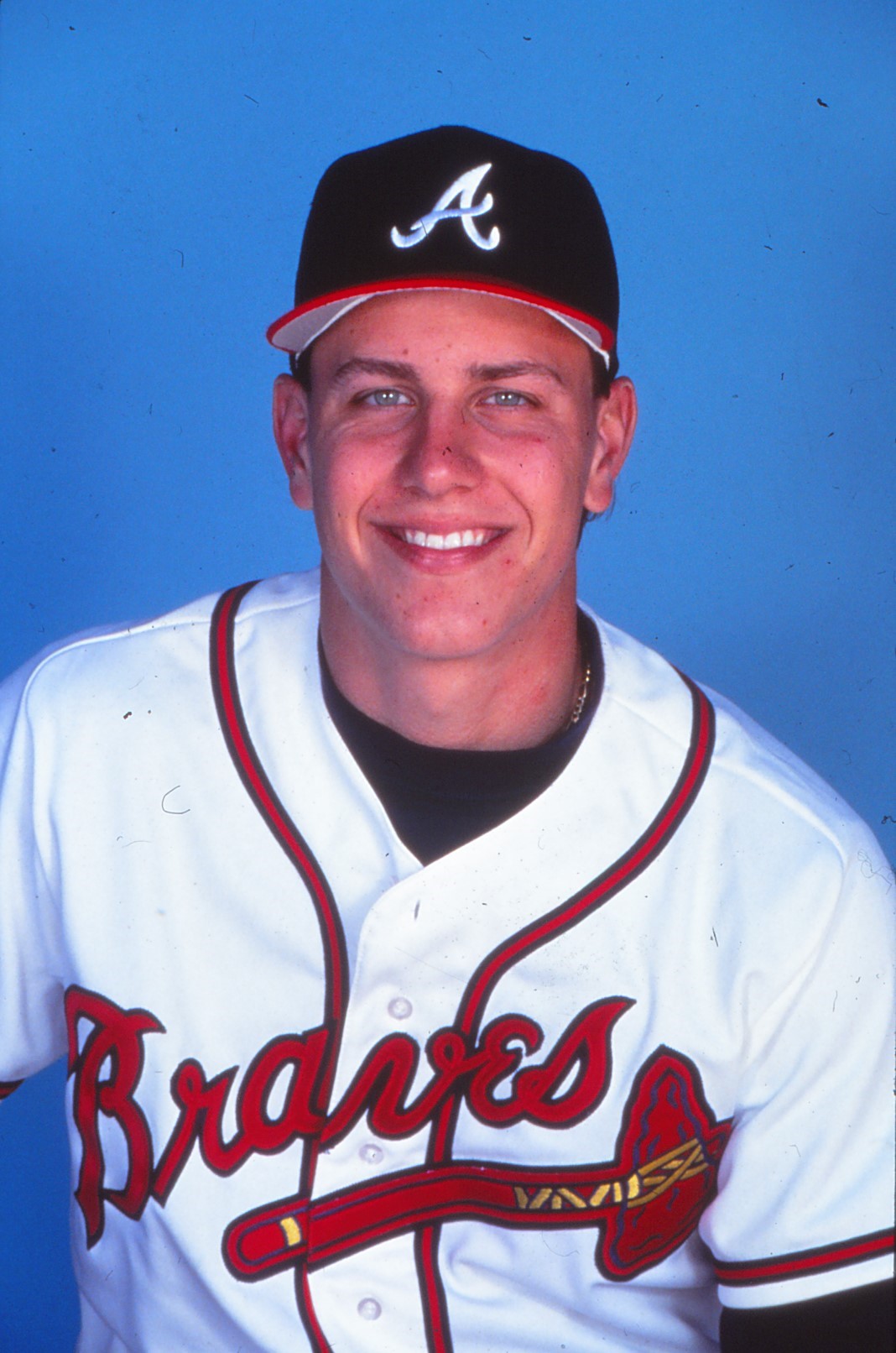

Steve Avery

In the early 1990s, no major-league pitcher’s nickname fit better than Steve Avery’s — The Kid. Unfortunately for Steve and the teams he played with, the trials, tribulations, and disappointments that sometimes come with adulthood came much too fast.

