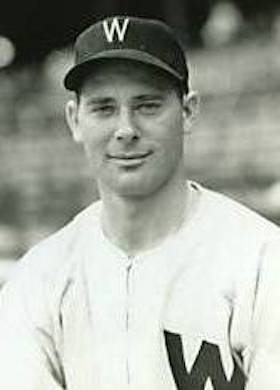

Steve Sundra

Entering the last day of the 1939 season New York Yankees’ righty Steve Sundra owned an unblemished 11-0 record, but a September 30 home run from Boston Red Sox rookie Ted Williams spoiled that. From 1900-60 Sundra’s .917 winning percentage ranked fifth among pitchers with 10 or more decisions in a single season. Combined with three additional victories tacked on from 1938, his 14 consecutive wins fell two shy of an American League record, but it ranked right alongside Hall of Famer Whitey Ford as a Yankees record through 2000.

Entering the last day of the 1939 season New York Yankees’ righty Steve Sundra owned an unblemished 11-0 record, but a September 30 home run from Boston Red Sox rookie Ted Williams spoiled that. From 1900-60 Sundra’s .917 winning percentage ranked fifth among pitchers with 10 or more decisions in a single season. Combined with three additional victories tacked on from 1938, his 14 consecutive wins fell two shy of an American League record, but it ranked right alongside Hall of Famer Whitey Ford as a Yankees record through 2000.

In 1944, Sundra was called into the service during World War II after having moved on to the St. Louis Browns. Two years later he returned to the club only to be released after just two homely appearances. Sundra brought suit against the Browns under the GI Bill, but it was denied by a federal judge. Within a year he contracted cancer. “[B]uilt like a steel rail,”1 the strapping 6’2”, 190 pound player shriveled to a mere 75 pounds when the disease eventually claimed him in 1952, only four days before his 42nd birthday.

Steven Richard Sundra was born on March 27, 1910, one of 10 children of Michael and Marie (Kalata) Sundra in Luxor, Pennsylvania, 35 miles east of Pittsburgh. His parents were Czechoslovakian immigrants who arrived in the United States around the turn of the 20th century. Michael entered the coal mines of western Pennsylvania before moving his family to Cleveland, Ohio, around 1926. Each of his sons appears to have gravitated to baseball beginning with one of the eldest, John.2 Manager of the semi-pro Holecek Meat squad, John recruited his 17-year-old brother Steven in 1927. The youngster started in the outfield before discovering success on the hill and soon became the pitching protégé of former minor league catcher Carl Schlee. The advanced training helped Sundra lead the Fisher Foods club to the 1931 National Baseball Federation championship, chalking up three wins over a Cincinnati entry, twice by shutouts. NBF official Frank “Dolk” Novarlo, a semi-pro manager and professional scout, alerted Cleveland Indians’ general manager Billy Evans to the tournament’s pitching sensation, and Evans signed Sundra that fall.

Despite posting mediocre-to-average numbers in the minor leagues from 1932-34, Sundra’s fastball (heat that earned him the nickname “Smokey”) and sinker from a three-quarters side-arm delivery stoked the envy of other franchises. “[B]ecause of his natural equipment [Sundra] is regarded as a sure bet,”3 said The Sporting News in 1935, while Milwaukee Brewers manager Allan Sothoron called him the “best prospect in the [American Association].”4 In Cleveland’s 1935 spring training Sundra put up a fierce fight with reserve outfielder Ab Wright for the final roster spot. Sundra lost. Reassigned to the American Association, he was attached to the Minneapolis Millers’ bullpen where he struggled with a near league-worst 6.18 ERA. On August 15, in what appears to have been a trial arrangement, the Millers sent Sundra to the Yankees AAA affiliate in Newark, New Jersey.

