo Villafane. Rubén was a bookkeeper for a bank and Amado’s job was cleaning for Interborough Rapid Transit, part of the New York City subway system.

The family returned to the Dominican Republic by the time Rudy was born. His parents eventually decided to raise their children in the United States. Serafina was adamant about not living in the Dominican Republic permanently so she returned to New York first and then her husband followed. Rudy was about 7 years old when the children moved to New York. His father later worked as an accountant for the Teamsters Union for many years.4 A New York passenger list for the S.S. Leif, which departed from Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic, on April 21, 1939, included Rodolfo Alberto Hernández Fuentes, age 8, traveling with his sister and parents. Based primarily on New York City phone books, from at least 1945 to 1960 the family’s residence was 803 West 180th Street in Manhattan.

Rudy had an uncle who was a military attaché at the Dominican embassy in Washington, Captain Juan Hernández. Rudy visited him often during the summer. After Hernández made his major-league debut in Washington’s Griffith Stadium, he told a Washington Post reporter he’d been there before with his uncle, who last took him there when he was 9 years old. His uncle’s chauffeur was a huge baseball fan and would take Rudy to watch the Senators play multiple afternoons in a row.5

Rudy attended Manhattan’s High School of Commerce, and box scores in April of 1947 showed a Hernandez in its baseball team’s lineup at first base.6 A year later he was one of 12 players featured in a team photo printed in the New York Post.7 In his first year as their center fielder, he had a batting average of .348,8 and the school later presented him an award named after Lou Gehrig, its most famous athletic alumnus.9 In 1948 Commerce’s baseball team finished second to Manhattan’s George Washington High School. Hernández continued on the team in 1949 and had one of his better games in a 6-5 loss to Newtown High, when he had three hits in four at-bats and scored twice.10

As a high-school athlete Rudy may have been as highly regarded for basketball as for baseball. He reportedly turned down a four-year basketball scholarship offered by Seton Hall.11 During the 1948-1949 school year Commerce’s basketball team was in the playoffs of New York City’s Public Schools Athletic League but lost in overtime on March 3, 1949, to Stuyvesant High. Naturally, media attention focused on the winning team. “Shoved into the background were the efforts of Rudy Hernandez and Herman Taylor with 17 and 14 markers, respectively,” wrote one reporter. “A story book one-hander from near mid-court by Hernandez four seconds before the end of the regulation time had extended the game an extra session.”12

Commerce’s team fared better the next school year, and it became something of a local legend by the late 1950s as its stars made names for themselves elsewhere, including Taylor, who played with the Harlem Globetrotters. Also on the 1949-1950 Commerce team was Frank Kasprzak, whose Holy Cross team won the NIT championship in 1954. Joining them was freshman Tony Windis, who later averaged over 20 points per game as a star at the University of Wyoming and played for the Detroit Pistons in 1960. Commerce’s team that season won 21 consecutive games on its way to winning the PSAL championship.13 Hernández was in Commerce’s lineup in November but wasn’t when they completed their amazing run in March.14 By the spring of 1950 he was signed to a contract by New York Giants scout Bubber Jonnard and was assigned to Class-D Oshkosh (Wisconsin State League).15

Opening Day for the Oshkosh Giants was May 4 in Appleton. At least one day before, Oshkosh manager Dave Garcia announced his starting lineup, and it included Hernández in center field.16

In his first official inning as a pro, Hernández was charged with a throwing error, but he made amends in the seventh inning. Appleton’s Merle Barth had doubled, and he tagged up on a long fly to center field. Hernández nailed him with “a perfect throw,” and the Appleton newspaper printed a photo of the double play as Oshkosh’s third baseman was “waiting for Barth to come in.” The game ended up being terminated after 13 innings, and the newspaper explained that tie wouldn’t count in the standings but all individual statistics did count. Hernández went hitless but stole a base.17