In the early 1990s, no major-league pitcher’s nickname fit better than Steve Avery’s — The Kid. Unfortunately for Steve and the teams he played with, the trials, tribulations, and disappointments that sometimes come with adulthood came much too fast.

Steven Thomas Avery was born in Trenton, Michigan, on April 14, 1970 to Kenneth W. and Constance “Connie” Marich Avery. Ken, a standout lefty pitcher from Michigan State, was signed by the Detroit Tigers to a contract with their Knoxville farm team in the summer of 1961, with orders to report to spring training the next season. Starting the year at Thomasville in the Georgia-Florida League, Ken posted a 6-2 record, earning him a promotion to Jamestown (NYP League), where he won nine more games, losing five. He and Connie were married that fall, and Ken returned to the mound the next year with the Duluth-Superior Dukes, in the Northern League. Ken fashioned a 13-4 record that season, on a mound staff that included future big leaguers Pete Craig, Pat Jarvis, Denny McLain, and Joe Sparma, as the Dukes won their pennant by 12 games. Rather than return to pro ball the next season, Ken decided to focus on family and a career outside of baseball, eventually retiring as athletic director of Taylor (Michigan) high schools. Ken and Connie Avery had four children — Ken Jr., Mike, Steve, and Jennifer.1

Steve had an outstanding prep career at Taylor’s John F. Kennedy High School, where he participated in basketball and cross-country, as well as baseball. When he was 16, Avery led his American Legion baseball team to the state championship, and was awarded the KiKi Cuyler Award as the tournament’s most valuable player.2 In his senior year at JFK, Avery went 13-0 on the mound, with 196 strikeouts and an 0.51 ERA in 88 innings. He batted.511, with 8 home runs and 44 RBIs.3

There was not much doubt that Avery would be an early selection in the 1988 amateur draft; the only question was how high he would go. The San Diego Padres, choosing first and seeking more immediate help, decided to go the college route, selecting pitcher Andy Benes from the University of Evansville. The Cleveland Indians, who chose second, had their eyes on Avery, but instead went for high-school shortstop Mark Lewis, from Hamilton, Ohio. Next in line were the Atlanta Braves, who jumped at the chance to draft Avery, hoping to lure him away from his scholarship offer from Stanford University.

The Braves had been doormats of the National League, having finished last or next to last each of the past five seasons. After a four-year managerial stint in Toronto, Bobby Cox had returned to Atlanta as the Braves’ general manager in October 1985. He set out to rebuild the farm system as the road back to respectability, rather than trying to remake the team at the major-league level with trades and free agents. Steve Avery was exactly the type pitcher the team thought it could build around.

After nearly a month of negotiations, Avery finally signed with the Braves on June 30, 1988, for a reported bonus of $211,500. That was significant, because it was the highest bonus ever paid to a high-school pitcher. That “record” stood for five weeks, until the Montreal Expos signed Reid Cornelius, their 11th-round draft pick, for $225,000.4

Avery was assigned to the Braves’ Appalachian (Rookie) League club in Pulaski, Virginia. After having his professional debut rained out the night before, he made his first appearance in the first game of a July 11 doubleheader against the Martinsville Phillies. The lefty pitched five innings, giving up four hits and a walk while striking out seven, to pick up the 5-0 victory. After the game, Pulaski manager Cloyd Boyer said, “I can see why they drafted him number one. He’s definitely a big-league prospect.” On the prospects of his club, Boyer continued, “I fully expect him to be with us the entire season, as all the rest of the players. Avery was sent here for me to work with. No longer than he’s been here, it’s obvious he’s hard-working, dedicated, and has a good attitude. And the Lord blessed him with great ability.”5 (Incidentally, eighth-round draft pick Mark Wohlers closed out the doubleheader by hurling a 3-2 complete-game three-hitter, giving the Braves a hint that the future might be bright, indeed.)

In his debut pro season, Avery posted a 7-1 record and a 1.50 ERA in 10 games, with 80 strikeouts and only 19 walks in 66 innings. He was named to the Appalachian League All-Star team at the conclusion of the season.

