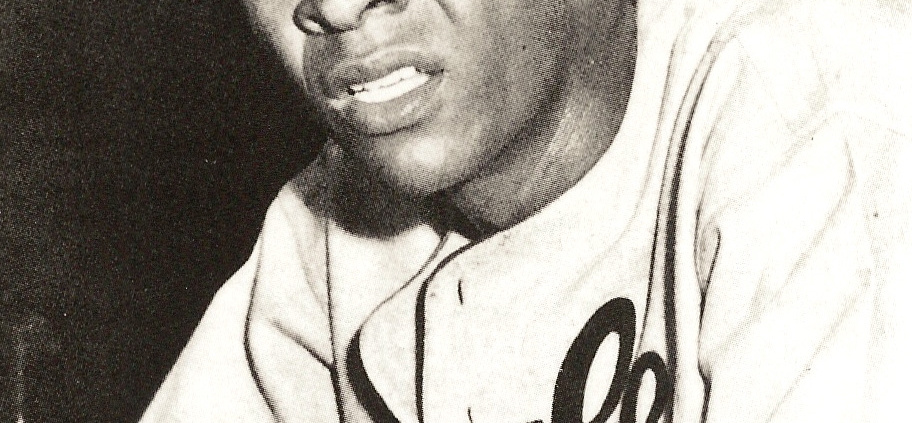

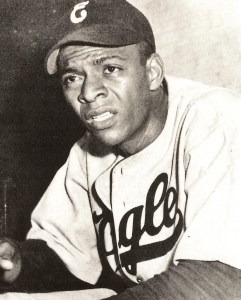

Rufus Lewis

There is nothing more exhilarating or more intoxicating in baseball than the seventh game of a best-of-seven championship series. It is an unforgiving arena where history is written of both the heroes who carry the day and their vanquished opponents. Winning pitchers in a game seven instantly become legends not only to their own team’s fanbases, but to the sport’s broader history as well. Johnny Podres pitched in four World Series in his 15-year career, but it was his 2-0 shutout of the New York Yankees in Game Seven of the 1955 World Series that cemented his fame in Brooklyn long after Ebbets Field came down. Jack Morris was the ace of the Tigers in the 1980s and led them to a World Series crown in 1984, but it was his 1-0, 10-inning triumph in 1991’s Game Seven for the Minnesota Twins that was perhaps the tipping point that led to his 2018 enshrinement in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

There is nothing more exhilarating or more intoxicating in baseball than the seventh game of a best-of-seven championship series. It is an unforgiving arena where history is written of both the heroes who carry the day and their vanquished opponents. Winning pitchers in a game seven instantly become legends not only to their own team’s fanbases, but to the sport’s broader history as well. Johnny Podres pitched in four World Series in his 15-year career, but it was his 2-0 shutout of the New York Yankees in Game Seven of the 1955 World Series that cemented his fame in Brooklyn long after Ebbets Field came down. Jack Morris was the ace of the Tigers in the 1980s and led them to a World Series crown in 1984, but it was his 1-0, 10-inning triumph in 1991’s Game Seven for the Minnesota Twins that was perhaps the tipping point that led to his 2018 enshrinement in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

While Podres and Morris are rightly remembered as Game Seven heroes, the name Rufus Lewis has largely been lost to history. His game seven résumé equals that of Podres and Morris, but due to baseball’s former adherence to the practice of segregation, his exploits have been largely lost to history. But his career demands more. Lewis not only pitched the Newark Eagles to the Negro World Series crown in 1946, he won championships with teams around the world while competing with and against some of the greatest players in the history of the game. He served his country with distinction during World War II, during the prime years of his career, and was named to all-star teams that played in the nation’s largest stadiums. His career typifies those of so many other pre-integration African-Americans who starred on Negro League diamonds but were forbidden to compete on the game’s greatest stage due to the color of their skin.

Rufus Lewis was born on December 13, 1919, in the tiny town of Johnstons Station, Mississippi, a railroad stop between Jackson, Mississippi, and New Orleans an hour west of Hattiesburg.1 He was the first of four children born to Robert and Mary Beatrice (Williams) Lewis. Thefamily migrated north to the more urban setting of Jackson in the 1920s. Census records from 1940 list Lewis as a sophomore at Jackson State University. As with most young American men in the 1940s, Lewis’s life was changed by the United States’ entry into World War II. He registered for the draft in early 1942.2 He began his tour of duty as an enlisted man in the Army in 1943, serving through 1945 before being discharged. His military obligation completed, Lewis turned his attention back to baseball. His baseball life featured peaks and valleys, as do most players’ careers, but the extremes Lewis experienced on both sides of the spectrum during his playing days tell the story of a man who saw it all on the diamond.

