Rupert Mills

Days after his graduation from college in June 1915, Rupert Mills was signed by the Newark Peppers of the Federal League. A Newark native and a locally renowned schoolboy athlete, Mills was deemed the potential fan magnet desperately sought by Peppers management. Unhappily, the new recruit proved unequal to the task, batting an anemic .201 and playing shaky first-base defense during a 41-game audition. The ensuing winter, the collapse of the Federal League and the dispersal of its players brought the major-league career of Rupert Mills to its end.

Days after his graduation from college in June 1915, Rupert Mills was signed by the Newark Peppers of the Federal League. A Newark native and a locally renowned schoolboy athlete, Mills was deemed the potential fan magnet desperately sought by Peppers management. Unhappily, the new recruit proved unequal to the task, batting an anemic .201 and playing shaky first-base defense during a 41-game audition. The ensuing winter, the collapse of the Federal League and the dispersal of its players brought the major-league career of Rupert Mills to its end.

If Mills is remembered at all by baseball enthusiasts today, it is for the comedy he staged with Peppers club President Pat Powers during the 1916 season. Unlike his teammates, Mills declined the $500 contract buyout offer tendered him by Powers. Mills had signed a guaranteed two-season contract with Peppers management and he expected to get paid the full $3,000 outstanding on that pact – whether or not the Federal League continued play. Wary of a courtroom battle with the astute, legally educated Mills, Powers countered with a demand for specific performance of contract terms. To collect, Mills would be obliged to report to deserted Harrison Park each morning, get into uniform, and put in an eight-hour baseball workout. Which, to Powers’ astonishment, is exactly what Mills began doing. Soon, word of the solitaire baseball being played by the Federal League’s lone remaining ballplayer reached the local press.

Tongue planted firmly in cheek, Mills regaled inquiring reporters with tales of how he pitched to himself (mostly curveballs); how he fielded the batted balls that he hit; how he hustled to call close plays on the basepaths (he was always safe); and how, as his own official scorer, he invariably ruled questionable plays a base hit. When the press first attended such a Mills performance, its featured actor declared that he had already played 12 games against himself, and won all of them. News reports of Mills’ antics were found highly entertaining by local readers, and soon he was receiving newsprint attention nationwide, much to Pat Powers’ chagrin. In mid-June, the club boss threw in the towel and settled the contract dispute on Mills’ terms.

While his tenure as a major-league ballplayer may have been brief and farcical, Rupert Mills was otherwise a man of considerable accomplishment. Prior to joining the Peppers, he had been a varsity letterman in four different sports at the University of Notre Dame. At the end of the 1917 season, he left professional baseball to serve as an artillery officer in France during World War I. Thereafter, he remained active as a captain in the New Jersey National Guard. Although a lawyer admitted to practice in the Garden State, he mostly earned his living as head of a Newark insurance agency. Mills was also the leader and namesake of an 800-member civic organization devoted to local children’s charities.

With a sterling resume and admirable personal qualities, to boot – Mills was affable, becomingly modest, and scrupulously honest – it was not long before Newark’s political establishment sought him out. A Republican, Mills was twice elected to the New Jersey State Assembly, and thereafter appointed undersheriff of Essex County. In 1929 Mills was unopposed in the Republican primary for the powerful post of Essex County sheriff, and was considered a shoo-in in the November general election. And a run for governor of New Jersey was widely reckoned to be in Mills’ future. But all such plans were undone one July afternoon. A boating accident on the waters of Lake Hopatcong in northern New Jersey brought the life of Rupert Mills to an abrupt end. The rising young star of the New Jersey Republican Party was dead at age 36.

Birth Through College Graduation

According to modern baseball reference works, Rupert Frank Mills was born in Newark on October 12, 1892.1 He was the only child born to driver-deliveryman Frank Kemp Mills and his wife, the former Mary Walters. The backgrounds of the infant’s parents were quite different. His father, Frank, was descended from local stock that dated to pre-Revolutionary War days, and Presbyterian. His mother, Mary, was the daughter of German and Irish immigrants and Catholic. The couple decided to baptize their son in his mother’s faith, and baby Rupert would remain devoutly Catholic his entire life.

