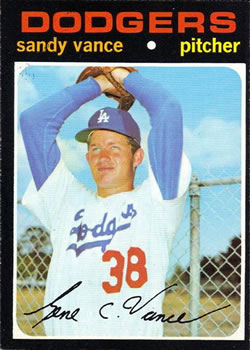

Sandy Vance

In the spring of 1970, a rangy 23-year-old right-hander stood atop the Los Angeles Dodgers’ minor-league pitching hierarchy. Sandy Vance, with a perfect name for Dodger fans to savor harkening back to Hall of Famers Dazzy Vance and Sandy Koufax,1 burst into the majors by happenstance that April, had solid seasons with both Los Angeles and Spokane, the organization’s top farm club, and then made the Dodger starting rotation for 1971. But he faltered early that season and just two years later, plagued by a “suspect fastball”2 and struggling in Class A, the former top prospect was released. Cumulative arm wear had taken its toll.3

In the spring of 1970, a rangy 23-year-old right-hander stood atop the Los Angeles Dodgers’ minor-league pitching hierarchy. Sandy Vance, with a perfect name for Dodger fans to savor harkening back to Hall of Famers Dazzy Vance and Sandy Koufax,1 burst into the majors by happenstance that April, had solid seasons with both Los Angeles and Spokane, the organization’s top farm club, and then made the Dodger starting rotation for 1971. But he faltered early that season and just two years later, plagued by a “suspect fastball”2 and struggling in Class A, the former top prospect was released. Cumulative arm wear had taken its toll.3

Vance, though, already held a degree from one of the nation’s most distinguished universities and, with the opportunity for further education, pursued it, rather than endure a further downward spiral in Organized Baseball. The result has been a rewarding career in landscape architecture and land planning. Today Vance remains active in his profession and supplements it with work in a global peace organization.

Gene Covington Vance4 was born January 5, 1947, in Lamar, Colorado, to Gene and Betty Louise Brown Vance. He was their second-born child and grew up with three sisters, Sharon, Corinne, and Carolyn. Lamar was and is the county seat and commercial center of rural Prowers County in the southeastern part of the state, bordering Kansas. Sandy’s father, Gene,5 who had grown up in Pueblo, 120 miles west of Lamar, helped run the local airport and also worked in construction and lumber yard sales. Betty, born in Lamar, was a homemaker. The Vance family, of Scotch-Irish ancestry, traces its American roots back to the Revolutionary War.6 They gradually migrated west to Colorado—grandfather Claude Covington Vance was a native of Kentucky; Claude’s wife Una was born in Kansas.

In 1953 Gene and Betty Vance “in search of a new life and opportunity,”7 moved the family further west, to Pasadena, California. Sandy played Little League baseball there on a team with future tennis great Stan Smith8. At Pasadena High, Vance excelled as a pitcher for coach Frank Matuszak, and in American Legion baseball for the Pasadena post team. His schoolboy success made him, on graduation in 1965, the California Angels’ second-round selection in that year’s inaugural June amateur draft.9 However, Vance, who had excelled academically in high school, opted to enroll at Stanford University. “The main reason I chose Stanford was for the education. I didn’t feel that I was physically or emotionally able to go to the pros. I anticipated that if I had what it took to play professional ball I could sign after that.”10 His Stanford coach, Ray Young, agreed, recalling later, “Sandy had a great arm when he was here, but he still had a lot to learn. Yet there was never any doubt that he’d make it to the pros.”11

At Stanford, the 6’2”, 170-pound righty joined a 1966 freshman team loaded with players who eventually signed professional baseball contracts. He was unbeaten (9-0), and then had an even better regular season (11-0, with an additional four postseason wins) as a sophomore as Stanford finished third in the 1967 College World Series.