The two teams were supposed to meet again the next day but three league games were called off because of high winds.18 Thus, Hernández’s first hits as a pro came at home on May 6, 1950, against the Green Bay Bluejays. In a 17-14 win he had two hits in five at-bats and scored three times.19 Less than a week later, in an 8-1 victory over the same team, Hernández was the offensive star with four hits in five at-bats.20 The next month he was in the spotlight for two “sensational” defensive plays against the Janesville Cubs. “He covered a wide area like a tent to rob Pete Nitrini of a hit with a diving, one-handed catch in the second inning and to take a blow labeled for extra bases away from Joe Yambor in the fourth,” wrote the Janesville paper’s sports editor. “Hernandez raced to the fence in center-right to make an easy catch of Yambor’s hard smack.”21

Late in the season Hernández received a little media attention for an unusual reason. For Parker Pen Night in Janesville on August 17, a record crowd of almost 4,000 was entertained for an hour prior to the game. In addition to races and other contests involving players and umpires, there were musical performances. A quartet of Janesville Cubs performed two songs, as did “Rudy Hernandez, fleet center fielder of Oshkosh.”22

On September 2 the Oshkosh Giants clinched the pennant. “We won practically every honor that was possible to win that year,” Hernández recalled three years later.23 His batting average was just .241, but that figure excludes 10 playoff games in September. Oshkosh defeated Fond du Lac three games to one in the first round, and then Hernández became red-hot at the plate. He helped Oshkosh defeat Janesville in the finals, four games to two, with 8 hits in 18 at-bats, four runs scored, at least four walks, and an RBI, mostly batting eighth or seventh in the lineup.24

During the offseason Hernández played the first of many seasons in Puerto Rico’s winter league, for the team in Ponce. Each team was required to have a minimum number of Puerto Ricans on its roster, and he counted as one because his mother was born there. His manager was Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby, and he lived in the same building as future major leaguers Bill Skowron and Clint Courtney.25

For 1951 Hernández was promoted to Class-C St. Cloud (Northern League). His batting average improved to .262. “True, my hitting did pick up,” he commented in 1953, “but I wasn’t considered a notorious hitter by any stretch of the imagination.” Nevertheless, his skill as a fielder was clear, and he shared the team’s most valuable player honors.26

To start 1952 Hernández was promoted to Class-A Sioux City (Western League), where early on he was tried at second base.27 Hernández wasn’t hitting well after 20 games, and before mid-June he was with Class-B Sunbury (Interstate League). He broke his ankle sliding in a game on July 22 and was out for the rest of the season.28

Hernández spent all of 1953 with Class-B Gastonia (Tri-State League). At the beginning of the season he expressed concerns about plateauing. “I’ve been optioned out three times by the Giants,” Hernández said, “and I believe it’s time that I do something.” He was still committed to reaching the majors. “That’s simply why I’ve got to buckle down and make good here.” He also appeared to confess some overconfidence back in 1950. “I didn’t want to play Class D baseball, thought I knew all the angles,” he said regarding his assignment in Oshkosh. “As a matter of fact, I frankly believed I was ready for Class B ball, and, maybe, even Class A ball my first year.”29

Hernández performed very well early in the season for Gastonia. Team statistics in late May showed him with a batting average of .293 in 150 at-bats, and in mid-June two sportswriters with the Asheville Citizen-Times were advocating that he be named a league all-star.30 But Hernández slumped considerably in June and his average slid to .254 by the time he was “returned” to the New York Giants organization before the end of July.31 He then vanished from sports pages in August and September.