Shuffled into the Bears’ rotation, Sundra delivered a seven-hit shutout against the Syracuse Chiefs on August 29, and went himself one better eight days later by a four-hit whitewashing of the Albany Senators. His brief stay with the Bears was near flawless—5-1, 1.47 with five complete games in 55 innings—marred only by an incident in which the generally quiet hurler “kicked the wadding out of his manager, Bob Shawkey.”5 (Details of the scuffle appear to be lost forever to history.) On December 11 the Yankees finalized the trial arrangement by sending their contentious righty Johnny Allen to the Indians for Sundra and fellow-pitcher Monte Pearson. Retired Yankee slugger Babe Ruth disapproved. Manager Joe McCarthy “traded away his best right-hander and his pennant chances in the deal,” he said.6 But Yankees’ owner Jacob Ruppert had a far different take: “Sundra [was] the man we wanted all the time. [St. Paul Saints’ owner] Bob Connery had tipped us off that Sundra had more stuff than any pitcher in the minor leagues.”7

Despite the lavish praise, Sundra would not earn a permanent spot on the Yankee roster for three more years. On April 17, 1936, he made his major league debut at home against the Boston Red Sox, yielding two walks and two hits over two innings in a mop-up situation. Twenty-four days later, without making another appearance, Sundra was optioned to Newark when rosters were cut to the required 23-player limit. Once again Sundra blossomed in a longer stint—29 games, 26 starts—with a circuit leading 2.84 ERA, setting the stage for the following season.

Strongly favored by McCarthy, Sundra sported Yankee pinstripes on Opening Day 1937, but exactly one week later—April 27—he was returned to Newark before making an appearance. With a roster that included slugger Charlie Keller and future HOF second baseman Joe Gordon, the 1937 Bears won the International League pennant by a vast 25½ games and, nearly 80 years later, are still considered one of the greatest teams in the history of the minor leagues.8 Sundra’s contributions to this effort were hardly middling. Though he fell short of a consecutive ERA title, Sundra’s 3.09 placed among the league leaders along with 15 wins and 1.249 WHIP. But the Bears would go on to capture the Junior World Series without Sundra; on September 1 he was admitted to a Newark hospital for an emergency appendectomy.

Sundra was out of options in 1938. Despite his sore arm that developed in March, the Yankees were forced to retain him or risk losing him on waivers. On May 5, more than two weeks into the season, Sundra made his first major league start and, after a sloppy 7⅓ innings yielding eight runs, he collected with his first big league win in a 12-10 slugfest over the Browns. Used as a reliever and spot starter thereafter, Sundra struggled to a 9.28 ERA in June and was placed on waivers. Strong interest from other teams, including a particularly aggressive pursuit from the Chicago White Sox, caused the Yankees to rethink their strategy and hold onto Sundra. On July 27, he garnered his second win, helping his own cause with his first major league home run, a game-winning shot off Browns righty Fred Johnson. Sundra also enjoyed a sweet September, going 3-0, with a 2.51 ERA in his last five outings (two starts).

A mere four days separated the 1939 Yankees from joining their 1927 Murderers Row brethren as the only clubs to accomplish a wire-to-wire first place run (a feat later achieved by the 1984 Detroit Tigers and 2001 Seattle Mariners). The well-balanced Bombers attained this success with a major league best 967 runs and a circuit best 3.31 ERA. A club record-setting 14 game win streak and a 2.76 ERA from Sundra contributed substantially to this feat. He was virtually untouchable from May 24 through August posting a 6-0, 1.01 mark in 16 appearances. On July 4, the Yankees lost the first game of a doubleheader. Between games Lou Gehrig delivered his famous farewell speech. After his 277-word delivery, the future HOF first baseman spied Sundra in the clubhouse and said, “Big Steve, win the second game for me, will ya?”9 Sundra did. He delivered a six-hit complete game 11-1 victory over the Washington Senators for the dying gentleman. Seven weeks later Sundra tossed his first career shutout, a four-hit blanking of the Browns. His compelling finish garnered strong consideration for a World Series starting assignment behind Yankee greats Red Ruffing and Lefty Gomez. Though McCarthy eventually opted for other starters, Sundra appeared in Game 4 of the Fall Classic, surrendering three unearned Cincinnati runs in 2⅔ innings. In October Sundra drew an honorary mention in the voting for AL Most Valuable Player. Two months later while he was a spectator in a Cleveland court,the judge recognized him. “Are you the fellow who caused the Indians so much trouble?” the magistrate asked. “If I had the power, I’d set you down for the whole season.”10 (Sundra bedeviled the Indians throughout his career, posting a career-best 2.52 ERA with nine wins in 10 decisions.)