In the summer of 1966, Vance pitched for the semipro Humboldt Crabs of Eureka, California; with three no-hitters from Vance, the team advanced to the National Baseball Congress tournament, finishing third nationally in the finals in Wichita. “Dandy Sandy”12 was voted the top pitcher in the tournament and named National Baseball Congress’s 1966 Sandlotter of the Year.13 Vance was inducted into the Humboldt Crabs’ Hall of Fame in 2013.14

Drafted after the 1967 Stanford season by the White Sox, Vance again elected not to sign. He leveled off to a 6-3 record as a junior in 1968 and led the Stanford staff in walks and wild pitches. But Vance, still very much on the radar of Dodger scouts Ben Wade, Red Adams, and Al Campanis,15 was Los Angeles’ second-round selection, No. 33 overall, in the June 1968 secondary draft.16 This time, he signed. As Vance remembered it nearly 50 years later, “There wasn’t much negotiation. My father, a traveling salesman, was my ‘agent.’ I was ready to sign because of being drafted previously. I signed for $28,500, [and] asked Al Campanis to throw in a used car, and he said ‘No.’ For a second-round draft pick, that shows how much has happened since those days!”17

The 21-year-old fireballer immediately went to work for the Ogden (Utah) Dodgers in the rookie-level Pioneer League. Managed by future Hall of Famer Tommy Lasorda and featuring Vance and fellow top draftees Bobby Valentine, Steve Garvey, Tom Paciorek, and Bill Buckner,18 Ogden nipped the Idaho Falls Angels by a half-game on the last day to win the 1968 Pioneer League pennant. Vance was the staff ace with a 14-3 record in 15 starts, 10 complete games, and 150 strikeouts in 118 innings. After winning 10 games in August19 as the Ogden season closed, Vance was promoted to the Dodgers’ Spokane Indians Pacific Coast League affiliate, where he got into two games, one a start, went 1-0, and had 8 strikeouts in 13 innings pitched.

Vance and Lasorda were close from the beginning and continue to stay in touch. Lasorda recalled the Ogden days: “Sandy’s always had a lot of class; he got that from his family—right moral upbringing and all that. Only thing he didn’t have was the killing instinct. I’d call to him out there [on the mound], ‘Sandy, you’re on the hill of thrills. The mound is your grocery store. Don’t let ‘em steal your groceries.’ And he’d tug his cap and bend his back and go to it. He learned.”20

For his part, Vance vividly recalls the day in 1969 in his first spring training when had just finished a workout; Lasorda summoned him to the Dodgertown major-league clubhouse and said he had somebody Sandy should meet. He remembers his jaw dropping as Don Drysdale, at the end of his 14 seasons as a workhorse of the Dodger pitching staff, took one look at Vance’s battered shoes and asked “Hey kid, who gave you those shoes, Ty Cobb?” Leaving the youngster flummoxed and Lasorda amused, Drysdale disappeared into the clubhouse and returned with a pair of his own shoes, which he tossed to Vance. “Here, see if you can fill these shoes. I hope to see you pitching with me someday,” he said. Vance remembered, “Maybe some young players would have bronzed those shoes and saved them, but I put them on and pitched with them until they were worn out, too.”21

Lasorda got his own promotion to manage Spokane for the 1969 season, replacing Roy Hartsfield. Reassigned there but no longer the ace,22 Vance got 18 starts as a mid-rotation starter and went 6-6 as Spokane finished two games under .500 and well off the 1969 Coast League North Division pace.

Still with Lasorda at Spokane for 1970, Vance was off to an excellent start with 16 strikeouts and one earned run in 15⅔ innings when the Dodgers needed a replacement for No. 2 starter Bill Singer, who had gone on the disabled list with infectious hepatitis.23 Calling the 23-year-old Vance “an outstanding young pitcher in our organization,”24 Dodger manager Walter Alston tabbed him as Singer’s replacement over 27-year-old Joe Moeller, who had made four spot starts during the 1969 season and who had shuttled between Los Angeles and AAA going all the way back to 1962.

The call-up came April 23, 1970, with Spokane in Tacoma and Los Angeles en route home from a series in Montreal. Lasorda saw something special: “I always call him ‘Dazzy’ because I told him I want to reincarnate one of the great names in baseball so Dodger fans hear [about] Dazzy Vance pitching for them again.” When Vance got into an airport limo for his flight to Los Angeles, Lasorda remembered, “I felt like my son was going off to college. We waved to each other as the limousine pulled away. We both had tears in our eyes.”25

Alston wasted no time in acquainting the rookie with the big time. The defending World Series champion Mets were visiting; the Dodgers had handled them 1-0 on both Friday and Saturday nights, with the series opener going 15 innings before Tom Haller drove in Wes Parker with the sole run of the game.26 Vance debuted in the Sunday, April 26, series finale—and, with 26,708 in Dodger Stadium, drew 1969 National League Cy Young Award winner and future Hall of Famer Tom Seaver as his mound opponent.