Lewis’s big break came after the war when he was scooped up by Effa Manley’s Newark Eagles, perennial bridesmaids in the Negro National League, for the 1946 campaign. The star-studded roster featured Larry Doby and Monte Irvin patrolling the infield for Newark while Lewis joined Leon Day and Max Manning to anchor the Eagles’ pitching staff. Lewis was discovered in the spring of 1946 by Eagles skipper Biz Mackey. Mackey saw potential greatness in the young hurler stating that not only did Lewis possess a great breaking ball, he also had a fastball that was, “[as] speedy as the unpredictable Satchell in his prime.”3 Mackey, a catcher, took Lewis “under his personal supervision” as Lewis prepared to make his NNL debut.4

Lewis took the mound for Newark on May 18 against the Homestead Grays. He struggled through a three-run first inning, but he settled down to record seven strikeouts over four innings in a game that was eventually rained out.5 On May 22, Lewis earned his first victory for the Eagles against the Philadelphia Stars as he handed them a 5-2 loss.6 Lewis opened June pitching “brilliant ball” in a 4-2 victory over the Elite Giants.7 As the Eagles battled down the stretch, Lewis continued to shine. On August 25, Lewis ran his record to 8-1 with a 12-5 win over the Homestead Grays in Newark and chipped in with a double of his own.8 So dominant were the triumvirate of Day, Manning, and Lewis that, in the words of Baltimore pitcher Frank Duncan, “I think [they] went two or three months and a relief pitcher didn’t get off the bench.”9 During the regular season, Lewis went 9-3 with 64 strikeouts. The Eagles defeated the Cuban Stars in early September at Ruppert Stadium in Newark to capture the NNL pennant and earned a berth in the Negro World Series against the legendary Kansas City Monarchs. It was this series that saw Lewis reach the pinnacle of his playing days as he stared down Satchel Paige and the Monarchs and refused to blink.

Lewis featured three times in the 1946 Series, the first appearance in relief of Leon Day in a 2-1 Game One loss. Though Lewis pitched well, scattering four hits and one run in four innings of work, Paige came on in relief to outduel him and also sparked the game-winning rally with an infield hit to open the seventh.10 Getting tagged with the loss in the Series opener might have crushed the spirit of a lesser pitcher, but Lewis was made of sterner stuff. The right-hander was given a tall assignment for his next Series outing, a Game Four start with the Monarchs seeking to take a commanding three-games-to-one lead in their home stamping grounds of Kansas City. With the spotlight on him, Lewis delivered a gem. He gave up a second-inning run to the Monarchs, but shackled them the rest of the way as the Eagles knocked Ted Alexander out of the box early en route to an 8-1 Series-tying triumph.11 Lewis’s performance evened the series at two games apiece. His next game would turn into the biggest one of his career.

Though the Monarchs and Eagles had split Games Five and Six to force a deciding seventh game, Eagles pitchers Max Manning and Leon Day had struggled. Manning had dropped a 5-1 decision to Kansas City in Game Five and though they won Game Six, Day was shelled early for five runs. Neither man was in form heading into the final tilt, so Eagles boss Biz Mackey went with the hot hand. Lewis got the nod for Game Seven. Mackey and the Eagles would not regret the decision.

The Eagles drew first blood in the bottom of the first inning when Pat Patterson reached on an error and scored an unearned run. Lewis, who scattered eight hits throughout the game, held the lead until the sixth inning. In the top half of the frame, Lewis made a mistake to Buck O’Neil, who crushed a game-tying home run into the left-field stands. Newark immediately struck back in the bottom half when Johnny Davis clouted a two-run double to stake the Eagles to a 3-1 lead. Kansas City answered in the seventh on an RBI single by Herb Souell that cut the lead in half, but Lewis escaped the inning with no further damage. A scoreless eighth inning left Newark clinging to a one-run lead, and Mackey sent Lewis out to pitch the ninth and capture the crown.12

Lewis rode his luck to open the ninth. Monarchs catcher Earl Taborn laced a single to right-center to lead off the inning, but he was gunned down at second base by center fielder Jimmy Wilkes. This play loomed large as the inning progressed and Kansas City put runners on second and third with two out and Herb Souell again in a position to drive in a run. This time, Lewis got the upper hand. Souell lofted a lazy popup to Lennie Pearson for the final out of the game, and Newark erupted with joy. Eagles owner Effa Manley, watching from the stands with her “head down, eyes closed, arms crossed, and unable to watch,” slumped in her seat with relief as those around her offered congratulations on the team’s first World Series crown.13 Manley owed her “hour of triumph” to Lewis.14 Over two pressure-packed games, Lewis scattered 12 hits and three runs over 18 innings of work. Overnight, Rufus Lewis was a hero to the Newark faithful.

Lewis’s Series performance earned him a berth on the barnstorming circuit in the 1946-47 offseason. Satchel Paige, Lewis’s World Series foe, signed the young star to feature with his all-star team in games throughout the country.15 Paige, ever a showman with an eye on the box office, no doubt was glad to have the red-hot Lewis on his roster. Lewis pitched for the Eagles in 1947 and 1948 and in both seasons did well enough to be tabbed the starting pitcher for the East in the East-West Game. Though he took the loss in both all-star stints, his presence in the starting lineup serves to show how respected Lewis was among Negro League moundsmen during his heyday. Lewis spent both winters in the Cuban League with the Habana Leones, for whom he “had a great campaign on the mound” during their 1947 championship season.16 By 1950, Lewis was plying his trade south of the border in the Mexican League. It was there that he was involved in an on-field incident that nearly cost him his life.