Based on his showing in Pulaski, Avery jumped to the Durham Bulls, the Braves’ high Class-A team in the Carolina League, for 1989. The team was loaded, with 10 players who would go on to see at least some major-league action, nine of them pitchers. The Bulls easily finished first in their division, but Avery wasn’t around to see the finish. Based on a 6-4 record with a 1.45 ERA and 90 strikeouts against 20 walks, he was promoted in midseason to the Double-A Greenville Braves. Avery didn’t miss a beat, going 6-3 in 13 starts. At age 19, he was the youngest player on the team, but had little trouble adjusting to his new surroundings.

Avery started the 1990 season at Richmond. He was only 20, and had reached Triple A much more quickly than anyone would have imagined. It was in Richmond that he first came under the guidance of pitching coach Leo Mazzone. “I didn’t teach Steve Avery a pitch,” said Mazzone. “He had them. So my job was to see that he kept them — and that worked out real well.”6 Avery’s record was only 5-5 through the first two months of the season, but he was showing maturity and confidence beyond his years. “In Steve’s case, he became a great pitcher at an early age because he trusted himself with a change of speeds,” said Mazzone. “He was a power pitcher out of high school, and had always been a strikeout pitcher. Most times it’s going to take a pitcher a long time to trust an offspeed pitch.”

Come early June, the Braves found themselves in familiar territory — last place, but won six of their first 12 games for the month, including a doubleheader in Cincinnati on June 12. Marty Clary had already been dropped from the rotation, and so was Derek Lilliquist, after being on the short end of a 23-8 shellacking at the hands of the San Francisco Giants on June 8. Yet even though help was obviously needed on the pitching staff, Braves fans were surprised when Avery was summoned from Richmond to start the June 13 game against the Reds. He was still the youngest player on the roster, and most assumed the Braves would like him to get a full season under his belt there. Getting called up after only 13 Triple-A games to join the big-league club would be enough to make any rookie excited enough to leave all of his luggage in the taxi when he got to the Braves hotel, as Avery did, but he would be facing a team in first place in the NL West.7

Avery’s nervousness may have lessened a bit when the Braves staked him to a 2-0 lead in the top of the first inning. He fared well in his initial major-league inning, allowing only a walk and a stolen base to Chris Sabo. Reality set in in the second, however, when the Reds tied the game at 2-2 on a leadoff triple by Glenn Braggs and singles by Todd Benzinger, Mariano Duncan, and Billy Hatcher. Things were no better in the third, when the Reds touched up Avery for two walks, a stolen base, three singles, and a double, driving him from the mound and taking a 6-2 lead. Reliever Marty Clary simply threw gasoline on the fire, allowing a wild pitch, two doubles, and a single without recording an out and leaving the game at 8-2.

Six days later, Avery again faced the Reds, this time in Atlanta, and fared a bit better. He pitched into the fifth inning, allowing only one run on six hits and two walks, leaving with the game tied 1-1.

Three days after Avery’s first appearance before the home crowd, changes were made that affected Atlanta’s baseball fortunes for the next two decades — Bobby Cox returned to the dugout as Braves manager (as well as keeping his general manager job, too), and he brought Leo Mazzone up from Richmond as his pitching coach. Cox decided to give The Kid a chance to stay in the rotation, and in Avery’s next start, on June 26, he went seven innings, beating the Los Angeles Dodgers, 4-2, for his first major-league win.

The rest of the 1990 season was pretty much a learning experience for Avery. He started 20 games and had one more in relief, finishing the season with a 3-11 record. His best game, by far, was on August 24 in Atlanta, when he fashioned his first major-league complete game and shutout, 3-0, over Greg Maddux and the Chicago Cubs. Maddux also pitched a complete game, and at the plate both hurlers had success. Avery touched up Maddux for two singles, and Greg recorded one against Steve.

For the team as a whole, it was a disappointing year, with the Braves finishing in the cellar for the third straight year. At the end of the season, the pitching staff included Tom Glavine, John Smoltz, Charlie Leibrandt, Kent Mercker, and Paul Marak. All except Leibrandt were less than 25 years old, and only Smoltz had a winning record in 1990. Some in the press were starting to call Atlanta’s staff the “Young Guns.” The Young Guns were starting to mature in 1990, but few seemed to notice.