Events were not as rosy for either the righty or the Yankees as a whole in 1940. Excluding the war years of 1944-45, the Yankees fell to their second lowest winning percentage in 37 years as the club’s batting average collapsed to a league worst .259. Sundra struggled from the first, yielding a hitter-friendly 59 hits and 18 walks in his first 38 innings (0-5, 8.53). Rumored to be demoted to the American Association’s Kansas City Blues after he suffered losses to the Browns on consecutive days. Future HOF backstop Bill Dickey saved his season. He began working with the righty on spotting his pitches, and on August 9, with Ruffing injured for the third time, Sundra yielded just one hit over 6 2/3 innings against the Philadelphia Athletics to earn his first win of the season. He collected two more wins in August and finished with a record of 4-6, 5.53 ERA in 99⅓ innings.

His late turnaround couldn’t keep him on the team, though. With the Yankees expecting the emergence of youngsters Norm Branch, Steve Peek, and Charley Stanceu, Sundra became expendable. On March 27, 1941, after spurning interest from the Red Sox, Tigers and Indians (the Yankees were reportedly uninterested in trading him to a likely contender), Sundra was sold to the perennial second-division Senators for an estimated $10,000. Slotted as the club’s fourth starter, Sundra established himself as the potential staff ace with a record of 4-1 and 3.83 ERA a month into the season (the combined record of the four other starters through May 17 was 8-13, 5.03). But from here Sundra plummeted. On May 24, he was chased in the first inning after yielding six runs to the A’s, and then he went on to lose six of his final seven decisions. “Despite all his stuff . . . ,” opined famed Washington Post sports writer Shirley Povich, “[Sundra] tips off his delivery by exposing the ball during his windup.”11 Sundra finished with a disappointing record of 5-12, 5.75 ERA in his last 23 appearances (18 starts).

The offseason acquisition of much-travelled hurler Bobo Newsom combined with the emergence of future HOF righty Early Wynn spelled Sundra’s rapid exit from Washington. On June 7, 1942, after just six appearances, he and outfielder Mike Chartak12 were traded to the Browns for pitcher Bill Trotter and popular St. Louis outfielder Roy Cullenbine. Sundra’s inclusion was the deal-maker: “I liked Sundra ever since he had that 11-and-one record with the Yankees in 1939,” explained Browns’ GM Bill DeWitt. “[I] felt if he had more work he should develop into a consistent winner.”13 Under the tutelage of skipper Luke Sewell, who had a knack for pitcher-reclamation projects, Sundra yielded dividend. On July 5 he threw a complete game win over the White Sox while coming within a single shy of a cycle at the plate. (A decent hitter, Sundra collected another hit in unique fashion on September 13: ducking away from an inside pitch, the ball hit his bat and sailed over the third base bag).14 His next victory on July 17 helped the Brownies to their longest winning streak in 22 years. Sundra finished the season with three complete game wins including a four-hit gem against the Tigers in September 8 before a paltry 723 paying fans (one of the smallest crowds in the history of Detroit’s Briggs Stadium). The strong finish helped launch one of Sundra’s finest major league seasons.