It was time to try a different approach, and that started in Puerto Rico’s winter league. Hernández’s first manager there, Rogers Hornsby, had pointed out a hitch in his swing, and at some point Hornsby recommended that he become a pitcher.32 For the 1953-1954 season in Puerto Rico, Phillies right-hander Steve Ridzik likewise encouraged him to try pitching. The person who ultimately convinced Hernández was Roberto Clemente. Clemente’s first season in Puerto Rico’s winter league was 1952-53,33 and he joked that because Hernández had struck him out, he could strike out anyone.34

As a new pitcher, for 1954 Hernández was sent back to Class-C Muskogee (Western Association). He won his first eight starts, and sportswriters throughout the league noticed. One paper in a banner headline trumpeted, “Undefeated Rudy Hernandez to Pitch Against Joplin at Muskogee Tonight.”35 He ended the season with a record of 15-4. He allowed just 7.1 hits per nine innings, thanks partly to four three-hitters.36 He also excelled at bat: .425 in 80 at-bats, and with five doubles, three triples, and five homers, his slugging average was .750.

In October The Sporting News reported that Hernández was to rejoin Class-A Sioux City in 1955.37 But his progress toward the majors was delayed by military service, which kept him from pitching for Sioux City until 1957. He didn’t play for any military team during his two years of active duty.38

Meanwhile, on September 23, 1956, Ozzie Virgil made his debut for the New York Giants and thus became the first Dominican-born player. “I knew it was a race to the line between Rudy and myself,” Virgil said 50 years later. “I had no idea I would be the first Dominican. The Dominican Republic had much better players than I was. I made a big jump that year.”39

Hernández was discharged in time to play in the 1956-57 Dominican winter league, for Escogido, along with Virgil and Felipe Alou.40 In April The Sporting News reported that he was assigned to Class-A Sioux City.41 He spent all of 1957 with Sioux City.

Early in the season Hernández made The Sporting News for his role in enforcing baseball’s unwritten rules, against the Lincoln Chiefs on May 7. The weekly wrote: “In the seventh, after Harry Williams homered for the Chiefs, Hernandez knocked down Roberto Sanchez, 5-6 Chief shortstop. With Hernandez at bat in the eighth, [Art] Murray backed him out of the box with four inside pitches and the Soo hurler rushed to the mound, swinging his bat. Other players prevented a scrap, but when the game was over Murray hit Hernandez with a flying tackle.42

Hernández’s best pitching performance of the season probably came on June 28, when he defeated Topeka 2-1, allowing only two singles.43 He won nine games and lost eight for the Soos, with a high earned-run average of 5.66. He started the 1958 season at Double A for the first time, Corpus Christi of the Texas League. But after four starts, with an 0-3 record and an ERA above 8.00, he was sent back to Class A, first Sioux City, the Springfield (Eastern League). His combined record with the three teams was a discouraging 0-9 with an ERA of 8.15. The Giants released him after the season.

In January of 1959 Hernández signed with the Miami Marlins, a Baltimore affiliate in the Triple-A International League.44 In April, before the season began, Miami sent him to Double-A Chattanooga in the Washington Senators organization.45

Hernández spent all of 1959 with the Chattanooga Lookouts. After his ninth game he sat comfortably atop the Southern Association’s ERA rankings at 2.21.46 However, he bruised his hand in New Orleans during early June when he was one of about 10 Lookouts who climbed into the stands to scuffle with some abusive fans. On June 8 he overcame his sore hand against New Orleans to take a two-hitter up to the final out, and hung on to defeat them, 4-1.47 After that he went seven weeks without a victory. On July 30 he finally won again, 5-1, in another rematch with New Orleans.48 In the end his record was only 8-12 but his ERA was a respectable 3.42. It proved to be his last pro season as a starting pitcher.

For 1960, at long last Hernández made it to Triple A, with the Senators’ American Association team in Charleston. In 31 appearances through June, all in relief, his ERA was 2.70. A potential setback then turned out surprisingly well: “Charleston Senators ace reliever Rudy Hernandez has come up with a sore arm and is on his way to Washington, D.C., for treatment by the Washington Senators’ club physician,” the Charleston Gazette reported on July 2. “There’s a chance, if Hernandez’ arm comes along okay, that Washington may keep him and add him to its major league roster.”49 That chance turned into reality, and on July 3, 1960, Rudy Hernández became the first Dominican-born pitcher in the major leagues.