“I was tight and nervous,” Vance told reporters after the game, adding that it was the only game he had ever pitched in which the butterflies never went away.27 Once again Los Angeles scored a single run, but two of the Mets’ four hits off Vance left the ballpark.28 Taking the 3-1 loss, Vance wasn’t satisfied, and told reporters he wasn’t relaxed and didn’t feel the command he had earlier in the season at Spokane. Alston, though, praised the rookie: “Any time a kid can come in and pitch six innings like he did and give up four hits and walk only one, well, he’s done a darn good job.”29

Vance earned his first major league victory just four days later in his next start, a complete-game four-hitter at home against Montreal. The final score was 2-1, and Vance still remembers that lone Expos’ run. “Bobby Wine led off the third inning against me and hit a fly ball to right field that kept curving toward the foul pole. Andy Kosco was out there. As he chased the ball, he collided with the foul pole and you could hear the ‘bong’ all over the ballpark.”30 With the wind knocked out of him, Kosco lay in right field as Wine circled the bases for an inside-the-park home run.

Back in Dodger Stadium against the Giants on May 14, Vance drew another future Hall of Famer, Juan Marichal. While Los Angeles pounded Marichal for five runs in just over two innings, Vance cruised into the ninth, scattering eight hits in a 6-3 win. He started four more times through mid-June. Then Singer returned and Vance went back to Spokane.

He recalls that he started the first game of an August doubleheader against Hawaii in Spokane and lasted only four or five innings before Lasorda lifted him. Vance took a loss, but got Lasorda’s call in extra innings in the second game, pitching well for several innings before yielding the winning run and notching another loss. “I struggled a bit [back at Spokane] and came to believe that pitching in AAA was actually tougher in some ways than in the major leagues.”31 A few days after his double losses, Vance remembers, Singer broke a finger and Vance was recalled to the majors. “I use this story to tell young pitchers that no matter how bad things may look at any point, if you hang in there sometimes the strangest things can happen.”32

Vance finished the 1970 season in Los Angeles. His overall rookie effort was creditable: a 7-7 record over 115 innings, 20 appearances with 18 starts, and a 3.13 ERA that tied Singer for the rotation’s best. In 89 innings at Spokane he was 5-4 as Lasorda’s Indians ran away with the Pacific Coast League’s Northern Division pennant.33

The Dodgers’ front office thought so highly of Vance and 20-year-old rookie Doyle Alexander that they sent two pitchers who had combined for 16 wins in 1970—Alan Foster and Ray Lamb—to Cleveland for catcher Duke Sims in the 1970-71 offseason. At the Dodgers’ request, Vance had extended his 1970 workload by joining Escogido in the Dominican Winter League as a starting pitcher. The assignment lasted into January 1971, just a month before Dodger spring training opened. Vance pitched well enough in the spring to make Alston’s 1971 rotation and he won his first start on April 12 against the Cubs. But the extra winter work on top of pitching in the majors and Triple-A made the success short-lived. With his arm tired and sore,34 Vance started four days later and lasted only into the second inning against Houston. As the organization’s confidence in him plummeted, he got only one more start through the end of June. Then, still struggling with a sore arm, he was sent back to Spokane.

Illustrating the vicissitudes of baseball, Vance’s fellow prospect, Alexander, started the 1971 season in Spokane. He was called up in June days before Vance was demoted35 and then went to Baltimore that December as part of a trade for future Hall of Famer Frank Robinson. Alexander went on to win 194 major league games over 19 seasons and started Game One of the 1976 World Series for the Yankees against the “Big Red Machine” Reds.