During a regular-season game in 1950, Lewis was pitching for Mexico City against Jalisco. The batter he was facing was no slouch. Adolfo Cabrera of Jalisco was the loop’s leading hitter the year before with a .379 average in 1949.17 He was also a man with a temper. The day before, Cabrera got into an altercation with the Mexico City shortstop and had to be separated from his opponent.18 Against Lewis, the situation became far more deadly. Lewis hit Cabrera with a pitch, a curveball that didn’t break. Cabrera started toward first base, bat in hand, and then sprinted toward Lewis and hit him with the bat, knocking Lewis senseless to the ground. Cabrera raised the bat overhead to strike Lewis, a blow that would have likely killed the pitcher, according to those present.19

Lewis’s life was saved by the quick reactions of teammate Wild Bill Wright. Wright sprinted from the dugout, his own bat in hand, and used it to split open Cabrera’s scalp to end the fracas. Wright’s heroics kept Cabrera out of serious legal trouble. Had he landed the second blow, Cabrera “(would have) been put in jail for life,” according to league President Jorge Pasquel.20 For his part, Lewis denied throwing at Cabrera deliberately.21 The facts seem to support Lewis’s position. No pitcher wishing ill intent toward a hitter would use a curveball to do the job. Further, there was some disagreement by players whether Cabrera had been struck by the pitch at all. Wright stated that while Cabrera may have been brushed by the pitch, the ball carried all the way to the backstop as if it had done the batter no physical harm.22 In any case, the incident was firmly etched in the memories of everyone present.

The affair with Cabrera was without doubt the low point of Lewis’s on-field career. He caught on in 1952 with the Chihuahua Dorados of the Class-C Arizona-Texas League, but it was too late in the game for Lewis. His 8-15 record that season belied the brilliance he had shown with Newark, and his time in Organized Baseball came to a close. As with all former Negro League players, one is left to wonder if he could have pitched in the major leagues while in his prime. He was actively scouted by major-league teams during the 1946 World Series, but was never signed.23 As historian Rob Ruck argues, baseball’s informal quota system was working against Lewis. Younger, all-star-caliber players like Larry Doby and Monte Irvin were snatched up quickly by big-league clubs while older journeyman players such as Lewis were left behind to toil overseas or in the low minors.24 Lewis retired from the game to the Detroit suburbs, where he lived until his passing in Southfield on December 17, 1999, shortly after his 80th birthday.

The career of Rufus Lewis is one that deserves greater recognition. His exploits in the 1946 Negro World Series led the Newark Eagles to their only championship season. He squared off against some of baseball’s most legendary players and came out on top. His clutch pitching skills were recognized by Satchel Paige when he asked Lewis to pitch alongside him on his barnstorming tour against all-star aggregations, and he was named to the East-West Game on two occasions, both as a starter. Jim Crow’s legacy has left Lewis’s career largely forgotten by modern baseball fans as is the case with countless other Negro League stars. Even when his name is spoken, the Mexico City attack is the most enduring story attached to his name. However, when recalled by those watched and played with him in Newark, Havana, and all points in between, Rufus Lewis is remembered best as a guy who pitched on the greatest stages available to him and excelled.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and the US Federal Census via Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 World War II Draft Registration Card fold3.com/image/607831679 (accessed December 1, 2018).

2 Ibid.

3 “Fast Pitcher With Eagles,” Sunday Call (Newark, New Jersey), April 14, 1946.

4 Ibid.

5 “Eagles-Grays Tilt Halted in Sixth Knotted at 3-All,” Sunday Call, May 18, 1946.

6 “Eagles, Philly Split 2 Games; 7-1, 5-2” Newark Journal and Guide, May 25, 1946.

7 “Eagles Are Victors Twice In Road Tilts,” Newark News, June 6, 1946.

8 “Eagles Continue Race to NNL Flag With 2 Victories,” New Jersey Afro American, August 31, 1946.

9 Brent Kelley, Voices from the Negro Leagues: Conversations with 52 Baseball Standouts (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing, 1998), 170.

10 “Eagles Bow,” Newark News, September 18, 1946.

11 “Series Is Tied as Eagles Win,” Newark News, September 25, 1946.

12 “Eagles Hit in Clutches,” Newark News, September 30, 1946.

13 Bob Luke, The Most Famous Woman in Baseball: Effa Manley and the Negro Leagues (Washington: Potomac Books, 2011), 1.

14 Ibid.

15 Rufus Lewis, nlbpa.com/the-athletes/lewis-rufus (accessed December 7, 2018).

16 Roberto Gonzalez Echevarria, The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 54.

17 James A. Riley, Of Monarchs and Black Barons: Essays on Baseball’s Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing, 2012), 229.

18 Kelley, 30.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Riley, 229.

22 Kelley, 30.

23 “Majors to Scout Eagles’ Series,” Sunday Call, September 15, 1946.

24 Rob Ruck, Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001), 108.

Full Name

Rufus Lewis

Born

December 13, 1919 at Johnstons Station, MS (US)

Died

December 17, 1999 at Southfield, MI (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.