That day the Senators hosted the Cleveland Indians for a doubleheader. In the first game Senators starter Bill Fischer gave up five runs in the first five innings. Manager Cookie Lavagetto summoned Hernández in the top of the sixth inning. The first Cleveland batter he faced was Chuck Tanner, who grounded out to second. He walked the third batter but struck out the fourth to end the inning. In the seventh inning he retired the Indians 1-2-3, all on fly outs to center field. In the eighth inning he gave up a single but for the second time faced only four batters. The Senators lost the game, but Hernández had a very good debut.

Less than a week later, on July 9, Hernández earned his first win in the majors, against Baltimore. The game was tied 2-2 in the bottom of the seventh when Senators starter Hal Woodeshick yielded singles to the first two Orioles. Hernández relieved and the first batter he faced sacrificed. The next batter was walked intentionally to load the bases with one out. Hernández coaxed Gene Woodling to pop out into foul territory, then struck out Gene Stephens looking to end the threat. The Senators followed with a five-run outburst, and Hernández had little difficulty in the final two innings.

Hernández notched his second victory against the White Sox at home on July 29, his third on August 8 in Kansas City, and his fourth on August 14 in Yankee Stadium, not far from where he grew up. In the latter contest, the Senators had already won the first game of a doubleheader. The Yankees tied the nightcap at 3-3 in the bottom of the ninth inning. Hernández pitched the 13th and 14th with leadoff baserunners getting nowhere in either inning. The Senators scored three in the top of the 15th, and Chuck Stobbs earned a save in the bottom half of the frame to end it. After six weeks, the rookie’s record stood at four wins, no losses. Hernández suffered his only loss of the season at home to Chicago on August 30. He pitched in 21 games overall.

The Senators relocated to Minnesota and became the Twins in 1961, but a new Washington franchise was created as the American League expanded from eight teams to 10 (with the other new one being the Angels). The new Senators selected Hernández from the previous Senators in the expansion draft. Hernández, pitching for Ponce in Puerto Rico, said, “This is the best baseball news I ever have gotten in my life. It gives me confidence.”50 In mid-February of 1961 it was announced that he had agreed to terms with his new club.51

On April 10, 1961, Hernández experienced Opening Day on a major-league roster as the new Senators played their first official game, at home against the White Sox. He pitched in his final major-league game less than a month into the season. It was at home on May 4 versus the Tigers. The last batter he faced was Al Kaline, whom he threw out at first base on a grounder. It was his seventh appearance, and he ended it with a good 3.00 earned-run average, but he was a victim of unique circumstances. Each team had been allowed 28 players on its roster during the season’s opening month, and Hernández was one of three players optioned to Triple A in order to reach the 25-player limit.52

For the remainder of 1961 through 1964 Hernández continued to pitch in the minor leagues, almost always at the Triple-A level, in several major-league farm systems. He continued to play in Caribbean winter leagues even longer.53 After the 1964 season he retired as a player. He has two daughters, Maria Veronica “Vicky” Hernández and Jennifer Muñoz, though he never married.54

By 1971 Hernández was operating a bar in San Juan, Puerto Rico, called Rudy’s 10th Inning Lounge.55 After his site was sold, he opened another lounge, Rudy’s on the Beach.

When an earthquake struck Nicaragua in late 1972 and Roberto Clemente coordinated humanitarian aid in Puerto Rico, Hernández had a modest role in the relief effort and thus was interviewed at length about Clemente’s death on December 31, 1972, when a plane loaded with relief supplies crashed. “On the final morning of Roberto Clemente’s life, Rudy Hernandez was in his bar and suddenly remembered the ‘mercy kettle,’” wrote sportswriter Jerry Izenberg, in the Newark Star-Ledger.

“It was a big iron pot and people were throwing money in it for the earthquake victims since the relief campaign began. They would have put money into any cause Roberto was behind,” Hernández told Izenberg. “I called the house to find out what to do with it and [his wife] Vera told me he was asleep, but I remembered he wanted it to go to Nicaragua to show the people how much we cared.”

