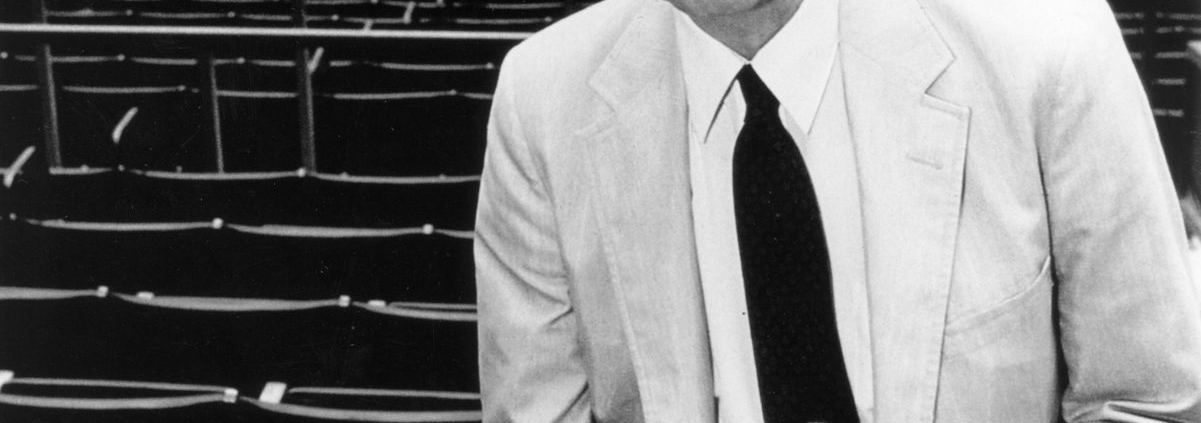

Si Burick

Si Burick’s byline adorned the sports pages of the Dayton Daily News in seven decades, from the 1920s to the 1980s. Over that impressive span, he demonstrated that it’s possible to have a big-league career without ever working in a big-league city. In 1983 he received the J.G. Taylor Spink Award “for meritorious contributions to baseball writing.”1 He became the first writer from a city without a major-league team to be so honored.

Si Burick’s byline adorned the sports pages of the Dayton Daily News in seven decades, from the 1920s to the 1980s. Over that impressive span, he demonstrated that it’s possible to have a big-league career without ever working in a big-league city. In 1983 he received the J.G. Taylor Spink Award “for meritorious contributions to baseball writing.”1 He became the first writer from a city without a major-league team to be so honored.

Simon Burick was born on June 14, 1909, the first of six children – three sons and three daughters – of Rabbi Samuel F. and Lillian Burick, Russian Polish immigrants who settled in Dayton in the first years of the 20th century. The rabbi served as spiritual leader of Beth Abraham Synagogue for more than 50 years, setting an example for his son’s life.

After graduating from Stivers High School, Burick enrolled in the pre-med program at the University of Dayton. By then he’d already gotten a taste of the newspaper business, working as a $2-a-week correspondent for his high school and receiving his first byline on August 26, 1925. He worked summers at the Daily News as an office boy, telephone operator and finally a sportswriter. Soon he caught the eye of the paper’s publisher, James M. Cox, former Ohio governor and 1920 Democratic presidential candidate. When the sports editor’s job opened up, Cox offered it to him at $30 a week, twice his previous salary.

Burick jumped at the chance and never returned to college. Of his parents’ reaction, Burick said, “I don’t think they ever quite understood why their son chose sports writing as a means of making a living, but they never discouraged me.”2 For himself, he said, the decision “was a boon to humanity. I would have been a terrible doctor.”3 His first column appeared on November 16, 1928. Late in his career he observed that he’d received a promotion when he was 19 years old and never gotten another one.

The job was a learning experience but Cox encouraged his energetic protégé to expand his horizons beyond Dayton and, in time, to regard the world as his beat. Burick covered his first Opening Day at Cincinnati’s Redland (later Crosley) Field in 1929. Rereading the resultant article years later, he said, “It was schoolboy writing that demanded editing and didn’t get it.”4

Other “firsts” came rapidly in the next few years – first Kentucky Derby in 1929, first World Series in 1930, first heavyweight title fight in 1931. Meanwhile on June 28, 1935, he married Rachel “Rae” Siegal, a schoolteacher from New York; their marriage would last nearly 50 years and produce two daughters, Lenore and Marcia.

