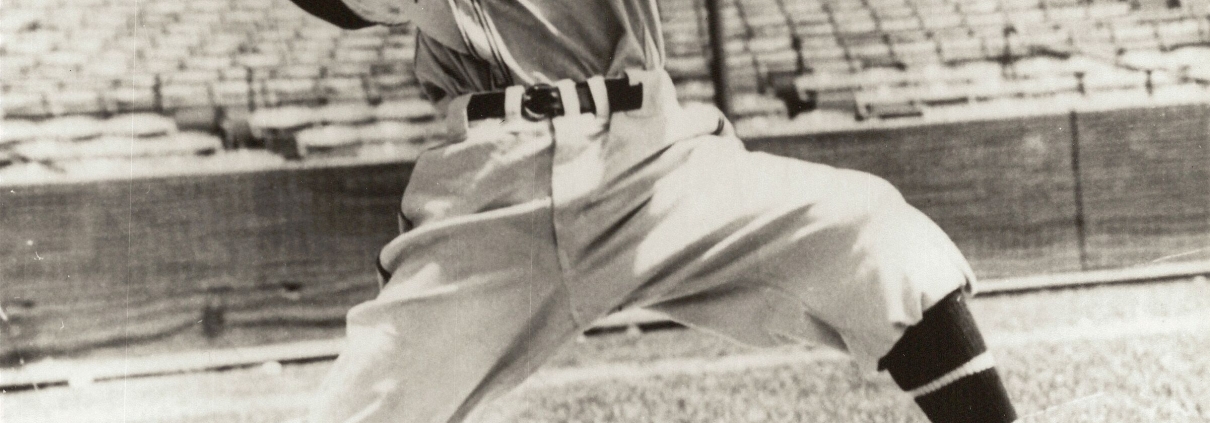

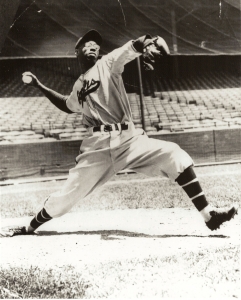

Maxwell Manning

Max Manning was a man of many nicknames. Newark Eagles teammate Jimmy Hill gave him the moniker Dr. Cyclops, by which he became best-known in baseball circles. Hill had just seen the 1940 movie with that title, but he could not recall seeing any other player who wore glasses — especially thick spectacles like Manning’s — so the name seemed fitting to him.1 Eagles co-owner Abe Manley, Manning’s longtime employer, developed such a good rapport with him that he called him Milio — a contraction of the name Maximilian (though that was not Manning’s full first name) — so he also became known by that sobriquet.2 In Cuba, where Manning played four seasons, he was called Profesor,3 in reference to the scholarly appearance that his glasses bestowed upon him; this particular nickname became most apropos as Manning went on to a lengthy career as a teacher once his tenure as a star pitcher in the Negro and Latin American baseball leagues ended.

Max Manning was a man of many nicknames. Newark Eagles teammate Jimmy Hill gave him the moniker Dr. Cyclops, by which he became best-known in baseball circles. Hill had just seen the 1940 movie with that title, but he could not recall seeing any other player who wore glasses — especially thick spectacles like Manning’s — so the name seemed fitting to him.1 Eagles co-owner Abe Manley, Manning’s longtime employer, developed such a good rapport with him that he called him Milio — a contraction of the name Maximilian (though that was not Manning’s full first name) — so he also became known by that sobriquet.2 In Cuba, where Manning played four seasons, he was called Profesor,3 in reference to the scholarly appearance that his glasses bestowed upon him; this particular nickname became most apropos as Manning went on to a lengthy career as a teacher once his tenure as a star pitcher in the Negro and Latin American baseball leagues ended.

Maxwell Cornelius Manning was born on November 18, 1918, in Rome, Georgia. He was the second son born to Robert W. and Helen (Burrell) Manning. The family eventually grew to include not only Max and his older brother Robert Jr., but also younger siblings Helen, Marilyn, John, Loretta, and Richard.

Manning was named after his grandfather, Cornelius Maxwell Manning, who had a distinguished past. Rev. C. Maxwell Manning, as he later became known, was born in 1845 and, at the age of 18 joined the 35th Regiment of the US Colored Infantry in North Carolina during the Civil War. Over the course of his three-year enlistment, he fought in a number of skirmishes in Florida.4 After his wartime hitch ended, Manning became a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1896 President Grover Cleveland named him secretary of the US Legation in Liberia, a country that had been founded as a settlement in 1822 with the express purpose of resettling freed slaves from North America; he was recalled from that position by President William McKinley in 1898.5 Rev. Manning’s second son, Robert, was born in 1889 and studied to become a teacher. Robert’s son, Maxwell — a.k.a. Profesor — eventually followed in his father’s footsteps.

Manning had no memories of Rome, Georgia, as his family moved to Mississippi not long after his birth when his father took the job of head schoolmaster at the Vicksburg Industrial School.6 The 1920 Census shows that the Manning family lived in a rural area of Hinds County, Mississippi, which is next to Warren County, where Vicksburg is located. The Jim Crow South was a harsh environment for African-Americans, and Hinds County had the highest rate of lynching of black people in Mississippi between 1877 and 1950.7 Although Manning was too young to know how great a role the extreme prejudice his family encountered in the South may have played in his father’s decisions, the family soon moved to Philadelphia, and shortly thereafter settled in Pleasantville, New Jersey.

