Stanley Cayasso

Stanley Cayasso (1906-1986) is one of Nicaragua’s baseball icons. Like Lou Gehrig, he was known as El Caballo de Hierro, The Iron Horse. A strong and durable hitter who also pitched in his younger days, Cayasso became a respected manager and coach. He came to symbolize his nation’s baseball because of his personality traits: honor, honesty, patriotism, and clean living.

Cayasso never made it to the major leagues. In fact, he had only one professional at-bat, at age 50 as Nicaragua formed its first pro league in 1956. By then he was a coach. Yet, like at least several of his countrymen before Dennis Martinez made his big-league debut in 1976, he was “an uncrowned king” (to quote novelist Sergio Ramírez).1 In the opinion of Nicaraguan baseball historian Tito Rondón, “The two lost major-leaguers of the ’30s and ’40s were [José Ángel] ‘Chino’ Meléndez and Stanley Cayasso, according to legend (and, I believe, facts).”

That opinion was supported by Cuban pitcher Conrado Marrero, who (as of 2006) was one of the few men alive to have faced Cayasso. That year Marrero told Managua sportswriter Edgard Tijerino, “I am sure that Cayasso would have been a bright light in whatever league. He is the best Nicaraguan player that I have seen.”2 As is true of another Nicaraguan star of that era, Eduardo Green, if that seems faint praise, it shouldn’t.

Oliver Stanley Livingstone Cayasso Guerrero was born on September 17, 1906, in Bluefields. This town is the heart of Nicaragua’s English-influenced Atlantic coast. Its population is largely Afro-Caribbean, thanks to an influx of runaway slaves and free blacks from the British West Indies, Jamaica in particular. Stanley’s father was Wilfred Cayasso, known as “Captain” because he ran a commercial boat business, transporting passengers and cargo along the coast. His mother, Sofía Guerrero, had two boys and three girls. 3

The 2003 book Leyendas del Béisbol Caribeño Nicaragüense (Legends of Nicaraguan Caribbean Baseball) draws on an interview that local baseball writer Julio César Miranda conducted with Stanley’s brother George, who passed away at the age of 96 in 2004. It said, “Those who knew this exemplary family say that they were very religious, belonging to the Moravian Church, and the children were taught values like unity, respect and solidarity. They had some money, as Wilfred owned five boats. . .Four were locally built and the largest one was purchased in the United States.”

Stanley and George (also known as Jorge) both played baseball. Starting in the late 1880s, the Atlantic Coast population (costeños) forged a strong connection to the sport. Eduardo Green (born Edward; father of 1980s big-leaguer David Green) was also from Bluefields. Eventually, three of Nicaragua’s 14 major-leaguers — Albert Williams, Marvin Benard, and Devern Hansack — would come from there or other nearby spots on the coast. Jorge told Julio Miranda that he and Stanley loved to read the newspapers that arrived weekly (several old editions) from Managua. Together with their father, the lads promptly looked up the sports page, especially baseball. They “obsessed about being able someday to play against those clubs, Bóer, Managua, Granada, and San Fernando.”

In 1925, Stanley Cayasso jumped from youth ball to playing against men. According to Nicaraguan author Guillermo Segundo “Kaiser” Uriarte, he played with a team called Hound. Stanley stood 5’11” and weighed 170 pounds as a young adult, though as years went by, he would bulk up to around 200 pounds. He batted and threw left.

Wilfred Cayasso had a team called Nine Strong in Bluefields, which played in the local league against other teams called Acorn, Long Star, Yellow Rose, Zelaya, Titan, and Pirates. The Cayasso brothers and their friend Herbie Carter joined a team called “Navy.” They became the archrivals of Acorn — and the most storied club of the Atlantic Coast’s early baseball history.