Evidence for his glorious 1943 appeared from the start. A successful romp in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, where spring training was held due to wartime travel restrictions, spawned a record of 2-1, 2.42 in Sundra’s first four outings— which attracted trade interest from Philadelphia skipper Connie Mack. Resentful for having been sold by New York in 1941, Sundra took particular satisfaction in besting his former teammates. On July 21, he held the Yankees scoreless for 9⅓ innings in an extra-inning 1-0 win, followed three weeks later by a one-hit gem. Still a year removed from pennant contention, the Browns never seemed able to muster any offense with Sundra on the mound. In nearly a third of his 29 starts, his teammates scored two runs or fewer. Still he placed among the league leaders in wins and shutouts, posting single-season career highs in appearances (32), games started (29), complete games (13), shutouts (3) and innings pitched (208). Registering a winning percentage more than 100 points higher than the Browns did as a team, Sundra again earned honorary mention in the AL Most Valuable Player selection.

Seemingly on his way to his greatest season ever, Sundra opened the 1944 season with two complete game wins, including a three-hit victory over the Tigers, to lead the Browns to an AL season-opening record nine straight wins. On May 2 his ERA stood at a brisk 1.42. But Sundra was living on borrowed time. In the early spring he had passed a military exam in Camden, New Jersey, and on May 9 the US Army beckoned. Initially assigned to Camp Sibert in Gadsden, Alabama—where varied celebrities including Mickey Rooney and Red Skelton served their time as well15—Sundra played alongside other major leaguers on the self-styled Sibert’s Gashouse Gang. Stationed in Virginia the next year, Sundra played in a spring exhibition benefitting the war bond effort. First serving in the army transportation corps (involving four trips to the British West Indies16), the 35-year-old worked primarily during the war as a physical instructor for much younger recruits. At some point during this training Sundra injured both knees, injuries destined to doom the rest of his career.

In February 1946, Sundra was discharged from the army at Fort Meade, Maryland, and quickly reunited with his former club. Unable to pivot properly on his damaged knees, Sundra’s delivery of the ball regressed. During a west coast swing through San Francisco and Hollywood in March two Pacific Coast League teams roughed him up. And on May 28, in just his second appearance of the season, the White Sox tagged him for five runs (two earned) on four hits and three walks. Unceremoniously, the next day he was given his unconditional release, and he returned to his adopted home in Atlantic City, New Jersey, to his family of four.

In 1939, Sundra had met New Jersey native and former Miss Atlantic City runner-up Edythe Blanche Werner in the Big Apple while she was visiting the New York City World’s Fair with her family. The couple married during the July 1940 All Star break. The union ended in divorce in 1947 but produced two athletically inclined sons. In 1963-64 the eldest, Steven, Jr., pitched in the Yankees’ farm system before launching a successful business career, while Joseph pitched for Penn State University during his freshman and sophomore years before dedicating himself to his studies; he later served as an electrical engineer for the Apollo space program at Cape Canaveral, Florida from 1967-72.

Off-seasons during his career Sundra worked in construction related jobs and, in 1943-44 before being drafted, as a steamfitter at a Coast Guard station in Atlantic City. Returning to construction work following his release, Sundra filed suit against the Browns on October 15, 1947 seeking $5,413.40 in back pay17 under the GI Bill (likely inspired by the successful 1946 filing by Al Niemiec against the PCL’s Seattle Rainiers18). Citing Sundra’s injured knees, the Browns claimed they had met their obligations: “Our understanding of the law was that the returning veterans had to be able to perform their duties in order to be re-employed and we gave Sundra ample opportunity, and he wasn’t able to perform.”19 As the case carried into 1949, veterans organizations and former teammates lined up in support of Sundra. They included then-St. Louis Cardinals’ minor league manager Al Hollingsworth, who was denied permission to leave the Class B Allentown, Pennsylvania club to testify in federal court in Missouri. On December 14, 1949, Judge Roy W. Harper denied Sundra’s claim for back pay.