When spring training started in 1991, the Braves had a new general manager, John Schuerholz, who had come after a successful 23-year stay in Kansas City. The move allowed Bobby Cox to relinquish the general manager part of his job, and to focus exclusively on the team on the field. Schuerholz recognized the maturing of the pitching staff, but knew that to be effective, he needed to improve the defense behind them. So he did, importing first baseman Sid Bream, third baseman Terry Pendleton, shortstop Rafael Belliard, and center fielder Otis Nixon.

The revamped team got off to an 8-10 record in April, not great, but much improved over the 4-13 mark in 1990. By the end of May, the won-lost record stood at 25-19, and the team was in second place, only a half-game behind the Los Angeles Dodgers. Fans were starting to notice that there was a difference in this team. The Braves stayed within three games of the Dodgers until near the end of August, when consecutive wins by Leibrandt, Glavine, Smoltz, and Avery moved the Braves into first place.

The Braves held on through September, to win the NL West crown by one game over the Dodgers. Glavine’s 20 wins garnered him the NL Cy Young Award at season’s end, Smoltz won 14 and Leibrandt 15, and Avery seemingly matured overnight, posting an 18-8 mark, good to place him sixth in the Cy Young voting. The Young Guns had come through, and led the “Worst to First” Braves to their first postseason action since 1982.

Avery had atoned for his woes with the Cincinnati Reds in 1990 by beating them 7-5 to give the Braves their first win of the 1991 season. Down the stretch in September, he hurled two complete-game victories over the Dodgers, 9-1 in Atlanta on September 15, and a 3-0 shutout in Los Angeles five days later. In his last win of the season, he took a no-hitter into the seventh inning against Houston, settling for a three-hitter in a 5-2 victory.

Going into the National League Championship Series against the Pirates, the Braves dropped the first game in Pittsburgh, and Avery then drew the starting assignment for Game Two. He responded by twirling 8⅓ shutout innings before turning the game over to Alejandro Peña, in an eventual 1-0 Braves victory. Six days later, back in Atlanta, Pittsburgh had taken a 3-2 series lead over the Braves, when Avery went back out for Game Six. Following almost the same script as in Game Two, he threw eight scoreless innings of three-hit ball, with Peña coming in for the final inning of the 1-0 game. John Smoltz’s 4-0 shutout the next night sent the Braves to their first World Series appearance since 1958. Avery’s two 1-0 shutout victories and 16⅓ scoreless innings earned him the MVP honors for the NLCS.

In the 1991 World Series, against the Minnesota Twins, Avery pitched into the eighth inning in Game Three, leaving with a 4-2 lead in a contest the Braves eventually won 5-4, and left Game Six behind 3-2 in a game the Braves tied but finally lost 4-3 in the 11th inning. He didn’t receive a decision in either game. The Braves ultimately lost the Series in an epic John Smoltz-Jack Morris pitching duel, which the Twins won 1-0 in 10 innings. Regardless of the outcome, Braves fans will never forget that magical “Worst to First” season!

Six days after the end of the World Series, Avery and Heather McMillan, his girlfriend since the seventh grade, were married. The ceremony was obviously planned well in advance, with a scheduling nod to the World Series — just in case. “It worked out,” said Avery. “I got to miss all the planning. I didn’t get stuck going to the shower and everything.”8

When spring training 1992 came around, the excitement of the previous season subsided a bit while attention was paid to the work at hand — how to repeat what had happened in 1992, and take the next big step: winning the World Series. The team got off to a slow start, and found itself in a fourth-place tie on Memorial Day, five games behind the San Francisco Giants. The Braves didn’t get back to the .500 level until June 7, and didn’t find their way into first place until July 22. From then on, there was no stopping the team, and they finished the season winning their second consecutive National League West title by eight games over the Cincinnati Reds.

As for Avery, in some ways his 1992 season was better than 1991 — he led the league in games started with 35, pitched 23⅓ more innings, and lowered his ERA from 3.38 to 3.20. His won-lost record fell to 11-11, however, primarily because the team had trouble scoring when he was on the mound. Six of his 11 losses were by two or fewer runs.