By the time Manning attended Pleasantville High School, his talents were such that he became the only black player on the school’s baseball team. Ty Helfrich, a second baseman for the Federal League’s Brooklyn Tip-Tops in 1915, was the team’s coach. Helfrich “saw potential in Max and helped him to develop into an excellent high school pitcher.”8 Manning credited Helfrich with helping him to develop his fastball. He also said that Helfrich was the person who first told him he believed Manning could make a good living as a pitcher in the Negro Leagues. According to Manning, Helfrich “went on to tell me about them, how he had played against the House of David and all those different clubs. He said that they do pretty good and not only that, they have a chance to go to other countries and play.”9 Helfrich turned out to be equal parts encourager and prophet.

While he was still in high school, Manning also played for the semipro Johnson’s All-Stars, a team coached by the legendary John Henry “Pop” Lloyd, in Atlantic City. Lloyd is still considered by many to have been the top shortstop ever to play in the Negro Leagues, and he was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1977. Manning said of Lloyd, “Pop taught me many things about baseball, how to play and conduct myself off the field.”10 Besides playing for Johnson’s All-Stars, Manning also played for the Camden Giants, a team that he said “had old timers who had played in black leagues.”11

Manning developed his pitching skills so well — and filled out an intimidating 6-foot-4 frame — that he was offered a contract by Detroit Tigers scout Max Bishop upon his graduation in 1937. Bishop — who ironically was known as Camera Eye for his ability to locate pitches as a batter — had never actually seen Manning, so he did not know that his prized pitching prospect was black. Manning laughed as he recalled in an interview:

My father brought me up against the wall and said, “Look. Let me tell you something. You’ve got to face real life here. You’ve got about as much chance of playing for the Detroit Tigers as a snowball in hell. … You’ve seen pictures of ballplayers and you don’t see any there your color, do you?”12

Once Bishop found out about Manning’s race, he immediately rescinded his offer. As the elder Manning had observed, the major leagues were not yet ready for black players.

In the fall of 1937 Manning enrolled at Lincoln University in nearby Oxford, Pennsylvania. He played on the school’s baseball and basketball teams, and it was there that he met his lifelong friend, future Newark Eagles teammate, and eventual Hall of Famer Monte Irvin. Manning finished one year at Lincoln before both he and Irvin were approached by Abe Manley, who wanted them to play for the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League. Although both players signed with the Eagles late in the 1938 season, Manning does not appear to have played for the team until 1939. He apparently was sent to play for the Ponce team in the Puerto Rican winter league to get some seasoning, but no statistics are available for Manning’s time there.13

The next year Manning was ready to start his pro career in earnest, and he recalled his first start for Newark in 1939 as the most memorable game of his career. After training in Miami, the Eagles barnstormed their way north to their New Jersey home. In Winston-Salem, North Carolina, they played a game against the defending NNL champion Homestead Grays. Manning said of his starting assignment, “You know they’re going to give me a baptism of fire here, but the thing about it is that I struck out the first five guys and that included anybody that was up there — Josh and Buck and everybody.”14 Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard are now in the Hall of Fame and the Homestead Grays won nine NNL pennants in 11 seasons from 1938 through 1948, so Manning knew after this start that he could compete with the best players in the league.

Manager Dick Lundy piloted a Newark team that included five future Hall of Famers: Mule Suttles, Willie Wells, Raleigh “Biz” Mackey, Leon Day, and Irvin. In spite of all their talent, the Eagles finished in second place, two games behind the Grays, with a league record of 32-21-1; their overall record was 37-21-1. Later in life, Manning said, “I don’t know why we didn’t do better than we did. … in ’39 we had a hell of a good team,” and he asserted that this team was even better than the Eagles’ 1946 squad that won both the NNL pennant and Negro League World Series.15 As for Manning, statistics show that he received limited playing time during his first full season and finished with a 1-4 record, 22 strikeouts, and a 5.80 ERA in 35⅔ innings pitched over seven games.

Although the Eagles fared worse as a team in 1940, Manning made progress toward becoming a star. He was the team’s co-leader in wins, along with Jimmy Hill, and finished 9-4 with a team-leading 66 strikeouts and a 4.38 ERA in 98⅔ innings. Newark finished with a 26-21-1 record in the NNL, only good enough for third place. Mackey replaced Lundy toward the end of the season and led the team to a 5-2 record during his brief tenure as manager. Several sources show that Manning spent the winter league season in the Dominican Republic after the NNL season although, again, no statistics for his time in that country are available.16

On the heels of his success in 1940, Manning ran afoul of Effa Manley — Abe’s wife and the Eagles’ co-owner who negotiated all salaries — when he held out for more money at the beginning of the 1941 season. Like most owners, Manley tried to sign her team’s players for as little money as possible, and she often acted as though she had been betrayed when a player held out. Of his relationship with Effa Manley, Manning said, “She never cared too much for me as a person. We were both stubborn, [which] didn’t help the situation.”17

Manning deemed Manley’s salary offer to be unsatisfactory and returned his unsigned contract to her. He included a letter with the contract in which he wrote, “A Negro baseball player’s life is a hard one. He has to make money while he is still young and spend it wisely. Likewise he must obtain his salary however and where ever he can.”18 The “where ever” was an implied reference to the fact that Mexican League President Jorge Pasquel was luring away many Negro League players with higher salaries. Manley apparently got the hint as she acquiesced to Manning’s salary demands.