In 1930, Navy took Wilfred Cayasso’s gasoline launch Elk to play a five-game friendly series in Puerto Limón, on the Atlantic coast of Costa Rica. They made a couple of trips there, possibly the second one in 1931. Then in 1932, a landmark event in Nicaraguan baseball annals took place. The Elk brought the 28-man Navy squad, captained by Jorge, to the nation’s “Pacific” (i.e., western) region for a barnstorming tour. It was the second time that a team from the Atlantic Coast had made this expedition. Some 15 years earlier, another group — even featuring a half-Jamaican one-armed player — came to the Pacific. Little is known about that prior team, though.

The Elk headed south to San Juan del Norte (also known as Greytown), on the border with Costa Rica. It then went up the San Juan River — and its rapids — to Lake Nicaragua, finally docking at Granada. The team took the train to Managua, where the organizer of the tour, Francisco “Pancho” Olivares, awaited them, along with a reception committee and numerous fans. Also aboard was the Navy Jazz Band, which caused a sensation with its music.4 Many of the ballplayers — including Jorge, who played banjo and guitar — doubled as band members.5 On August 16, 1932, the band made its debut at the “Field del Retiro” ballpark, entertaining the fans attending the first game of the final series for the championship between Bóer and San Fernando. On the 20th, Navy traveled to León and beat the locals 8-4; the winning pitcher was Stanley in relief of Jorge. The Elk, meanwhile, received a special permit to work on the lake and earn the keep of the sailors and the boat.

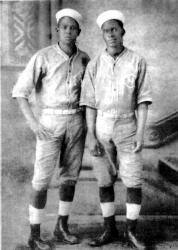

The club had no actual military connection, but the players wore sailor caps to go with their standard baseball uniforms, as seen in a charming photo of the Cayasso brothers from Julio Miranda’s archives. “The cute sailor hats were obviously an advertising gimmick,” said Rondón. “A picture of a game shows Navy wearing normal baseball caps.” However, they did use the sailor hats on occasion to amuse the fans.

Navy was highly successful in the Pacific side. They were even accused of witchcraft and had a “black bat” burned, sprayed with holy water and buried — they still won. Finally, they played a championship series against Bóer. The foremost local historian, Jorge Eduardo Arellano, told the story in his 2007 book, El Béisbol en Nicaragua. After the first two games, the agent for Pan American Airways in Nicaragua, a former Army captain named Richard Price, flew to Bluefields on his own to bring back reinforcements for Navy. One was Allen Álvarez from the team Alert, whom many regard as the best costeño catcher ever. Another was Acorn’s Timothy Mena (born 1897), another longtime national star who had big-league talent.6 The two men were instrumental in Navy’s record of 14-6 with two ties over more than four months.7

Navy was highly successful in the Pacific side. They were even accused of witchcraft and had a “black bat” burned, sprayed with holy water and buried — they still won. Finally, they played a championship series against Bóer. The foremost local historian, Jorge Eduardo Arellano, told the story in his 2007 book, El Béisbol en Nicaragua. After the first two games, the agent for Pan American Airways in Nicaragua, a former Army captain named Richard Price, flew to Bluefields on his own to bring back reinforcements for Navy. One was Allen Álvarez from the team Alert, whom many regard as the best costeño catcher ever. Another was Acorn’s Timothy Mena (born 1897), another longtime national star who had big-league talent.6 The two men were instrumental in Navy’s record of 14-6 with two ties over more than four months.7

It’s worth noting that another of the Navy players was Julián Benard, great-uncle of Marvin Benard, who played in the majors from 1995 to 2003.8 Author George Gmelch (who heard stories firsthand from Jorge Cayasso not long before his death) and Julio Miranda have also noted the ongoing importance of the Navy team on a national level. Gmelch wrote of the costeños’ “elegance, athleticism, and speed.” In early 1933 the Atlantic ballplayers realized the Pacific side was the big stage, and a number of them migrated west, changing the face of Nicaraguan baseball forever.

When Stanley Cayasso arrived in the Pacific in 1932, he was a centerfielder and pitcher. He played the 1933 season for Managua. Late in the year he joined the new “Big Khaki Machine” — the team called General Somoza, after National Guard director (and avid baseball fan) Anastasio Somoza García. Stanley played with this club from 1934 until it disbanded in 1938.