When the postseason came along, Avery returned to his old ways against the NL East champion Pirates by extending his NLCS shutout streak to 22⅔ innings in Game Two and picking up the win. Up three games to one, Avery took the mound in Game Five, hoping to punch the Braves’ ticket to the World Series. Nothing went as planned, and he experienced the worst start of his career, giving up four runs on a single and four doubles, while recording only one out, leading to a 7-1 Pirates victory. A 13-4 Pittsburgh blowout in Game Six brought on the decisive final game of the Series. Avery’s early departure from Game Five made him available for work in Game Seven, and he made his first relief appearance of the season in the bottom of the seventh inning. Entering the game with two outs and the bases loaded, Avery induced a long fly out by Andy Van Slyke to end the inning, and then held the Pirates scoreless in the eighth, maintaining a 2-0 Pittsburgh lead. That kept the game close enough to set the stage for the heroics by Pendleton, Justice, Bream, Gant, Berryhill, Hunter, and, finally, Francisco Cabrera’s bases-loaded two-run pinch-hit single in the bottom of the ninth, to send the Braves back to the World Series.

In the World Series against the Toronto Blue Jays, Avery pitched into the ninth inning of Game Three before giving up a leadoff single and leaving the game with the score tied 2-2. The trio of Mark Wohlers, Mike Stanton, and Jeff Reardon failed to get the job done, with Avery being charged with the 3-2 loss. In Game Six, he was pulled after the fourth inning, with the Blue Jays ahead 2-1. The Braves rallied to tie the game in the bottom of the ninth inning, but a two-run double by Dave Winfield in the top of the 11th put the Jays ahead 4-2, and they held on in the bottom of the inning to claim their first World Series ever. It was the Braves’ second consecutive Series loss.

During the offseason, the Braves signed free-agent pitcher Greg Maddux, just off a Cy Young Award-winning season with the Cubs. The 1992 Braves pitching staff had given up the fewest runs in the league, and adding Maddux to the rotation that included Glavine, Smoltz, and Avery would only cement the expectation that the team would return to the World Series for a third straight year. To the dismay of the rest of the league, the Braves had added yet another star to their “Young Guns” staff, a rotation that is now considered to have been one of the best in baseball history.

Avery started 1993 with high hopes, and he didn’t disappoint, posting the best year of his career to date. By the end of June, he sported a 9-2 record, with an eight-game winning streak, and was named to the National League All-Star team. He continued his fine work in the second half of the season, but ran into trouble on September 12 in San Diego. Leading 1-0 in the fourth inning, Avery suffered a muscle injury under his left (pitching) armpit, but kept pitching and gave up five runs on three hits, a walk, and an error before leaving the game. He pitched four more games in September, with two wins and a loss, to bring his season record to 18-4, with a 2.94 ERA.

The Braves won their division championship again in 1993, and took on the Philadelphia Phillies in the NLCS. Avery started Game One against the Phillies’ Curt Schilling, but left after the sixth inning behind 3-2. The Braves rallied to tie the game in the ninth inning, but lost 4-3 in 10 innings. In Game Five Avery and Schilling faced off again. This time, he pitched through the seventh inning, but was behind 2-0 when he was replaced by Kent Mercker. The Braves came back in the ninth inning again, this time scoring three runs to tie the game, but the Phillies scored on a Lenny Dykstra home run off Mark Wohlers in the 10th to take the game. Two days later, back in Philadelphia, the Phillies prevailed in Game Six, to dash the Braves’ hopes of a third straight World Series appearance.

The 1994 season opened with a cloud of uncertainty, with labor negotiations and the threat of a player strike having dragged through the winter. For the Averys, their lives were upheaved with the sudden and unexpected death of Heather’s father, James McMillan, on March 29,9 and the premature birth of Heather and Steve’s first child, Evan Thomas, 12 days later. Evan was born nearly three months early, and weighed only 2 pounds, 13 ounces. “The doctors are amazed at how well he’s doing,” said Avery. “We’re still worried, but now it’s a different kind of worry. Before, we didn’t even know if he was going to be born. At least now I can see him. That makes it a little easier.”10

Evan stayed in the hospital until late July and underwent nine surgeries during his first year. Unbeknownst to the general public, Avery was a commuting pitcher for virtually the entire 1994 season. He made several trips back to Michigan during spring training, and after the season started, he flew back home after every start, rejoining the team in time for his next game.