Once the 1941 season commenced, Manning and the Eagles picked up where they had left off the previous season. In an instance of déjà vu, the team — this time under Mackey’s guidance for the entire year — finished in third place with a 27-23-1 record in NNL play while Manning and Hill tied for the team lead in wins. The win total had fallen off to six for both pitchers, however, and Manning’s final statistics show a 6-5 record, 50 strikeouts, and a 4.36 ERA in 109⅓ innings pitched.

In 1942 Manning may have thought that he was stuck in a time loop as Newark again finished in third place and he tied for the team lead in victories once more with seven (although Leon Day was the co-leader this year). The 1942 incarnation of the Eagles had six future Hall of Famers — Suttles, Wells, Day, Irvin, Ray Dandridge, and Larry Doby — but finished with a losing record of 28-30-3 in NNL play, although their overall record was 36-33-3. Mackey had departed, thus depriving the team of a seventh Hall of Famer, and Wells took over the managerial reins for the season. Manning showed vast improvement as he shaved more than 1½ runs off his ERA, lowering it from 4.36 in 1941 to 2.63 in 1942. He finished the campaign with a 7-5 record and 52 strikeouts in 99⅓ innings pitched. The 1942 Eagles team was another squad that Manning thought was better than the 1946 championship team; however, as had been the case with the 1939 Eagles, they did not achieve spectacular results.19

Manning’s baseball career was put on hold when he was drafted and inducted into the US Army on September 1, 1942. He served for the duration of World War II plus another five months afterward, which caused him to miss the 1943 through 1945 seasons. He went through basic training in Fort Dix, New Jersey, and then was assigned to the Quartermaster Corps, serving with the 316th Air Squadron at Richland Airfield in Virginia. Unlike many baseball players, both black and white, Manning did not get to play on a baseball team at any point during his service. He did not completely forgo sports activities, though. In February 1944 it was reported that “Sergeant Max Manning, Newark, N.J., former pitcher of the Newark Eagles, professional baseball team, is now coach of the Owls basketball team of the 316th Aviation Squadron. …”20

Manning did not coach basketball much longer because he was sent to France, where he arrived on July 6, 1944.21 He became a truck driver on what was called the Red Ball Express, “hauling supplies to the frontlines for the Third Army.”22 After Germany surrendered, Manning was sent briefly to the Philippines and then to Japan.23 In January 1946 he was sent back to Fort Dix, where he was discharged.

Manning was elated to be playing baseball again when the 1946 season began. He explained, “Being in the service and not playing ball for three years does something to you. It has an effect on you. After getting home again, spring training was almost like therapy. There was a feeling of comfort and it let you kind of get back on track.”24 Manning was not the only military veteran who returned to the Eagles in time for the 1946 season. The press reported that Biz Mackey, who was back with Newark once more, “has whipped a host of ex-GIs into shape for the coming race and feels certain that the Newark club will be in the thick of the pennant battle.”25 In addition to Manning, the list of Newark’s ex-GIs included Day, Doby, Irvin, Oscar Givens, Clarence “Pint” Isreal, Charles Parks, and Leon Ruffin. Playing with renewed vigor after their wartime experiences, they helped to take the Eagles to previously unattained heights.

The season began with a bang as Day pitched an Opening Day no-hitter on May 5 against the Philadelphia Stars. Manning recalled losing his first start but recovering quickly, saying, “Oh, Lord, it’s going to be a bad season for me. That damn army … and so on. Then I won 15 straight.”26 Mackey — with his fellow future Hall of Famers Day, Doby, and Irvin back in the fold — led the Eagles on a season-long tear through the NNL. Newark finished 50-20-2 in league play, and 56-24-3 against all competition, as the team won both the first- and second-half NNL titles. Manning was the winning pitcher on September 4 as the Eagles clinched the second-half title with a 17-5 annihilation of the New York Cubans at Newark’s Ruppert Stadium. Newark scored nine runs in the first inning, Doby rapped out five consecutive hits in the game, and Manning supported his own cause with a home run in the eighth inning.27 In light of the Eagles’ dominance all year, it was a fitting way to clinch a trip to that year’s Negro League World Series in which they faced the NAL’s Kansas City Monarchs.

Kansas City had posted a 43-14 record in NAL play and, like Newark, had won its league’s pennant without a playoff series. The Monarchs had their own stable full of future Hall of Famers, including outfielder Willard Brown, pitcher Hilton Smith, and the immortal Satchel Paige. Thus, the World Series ended up being a tight affair that required the full seven games to determine which team would be the champion of the Negro Leagues in 1946.

The Monarchs prevailed, 2-1, in Game One at New York’s Polo Grounds on September 17. Two days later, boxer Joe Louis threw out the first pitch prior to Game Two in which Manning took the mound at Ruppert Stadium and pitched a complete game, striking out eight, as Newark evened the series with a 7-4 victory. The teams split the next two games before Manning made his second start in Game Five at Comiskey Park in Chicago. Manning again went the distance and struck out seven Monarchs batters, but he lost a 5-1 decision as the Monarchs took a three-games-to-two lead in the series. The Eagles then came back to win Games Six and Seven, 9-7 and 3-2, at Ruppert Stadium to claim the title.28

World Series Game Seven was played on September 29 and Manning joined a new team the very next day. On the heels of his outstanding 1946 season, Paige had selected Manning as one of the pitchers for his Satchel Paige’s All-Stars team that barnstormed across the United States against major-leaguer Bob Feller’s All-Stars from September 30 to October 26. In one game at Dayton, Ohio, Manning struck out 14 major-league hitters but took a tough 2-1 loss when he surrendered a homer in the ninth inning.29

Manning followed up his stint with Paige’s All-Stars by traveling to Cuba to play for the Cienfuegos Elefantes. His initial foray into Cuba was not as successful as his season with the Eagles had been as he posted a 4-8 record with 29 strikeouts in 86⅓ innings pitched.30 Cienfuegos finished the season at 25-41, which put them in a third-place tie with Marianao, 17 games behind first-place Almendares.