Five costeños became the first men ever from their region in the Nicaraguan national team in 1935. Along with the brothers Cayasso and Herbie Carter, they were John Williams (3B) and Culvert Newell (LF). They took part in the 1935 Central American Games in El Salvador. As a pitcher, Stanley Cayasso established a record by striking out 18 batters against the host nation’s team on March 31, 1935, at Flor Blanca Stadium in San Salvador. The Salvadorans’ manager was former Cincinnati Red Manuel Cueto, the first man associated with the major leagues to visit Nicaragua (1933). Tito Rondón said, “Because Cueto lobbied to exclude Nicaraguan ace Chino Meléndez from the games, Cayasso was overused and blew out his arm. He did not have time to be a frontline pitcher like Babe Ruth because he only played three seasons before he sacrificed his arm for his country.”

Three years later, the Nicaraguan national squad made an epic four-day journey by train, ferry (which caught fire and sank), and horseback through Costa Rica to Panama for the 1938 edition of the Central American Games. As Nicaraguan baseball historian Bayardo Cuadra told George Gmelch, the mini-odyssey formed a long-lasting esprit de corps.9

In 1939, Team Nicaragua took part in the second Amateur World Series (now known as the Baseball World Cup). The pinoleros went 3-3, finishing second behind undefeated Cuba. In its coverage of the deciding game, the New York Times wrote, “A home run, the first of the series, by stocky Cayasso, the Nicaraguans’ first baseman, accounted for the visitors’ lone run in the fourth inning.”10 The only other homer of the tournament was hit by pitcher-outfielder Jonathan Robinson, another of Nicaragua’s “lost major-leaguers” of the time. Robinson was born in 1911 in Puerto Limón. His father was Jamaican (as was Eduardo Green’s) and his mother was from San Juan del Norte. The Robinsons later moved to Bluefields.11

Cayasso remained a star of the national amateur team for years to come. Returning to Havana in 1940, Nicaragua (9-3) again finished second to Cuba. El Caballo de Hierro led all hitters with 19 base hits. He appeared in a total of 11 Amateur World Series from 1939 to 1953, winning another individual honor in 1947 when his 12 RBIs led the tournament. The only older player on the team was the ageless Timothy Mena, still pitching in the 1948 tournament at age 51 (he remained active as a pinch-hitter until 1955). In later life, Cayasso managed Nicaragua’s 1965 and 1969 entries.

Cayasso also participated in the 1950 Central American and Caribbean Games in Guatemala, where Sandy Amorós starred for Cuba. Against Costa Rica, Stanley tried to score from second on a short single; he was knocked unconscious for a while after crashing at home with the catcher. The Costa Ricans won 2-1 but Stanley was hailed as a fearless hero. At the Pan-American Games in Buenos Aires in 1951, Cayasso hit a memorable homer against the United States, represented by Wake Forest College. His three-run blow in the sixth inning provided a necessary cushion as Nicaragua hung on to win, 9-8.12 The 44-year-old finished the tourney batting 16-for-32 with two homers.13

Cayasso’s career at home was even more significant. After the General Somoza team was disbanded — by the dictator himself, who wanted the teams more evenly matched — he was sent to the team representing Carazo, the department where Somoza was born. He pitched for Carazo a little in 1940, and possibly in 1941, though his days on the mound had effectively ended in 1935. The team’s star hurlers were Chino Meléndez and Jonathan Robinson.

In 1941, the Atlantic champions, Zelaya, faced Bóer for the national title. Since Zelaya was the name of the country’s large Atlantic department, in effect this may have been a costeño all-star squad; their best players were already in the Pacific. Stanley reinforced Zelaya; after the series, Eduardo Green, then a shortstop, stayed on in the nation’s capital.14 They joined a team called Olímpico.