“I told her I would send Manny (Sanguillen) to the airport with it,” Hernández told Izenberg. “The day before, Roberto had stopped by the bar and I remember I urged him not to go because it would be New Year’s Eve. But he said, ‘If I don’t, who will?’” Hernández also spoke at length at how Clemente’s death devastated Puerto Ricans.56

A few years later Hernández shuttered Rudy’s on the Beach and went to work for Puerto Rico’s Department of Sports and Recreation. For more than 25 years he was a baseball instructor for youth of the inner city and housing projects in and around San Juan, and then retired there. Hernández has had other connections to baseball, including scouting for the Cubs and Orioles. He focused more on reporting than on trying to help sign players. When Orlando Cepeda started a baseball school in the late 1970s near San Juan, Hernández became one of the instructors.57

Hernández has two daughters, Maria Veronica “Vicky” Hernández and Jennifer Muñoz.58

As an instructor Hernández could share life lessons with athletes he tutored. He could speak from personal experience about not being discouraged by setbacks. Perhaps more importantly, he could testify credibly about setting high goals while also not being reluctant to change your plans.

Last revised: October 29, 2022

Notes

1 Almost all sources instead identify 1931 as the year of Hernández’s birth, although it is shown as 1933 on his 1961 Topps baseball card. When he re-entered the United States from the Dominican Republic on January 29, 1960, his year of birth on the passenger list was 1930 (with his longtime address of 803 W. 180th St., N.Y., confirming that it wasn’t some other Rudy Hernández). His nephew Rubén Hernández provided to the author a photo of Rudy’s current passport, which also shows 1930 as his year of birth.

2 Cuqui Córdova, “Béisbol de Ayer: Rudy Hernández,” Listín Diario (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), July 5, 2008: listindiario.com/el-deporte/2008/07/05/64968/beisbol-de-ayer. Córdova devoted his weekly Béisbol de Ayer columns to different phases or aspects of Hernández life during July and August of 2008.

3 Genealogy Report: Descendants of Maria Rosario, genealogy.com/ftm/u/h/l/Jaimee-E-Uhlenbrock-NY/GENE1-0004.html; details about “Rudi” and Serafina Fuentes are on the same web page, while details about Barbara Fuentes are on the second page. Jaimee Uhlenbrock, Professor Emerita of the State University of New York, New Paltz, in email to the author on July 9, 2018, noted that details on the home page, about Barbara Fuentes’ mother were due for substantial revision and thus should be discounted.

4 Email to the author from Rubén Hernández, October 28, 2016.

5 Bob Addie, “Bob Addie’s Column,” Washington Post, July 5, 1960: A15; Bob Addie, “Pitcher Hernandez and Chauffeur Often Watched Senators Play Here,” Washington Post, March 7, 1941: A16. Regarding Rudy’s parents, Thomas E. Van Hyning (see Note 25) said, “His father was the son of [dictator Rafael] Trujillo’s top general in the Dominican military.” However, in email to the author on July 5, 2018, Rudy’s nephew Rubén said that may be confusing Rudy’s uncle Juan, the captain, with Rudy’s paternal grandfather. Rubén added that Rudy’s father also served in the Dominican military though with a rank likely no higher than master sergeant. He also noted that Rudy’s aunt Margarita, wife of the aforementioned uncle Amado Hernández, was sister of a Dominican president, but that was Joaquín Balaguer and not Trujillo. Amado and Margarita had a daughter, also named Margarita, who served as secretary of state for her uncle Joaquín. She and cousin Rudy kept in touch often.

6 “Flushing Wins over Commerce by 9-0 Score,” Long Island Star-Journal, April 9, 1947: 14; “Jamaica Leads in Short Game,” Long Island Star-Journal, April 15, 1947: 12. The latter game was rained out about halfway through the fourth inning but the newspaper printed the stats anyway. In the earlier game Commerce managed only three hits, one of them by Hernández.