“You could tell he was tense,” said teammate John Smoltz. At times he had a shorter fuse, not as patient, because it was a continual roller-coaster. It was a difficult time, and we all felt for him.”11

On the mound, Avery posted an 8-3 record, although the Braves actually won 15 of his 24 starts. His ERA jumped from 2.94 in 1993 to 4.04, even though his hits allowed per nine innings dropped and his strikeout total (122 compared with 125) was down by only three in about 72⅔ fewer innings compared with 1993. Through it all, Avery didn’t miss a single start in 1994, but sometimes showed a lack of control — he walked 12 more batters in the abbreviated season than he did in all of 1993. Some thought he was just tired from the rigors of the season, but others wondered if he was concealing an injury, perhaps a carryover from his muscle injury the previous September.

When the strike eventually started on August 12, it cast a shadow over major-league baseball, but it couldn’t have come at a better time for the Averys, letting them be together when Evan came home from the hospital.

Few remember that because the labor strike was not settled until April 2, the 1995 season opening was delayed until April 26. An abbreviated 144-game schedule was implemented, and the Braves started well, winning seven of their first eight games. The only loss in that span was a 9-1 drubbing by the Dodgers in Los Angeles. The loss was charged to Avery, who left the game after retiring only one out of five batters in the fourth, behind 3-0. After their first eight games, however, the team lost eight of their next 10, and didn’t get back to first place until a July 4 win against the Dodgers.

Other than a 4-0 complete-game shutout against the Florida Marlins on May 19, Avery showed little of his previous dominance during the first half of the season. By August 1, he had pitched into the seventh inning in only nine of his 17 starts, and his 4.21 ERA at that point was his highest since his rookie season. He failed to find consistency through the rest of the season, dealing with mechanical issues and loss of confidence, and he ended the campaign with a 7-13 record.

Regardless, the Braves again led their division, and returned to the NLDS against the Colorado Rockies. Manager Bobby Cox decided to go with only three starters — Maddux, Glavine, and Smoltz, and took the series three games to one. Avery made only one appearance, in relief of Tom Glavine in the second game, and gave up a run while retiring only two batters.

In the NLCS against the Cincinnati Reds, Tom Glavine started Game One, and left after the seventh inning trailing 1-0. After the game was turned over to Alejandro Peña, the Braves tied the game in the ninth and took the lead in the 10th. Mark Wohlers worked the ninth and 10th for the Braves, and Brad Clontz took over in the 11th to protect the lead, but could record only one out before manager Cox called on Avery, who walked the only batter he faced. Thankfully, for the Braves, Greg McMichael came in and put out the fire, preserving the win.

After winning the first three games against the Reds, Cox made a very unpopular decision, in the fans’ eyes. He decided to start Avery in Game Four, despite the fact that in two postseason relief outings he had retired only two batters. Perhaps Cox thought that since the Braves were already up three games to none, Avery might be able to give the other starters a bit of a rest. Whatever his thinking, he had to be pleased. The old Steve Avery showed up, pitched six innings of two-hit shutout ball, struck out six Reds, and was the winning pitcher as the Braves completed a four-game sweep of Cincinnati and headed back to the World Series. After two years of struggling, Avery felt he was back where he belonged.

Moving on to the World Series against Cleveland, the starters were rested and Maddux and Glavine each eked out one-run victories in the first two games. Smoltz was knocked around in Game Three and lasted less than three innings, but the Braves rebounded and the game went to overtime, the Indians pulling out a 7-6 win in 11 innings.

Come Game Four, manager Cox had no apprehension about giving the ball to Avery, and the lefty rewarded his trust with another six innings of three-hit, one-run baseball. The Braves won the game, 5-2, and moved to within one game of the championship.

What Avery remembered most about the game was that Bobby Cox gave him the ball when no one else wanted him to have it. “I pretty much stunk all year,” said Avery. “He said, ‘Ave, I’ve got confidence in you,’ and that was it.”12

Cleveland won Game Five, 5-4, and the Series moved back to Atlanta, where in Game Six Tom Glavine’s eight innings of one-hit ball and Dave Justice’s home run brought the Atlanta Braves their first World Series title.