With Cox’s backing, whenever there was a major sporting event of any kind anywhere in the country, Burick was there. His personal box score would eventually encompass all but two Kentucky Derbys through 1986, major bouts of heavyweight champions from Max Schmeling to Muhammad Ali, all but one World Series from 1934 to 1984, the first 20 Super Bowls, five Summer Olympic Games from Rome (1960) to Los Angeles (1984), and the Cincinnati Reds’ opening game every year from 1929 to 1984.

He was never a baseball beat writer. But of all the sports he wrote about, baseball was his first love. His office was 52 miles from Crosley Field, but he was a regular presence in the clubhouse and the press box there. One of his big stories was a bombshell he dropped on February 17, 1948, after Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey spoke at Wilberforce University near Dayton. Speaking at a historically Black institution after the conclusion of Jackie Robinson’s first season with the Dodgers, Rickey recounted for the first time a vote major-league owners had taken in the fall of 1945 opposing the desegregation of Organized Baseball.5

Baseball officialdom had long disingenuously denied that there was any rule or formal policy against signing Black players and when the story went national, the other owners exploded with indignant denials.6 Rickey expressed surprise at the reaction, but the writer was convinced that Rickey had made his comments with calculated intent. Years later Burick wrote that at one point during his speech, Rickey turned to him and said, “What I am saying, Si, is on the record. If your pencil is not sharp, I will sharpen it for you.” Afterward, he gave Burick his notes to help in writing Si’s column.7

Burick went to spring training with the Cincinnati Reds for the first time in 1937. Before long the annual trip became a family affair. Si and Rae would take the girls out of school and they would all go together. Looking back as an adult, the Buricks’ younger daughter wrote an engaging reminiscence for the New York Times about getting to know not only the Reds players but other nice men including Mr. Musial, Mr. Schoendienst and Mr. Frisch, an older gentleman who liked to talk baseball with seven-year-old Marcia while they collected seashells on the beach. The girls took their schoolwork with them to Florida; in third grade, Marcia learned long division by figuring batting averages.8

Si wasn’t a collector, but one artifact he held onto reflected his appreciation of baseball history. He met Babe Ruth at spring training in 1948, months before the Baminbo’s death, and got his autograph on a ball. When Henry Aaron broke Ruth’s career home run record in 1974, his signature was added to the ball. And when Burick accompanied the Reds on a tour of Japan in 1978, he got the ball signed by the Japanese home run king Sadaharu Oh.9

Burick’s writing was characterized by gentle, self-deprecating humor; the man himself was known for a love of wordplay and atrocious puns. Until the mid-1970s, he called his column Si-ings. One of his favorite passages was inspired by the Triple Crown-winning thoroughbred Secretariat:

“This horse is the opposite of everything I am. He is young, he is beautiful, he is fast, he has hair, he has strong legs, he is durable, he has a large bank account. And his entire sex life is in front of him.”10 When a topless dancer invaded the playing field during the 1970 Super Bowl, Burick looked on as four police officers ran her down. “And they took her away two abreast,” he observed.11

He was a role model and a father figure to generations of young sportswriters at the Daily News. Rae referred to them as “Si’s boys.”12 When they in their turn began to travel the country, they were immediately welcomed and accepted as representatives of “Si’s paper.”13 He was also a painstaking writer and teacher who never left a participle dangling and frowned on “win” as a noun.

“It was as if he invented who and whom,” one of his boys wrote.14

In 2003 one of the boys, longtime Daily News baseball writer Hal McCoy, following the trail Burick had blazed, received the Spink Award. In his acceptance speech, McCoy acknowledged Burick’s importance as a mentor. Burick was respected for the quality of his work, admired for his unfailing honesty and fairness, and beloved for his innate decency.

“He has stood above the easy putdown and cheap, synthetic anger,” wrote Arnold Rosenfeld, editor of the Daily News. “When he speaks in rare outrage, the reader can know he means it, and that something’s wrong.”15 Joe Falls, sports editor and columnist for the Detroit News, was more succinct. Members of the nomadic fraternity of sportswriters, he said, regarded Burick as a hero.16

“I kind of hang around Si and hope he doesn’t notice it,” Falls wrote. “I keep hoping some of him rubs off on me.”17

Burick received job offers from New York and elsewhere, but he stayed put. One of the last writers to serve as both sports editor and featured columnist at a metropolitan newspaper, he typically turned out five columns a week, sometimes seven. By 1982 he estimated he had written 13,000 columns for the Daily News, averaging 1,000 words each. A fair guess would be that by the time he died he had written 15 million words for one newspaper.

Starting in 1935, he also hosted a 15-minute show on local radio (and later television) five days a week. The show aired for the 5,000th time in 1958 and continued until 1961.