Large for his age and athletically gifted, young Rupe Mills began attracting attention while still in grammar school. By the time he graduated from Newark’s Barringer High School, Mills was a locally famous four-sport star and the New Jersey high-jump champion. While adept at his other games, baseball was clearly Mills’ best sport, and upon graduation, he received “attractive” contract offers from the New York Giants, Pittsburgh Pirates, and Cleveland Naps.2 But Mills deferred entering the professional ranks, opting instead for a year of postgraduate study and sport, most likely at St. Benedict’s Prep in Newark.3 Then, reportedly acting on the advice of major-league standout (and Notre Dame alumnus) Cy Williams, Mills embarked upon college life in South Bend.

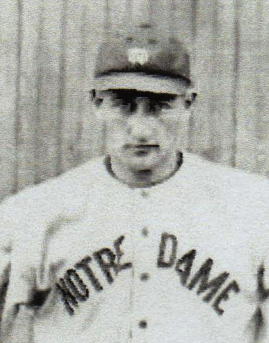

Arriving in September 1912, Mills quickly became a big-man-on-campus at Notre Dame. The by-now 6-foot-2, 185-pound newcomer was immediately installed at right end on the Notre Dame football squad. The following October, he was on the field when touchdown passes from quarterback Gus Dorais to left end Knute Rockne powered unheralded Notre Dame to a stunning 35-13 victory over mighty Army, revolutionizing college football and placing Notre Dame in America’s sporting consciousness in the process. In Mills’ three years as a two-way regular, Notre Dame posted a combined 20-2 (.909) record on the gridiron. Rupe enjoyed comparable success on the hardwood. In his three years as the basketball team’s starting center, the Notre Dame five went 38-10 (.792). He even managed to letter one spring for the track team, running sprints and throwing the javelin. Mills, however, was more than just a jock. He was diligent in the classroom and took active part in undergraduate social life, frequently appearing in campus theatricals4 and participating in other extracurricular activities. In addition, the well-liked Mills was elected president of the law student section by his classmates.5

While he was a stalwart on the Notre Dame football and basketball squads and often engaged in other aspects of campus life, where Rupe Mills really shined was the baseball diamond. His stint as a Notre Dame player, however, was almost derailed before it started. University officials were disturbed by reports that prospective first baseman Mills, as well as pitchers Bill Lathrop and Herb Kelly, had signed major-league contracts to take effect at the end of the 1913 college baseball season. Only affidavits signed by the trio denying such reports got them into an ND uniform.6 Once in harness, the righty throwing and batting Mills joined multi-sport star and future Cleveland Indians outfielder Alfred “Dutch” Bergman7 at the core of top-notch ND teams, batting a team-leading .394 during his junior season. In all, Notre Dame went 45-14 (.763) during Mills’ time as the university’s first baseman.

Notwithstanding the demands placed upon his schedule by the earning of some nine varsity sports letters,8 Mills completed his undergraduate course work in a timely manner.9 In June 1915, the University of Notre Dame therefore conferred a bachelor of laws degree upon him.10 But use of that degree would have to wait. Mills was now ready to answer the call of major-league baseball.

Rupert Mills’ Professional Baseball Career

During the years that Rupert Mills attended Notre Dame, a new professional baseball circuit burst upon the scene: the Federal League. After an inaugural season played as an independent minor league, the Feds declared themselves a major for the 1914 campaign. Unencumbered by the restraints on ballplayer acquisition placed on National and American League clubs by the National Agreement, the Feds disregarded reserve-clause holds on playing talent and immediately began raiding major-league rosters. Federal League willingness to pay handsome wages quickly drove player salaries higher, but with a few exceptions (like established stars Joe Tinker, Hal Chase, and a fading Three Finger Brown), the new league’s signees were mostly untested youngsters, journeymen, and past-their-prime veterans. The FL managed to complete the 1914 season intact, but several of its clubs, including the pennant-winning Indianapolis Hoosiers, were in serious financial difficulty by season’s end.11