Avery started out the 1996 season well, reaching the seventh inning in nine of his first 12 starts, and he sported a 6-4 record by the end of May. As the season progressed, however, ineffectiveness set in and he lost a bit of velocity on his fastball. He missed nearly two months due to injury near the end of the season, and he finished the season with only a 7-10 record.

The Braves reached the World Series again in 1996, this time against the New York Yankees. Avery’s only appearance in the Series was in Game Four, when the Braves blew a 6-0 lead and eventually lost the game, 8-6. That game is remembered as the one where Mark Wohlers gave up a game-tying three-run home run to Yankees catcher Jim Leyritz, but Avery was actually the losing pitcher in that contest. Replacing Wohlers to start the 10th inning, Avery allowed a single and three walks in two-thirds of an inning, the last walk, to Wade Boggs, forcing in the go-ahead run. The Braves had entered that game having won two out of the first three games, but the Yankees then won this contest and the next two to claim their first championship since 1978.

In late October the Braves granted Steve Avery free agency. He had been through the highest of highs and the lowest of lows in his nine seasons in the Braves organization, and he is always mentioned when discussion comes up about his Hall of Fame rotation mates Tom Glavine, Greg Maddux, and John Smoltz. There are many in the Braves organization who think Avery was on the path to the Hall of Fame as well had injuries not taken their toll. He came up to the majors when the Braves had little pitching at all, and he left the Braves not because he really wanted to, but because the team now had too much talent for him to stay around.

Hoping that a change of scenery would help, Avery signed a one-year contract with the Boston Red Sox in January 1997. There, he was reunited with former Braves third-base coach Jimy Williams, who had just come over from Atlanta to replace Kevin Kennedy as the Red Sox manager. Williams was hoping Avery would benefit from the opportunity, and besides, he needed someone to fill the rotation vacancy created when Roger Clemens left Boston to sign with the Toronto Blue Jays.

Avery won two of his first four starts in Boston, but lost most of May and all of June to injury, and finished with only a 6-7 record for the season. He returned to the Red Sox for the 1998 season and pitched with a modicum of success, pitching to a 10-7 record, his first winning season since 1994. But he was still plagued by injuries that just weren’t getting any better, and the Red Sox released Avery in October.

Hoping there was still a bit of magic left in Avery — after all, he was still just 29 years old — the Cincinnati Reds signed him in December, in an effort to bolster their staff. He added a bit, but not much, to the Reds’ second-place finish in 1999, duplicating his 6-7 record with the Red Sox two years previously, but his season came to an end in late July, when he underwent season-ending surgery to repair a torn labrum. The Reds released him at the end of the season.

Avery tried to come back in 2000, signing with his original club, the Braves, in January. There was nothing the Braves would have liked more than for a healthy Steve Avery to be able to come back. Avery spent the season shuttling between the Braves’ top four farm teams — Richmond, Greenville, Myrtle Beach, and Macon. He won 4 and lost 12 games in his minor-league stay, but the Braves weren’t concerned about results, they just wanted to let him get his strength back and be healthy. Avery returned to spring training with the Braves in 2001, but things did not improve to the point where he would be able to pitch, and he was released just before the start of the season.

For a couple of years, Braves scouting director Paul Snyder tried to get Avery to come back with the club as a minor-league pitching coach, but he wasn’t interested. “I understood that, he was home and had small children that he wanted to be with. But I still wanted him, he was smart, he had had successes and failures that he could relate to with young pitchers. I think he would have made a terrific coach,” said Snyder.13

In late 2002, Avery started giving serious thought to making a comeback. He had gone two seasons without pitching, had continued his workouts, and was in shape. Also, 8-year-old Evan knew more about baseball now, but didn’t remember ever seeing his dad pitch. Avery told his hometown Detroit Tigers he’d like to give it a try. On January 23, 2003, the Tigers signed him to a minor-league contract and invited him to spring training. Tigers manager Alan Trammell said that Avery was a long shot to make the team, but that he wasn’t ruling it out.14