7 New York Post, April 22, 1948: 42.

8 Cuqui Córdova, “Béisbol de Ayer: Rudy Hernández,” Listín Diario (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), July 12, 2008: listindiario.com/el-deporte/2008/7/12/65826/Beisbol-de-ayer.

9 Addie, “Pitcher Hernandez.”

10 “Jamaica Plays Tie with Commerce,” Long Island Star-Journal, March 29, 1949: 13; “Newtown Nine Scores, 6-5,” Long Island Star-Journal, April 5, 1949: 13. It was in the former article that Commerce was referred to as “runner up last year to George Washington in Manhattan.”

11 Ken Alexander, “Ken’s Pen: Three Years under Giant Option[,] Rudy Figures This Is Do or Die,” Gastonia (North Carolina) Gazette, May 2, 1953: 14.

12 “Bryant Five Bows in PSAL Playoffs,” Long Island Star-Journal, March 4, 1949: 17.

13 “Easy-Going Cowboy Star Getting Raves,” Uniontown (Pennsylvania) Morning Herald, January 30, 1958: 11. The article focused on Windis but noted his connection to Taylor, Kasprzak, “and Rudy Hernandez, who last year received $9,500 for signing to pitch for a New York Giant farm team.”

14 “Cagers Warm Up as Football Fades,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 16, 1949: 27. The box score’s lineup included Taylor, Hernández, and Kasprzak. Hernández wasn’t in any of the Commerce lineups printed in the New York Times on March 3, March 14, and March 19. The same is true for “Commerce Five Wins School Final, 67-50,” New York Times, March 24, 1950: 34.

15 Alexander: 14.

16 “Champion Oshkosh ‘9’ Invades Goodland Field Thursday Night,” Appleton (Wisconsin) Post-Crescent, May 3, 1950: 26.

17 Orv Wonser, “Only 863 See Papers, Giants in Thrilling 13-Inning 5-5 Tie,” Appleton Post-Crescent, May 5, 1950: 17, 19.

18 “Friday Night’s Results,” Appleton Post-Crescent, May 6, 1950: 11.

19 “Bluejays Drop 2 to 1, 13-Inning Thriller on Error at Oshkosh; Lose Opener by 17 to 14,” Green Bay Press-Gazette, May 8, 1950: 17. Garcia was the big star, setting a league record with nine RBIs.

20 “Appleton Hurler Fans 19 Fondy Batters; Papermakers Cop 14-3,” La Crosse (Wisconsin) Tribune, May 13, 1950: 6.

21 George Raubacher, “Cubs’ All-Star Hopes Given Boost by Fond du Lac,” Janesville (Wisconsin) Daily Gazette, June 26, 1950: 12.

22 “Sports Hash,” Janesville Daily Gazette, August 18, 1950: 10. Elsewhere on the page the paper said 3,996 were in attendance.

23 Alexander: 14. The only other Oshkosh player to reach the majors was pitcher Joe Margoneri, with the Giants in 1956 and 1957.

24 See box scores in Janesville (Wisconsin) Daily Gazette, September 11 through 16, 1950, on pages 11, 12, 10, 6, 11, and 10, respectively.

25 Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League: A History of Major League Baseball’s Launching Pad (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1995), 121.

26 Alexander: 14.

27 Alex Stoddard, “Soos May Be in Thick of W.L. Race,” Beatrice (Nebraska) Daily Sun, April 14, 1952: 3.

28 “Caldwell First to Post No. 15,” The Sporting News, August 4, 1952: 34.

29 Alexander: 14.

30 “Report on Rockets,” Gastonia Gazette, May 30, 1953: 12: Ken Alexander, “Ken’s Pen,” Gastonia Gazette, June 18, 1953: 22.

31 “Deals of the Week,” The Sporting News, July 29, 1953: 31.