Enter Harry Sinclair, a young oil tycoon looking to dabble in baseball club ownership. Under the tutelage of veteran baseball executive Patrick T. Powers, Sinclair made a bid for the Federal League’s Kansas City Packers franchise, only to be stymied by an injunction secured by the club’s incumbent owners. Sinclair had more luck acquiring the Indianapolis Hoosiers, but his efforts to relocate the franchise to New York for the 1915 season were thwarted by an inability to capture suitable ballpark grounds in Manhattan.12 The next best thing was nearby Newark, long the host city of top-tier minor-league clubs. Wiedenmayer’s Park, Newark’s established baseball stadium, was unavailable to Sinclair, tied up by the Newark Indians of the International League. But just across the Passaic River lay suitable ballpark grounds in the bustling little community of Harrison. And by Opening Day, a newly constructed 21,000-seat edifice called Harrison (or Peppers) Park was ready for Federal League play.13

Diminished by the departure of 1914 FL batting champ Benny Kauff and the relative ineffectiveness of returning 25-game winner Cy Falkenberg,14 the defending league champions struggled out of the gate. By mid-June, the Peppers were playing only .500 ball and stuck in mid-pack in the FL pennant chase. Home-game attendance, handicapped by the absence of a New Jerseyan on the playing roster and by the lack of convenient transport to the Harrison Park, was also a disappointment. For Peppers club President Pat Powers, the now-available Rupert Mills, a genuine prospect and a Newark native, might supply the antidote to such problems. Accordingly, Powers tendered a guaranteed two-year, $3,000-per-season contact to him. Although other major-league clubs, particularly the New York Giants, had retained interest in signing Mills, he was a homebody (who resided his entire adult life under his parents’ roof) and wanted to play locally. So, on June 22, 1915, Mills signed with Newark. He then immediately reported to Peppers manager Bill Phillips.15

Looking to add punch to the lineup, Phillips promptly inserted his large new first baseman into the action. Rupert Mills made his Federal League debut before home fans on June 23, 1915, going 1-for- 4 (a double) off Pittsburgh left-hander Frank Allen during an 11-1 drubbing administered by the Stogies. Palpably nervous, Mills also struck out twice and made three miscues at first base. But two days later, Rupe compiled probably the best box score of his brief major league career. His 2-for-3 off Kansas City right-hander Pete Henning included a seventh-inning bases loaded triple, the key blow in a 6-1 Newark victory over the Packers. Regrettably, Mills could not keep it up. After 14 games, his batting average had sunk to a meager .174 (8-for-46), with only six RBIs.

On July 6, new Peppers manager Bill McKechnie16 sent Mills to the bench, replacing him at first with converted catcher Emil Huhn. According to Sporting Life correspondent Edward B. Gearhart, Rupe had lost his confidence but would be “sent back into the game just as soon as he steadies down.”17 For the next seven weeks, however, Mills barely stirred, his three game appearances limited to pinch-hitting and pinch-running. But that September, McKechnie accorded Mills another shot, giving him 75 at-bats. The results, while an improvement, were something less than stellar: 17 base hits and 6 RBIs. But a 1-for-2 (with two walks) performance in Mills’ last game, on October 3, nudged his final season BA north of the .200 mark, if only barely. In 41 games total, Mills batted .201 (27-for-134), with little power (only six extra-base hits and 16 RBIs).18 Nor had his defensive play at first (a mediocre .976 fielding average with 10 errors) reminded anyone of Hal Chase. Still, Sporting Life’s Gearhart waxed optimistic at season’s end, informing readers that “Rupert Mills, now that he has recovered from his stage fright, has gladdened his many Newark friends by showing an improvement that is likely to make him a fixture at first base.” But larger forces were now in motion, and Mills would never play another major-league game.