Described in a 1973 Dodger organization press release as “as much a mystery to the Dodgers’ brass as to himself,”36 Vance, with his arm still sore, pitched ineffectively at Spokane the rest of 1971 and at Albuquerque37 in 1972. He was demoted to Class A Bakersfield in 1973 after one Triple-A inning for Albuquerque. The Dodgers released him outright from Bakersfield on May 25 after three lackluster starts. Although he had tried to remain upbeat throughout his precipitous trip down the ladder, Vance could never regain the form and reliability he had displayed in 1970. His major league ledger closed with a 9-8 record and 3.83 ERA in 141 innings. There would be no reincarnation of Dazzy Vance; by the time Lasorda took over from Alston as Dodgers’ manager at the end of the 1976 season to start the 21-year run that took him to the Hall of Fame, Sandy Vance was out of baseball.

“I put my whole heart and soul into baseball. Then one day it was over. When you leave baseball you leave part of your childhood behind, Vance remembered in 2013 for his Humboldt Crabs’ Hall of Fame profile.”38

“No one knew enough back then to help me re-strengthen my arm and rehab. There was much they didn’t know back then. I have heard that Nolan Ryan was one of the first pitchers to begin working out with weights and even he had to keep it secret from his team, or so the story goes. In those days they felt weight training would bulk you up too much and cause you to lose arm flexibility.”39

Vance had returned to Stanford after his Ogden season to complete his bachelor’s degree work in political science and finished in the top 15 percent of his class in 1969. Still only 26 when he was released, he pondered coaching possibilities and joining the Albuquerque radio team as a color commentator,40 but ultimately enrolled at Cal Poly Pomona, where he earned a master’s degree in landscape architecture in June 1977. He went to work with an environmental land planning and development firm in Newport Beach, California41 and is still active in the field, currently associated with the planning and development firm Kimley-Horn in Oakland.

With a talent in art and design, and “an interest in making a difference in the world,”42 Sandy Vance has applied his skills for nearly 40 years to the master planning, layout and design of environmentally sustainable new communities in towns and cities throughout the United States. His planning work also has taken him overseas to projects in Korea, Ghana, and Nepal. In Nepal, Sandy has teamed with a South Korean planner, Professor Kwaak Young Hoon, to help develop plans for a new World Peace City (Vishwa Shanti Nagrama) in Lumbini, the birthplace of the Buddha. This is an on-going project, approved by the Nepalese coalition government and designed to attract peace-loving citizens from different religious orientations around the world.43

With a talent in art and design, and “an interest in making a difference in the world,”42 Sandy Vance has applied his skills for nearly 40 years to the master planning, layout and design of environmentally sustainable new communities in towns and cities throughout the United States. His planning work also has taken him overseas to projects in Korea, Ghana, and Nepal. In Nepal, Sandy has teamed with a South Korean planner, Professor Kwaak Young Hoon, to help develop plans for a new World Peace City (Vishwa Shanti Nagrama) in Lumbini, the birthplace of the Buddha. This is an on-going project, approved by the Nepalese coalition government and designed to attract peace-loving citizens from different religious orientations around the world.43

Vance is also a member of the World Citizens Organization (WCO), founded by Professor Kwaak in the mid-1980s, encompassing a world-wide membership of individuals interested in peaceful and responsible cooperation and the exchange of ideas, culture, and goodwill.

Vance married his high school sweetheart Dee Hardcastle in Pasadena on October 11, 1970. They live in Oakland and have three children, Ryan, Erik, and Heidi. Ryan is a managing executive with FitBit, the company that markets mobile activity-tracking applications. Erik is an award-winning freelance science journalist published in National Geographic, Nature magazine, and Discover magazine. Heidi is a national marketing manager for Uber, the San Francisco-based online ride-sharing company. Dee Vance owns a move coordinating company in Northern California. Staffed completely by women, its goal is to assist clients with stress-free upsizing and downsizing.

Today, Sandy Vance, more than four decades removed from his fleeting success on the Dodger Stadium mound, follows the Dodgers, “especially when they’re winning or close to a pennant,” and enjoys watching Clayton Kershaw’s “unorthodox, but sound,” pitching mechanics.44

At Kimley-Horn he recently designed Castellina, a mixed-use development planned for Madera, California, in the San Joaquin Valley. In his leisure time Vance uses his artistic talent to paint; his most recent work is a mural for a new grandson’s nursery with a colorful world map featuring animals native to each region. He actively enjoys nature with backpacking and bicycling.