The lack of overall success in Cuba during the 1946-47 winter season did not mean that there were no highlights for Manning. On December 22 he outdueled St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Max Lanier, who was making his first start for Almendares, by a 1-0 score. Manning earned the win when player-manager Martin Dihigo — another future Hall of Famer — hit a game-winning ninth-inning single. It was “the last hit Dihigo recorded on a Cuban ballfield.”31

On January 23, 1947, Manning shut out Marianao, 10-0. The game was reminiscent of Newark’s second-half pennant clincher against the New York Cubans as Cienfuegos likewise scored nine runs in the first inning, allowing Manning to cruise through the game.32 A month later, on February 18, Manning found himself in another pitchers’ duel, this time against Cuban legend Agapito Mayor and the Almendares club. By all accounts, “Manning pitched superbly for Dihigo, giving up only two runs, but Almendares was hot and Mayor unbeatable.”33 The game ended as a 2-0 whitewash by Mayor.

Later in life, Manning rightfully summed up his 1946 season, saying that it “was probably my best year in baseball, in terms of things that I did and accomplishments that I managed to do.”34 From Newark to Paige’s All-Stars and on to Cuba, Manning observed, “Everything happened that year” and laughingly asserted, “It was a good money year.”35

When the 1947 season rolled around, Manning decided that he wanted to have a “good money year” with Newark as well and, for the second time, held out for higher pay. Once again, he sent his unsigned contract back to Effa Manley along with his salary demand. Manning was still holding out as spring training began, so Manley again acquiesced. As Manning recollected, “Finally, we made an agreement for $600 a month, almost double what I was getting before.”36

Since Manning signed in time for the season’s start, he was on hand for Opening Day at Ruppert Stadium on May 11. Prior to the game, the NNL president, Rev. John H. Johnson, presented watches to Irvin for winning the 1946 batting title and to Manning for having the best pitching record. Manning picked up where he had left off and began to earn his higher salary by pitching a five-hitter as Newark defeated the Philadelphia Stars, 10-2, in the first game of a doubleheader. Lennie Pearson and Doby both homered in support of Manning.37 Doby soon was sold to the Cleveland Indians and integrated the American League that season. The Eagles also captured the nightcap, 4-0, and were off and running again.

The highlight of Manning’s year — and no doubt a major reason that he desired higher pay — took place off the field: it was his marriage to Dorothy Winder, the daughter of James and Lucy (Boyd) Winder of Pleasantville, New Jersey. Manning told the story of how he won over his bride:

I met her father first, he was a postman. … I was always over at his house and Dorothy was always in the kitchen cleaning up. … I went into the kitchen to talk to her. She didn’t like me, but after 2 or 3 times I convinced her to go with me to a movie. We dated, her parents approved, and we were married in 1947.38

The couple remained married for 55 years, until Dorothy’s death on December 29, 2002. They had four children, Max Jr., Belinda, Boyd Martin, and Joan.

On the field, Manning was earning every penny as he compiled a 12-5 record with 80 strikeouts and a 2.99 ERA in 132⅓ innings. He was impossible to overlook anymore and was selected to participate in his first East-West All-Star game. Two East-West games were played in 1947, but Manning played in only the first one, the annual showcase game at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. In addition to 48,112 fans, several major-league scouts were present at the game on July 27. Unfortunately for Manning, who started the game for the East, this was one of his worst outings as he “gave up five hits in (2⅔) innings which were productive for the West in the sum of four runs which were enough to win the game.”39

As for the Eagles, with Manning’s 12 wins leading the staff, they finished 50-38-1 in the NNL, which left them in second place, six games behind the New York Cubans. Although there was no World Series for Manning this season, he did receive a compelling offer from the Cubans’ owner, Alex Pompez, who was helping white teams to procure Negro League talent now that Jackie Robinson and Doby had begun the integration of the major leagues.40

Pompez asked Manning if he would like to play for the New York Giants. Manning recalled that, in the spring, “I had just had a big-time argument with (Effa Manley) about salary and I held out.”41 Although Manning and Effa Manley never got along well, he was an honorable man and — especially since Manley had granted his salary request and he was still under contract — he said that Pompez needed to negotiate with Manley. Pompez was taken aback and refused to do so. When Pompez asked Manning whether or not he wanted to play in the major leagues, Manning responded, “More than you could ever know, but if you don’t have honor, what do you have?”42 While most Negro League players freely jumped from one team to another and had no qualms about leaving the Negro Leagues for Organized Baseball, Manning was more than content to forgo his best opportunity to make the major leagues in order to keep his integrity intact.

With his conscience clear, Manning returned to Cienfuegos, Cuba, for the 1947-48 winter league season. While his team finished in third place again with a 35-37 record, Manning’s second go-around in Cuba was much more successful individually. With a 10-8 record, he led the pitching staff in wins and had 69 strikeouts and a 3.13 ERA in 172⅓ innings.43

Manning attributed some of his success to a new pitch he learned from Carl Erskine, the soon-to-be Brooklyn Dodgers star. Manning always had trouble with one particular batter whom Erskine retired easily, so he asked, “What do you throw this guy to get him out? He told me it was a straight change and he showed me how to throw it. I picked it up real quick and I began to use it right away.” Manning used his entire repertoire to great effect as he outdueled fellow Negro Leaguer Dave Barnhill of Marianao, 1-0 on October 24 and posted another shutout in a 2-0 triumph over Almendares on February 7.44 Many players competed year-around, but all of this work soon contributed to the decline of Manning’s career.