As the financially distressed Federal League ambled toward dissolution, Mills spent the offseason learning the insurance business from Newark broker Joseph M. Byrne, the father of a former Mills teammate at Barringer High. He also read law at the offices of local attorneys with an eye toward taking the New Jersey bar examination at some future date. For the short term, however, Mills expected to make his living by playing baseball. But the Newark Peppers, like the other clubs of the FL, were a goner, with club owner Harry Sinclair peddling Newark player contracts to other major- and minor-league teams, usually at a handsome profit. Except in the case of Rupert Mills. Mills was not sought by other clubs, and he refused the $500 contract buyout offer tendered by club President Pat Powers. Mills had an ironclad contract that guaranteed him $3,000 for the 1916 season – whether the Federal League remained in existence or not – and he was not disposed to accept a penny less.19

Powers privately complained that Mills was being unreasonable, but he was not spoiling for a courtroom fight with the young lawyer-to-be. Rather, Powers would be beat Mills at his own legalistic game, demanding specific performance of contact terms accepted by Mills. To that end, Rupe would be obligated to report to deserted Harrison Park every morning, get into uniform, and put in an eight-hour baseball workout. But much to Powers’ surprise, Mills was agreeable. In fact, Mills would make a lark of his daily excursions to the ballpark, amusing himself by playing all kinds of imaginary one-man ballgames. In no time, word of the situation reached Newark sportswriters, who soon hastened to Harrison Park to take in the Mills show. Rupe was happy to oblige the scribes, supplying them with whimsical quotes that then found their way into newsprint. “I do mostly pitching in the morning to get me wise to my curves for the afternoon,” said Mills. “And when the umpire – that’s me, too – calls ‘Play,’ I just go out and bang the ball all over the lot.”20 He also advised that “Everything is a hit because Rupe Mills is official scorer [and] if I don’t lead the league in everything but errors it will be my own fault.” Still, as the game’s solitary player, it was “kinda hard to slam ’em out, beat the ball down to first base, and then have to call myself out (which he never did). The next thing I know I will be chasing myself to the clubhouse and Pat Powers is liable to fine me $10.” Running the bases also presented problems. “The other day I wrenched my ankle while sliding and had to put myself in to run for me,” Mills related. He then confided that “I have a devil of a time trying to pull a double steal.”21

When local news articles about Mills’ comic one-man ballgames began being republished nationwide, a frustrated and now somewhat embarrassed Pat Powers had had enough. Sometime in mid-June, he quietly called Mills into his office and settled their differences.22 The actual contract settlement terms were never publicly disclosed, but few observers doubted that the wily, strong-willed ballplayer had gotten his way. Although subsequent events are murky, it appears that Mills then signed a contract with the Detroit Tigers, who immediately optioned him to the Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Islanders of the Class B New York State League. Now facing pitchers other than himself, Mills batted a so-so .256 in 70 games for Harrisburg.23 That offseason, Detroit excised its option to recall Mills, only to farm him out once again, this time to the Denver Bears of the Class A Western League.24

Mills interrupted spring training with the Denver club for a trip home in March. Having passed the New Jersey bar exam some weeks earlier, he was admitted to the practice of law in the Garden State on March 19, 1917, the lawyer’s oath to uphold the Constitution being administered to him by New Jersey Chief Justice William Stryker Gummere, himself an old-time baseball player.25 Once back in Denver, Mills reestablished himself as a major-league prospect, batting a solid .285 and leading the Western League in games played (149), doubles (37), first-baseman assists (75), and fielding average (.987). But the possibility of a late-season call-up by Detroit was rendered moot by Rupe’s World War I-driven September enlistment in the US Army. As it turned out, heeding the call to military service brought the brief time of Rupert Mills in Organized Baseball to its end.