Within months of the ruling, Sundra found himself engaged in a life-or-death struggle. In March 1950, he fell ill and was later diagnosed with cancer of the rectum. An avid sportsman, Sundra was once the picture of health. He enjoyed hunting, fishing and golf, and was also a great football fan, travelling nationwide during the 1939 offseason to varied professional and collegiate matches. During his Yankee years, the New York press considered Sundra the strongest player on the squad—a remarkable distinction among musclemen such as George Selkirk and Charlie Keller. Scribes were also amazed at his ability to consume massive meals without ever gaining an ounce of fat. But cancer eventually ate this fine specimen of a man down to 75 pounds. To help defray Sundra’s crippling medical costs, donations poured in from the Association of Professional Ball Players of America and the Yankees. On March 1, 1952, the proceeds from an Atlantic City high school basketball game were donated to Sundra. Five days later he chartered a plane to Cleveland to spend his remaining days with his father. On March 23, 1952, he died and was buried in Cleveland’s Calvary Cemetery.

Plucked from the Cleveland sandlots, Sundra compiled a record of 56-41, 4.17 ERA in 859⅓ innings over nine major league seasons. With flashes of brilliance lurking in an average résumé when he was called away to war, he returned damaged, a mere shadow of his former self, and was abruptly ushered out of the game—a sad outcome for a returning veteran, made sadder still by his premature death.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Rod Nelson, chair of the SABR Scouts Committee and Tom Schott for review and edit of the narrative.

Sources

Websites

Ancestry.com

Steven and Joseph Sundra, telephone interviews, March 7 & 8, 2016, respectively

Notes

1 “Three and One: Looking them over with J.G. Taylor Spink,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1940: 4.

2 In 1947 Steven’s younger brother Edward launched a minor league career that spanned six seasons, interrupted only to attend to his dying brother’s care.

3 “Another Forest City Acorn,” The Sporting News, January 10, 1935: 1.

4 “Holland Gives Millers New Home Run Threat,” ibid., May 9: 3.

5 “Caught in the Crowded Lobbies of Chicago at Major Confabs,” ibid., December 19: 7.

6 “No. 1 Hurler with the No. 1 Club,” ibid., June 25, 1936: 1.

7 “Sunnyboy Sundra’s Back on Beam,” ibid., May 4, 1944: 3.

8 Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright, “Top 100 Teams: 1937 Newark Bears,” Accessed March 9, 2016, http://www.milb.com/milb/history/top100.jsp?idx=3

9 “Pages Out of the Past,” Atlantic City Evening Union, January 18, 1952.

10 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, December 28, 1939: 9.

11 “Looping the Loops,” ibid., March 12, 1942: 7.

12 The lives of Sundra and Chartak were closely (and in one instance tragically) intertwined. After leaving the Yankees in separate transactions they were teamed together in Washington and St. Louis. Both men died at a young age from disease.

13 “Sunshine Ray for Browns in Sundra’s Card,” The Sporting News, November 4, 1943: 14.

14 Listed as a right-handed hitter, there is some evidence that Sundra briefly experimented with switch-hitting during a portion of his career.

15 Mike Goodson, “Camp Sibert hosted many legends,” July 24, 2011. Accessed March 17, 2016, http://www.gadsdentimes.com/article/20110724/NEWS/110729969

16 Gary Bedingfield, “Baseball in Wartime,” September 3, 2008. Accessed March 17, 2016, http://www.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/sundra_steve.htm

17 The amount represented the difference between what Sundra had been paid and his $8,000 salary in 1946.

18 Jeff Obermeyer, “Disposable Heroes: Returning World War II Veteran Al Niemiec Takes on Organized Baseball,” Baseball Research Journal, Volume 39, Issue 1 (Cleveland, Ohio: Society for American Baseball Research, Summer 2010). Accessed March 17, 2016, http://sabr.org/research/disposable-heroes-returning-world-war-ii-veteran-al-niemiec-takes-organized-baseball

19 “Browns Explain Sundra Release,” The Sporting News, April 9, 1947: 23.

Full Name

Steven Richard Sundra

Born

March 27, 1910 at Luxor, PA (USA)

Died

March 23, 1952 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.