Vance still gives lessons to teens and teaches a philosophy somewhat at odds with today’s ideas about micro-management of pitchers. “I had three of the best pitching coaches of my day—Red Adams, Bob Shaw, and Roger Craig—and they taught me much that I can pass on to the kids. Lasorda (and I) still preach, ‘Never try to pace yourself.’ How would you like to come out of a game and sit in the locker room knowing you gave up a home run or a hit on a pitch that wasn’t your best? Make every pitch a masterpiece. Make every pitch as if it’s the last one you’ll every throw. Then if you run out of gas toward the end of the game or come out for some reason, you’ll know you gave it all you could.” And, on the growing practice he sees of coaches calling all pitches from the dugout for his students: “Part of the craft of pitching is learning to make your own decisions out there on the mound, and every pitcher should have that chance. A suggestion from the coach between innings is fine, but the pitcher himself needs to learn how to strategize his game and style. It’s the pitcher’s game and he should learn to own it.”45

Last revised: April 13, 2016

Author’s note

This biography has its roots at the intersection of my interests in the Atlanta Braves and notable starting pitching performances by rookies. As I skimmed through season logs for the early years of the Atlanta franchise, I came across a 1-0 Braves win against the Dodgers in Los Angeles on May 22, 1970. The losing pitcher had the intriguing name, especially for the Dodgers, of Sandy Vance. I researched further, and a SABR Games Project article resulted. Still intrigued by what I had learned about Sandy Vance’s life both before and after his time in Organized Baseball, I contacted him about the possibility of his participation in a biography. He graciously agreed, and this biography brings my original research meanderings to full circle.

Photo credits

Baseball card: Courtesy of The Topps Company.

“Sebastian’s World” by Sandy Vance: Courtesy of Sandy Vance.

Sources and Acknowledgments

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, I also utilized the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for box scores, player, team, and season pages, pitching and batting game logs, and other material pertinent to this biography. The Newspapers.com website provided access to many of the cited newspaper articles. All articles from The Sporting News were accessed through PaperofRecord.com. I gathered information on the Vance family through Ancestry.com at the Transylvania County Library, Brevard, North Carolina. My SABR colleague Gabriel Schechter collected material from Sandy Vance’s player file in the Giamatti Research Center at the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York. Finally, I would not have undertaken this biography without the enthusiastic assistance of Sandy Vance, with whom I communicated by email from July 2015 through February 2016.

Notes

1 Dazzy Vance, inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1955, pitched in Brooklyn from 1922 through 1932, then returned for an encore in his final season in 1935. Sandy Koufax, inducted in 1972, pitched his first three Dodger seasons in Brooklyn, then pitched in Los Angeles from 1958 through 1966, when he retired at age 30 after a 27-win season.

2 Gordon Verrell, “Sandy Vance: Down but not out—yet,” Long Beach (CA) Independent, March 22, 1973, 44.

3 Sandy Vance, email, November 13, 2015.

4 “No, I’m no relation to Dazzy Vance, and I got the name Sandy the day I was born,” a smiling light-haired Vance, recently arrived in the majors, told writer Gordon Verrell. “My grandfather decided to call me Sandy instead of my real name, Gene, and that was that.” Gordon Verrell, “Sandy Vance May Be Dodger Repeat of Daz and Koufax,” The Sporting News, May 16, 1970, 10; John Y. Brown, Betty Vance’s father, bestowed the name. “He walked into the hospital on day one, saw my hair color, and named me Sandy.” Sandy Vance, e-mail, February 5, 2016.

5 Major Gene Covington Vance Sr. piloted numerous bombing missions in Europe during World War II. Vance, November 13, 2015.