Military Service, New Jersey Politics, and an Untimely Death

Once he completed his basic military training, Mills was commissioned a first lieutenant and dispatched to an artillery division stationed in battle-ravaged France. In time, he saw action in and around Alsace and Verdun, and remained overseas with his unit well after the Great War’s end in November 1918. Mills was honorably discharged upon arrival home in Newark the following June, but then promptly enlisted in the New Jersey National Guard. Given the task of reorganizing the Guard’s 102nd Cavalry, he quickly whipped the troop into shape. Promoted to captain, Mills would remain unit commander until his death a decade later. To earn a living, attorney Mills represented the occasional client, but his principal endeavor was the insurance business. Putting into practice the skills learned from Joseph Byrne, Rupe opened his own agency, Rupert F. Mills & Company, with offices near his Newark home. Always community-minded, Mills also lent his name and assumed the leadership of the Rupert F. Mills Civic Association, a supporter of local children’s charities that soon grew to 800 members. And he remained a faithful congregant at St. Augustine Church, never missing Sunday Mass.26 For recreation, Mills played first base for the Meadowlarks, a fast Newark semipro nine.27 He also remained close to his alma mater, scouting East Coast high-school talent for his friend and former teammate Knute Rockne, now the Notre Dame athletic director as well as football coach. Rupe also hosted receptions for ND teams visiting the greater New York metropolitan area.

Military service, athletic renown, civic involvement, and a sterling personal character made Rupert Mills an attractive recruit for Newark’s political bosses, with the Republican Party, then the more progressive of New Jersey’s two major political parties, eventually securing Mills’ favor. In 1924, Republican Mills captured a Newark seat in the New Jersey State Assembly. He was reelected to a one-year term the following year. But thereafter, he was defeated in a bid for election to the Newark City Commission.28 The setback, however, was merely a temporary one. In contemplation of running him for higher office, party leaders installed Mills as undersheriff of Essex County, where he distinguished himself with competent and politically impartial discharge of his duties. In July 1929, Mills stood unopposed in the Republican primary for the post of Essex County sheriff, and was likely to face only token Democratic opposition in the November general election. Mills was therefore considered a sure shot for the locally powerful sheriff’s job, an excellent springboard for a future run for governor of New Jersey.

On Saturday, July 20, 1929, Mills drove to Lake Hopatcong, a rural retreat in North Jersey, for a private conclave of Republican Party officials. After strategizing about the coming elections, attendees repaired to the lake for some afternoon relaxation on the water. With some coaxing and provision of a life vest, Rupe persuaded his friend and former Assembly colleague Louis Freeman to get into a canoe with him. The two men had paddled a few hundred yards away from shore when calamity struck. Their canoe was upended by the wash of a passing speedboat and both men were pitched into the water. The situation presented no great peril to Mills, a strong swimmer. But nonswimmer Freeman was panic-stricken and cried out to his companion for help. Grabbing a paddle from the swamped canoe, Rupe thrust it toward the floundering Freeman. “Here, Louis. Grab the end of this and I’ll tow you in,” Mills instructed.

As the two slowly but steadily made their way to shore, a motor launch raced to their rescue. But as the boat neared, Mills suddenly released the paddle and turned around toward Freeman, his face contorted in a painful grimace. He then slipped below the surface. Rescuers soon hauled Freeman safely aboard the launch, but Mills was nowhere to be seen. Thirty agonizing minutes passed before his lifeless body was discovered under water a short distance from shore. Officially declared a drowning victim, the circumstances, plus the absence of water in his lungs, led most to conclude that Rupe had suffered a massive heart attack. The rising young star of the New Jersey Republican Party was dead at 36.29

Word of Mills’ death spread rapidly, stunning family, friends, and fellow Newarkers.30 Soon, tributes to his memory poured in, with leaders on both sides of the political aisle expressing their admiration of Rupert Mills and profound regret at his untimely passing. Frequent note was taken of the fact that Mills had lost his life heroically, trying to save that of a friend – a circumstance deemed emblematic of the courage and selflessness that had infused his character. An editorial in one local newspaper summed up his life thusly: “It is doubtful if the death of any other resident of Essex County would have brought to as many individuals a sense of personal bereavement as has that of Rupert F. Mills. His prowess as an athlete made him the idol of youth. His manly character endeared him to those of mature years. He was square, honest and clean. He helped many. He injured none. He leaves an untarnished memory.”31

Mills was buried in his National Guard uniform and with full military honors. Upward of 20,000 lined the few short blocks between the Mills residence and St. Augustine Church, their heads bowed in silence as the honor-guarded caisson bearing his casket passed by. Mills’ horse, Friendship, saddled but riderless, trailed behind. The 1,000 mourners who crammed the church for the Solemn Requiem Mass included New Jersey Governor Morgan Larson, members of the state’s congressional delegation, Col. H. Norman Schwartzkopf Sr., commandant of the New Jersey State Police, and dignitaries from both political parties.32 Interment at St. Mary Cemetery in nearby East Orange followed. Never married and without children, Rupert F. Mills was survived by his parents and more distant family members.