His workload at the paper left little time for other writing. His byline cropped up occasionally in The Sporting News or the Cincinnati Reds yearbook. He collaborated on two slender books, Alston and the Dodgers (1966) with longtime friend and southern Ohio native Walter Alston; and The Main Spark (1978) with Reds manager Sparky Anderson.

In 1982 the Daily News published a collection of his columns. For Byline: Si Burick – A Half Century in the Press Box, the writer modestly winnowed a near-lifetime’s work down to barely 60 articles. In addition to the Rickey story and assorted examples of Reds coverage, the baseball pieces included Burick’s coverage of Bobby Thomson’s home run, Don Larsen’s perfect game, and Casey Stengel’s 1958 testimony before a Senate committee.

Burick increasingly viewed sports in the context of world events, writing columns about the death of John F. Kennedy, civil rights protest at the 1968 Olympics, and terrorism at the 1972 Olympics. On rare occasions he stepped away from sports altogether. In 1971, when the Daily News mounted a series about Dayton’s changing neighborhoods, Burick volunteered a bittersweet 2,000-word essay on the near east side, where he grew up. As feared, he found that all the landmarks of his youth had disappeared. He said the piece generated more reader reaction than anything else he ever wrote.18

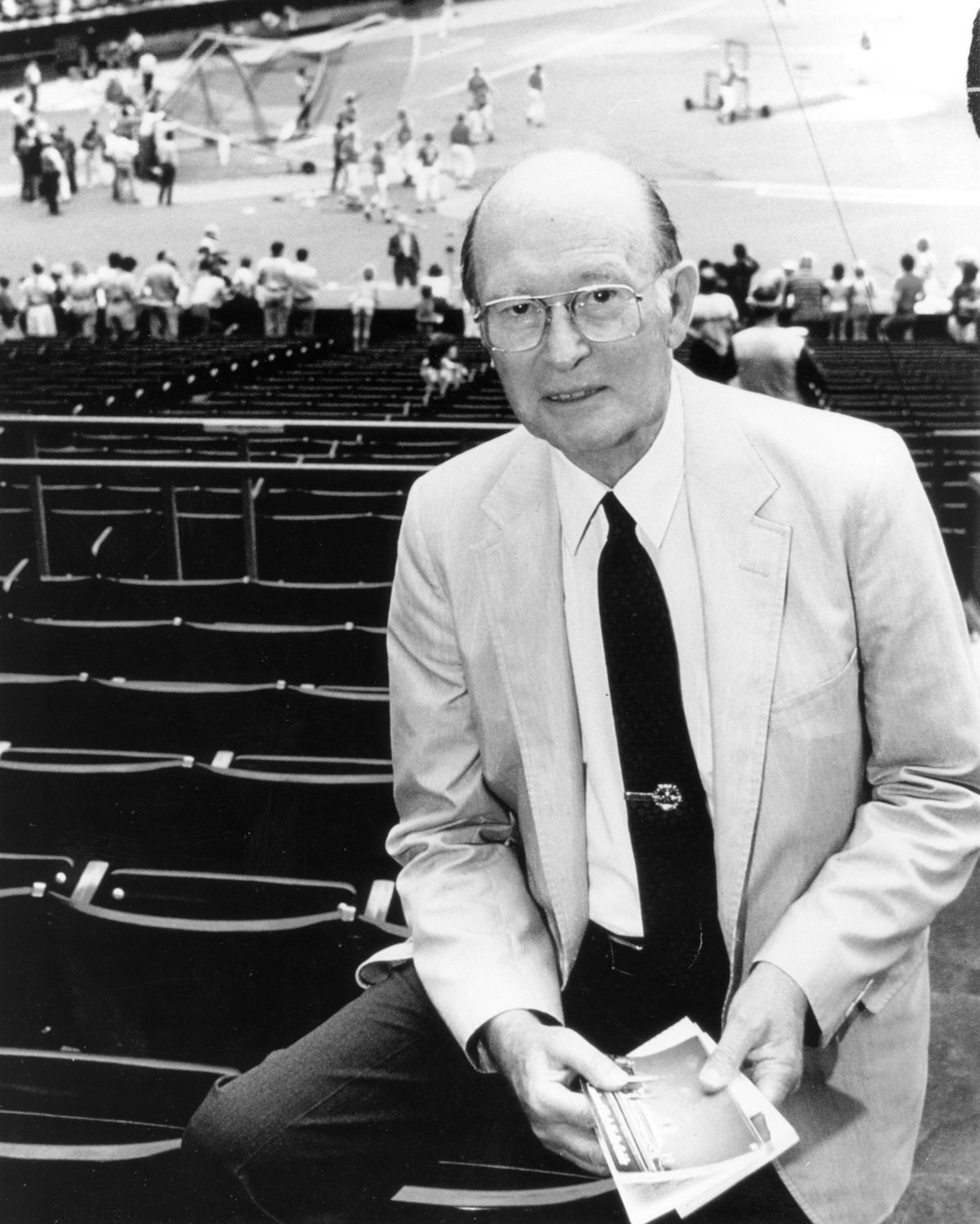

As the years added up, so did the honors. He was represented in Irving T. Marsh and Edward Ehre’s annual Best Sports Stories anthology 16 times. He was named Ohio Sportswriter of the year by the National Sportswriters and Sportscasters Association 18 times, including 14 in a row from 1962 to 1975. The University of Dayton, which had earlier created a Si Burick Award to be given to a top student in journalism or broadcasting, presented him with an honorary doctor of humane letters degree in 1977. The Reds hosted Si Burick Night at Riverfront Stadium on August 30, 1983. He received the Red Smith Award from the Associated Press sports editors in 1986.

His long string of consecutive Opening Days in Cincinnati was broken in 1985, when he traveled to Salisbury, North Carolina, to be inducted into the National Sportswriters and Sportscasters Association Hall of Fame.

The pinnacle came on July 31, 1983, when Burick accepted the Spink Award at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Busloads of admirers came from Dayton and from Northampton, Massachusetts, where daughter Marcia lived. Inductees on the same day included his old friend Walter Alston, who was unable to attend because of ill health.

“Mine has been a career of joy,” Burick told the crowd. “Joy has been the keynote of my life as a sportswriter and as a baseball writer. I never considered it hard work. I never considered it work.”19