Then, in 1942, Cayasso and Green became part of the club that would become the nation’s equivalent of the Yankees: Cinco Estrellas.15 The Nicaraguan National Guard chose the name for Somoza, the nation’s only five-star general. Tito Rondón pointed out something else that sounds logical, though he acknowledged it as hearsay. “I don’t think Olímpico changed names. The new team signed a bunch of people and raided all the best players from Olímpico, making it disappear.”

Cayasso thereafter remained associated with Cinco Estrellas, which won nine national amateur championships in 11 years from 1944 to 1954. He made his debut as the team’s manager in 1944 and was skipper throughout this run of dominance. The players got paid for their service in the army. Fans called them the Presidential Guard.16 Said Rondón, “If you had good seasons, you advanced in grade so that your pay increased, which is why Cayasso made lieutenant.”

As a player, Stanley’s main position remained center field until 1945. He was Terry Moore’s opposite number when the Cardinal became the first active big-leaguer to visit Nicaragua in 1943.17 He then moved to first base. “When he was young, no doubt he was a capable fielder and maybe more,” stated Tito Rondón. “But his heyday was from 1939 to 1953, when he was 33 to 47 years old. By then Cayasso’s fielding was poor.

“When I was growing up, his legend was huge, and I also believed the fielding part. Until one day in about 1976, talking to an old pitcher, I happened to mention that. He looked at me like I was from Mars. ‘Cayasso, a good fielder? Hah! He cost me an international game! A sorry foul ball near the bag and he couldn’t catch it! And then they lit me up…’

“Alberto Miranda, who was a good-fielding first baseman in the ’40s, told me a funny story. ‘One time I made the national team, and as usual Cayasso was named captain. When we were at the hotel at the city where the competition was going to be held, he started to call every player, one by one, to his room for a talk. When my turn came, I entered and said, ‘Good evening, how may I help you?’ He answered, ‘Sit down, we are going to discuss your fielding.’ I said, ‘What? You, discuss fielding with me? You don’t field half as good as me. I thought you were going to give me hitting tips! Good night!’ And I left. And he did not discipline me because he knew I was telling the truth.’”

Rondón added, “Cayasso did not smoke or drink and was very disciplined, so Eduardo Green called him occasionally ‘La Cayassa,’ a woman. Sort of like Lady Baldwin [the 19th-century U.S. player who did not smoke, drink, or curse either].”

Rondón offered yet another memory of the times. “The anti-Somoza daily La Prensa always tried to inflame opposition against the dictatorship from baseball fans by disparaging Cayasso and all of Cinco Estrellas. Then, when Cayasso became part of the national team for some international competition, he would become a hero again.”

By the time Jackie Robinson broke the major leagues’ color barrier in 1947, the Afro-Nicaraguan Cayasso was past 40. The Negro Leagues were little known in Nicaragua, but Puerto Rico and Mexico could have been options when he was younger. Yet he had always refused to turn pro because he felt it was his duty to represent his homeland in international competition.

Cayasso was removed as manager of Cinco Estrellas under unfair circumstances, as Tito Rondón recounted. “Inaugural day of the first pro season was Saturday, March 10, 1956, and Cinco Estrellas debuted the next day. On April 14, the Tigres, under Cayasso, were in first place with an 8-4 record. Cuban Emilio Cabrera landed in Managua, presumably on that day (the newspaper is dated the 15th). Many fans protested the change in managers. The truth was, the owners were cowed by some imported players, as the four Nicaraguan managers were doing a decent job but were fired in order to install imports. The owners thought the star players would rebel at having to serve under people with no experience in tougher leagues.”

Until the first Nicaraguan pro era ended in February 1967, Cayasso loyally remained a fixture as coach with Cinco Estrellas.18 Later in 1956, he got his only pro at-bat. “Coaches and managers were allowed to play in those days,” said Rondón. “One time the Tigres had a runner on third with less than two outs in a close game, and Cayasso put himself in to pinch hit. He grounded to second and the second baseman committed an error, and he was credited with an RBI.” (Apparently the scorer ruled that the runner would have crossed the plate anyway.)