A Final Word

Although his major-league career was brief and undistinguished, a small sort of immortality is conferred on Rupert Mills by the fact that his name will forever be inscribed in baseball reference works. Sadly forgotten is the much larger life that he lived beyond the diamond. An able and devoted servant of his church, community, and country, Mills was an admirable man who accomplished considerable good during his shortened lifetime. And he would likely have done a great deal more had fate been kinder to him.

Acknowledgments

This biography was originally published in the SABR Deadball Era Committee newsletter, The Inside Game, Vol. XVIII, No. 3 (June 2018). This version was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

Sources for the biographical information recited herein include Mills family posts accessible via Ancestry, particularly a five-page Rupert Mills biography penned by descendant Robert Mills; certain of the Mills profiles identified in the endnotes, and the extensive reportage of Mills’ death and funeral published in the Newark daily newspapers of July 1929. Unless otherwise noted, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet.

Notes

1 See, e.g., Baseball-Reference, Retrosheet, and the Baseball Almanac. These works have adopted the Mills date of birth originally published in the 1951 first edition of The Official Encyclopedia of Baseball, by Hy Turkin and S.C. Thompson. Characteristically, no source for their Mills biographical data is provided by T&T, and no contemporaneously published date of birth for Mills was discovered by the writer. US and New Jersey census listings are incompatible, having Mills born anywhere between January 1892 and “about 1895.” NJ birth and christening records viewable online, however, are quite specific. Same state that Mills was born on February 15, 1892, and baptized at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Newark on April 18, 1892. These dates, in turn, are contradicted by Mills himself, who provided a January 15, 1893, birth date to World War I draft authorities. Adding to the confusion are Mills’ July 1929 newspaper obituaries, which list him as 35 at the time of his death, an age that does not yield a February 1892 through January 1893 birth date.

2 As reported in Sporting Life, July 3, 1915.

3 As may be inferred from reportage in the Newark Jewish Chronicle, July 26, 1929, and from the fact that Mills completed a four-year course of academic study at Notre Dame while spending less than three years on campus.

4 In addition to Mills, the cast of an April 1914 production of the play What’s Next? included his dorm roommate Ray Eichenlaub, an All-American at fullback. For a photo of Mills and Eichenlaub in rather outlandish costume, see “Rupert Mills,” Notre Dame Archives: News & Notes, posted online July 20, 2013.

5 As noted in the 1915 Notre Dame yearbook, The Dome, 66.

6 As reported in the Canton (Ohio) Repository, May 8, 1913, and Bridgeport (Connecticut) Evening Farmer and Evansville (Indiana) Courier, May 9, 1913.

7 A year ahead of teammate Mills at Notre Dame, Bergman became the first of the four four-sport lettermen in university history. Mills was the next. The other two were Heisman Trophy winner Johnny Lujack and future NFL quarterback George Ratterman (whose fourth sport was tennis rather than track). Both Lujack and Ratterman attended Notre Dame in the mid-1940s.

8 According to a Mills descendent, Rupe earned three varsity monograms in baseball, three in basketball, two (not three) in football, and one in track. See Robert Mills, “Rupert Mills,” posted on Ancestry, July 2, 2011.

9 Mills was on campus in South Bend only from September 1912 to June 1915, but still managed to complete his degree requirements during that abbreviated span.

10 The undergraduate bachelor of laws degree earned by Mills is not to be confused with the post-college Juris Doctor degree conferred on law-school graduates.