Manning admitted to being overconfident that he was already in shape during spring training in 1948 because he had played winter-league ball. Manager Biz Mackey wanted to bring Manning along slowly, but when Len Hooker was knocked out of a start after only one inning, Manning pitched the remainder of the game. He later confessed, “And I wasn’t in condition and something went wrong.”45 Manning had a consultation with Dr. John Moore at Temple University Hospital who diagnosed a shoulder separation and told him there was nothing he could do other than to lift weights to try to thicken his muscles.46 Weightlifting did not help much, so Manning had to alter his pitching style completely. As he put it, “I learned how to spot pitch — throw slow, slower, and then slower — and I managed to win ballgames.”47

For the time being, the “new” Manning pitched as well as, or better than, the previous power pitcher had. He finished the season with a 10-4 record, 75 strikeouts, and a sparkling 1.62 ERA in 116⅓ innings pitched. His performance was rewarded with another selection to the East All-Star team. This time, Manning started the second East-West game, which was played before 17,928 fans at Yankee Stadium on August 24. He pitched three solid innings, allowing only one run and striking out two batters, as the East team claimed a 6-1 victory.48

Newark finished 29-28-1 in the NNL, which was only good enough for third place. The Homestead Grays won the last NNL pennant and the last Negro League World Series as the NNL disbanded at the end of the year. The continued influx of black players into the minor and major leagues had led to a dramatic decline in attendance at Negro League games that caused extreme financial hardships for team owners. Rather than simply disband the Eagles team, the Manleys sold the franchise to Dr. W.H. Young — a native Texan who had become a prominent Memphis dentist — and his business partner, Hugh Cherry. Young decided that they would move the team to Houston, Texas, for the 1949 season.

Manning looked back fondly on his time with the Manley-owned Eagles in Newark. He had developed a great relationship with Abe Manley, whom he and all the players called Cap [short for Captain]. Manning declared, “I had a lot of feeling for him. … And he responded, too. He’d tell me things more than the other guys. … His riding with the team [and] participating in the male companionship were the big part of getting to know him.”49 As for Effa Manley, Manning conceded, “Regardless of how you felt about her, you had to admire her abilities, what she was able to do. … As I look back, I appreciate her more and more.”50 All of baseball eventually came to appreciate Effa Manley and, in 2006 she became the first — and as of 2019 the only — woman to be inducted into the Hall of Fame.

As the NNL was coming apart and the Eagles were being sold, Manning continued to pitch for Cienfuegos in the winter. In spite of the success he had managed to have with Newark, the toll that his shoulder injury was taking on him now began to show. He struggled to a 5-12 record and had a 4.24 ERA in 129⅓ innings; most tellingly, he struck out only 42 batters while walking 73 and his 12 losses were the most in the Cuban League that season.51 One of his losses was a tough 1-0 game against Havana on December 5. Former Eagles teammate Rufus Lewis pitched a four-hitter for Havana while Lennie Pearson scored the winning run on a fly ball in the eighth inning.52

As spring training approached in 1949, Manning again held out for more money. Since he knew that his arm would not last much longer, it is likely that he wanted to maximize whatever earnings he had left in baseball. Although much of the Eagles’ roster remained the same, some stars — most notably Leon Day and Ray Dandridge — had no interest in playing their home games in Texas and did not sign with the team. Young, the new owner, had hoped that the team would become financially viable again in Houston, which had an African-American population of over 80,000.53 The Eagles were now part of the NAL’s Western Division and played their home games at Buffalo Stadium — the home of the Texas League’s Houston Buffaloes — when it was available. In order to keep expenses down, the NAL decided to play games only on weekends, and the Eagles played only at night in the hope that more fans would be able to attend.54

Nothing worked. The Houston fans had no idea who the Eagles players were — other than local hero Andrew “Pat” Patterson — and thus developed no rooting interest in the team. A spring-training article had reported, “Manager Ruben Jones … stated that the Eagles will be one of the teams to beat for the championship,” but that turned out not to be the case as the team finished in last place in both halves of the season.55 The team was so wretched that Jones resigned after the first half, “citing old age,” and was replaced by Red Parnell.56 No doubt the Eagles’ performance had aged Jones considerably in just a few months.

Manning did everything he could do, sore shoulder and all, once he joined the team in late May. In early August it was reported that he had a 5-2 record while second baseman Johnny Washington was among the NAL leaders with a .366 batting average; they were the lone bright spots on the team.57 On August 11 he defeated the Monarchs, 7-4, in Omaha, Nebraska, retiring 16 consecutive batters at one point.58 In perhaps his best performance of the season, he defeated the NAL Eastern Division’s first-half champions, the Baltimore Elite Giants, by a 5-1 score at Baltimore’s Bugle Field; his mound opponent that day was future Brooklyn Dodger Joe Black.59 Complete statistics for the 1949 season are unavailable, but it is clear that Manning managed to thrive where others did not.