32 Van Hyning, 121.

33 Van Hyning, 53-55.

34 Email to the author from Rubén Hernández, October 28, 2016.

35 “Undefeated Rudy Hernandez to Pitch Against Joplin at Muskogee Tonight,” Joplin (Missouri) News Herald, June 9, 1954: 2B.

36 “Chico Hernandez Stops Joplin on Three Hits as Giants Win, 12-2,” Joplin (Missouri) Globe, April 27, 1954: 8; “Elks in Comeback after Three Losses,” Hutchinson (Kansas) News Herald, June 10, 1954: 2; “Elks Lose to Iola Indians,” Hutchinson News Herald, June 29, 1954: 2; “Elks in Split with Giants,” Hutchinson News Herald, July 30, 1954: 2. Hernández homered in the first of these two games. In the first of these articles it was indeed implied that Rudy had been given the nickname “Chico.”

37 “Deals of the Week,” The Sporting News, October 20, 1954: 28.

38 Email to the author from Rubén Hernández, October 28, 2016.

39 “Virgil Celebrates 50th Anniversary” Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), September 22, 2006: C2.

40 Joe King, “Stoneham Seeks Another White in Dominican Loop,” The Sporting News, November 28, 1956: 21; Félix Acosta Núñez, “Lopat Takes Hill, Helps U.S. Stars Decision Natives,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1957: 20.

41 “Deals of the Week,” The Sporting News, April 2724, 1957: 34.

42 “Three Hits, Seven RBIs,” The Sporting News, May 15, 1957: 37.

43 “Sioux City Tops Topeka Twice,” Albuquerque Journal, June 29, 1957: 15.

44 “Miami Goes South for More Talent,” Findlay (Ohio) Republican Courier, January 29, 1959: 17. Proof that this wasn’t some other player with the same name was provided by Luther Evans, “Marlins Deflated in Opener,” Miami Herald, March 23, 1959: C1, when he was referred to as “Rudolph Albert Hernandez … former outfielder.” See also Eddie Storin, “Indianapolis Mauls Marlins Again,” Miami Herald, April 3, 1959: 2C. The latter reported on a game in which “Rudy Hernandez was fairly effective, limiting the American Association Indians to one run on one hit and three walks in two innings.”

45 “Deals of the Week,” The Sporting News, April 22, 1959: 28.

46 “Dixie Averages,” The Sporting News, May 27, 1959: 35.

47 “Lookouts’ Kaat Back in Form,” The Sporting News, June 17, 1959: 33.

48 “Bradey Has 5.01 ERA, Wins 15,” The Sporting News, August 12, 1959: 35.

49 “Sore Armed Hernandez Leaves Sens,” Charleston (West Virginia) Gazette, July 2, 1960: 9.

50 “5 Drafted by Nats Pleased with Pick,” Findlay (Ohio) Republican Courier, December 16, 1960: 25.

51 Bob Addie, “New Nats Will Start Wednesday,” Washington Post, February 19, 1961: C1. Hernández became very fond of his new manager, Mickey Vernon, according to an email to the author from his nephew, Rubén Hernández, October 28, 2016.

52 Mike Rathet, “Major League Cutdown Time at Midnight,” Corpus Christi (Texas) Caller-Times, May 10, 1961: 21.

53 For example, see Miguel J. Frau, “Pity Crabbers! Even Weather Adds to Woes,” The Sporting News, November 20, 1965: 29.

54 Email to the author from Rubén Hernández, October 28, 2016.

55 Thomas E. Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers: Sixty Seasons of Puerto Rican Winter League Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1999), 118.

56 Jerry Izenberg, “It Was the Night the Happiness Died,” Newark Star-Ledger, December 30, 2002: 39.

57 Email to the author from Rubén Hernández, October 28, 2016.

58 Email to the author from Rubén Hernández, October 28, 2016.

Full Name

Rudolph Albert Hernandez Fuentes

Born

December 10, 1931 at Santiago, Santiago (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.