Burick remained healthy and active well into his 70s. He continued to travel widely. He never adapted to computers. He tapped out his stories on a typewriter; when he was on the road, he dictated them over the telephone, then called back to the office an hour later to see if there were questions.

His wife died in 1985. He was hospitalized for 82 days after open-heart surgery in 1986 and was subsequently diagnosed with leukemia. Through it all he carried on, continuing to write an occasional column from home. In nearly constant pain,20 he went to Washington, DC, on October 20, 1986, when he was among 14 veteran sportswriters and sportscasters invited to a White House luncheon with President Ronald Reagan to mark the 100th anniversary of the publication of The Sporting News.21 The last event he covered in person was the Ohio State-Michigan football game on November 22, 1986. He wrote about watching the game with former Ohio State coach Woody Hayes, another old friend.

Si Burick never retired. His final column appeared on December 7, 1986. He died three days later.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Bruce Harrris and fact-checked by Terry Bohn.

Notes

1 Si Burick plaque at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

2 Si Burick, Spink Award acceptance speech, July 31, 1983, on file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

3 Burick, Byline: Si Burick – A Half Century in the Press Box (Dayton, Ohio: Dayton Daily News, 1982), iii.

4 Burick, Byline: 3.

5 Burick, “Rickey Tells Story of Signing of Robinson,” Dayton Daily News, February 17, 1948: 16.

6 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 451-52.

7 Burick, Byline: 147.

8 Marcia Burick Goldstein, “Spring Training: Bonus for a Little Girl,” New York Times, February 26, 1978: 359.

9 Bill Madden, “A Gem of an Autographed Ball,” The Sporting News, November 25, 1978: 53. See also Joe Falls, “Burick is Dayton,” Dayton Daily News Magazine, July 24, 1983: 16.

10 Burick, “Super Bowl Beautiful; So is Bogie Busters Bash,” Dayton Daily News, June 13, 1973: 10.

11 Dave Kindred, “Of Human Jukeboxes and the Hammer,” The Sporting News, January 27, 1992: 6.

12 Gary Nuhn, “As Good a Boss as This Writer Could Ever Want,” Dayton Daily News, December 12, 1986: 6.

13 Hal McCoy, “Si Burick,” Dayton Daily News, August 25, 1985: 97.

14 Nuhn.

15 Arnold Rosenfeld, “Our Si Burick Gets His School Letters,” Dayton Daily News, April 24, 1977: 16.

16 McCoy.

17 Joe Falls, “Burick is Dayton,” Dayton Daily News Magazine, July 24, 1983: 14.

18 Burick, Byline: 167.

19 Burick, Spink Award speech.

20 Mark Katz, “Si’s Last Days Truly a Profile in Courage,” Dayton Daily News, December 12, 1986: 6.

21 Burick, “Reagan Recalls Foibles, Fun of Sportscasting,” Dayton Daily News, October 21, 1986: 1.

Full Name

Simon Burick

Born

June 14, 1909 at Dayton, OH (USA)

Died

December 10, 1986 at Dayton, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.