As his career started to wind down, Manning spent one last winter in Cuba, though he now played for the Havana Leones. His pitching line was better than in the previous year as he finished 8-5 with a 3.38 ERA in 130⅔ innings; however, he still struggled with control as a spot pitcher as was evidenced by the fact that his walks again outpaced his strikeouts, 53 to 27. Although he was with a different team, it finished in a familiar place — tied for third with Marianao, three games behind first-place Almendares.60

Manning had even fonder memories of the winters he spent in Cuba than he did of his seasons in Newark. The primary reason for his love of Cuba and other Latin American countries was the same as it was for most black players, namely that they were treated far better there than in their home country. Manning emphatically declared:

I’m saying in terms of being somebody, when you went to Latin America, you were somebody and you were treated as somebody and the newspapers treated you as somebody, and the people treated you as somebody. You had the best accommodations of all. … It was just a marvelous experience and everywhere I went in Latin America it was the same thing.61

All of these circumstances stood in stark contrast to the racism and segregation that black players encountered in the United States.

When Manning returned from Cuba, he did not re-sign with the Houston Eagles for the 1950 season. Instead he pitched for Maracaibo in Venezuela’s summer league. Manning said he was paid $1,000 per month plus expenses and that ex-Eagles Johnny Davis and Len Hooker played on the Maracaibo team as well.62 The Maracaibo-based summer league did not receive the same level of fan support or press coverage as Venezuela’s Caracas-based winter league and no statistics from the 1950 season are available. One certainty is that Manning’s shoulder injury was getting worse. He said, “I remember going back to the hotel in Maracaibo after the game, putting hot towels, alcohol, wintergreen on my arm, trying to think what else I can use.”63

In 1951 Manning became something of a baseball vagabond. He began the season with the Mexican League’s Jalisco Charros, with whom he had limited success. In April he earned his first victory in Mexico, a 5-3 decision against Nuevo Laredo that completed a three-game series sweep.64 Then, in late May, he defeated Torreon, 3-2, shortly before he left Mexico.65 Manning finished his brief stint with Jalisco with a 2-4 record, 23 strikeouts and a 3.02 ERA in 59⅔ innings pitched.66

Manning’s reason for leaving Jalisco in midseason was that he had one last shot at the major leagues, though he knew that his shoulder was too far gone for him to make it. The Philadelphia Athletics had offered him a tryout “by virtue of contact through Claude Larned, a scout in the St. Louis Cardinals organization.”67 The A’s liked Manning, but all he ended up doing for the team was participating in exercises to try to get into better shape.

While he was in limbo in the Philadelphia Athletics organization, Manning’s wife called to inform him of an offer to play in Canada. The Sherbrooke Athletics of the Class-C Quebec Provincial League offered Manning a two-month salary advance of $1,200 to play for them.68 Manning honored his two-month commitment to Sherbrooke and then joined the Brantford Red Sox of Canada’s Inter County League for the remainder of the season.69 He continued to pitch in spite of the fact that he experienced constant shoulder pain. Just as he had resorted to various remedies while in Venezuela, Manning said of his time in Canada, “I can remember sitting on the bench up there in Sherbrooke and at that time they didn’t have Tylenol and Excedrin and all these pain relievers. The only thing they had at that time was aspirin. I remember sitting on that bench, inning after inning, popping aspirin, trying to reduce the pain.”70 Manning confessed that he put himself through such agony because “I didn’t know how to do anything else but play ball.”71

Manning soon sought to remedy that fact that all he knew was baseball. Once he returned home at the end of the 1951 season, he enrolled in the New Jersey State Teachers College at Glassboro with an eye toward finally finishing the studies that he had begun at Lincoln University 14 years earlier. Baseball was still in his blood, however, and he continued to pitch occasionally during the next few summers.

In August of 1952, Manning was in the Dominican Republic and ended up taking part in a game that devolved into chaos. The Sporting News reported that Luis Olmo, who had played for the Brooklyn Dodgers and Boston Braves, took umbrage when Cuban pitcher Wilfredo Salas sailed a pitch too close to his head. Olmo’s reaction stemmed from the fact that a Salas beanball had put him in a hospital for a month when both players were in the Mexican League. On this occasion, Olmo went after Salas with a bat. According to the game report, “Marines, policemen, umpires, and players from both teams swarmed onto the diamond. When peace was restored, Olmo was hustled off to the local bastile [sic] by the gendarmes.”72 The game resumed and when Salas came to bat, he homered, “the wallop coming off the North American pitcher, Max Manning” who “eventually lost 8 to 1.”73 There are no further accounts of Manning in action in the Caribbean in 1952, and it is doubtful that he was there for long.

In similar fashion, Manning returned to Mexico in the summer of 1953 to play for Torreon. Whether he was simply trying to earn extra income in the summer the easiest way he knew how, or simply could not get baseball out of his system yet, Manning endured the shoulder pain and pitched on. In his limited time with Torreon he went 3-5 with 49 strikeouts and a 4.27 ERA in 71⅔ innings.74 Manning related that his wife had tired of his baseball travels and wanted him to finish his education before the GI Bill of Rights benefits he had earned were set to expire. She may have been worried that her husband would succumb to the baseball bug full-time again before finishing his degree. Manning explained, “My wife wrote me and said, ‘Look, fella, I don’t want you to be a baseball bum.’”75 Her missive had its intended effect as Manning told Torreon’s management “I gotta go” and returned stateside to complete his education.76

Perhaps because Canada was a lot closer to home than Mexico, Manning did have one last stint with Brantford in the summer of 1954. He helped the Red Sox during the Inter County League’s pennant race and on August 13 pitched a four-hit shutout against the Guelph-Waterloo Royals in the first game of a doubleheader; the Red Sox also won the nightcap and moved into first place.77

After this final hurrah, Manning finished his studies and graduated from Glassboro in the spring of 1955. During his time at the institution, he had played on the school’s baseball and basketball teams — his professional baseball activities did not make him ineligible at that time — and he was inducted into the school’s athletic Hall of Fame in 1986. The institution, now named Rowan University, noted that Manning “played for the baseball team from 1952-55, starting as a 33-year old freshman” while acknowledging that he “was a pitcher for the Newark Eagles in the Negro Leagues.”78 Given Manning’s “Profesor” nickname, it was perfectly fitting that Glassboro’s athletic teams were named the Profs.