Avery was sent to Detroit’s Toledo farm team at the end of spring training, but showed enough there that he was called up to the big-league club on May 9. He made his Tigers debut in Tampa Bay on May 11, when he entered the eighth inning with the Tigers leading the Devil Rays, 8-2. He gave up a leadoff single to Carl Crawford, who was erased on a double play, and Avery completed the inning unscathed. He made his home debut against the Oakland A’s three days later when he came on with the score tied, the bases loaded, and two outs in the ninth inning. Avery struck out the only batter he faced, Scott Hatteberg, and picked up his first victory in almost four years when the Tigers rallied in the bottom of the ninth for the win. He recorded another relief win on May 26, and in all made 19 relief appearances for the Tigers before being sent back down on July 26. Only five of his 19 outings were in Tigers victories, which doesn’t necessarily speak ill of Avery’s performance — the team finished with a 43-119 record!

Avery finished with a 2-0 record for the Tigers, but an ERA of 5.63. He recorded only six strikeouts in 16 innings of work, a testament to his fastball no longer being effective.

Avery retired with a 96-83 major-league won-lost record, an All-Star Game appearance, an NLCS MVP award, three National League Championship rings, and one World Series trophy. His star rose quickly, shone brilliantly, but faded much too fast with injuries.

Said John Smoltz: “I’ll give Steve credit, he came back and fulfilled the dream that every player has — playing for the home team. I grew up around Detroit and signed with the Tigers, but never got to play for them. Steve did. Tommy (Glavine) would love to have played for the Red Sox. He never got a chance, but Steve and I did. He was lucky in that way.”15

As of 2020 Steve and Heather Avery lived in Dearborn, Michigan. Steve was inducted into the Taylor Sports Hall of Fame in 2004, and the baseball and softball fields at John F. Kennedy High School in Taylor are named for him. He coached the Detroit Bees Perfect Game 14U team to the Battle of Great Lakes championship in 2019. Evan pitched on the Adrian College baseball team. In 2020 he was an account executive in group and hospitality sales with the Braves. Daughter Emma Grace, born just after the close of the 1997 season, was a second-grade teacher in Detroit, and son Owen, born after Steve’s career ended, was in high school.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and the online archives via Newspaper.com, NewspaperARCHIVE.com, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 The author’s parents, Dean and Helen Hufford, served as a host family for Pulaski Braves players in the 1980s. Steve lived with them during his 1988 rookie season. Mrs. Hufford and Steve’s mother, Connie, have maintained a correspondence of more than 30 years, and much of the family information in this biography is taken from Mrs. Avery’s letters.

2 “Steve Avery — Inducted in 2004.” ci.taylor.mi.us/605/Steve-Avery.

3 Allen Simpson, ed., Baseball America’s Ultimate Draft Book 2016 (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 2016), 350.

4 Simpson.

5 Tom Hawley, “Braves Take Twinbill, Avery Pitches Shutout,” Southwest Times (Pulaski, Virginia), July 12, 1988: 6.

6 Leo Mazzone and Scott Freeman, Leo Mazzone’s Tales From the Mound (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2006), 15.

7 bravesgeneralstore.com/brief-and-brilliant-steve-averys-time-in-atlanta-2/.

8 Steve Rushin, “Game Boy,” Sports Illustrated, February 17, 1992.

9 Detroit News, April 1, 2004. genealogybank.com/doc/obituaries/obit/13BF267243875200-13BF267243875200.

10 Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, April 13, 1994: 25.

11 Robes Patton, “Load Has Lightened for Avery as Son’s Health Has Improved,” South Florida Sun-Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale), April 22, 1995. sun-sentinel.com/news/fl-xpm-1995-04-22-9504214013-story.html#.

12 Steve Hummer, “Bobby Cox — The Players’ Manager,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 29, 2010. ajc.com/sports/baseball/bobby-cox-the-players-manager/PdPc1Xf5vWf43F2t2mSBWN/.

13 Paul Snyder, telephone conversation with the author, January 10, 2020.

14 Sunday Advocate (Baton Rouge, Louisiana), February 16, 2003: 16C.

15 John Smoltz, personal conversation with the author, November 2014.

Full Name

Steven Thomas Avery

Born

April 14, 1970 at Trenton, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.