Especially after it joined Organized Baseball in 1957, the Nicaraguan league attracted much talent from the U.S. and Cuba, among other places. Cayasso served under Johnny Pesky, who came down to manage Cinco Estrellas in the winter of 1959-60. He was the American’s interpreter; Pesky recalled him as “a very fine man” in 2004.19 Tito Rondón also remembered how that season, Stanley “put on a show during batting practice that amazed everyone!” In the last season of the first pro era, 1966-67, the manager was a Cuban, Julio “Jiquí” Moreno. Cinco Estrellas won the championship just before a brief but bloody revolt broke out.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Cayasso also managed First Division amateur teams, including Cabo Mejía, which traveled to Havana in 1958.20 Three years after the first pro league folded, in 1970, Nicaraguan baseball reorganized in the form of a high-level amateur league. Cinco Estrellas re-emerged, and it’s little surprise that Cayasso rejoined the team as coach. Starting in 1973, Stanley then managed in Matagalpa, which had joined the amateur league. He continued to coach that team in the 1980s, training ballplayers from the farming leagues around the area, and worked with Little League teams there. Outside of baseball, Stanley became an electrician. Even while managing the minor teams, he worked at this craft until an electric fan badly injured his fingers, at which point he retired.

Cayasso was married twice. He and his first wife, Elena Brooks, had three sons: Rodney (who passed away c. 2004 at the age of 79), Livingston, and Stanley. The latter two were aged 83 and 81 as of 2010. One time Livingston won a dance contest; his father remarked, “he won’t be a ballplayer, he is going to become a ballerina.” Livingston actually played a little; he was a very fast runner but never learned to hit. He was with Cinco Estrellas briefly and that was it. Stanley Sr. and his second wife, Guadalupe Castellano (who died in 1978), had three daughters: Francis, Carolina, and Martha. This union apparently began sometime in the 1940s.

In 1984, Nicaragua issued a series of seven postage stamps commemorating baseball stars. The highest denomination went not to Babe Ruth or Roberto Clemente, but to Stanley Cayasso.21 Unlike in the United States, one does not have to be deceased to receive this honor in Nicaragua — Cayasso died of natural causes two years later, on August 5, 1986.22 He had also been a diabetic in later life.

The national hero received the biggest funeral honors of any sporting figure in his country’s history. In the decree it issued to observe Cayasso’s death, the government recognized his importance and said, “Despite his advanced age, he continued to impart his knowledge and experience.”

In April 1986, Cayasso and two other revered old-timers, catcher Julio “Canana” Sandoval and pitcher Francisco “Zurdo” Davila, had received the Orden Eduardo Green Sinclair from President Daniel Ortega. The Nicaraguan government had established this award for sporting excellence in 1982, two years after the death of Eduardo Green. Posthumously, Stanley received credit for helping to develop the young hitters on the team of Productores de la UNAG, which made the First Division national semifinals in 1988-89.

In 1987, Managua held the first annual Stanley Cayasso Memorial Cup tournament, an international event that continued for at least three years (it appears to have ceased after the Sandinistas lost the national elections of 1990).23 One of Nicaragua’s youth leagues is also named for him, and even as of 2010, the Nicaraguan community of New York plays in a Stanley Cayasso softball league. The national stadium in Managua, which has carried the name of Dennis Martínez since 1998, honors its earlier local legend with the Stanley Cayasso room.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Bayardo Cuadra and Julio César Miranda for their prior research and for providing additional detail about Stanley Cayasso’s life and family. In November 2010, Julio César Miranda interviewed Stanley Cayasso Brooks and Bayardo Cuadra interviewed Livingston Cayasso Brooks and Carolina Cayasso Castellano. Continued thanks to Carlos Mena and José Daniel López.

Sources

Genet, Manuel and Edmundo Quintanilla Mendieta, Leyendas del Béisbol Caribeño Nicaragüense. Managua, Nicaragua: 2003.