After earning his degree, Manning taught sixth grade for 28 years in his hometown of Pleasantville, New Jersey, before he finally retired in 1983. Although he no longer worked at his profession, Manning was by no means inactive in retirement. In fact, a recap of his activities shows that he may have been busier than ever:

Max Manning was a role model for children and a baseball mentor to many youngsters in the Pleasantville area. He became involved in civil rights activities and enjoyed gardening and writing sports stories.

He served as president of the Pop Lloyd Foundation in Atlantic City for many years and was instrumental in securing funds for the restoration of the stadium that was named after the famous Negro League player. Max Manning’s hometown renamed the Pleasantville Park Avenue recreation field in his honor.

A Max Manning scholarship was established by the Pop Lloyd Committee honoring his career in the Negro Leagues and his 28 years in education. … The award was designed to be granted to a student pursuing a career in education.79

On August 20, 1999, Manning received another honor during “Turn Back the Clock Night” at Atlantic City’s Sandcastle Stadium. A large sculpture that included 12 players was unveiled to commemorate the Negro Leagues. Among the 12, Manning saw “his image as he was about to uncork a fastball to an unfortunate batter.”80 In a similar gesture, a mural depicting six Newark Eagles players, including Manning, was painted on Newark’s Riverfront Stadium as a lasting tribute.81

Max Manning died on June 23, 2003, in Pleasantville after a lengthy illness. While many people call to mind the lanky, bespectacled Dr. Cyclops who starred for many years with the Newark Eagles, his daughter Belinda reminded everyone that there was much more to her father, saying, “I want him remembered as someone who had strength of character, not only in baseball but also in what he taught in the classroom and what he brought to the community.”82

Acknowledgment

Many thanks to James Overmyer for providing a transcription of the interview he conducted with Max Manning in 1990 while in the process of gathering research for his book, Queen of the Negro Leagues: Effa Manley and the Newark Eagles. It provided invaluable information for this article.

Source

Unless otherwise indicated, all Negro League player statistics and team records provided were taken from the Seamheads.com website. It should be noted that Negro League statistics often vary from source to source. Some variations are due to the fact that certain sources include both league and exhibition games, while other sources include only official league games in their tallies. Additionally, some sources do not include games for which only line scores — rather than full box scores — are available since appearances, starts, wins, and losses are the only statistics to be gleaned from them.

Notes

1 Brent Kelley, Voices From the Negro Leagues: Conversations With 52 Baseball Standouts (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1998), 67.

2 James Overmyer, interview with Max Manning, August 23, 1990, Pleasantville, New Jersey.

3 Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003), 391.

4 U.S. Colored Troops Military Service Records, 1863-1865, ancestry.com, accessed January 5, 2019.

5 C. Maxwell Manning, “Negroes and Liberia: Why They Return,” Columbus (Georgia) Ledger, September 6, 1903: 6.

6 Kelley, 68-69.

7 Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, Supplement: Lynchings by County, 2nd Edition, eji.org/sites/default/files/lynching-in-america-second-edition-supplement-by-county.pdf.

8 Joseph DeLuca, “Max Manning — South Jersey’s Pitching Ace,” 1991, from the Max Manning file, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

9 Kelley, 69.

10 Ibid.

11 Overmyer interview.

12 Kelley, 67.

13Overmyer Interview. Manning said that he started with the Eagles in 1938, which was the year that he signed with the Newark team; however, he did not pitch for them until the spring of 1939. Multiple sources list Manning with the Ponce team during the Puerto Rican winter league’s inaugural 1938-39 season, but no statistics are available; for one such source, see William F. McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2007), 215.

14 Kelley, 70.

15 Overmyer interview.

16 There is a lack of documentation about this stint in the Dominican Republic, and it is possible that Manning once again played for Ponce in Puerto Rico rather than in the D.R., especially since the Manleys were known to send Newark personnel to play in Puerto Rico in the winter. Ships’ passenger lists show only that Manning arrived in San Juan, Puerto Rico, on October 30, 1940, though he certainly could have traveled to the Dominican Republic from San Juan. All that can truly be ascertained at this time is that Manning did play winter-league ball again during this year.

17 Overmyer interview.

18 James Overmyer, Queen of the Negro Leagues: Effa Manley and the Newark Eagles (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1998), 94-95.

19 Overmyer interview.

20 “Baseball Star Coaching Army Basketball,” Los Angeles Tribune, February 14, 1944: 8.

21 DeLuca.

22 Brett Kiser, Baseball’s War Roster: A Biographical Dictionary of Major and Negro League Players Who Served, 1861 to the Present (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2012), 152.

23 DeLuca.

24 Monte Irvin with James A. Riley, Nice Guys Finish First: The Autobiography of Monte Irvin (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1996), 97.

25 “Newark Eagles to Meet Stars,” Wilmington (Delaware) Morning News, May 6, 1946: 15.