11 For complete histories of the Federal League, see Daniel R. Levitt, The Battle That Forged Modern Baseball: The Federal League Challenge and Its Legacy (Lanham, Maryland: Ivan R. Dee, 2012), and Robert Peyton Wiggins, The Federal League of Base Ball Clubs: The History of an Outlaw Major League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing Co., Inc., 2010), both winners of the Larry Ritter Award. See also, Marc Okkonen, The Federal League of 1914-1915: Baseball’s Third Major League (Garrett Park, Maryland: SABR, 1989).

12 Like others before him, Sinclair had underestimated the power and resolve of New York Giants club president Harry Hempstead, whose surrogates quietly encumbered Manhattan real property eyed by Sinclair for a ballpark.

13 For an excellent overview of the club’s history, see Irwin Chusid, “The Short, Happy Life of the Newark Peppers,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 20 (1991), 44-45.

14 Falkenberg fell off to 9-11 before being sent to the FL Brooklyn Tip-Tops.

15 As reported in the Jersey (Jersey City) Journal, June 22, 1915, Springfield (Massachusetts) Union, June 23, 1915, and Sporting Life, July 3, 1915.

16 With the Peppers log standing at 26-27 on June 18, Phillips had been fired. Replacement McKechnie was the club’s regular third baseman.

17 Edward B. Gearhart, “Federal League Facts,” Sporting Life, July 17, 1915.

18 The Mills slash line was a dismal .201/.241/.254.

19 As explained in the Indiana (Pennsylvania) Evening Gazette, April 22, 1916, and Sporting Life, May 27, 1916. See also, Al Kermisch, “Researcher’s Notebook Unravels More Mysteries: Mills Kept Federal Loop Alive in ’16,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 15 (1986).

20 As per Cappy Gagnon, Notre Dame Baseball Greats: From Anson to Yaz (Charleston, South Carolina: Acadia Publishing, 2009), 73.

21 As per quotes originally published in the Newark Evening News and synopsized in “Rupert Mills: The One-Man Team of the 1916 Federalist League,” posted online at afftold.com, August 19, 2015.

22 It has been estimated that Mills made some 65 solo appearances at Harrison Park before his differences with Pat Powers were settled. See Kermisch, 3-4.

23 Per Cappy Gagnon, “Rupert Frank Mills,” SABR Biographical Research Committee Report, December 1999. Baseball-Reference provides no info for Rupert Mills in 1916.

24 According to bulletins by minor-leagues overseer John H. Farrell published in Sporting Life, September 16 and November 14, 1916. See also, Frank L. Weber, “Doings in Denver,” Sporting Life, March 17, 1917.

25 As reported in Sporting Life, March 24, 1917. Back in 1869, Gummere had also been the captain of the Princeton University team that faced Rutgers in the first recognized intercollegiate football game.

26 Following his death, detailed biographies of Mills were published in the Newark newspapers. Much of the above comes from the Newark Sunday Call, July 21, 1929.

27 Throughout his WWI service and beyond, Mills remained on the Detroit Tigers reserve list, but suspended. In early 1920, Tigers boss Frank Navin, finally convinced that Mills had no intention of returning to Organized Baseball, granted him his unconditional release, as reported in the New York Times, March 20, 1920. Mills played with the Meadowlarks through the 1923 season.

28 According to his obituaries, Mills’ relative youth and circumstances that peculiarly favored Newark Democrats that election year had worked against him.

29 Details of the Lake Hopatcong incident have been culled from reportage of the Newark Evening News, Newark Star-Eagle, and Newark Sunday Call, July 21 to 28, 1929. The writer is indebted to librarian Beth Zak-Cohen of the Newark Public Library for locating and providing copies of microfilmed newsprint.

30 News of Rupe’s death was privately conveyed to his devastated parents by Father George Buttner, the rector of St. Augustine Church.

31 “Rupert F. Mills,” Newark Sunday Call, July 28, 1929.

32 Knute Rockne was unable to attend the funeral, but cabled his condolences, telling Frank and Mary Mills that their son “was one of the finest men God ever made.” Newark Evening News, July 24, 1929.

Full Name

Rupert Frank Mills

Born

October 12, 1892 at Newark, NJ (USA)

Died

July 20, 1929 at Lake Hopatcong, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.