Arellano, Jorge Eduardo. El Béisbol en Nicaragua. Managua: Academía de Geografía e Historia de Nicaragua, 2007.

Uriarte, Guillermo Segundo. El Baseball y Su Historia. Managua, Nicaragua: self-published, 1960.

Bjarkman, Peter C. A History of Cuban Baseball. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co.: 2007.

Bjarkman, Peter C. Diamonds Around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005.

Photo Credits

Cayasso as coach, late 1950s: Courtesy of Tito Rondón collection

Cayasso brothers with Navy: Courtesy of Julio César Miranda collection

Notes

1 Ramírez, Sergio. To Bury Our Fathers. First English translation published in London, England: Readers International, 1985. Originally published as ¿Te dió miedo la sangre? Managua, Nicaragua: Editorial Argos Vergara, 1977.

2 Tijerino, Edgard. “Cayasso, Ese Viejo Roble.” La Prensa (Managua, Nicaragua), August 12, 2006.

3 Miranda, Julio. “El Navy en el Pacífico.” El Nuevo Diario (Managua, Nicaragua), August 14, 2006. Arellano, Jorge Eduardo. El Béisbol en Nicaragua. Managua: Academia de Geografía e Historia de Nicaragua, 2007: 256.

4 Ibid.

5 Gmelch, George. Baseball Without Borders. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2006: 179.

6 Arellano, Jorge Eduardo. “El Navy: Primer Campeón Nacional de Béisbol.” La Prensa, September 15, 2007. Uriarte, op. cit.: 28. Sergio Ramírez also mentioned Mena as one of the “uncrowned kings.”

7 Five months, according to Arellano.

8 Miranda, op. cit. León, Sergio. “Muere Gloria Costeña.” La Prensa, June 20, 2003. Marvin Benard’s family moved from Bluefields to Los Angeles when he was 12 years old.

9 Miranda, op. cit.; Gmelch, op. cit., loc. cit.

10 “Cubans Triumph, 9 to 1; Turn Back Nicaraguans and Win Amateur World Series.” New York Times, August 25, 1939: 21.

11 Online biographical sketch of Robinson (http://www.manfut.org/museos/sf-RobinsonJonathan.html). As of 2010, there has never been a major-leaguer born in Costa Rica.

12 Tijerino, Edgard. “Cayasso truena, pero…” La Prensa, July 27, 2003.

13 Ruiz, Martín. “Aquel jonrón de Cayasso.” El Nuevo Diario, July 10, 2007.

14 Genet, Manuel and Julio Miranda. “El ‘Chino’ ganó 4 juegos.” El Nuevo Diario, June 9, 2000.

15 Miranda, Julio. “Cinco Estrellas, campeón de campeones.” El Nuevo Diario, April 9, 2007.

16 Ibid.

17 Rondón, Tito. “Agustín Castro, CF.” La Prensa, February 7, 2002.

18 Miranda, Julio. “Cinco Estrellas, campeón de campeones.” El Nuevo Diario (Managua, Nicaragua), April 9, 2007. Note that the league was on hiatus in 1960-61 for financial reasons.

19 Nowlin, Bill. Mr. Red Sox: The Johnny Pesky Story. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2004: 183.

20 Lira, Miguel. “‘Cabo Mejía,’ un equipo de leyenda.’” El Nuevo Diario, August 21, 2006.

21 The other less famous honorees were Ventura Escalante (Dominican Republic), Daniel Herrera (Mexico), Adalberto Herrera (Venezuela), and Carlos Colas (Cuba).

22 One unconfirmed report said that his fatal illness was throat cancer (http://www.grupoese.com.ni/2002/11/18/etMMII1118.htm).

23 Baxter, Kevin. “Bonetto Plays Hardball in Nicaragua.” Los Angeles Times, August 24, 1989.

Full Name

Oliver Stanley Livingstone Cayasso Guerrero

Born

September 17, 1906 at Bluefields, (NIC)

Died

August 5, 1986 at , ()

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.