6 Ibid.

7 Vance, February 5, 2016.

8 Sandy and Stan played for the league’s “Dodgers” team. Pasadena (CA) Independent, October 23, 1968, 6.

9 The Angels offered a bonus estimated at between $60,000 and $75,000. Pasadena (CA) Independent, July 7, 1965, 24.

10 John Arthur, “Sandy Vance Goes To The Top,” Stanford (Palo Alto, CA) Daily, May 28, 1970.

11 Ibid.

12 Eureka-Humboldt (CA) Standard, June 17, 1966, 13.

13 Player data card, 1972, Sandy Vance file, Giamatti Research Center, Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

14 HumboldtCrabs.com, Sandy Vance profile, accessed March 28, 2016.

15 Player data card, 1972, Sandy Vance file, Giamatti Research Center, Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

16 Vance was selected one pick ahead of his college catcher, Michael Schomaker. Schomaker, selected by the Angels, never reached the majors.

17 Vance, February 5, 2016.

18 The Dodgers also drafted perennial NL All-Star Ron Cey in 1968. Cey’s first professional assignment was to Tri-City of the short season (Low-A) Northwest League rather than Ogden.

19 “I would start, then relieve two days later—that’s how I was able to pull it off.” Vance, February 5, 2016.

20 Ira Berkow (N.E.A.), “It’s Sandy Vance—Double Namesake,” Hope (AR) Star, May 16, 1970, 5.

21 Vance, November 13, 2015.

22 Left-handers Lawrence Staab, 25, and Fred Norman, 26, each won 13 games for Spokane in 1969. Norman had already been in the majors briefly with the Kansas City Athletics and Cubs and would return as a key member of the Cincinnati Reds’ rotation in the mid-1970s. Lawrence Staab never reached the majors.

23 Dodger reliever Pete Mikkelsen apparently contracted hepatitis on a vacation trip to Mexico and required hospitalization during 1970 spring training. Singer had visited Mikkelsen in the hospital, but showed no immediate symptoms. Singer pitched through spring training and started the Dodgers’ second game of the season on April 8. He started again on April 12 and in Cincinnati on April 16, but lasted only four innings. He was diagnosed with infectious hepatitis at that point and went on the disabled list on April 22. Melvin Durslag, The Sporting News, May 16, 1970, 2.

24 Gordon Verrell, “Singer’s Illness Shakes Up Dodgers,” The Sporting News, May 9, 1970, 14.

25 Berkow, May 16, 1970.

26 The run came earlier on Saturday; Maury Wills drove in Billy Grabarkewitz in the third inning.

27 Ross Newhan, “Vance Debut: Problems but Promise,” Los Angeles Times, April 27, 1970.

28 Donn Clendenon’s leadoff home run in the second inning was the first hit Vance yielded in the majors. After the Dodgers tied the game 1-1 in the fourth, Mike Jorgensen led off the New York sixth with a home run. The Mets’ third and final run came on Bud Harrelson’s steal of home later that inning.

29 Verrell, May 16, 1970.

30 Vance, November 13, 2015.

31 Vance, February 5, 2016.

32 Ibid.

33 Spokane won the Northern Division by 26 games over Portland, then on September 4-7 when Vance was back in the majors, swept the Hawaii Islanders in four games to win Spokane’s first Pacific Coast League championship.

34 Vance, November 13, 2015.

35 Vance recalls: “Doyle was young and strong, while my arm was fading then.” Vance, February 5, 2016.

36 Bakersfield Dodgers press release, “Ex Major-Leaguer Joins Bakersfield Mound Staff,” May 28, 1973, Sandy Vance Hall of Fame file.

37 The Dodgers moved their Pacific Coast franchise from Spokane to Albuquerque in 1972. They operated the Indians as a short-season Class A franchise in the Northwest League that season. Spokane returned to Class AAA as Texas Rangers’ affiliate for 1973.

38 HumboldtCrabs.com, Sandy Vance profile, accessed March 28, 2016.

39 Vance, February 5, 2016.

40 Long Beach (CA) Independent, June 16, 1973.

41 “Sandy Vance—Not a Koufax or Dazzy,” unattributed and undated clipping, Sandy Vance Hall of Fame file.

42 Vance, November 13, 2015.

43 Ibid.; Samik Kharel, “Plan to Build Lumbini As Global Peace Hub Unveiled,” http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com, June 26, 2014; http://lumbinitrust.org/articles/view144, accessed January 1, 2016.

44 Vance, February 5, 2016.

45 Ibid.

Full Name

Gene Covington Vance

Born

January 5, 1947 at Lamar, CO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.