26 Kelley, 71. Manning may have won 15 games that year, although most sources list fewer wins. John B. Holway’s The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House Publishers, 2001), 436, credits Manning with 13 wins that season while Seamheads.com shows Manning with an 11-3 record, 78 strikeouts, and a 3.06 ERA in 126⅔ innings pitched. See Source note for the reason for such discrepancies.

27 “Eagles Win, Take Flag,” Newark Star-Ledger, September 5, 1946: 15.

28 The brief summaries of the World Series presented here were culled from Richard Puerzer’s comprehensive account of the Series that appears in the present volume and from Kyle McNary, Black Baseball: A History of African-Americans & the National Game (New York: Sterling Publishing Company, 2003), 120-24.

29 Alfred M. Martin and Alfred T. Martin, The Negro Leagues in New Jersey: A History (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2008), 53.

30 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003), 281.

31 Lou Hernández, The Rise of the Latin American Baseball Leagues, 1947-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2011), 96.

32 “Cubans Cheer Dolf and Mike in Battery Act Before Benefit,” The Sporting News, February 5, 1947: 10.

33 Roberto González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 37.

34 Kelley, 71.

35 Ibid.

36 Overmyer interview.

37 Bob Luke, The Most Famous Woman in Baseball: Effa Manley and the Negro Leagues (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 135.

38 DeLuca.

39 Dan Burley, “Confidentially Yours: East-West Classic Replay,” New York Amsterdam News, August 2, 1947: 10.

40 There are discrepancies among numerous sources as to whether this event occurred toward the end of the season in 1946, 1947, or 1948. The year 1946 is too soon for two reasons. The first is that even Jackie Robinson had not yet made it to the major leagues, so no offer to go directly to the Giants would have been forthcoming. The second reason is that Manning was not yet under contract for 1947; thus, if the offer had been made at that time, he would have felt no obligation to the Manleys and likely would have signed with the Giants. Manning’s allusion to his holdout in the spring of 1947 and the higher salary it brought him also shows why he felt such an obligation to honor his contract with the Eagles at that time and make it clear that Pompez’s offer came toward the end of the 1947 season. Additionally, the 1948 season is too late a date because the shoulder injury that Manning suffered early that year would have labeled him as “damaged goods” and it is unlikely that he would have received an offer to go to the majors at that point. According to DeLuca, when the Philadelphia Athletics contacted Manning in 1951, his integrity came to the fore again as he “tried to tell them that his arm was shot.” It is most likely that he would have told the Giants the same thing if they had contacted him at the end of 1948.

41 Kelley, 72.

42 Martin and Martin, 55.

43 Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961, 296.

44 Rene Canizares, “Player Battle May Force Cuban Loops Into Court,” The Sporting News, November 5, 1947: 19; Pedro Galiana, “Gonzalez’ Club in Spirited Bid for Cuban Flag,” The Sporting News, February 18, 1948: 20.

45 Kelley, 72.

46 Overmyer interview.

47 Kelley, 72.

48 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 321-22.

49 Overmyer interview.

50 Ibid.

51 Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961, 312.

52 Pedro Galiana, “Gonzalez’ Reds Creep Close to Almendares in Upsurge,” The Sporting News, December 15, 1948: 23.

53 Rob Fink, Playing in Shadows: Texas and Negro League Baseball (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2010), 112.

54 Ibid.

55 “Pilot Jones Drills New Eagle Nine,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 26, 1949: 29.

56 Fink, 115.

57 “A Pair With Houston: Eagles Meet Monarchs This Afternoon at Blues Stadium,” Kansas City Star, August 7, 1949: 98.

58 “Monarchs Lose, 7-4,” Omaha World-Herald, August 12, 1949: 29.

59 “Houston Eagles Trim Elite Giants by 5-1,” Baltimore Sun, August 17, 1949: 16.

60 Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961, 323, 329.

61 Kelley, 71.

62 Overmyer interview.

63 Ibid.

64 Jorge Alarcon, “Ramirez’ Nifty Pitching Helps Jalisco Climb,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1951: 22.

65 Jorge Alarcon, “Gonzalez’ Bat in Spotlight for San Luis,” The Sporting News, June 13, 1951: 34.

66 Pedro Treto Cisneros, The Mexican League: Comprehensive Player Statistics, 1937-2001 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002), 386.

67 DeLuca.

68 Ibid.

69 Barry Swanton and Jay-Dell Mah, Black Baseball Players in Canada: A Biographical Dictionary, 1881-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2009), 109.

70 Kelley, 72.

71 Ibid.

72 Alejandro Martinez, “Olmo Jugged in Dominican Diamond Row,” The Sporting News, August 4, 1952: 32.

73 Ibid.

74 Cisneros, 386.

75 Kelley, 72.

76 Ibid.

77 Jay-Dell Mah, “1954 Ontario Game Reports,” Western Canada Baseball, attheplate.com/wcbl/1954_90i.html, accessed January 8, 2019.

78 “Max Manning — Class of 1955 — Rowan University-Glassboro State College Hall of Fame,” rowanathletics.com/hof.aspx?hof=8&path=&kiosk=, accessed January, 9, 2019.

79 Martin and Martin, 55.

80 Martin and Martin, 154.

81 Martin and Martin, 177.

82 “Negro League Star Manning Dead at 84,” from the Max Manning file, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Full Name

Maxwell Cornelius Manning

Born

November 18, 1918 at Rome, GA (US)

Died

June 23, 2003 at Pleasantville, NJ (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.