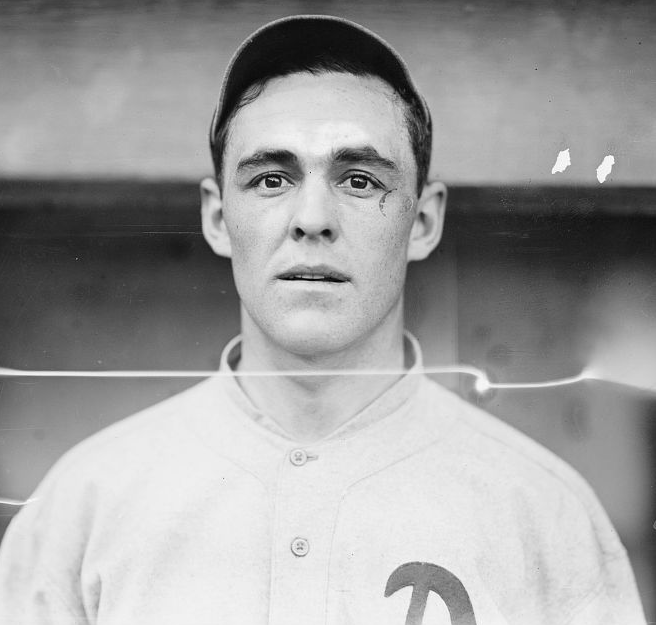

Stuffy McInnis

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…” During his 18-year career in the Major Leagues, John Phalen “Stuffy” McInnis’ teams finished in first place six times, winning five World Series, and in last place four times. He started his career by becoming the youngest member of Connie Mack’s famed “$100,000 infield,” replacing veteran Harry Davis at first base for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1911, and joining Eddie Collins, Frank (soon to be “Home Run”) Baker, and Jack Barry in that fabled infield. Following the dismantling of the Athletics after the 1914 season, Stuffy stayed on, suffering through three straight last-place A’s finishes. But whether it was feast or famine for his teams, McInnis remained a consistent singles hitter, an outstanding defensive first baseman, and a savvy clubhouse leader. A spry 5’ 9 ½” right-handed line-drive pull hitter with a boyish face, McInnis has a career batting average over .300, having amassed more than 2,400 hits. However, he is best known as one of baseball’s best defensive first basemen, due to his amazing consistency covering first base.

The fourth of five sons of Stephen and Udavilla (Grady) McInnis, Stuffy was born September 19, 1890 in the fishing town of Gloucester, Massachusetts. His father provided a good living for the family variously as a caretaker of a stable of driving horses, a chauffeur, and a “call” fireman for the Colonel Allen Hook and Ladder, No. 1. All McInnis’ brothers played baseball, but Stuffy stood out from an early age. He gained his unique nickname during his boyhood playing days, when teammates and spectators would shout, “That’s the stuff, kid, that’s the stuff!” after he had made a good play.

Playing shortstop, McInnis led Gloucester High School to championships in 1906 and 1907. In the summers of 1907 and 1908, he played for the Beverly, Massachusetts amateur baseball club. In July 1908, he joined the Haverhill Hustlers professional baseball club, and “soon became the sensation of the New England League,” according to the Philadelphia Athletics’ 1910 Championship Season Souvenir Program. He was paid $100 per month by the Hustlers, batting .301 in 186 at-bats under the tutelage of the legendary Billy Hamilton. On the advice of Dick Madden of the Beverly amateur club – who acted as a scout for the Athletics – McInnis was signed by A’s owner-manager Connie Mack at the end of 1908.

Stuffy’s slight stature and boyish looks were the cause of some confusion in his earlier years. Once, before a New England League game, umpire Steve Mahoney asked Hamilton when he was going to get his mascot off the field, pointing at McInnis. “Mascot nothing!” snapped Hamilton, “That’s my shortstop and he’s one of the best you’ve ever seen.”

In 1909, just 18 years old, McInnis was considered a potential rival for the starting shortstop position over Jack Barry, who had joined the major leagues just a year earlier. He stuck with the Athletics out of spring training, but ended up playing only 14 games – all at shortstop — in this first season. His major league debut on April 12 was an auspicious occasion for another reason, the grand opening of Shibe Park, the first steel and girder ballpark in the country. Jack Barry was injured, so Stuffy started in front of over 30,000 fans, a huge crowd for that era. Stuffy acquitted himself well, making an error but getting a hit as the Athletics defeated the Red Sox, 8-1, behind Eddie Plank. Stuffy finished the season with only a .239 batting average, but made himself useful off the bench, as he became particularly astute at stealing signs from opponents.

In 1910, McInnis played at shortstop, second base, third base, and even in the outfield, batting .301 in 38 games. It was during this season that Connie Mack told Stuffy to start working out at first base, despite his short stature and lack of experience at the position. Ben Houser, who was trying to become the A’s regular first baseman, tried to run McInnis off first every time he tried to take groundballs or throws. But in 1911 Mack kept Stuffy and released Houser who had hit only .188.

Before the 1911 season, Mack determined that McInnis would supplant regular first baseman Harry Davis, whose production had declined considerably in the previous year. However, when, early in the season, Jack Barry became sick, McInnis took over at shortstop instead. He played 24 games at shortstop, keeping Barry on the bench even some time after he recovered, due to his hot hitting. Eventually, Barry reclaimed shortstop, and McInnis took over first base from Davis.

On September 23, 1911, Connie Mack included McInnis’ name on the list of the 21 players eligible to represent the A’s in the World Series. However, two days later, Stuffy sustained an injury to his right wrist when he was struck by pitch from the Tigers’ George Mullin. Though no bones were broken, McInnis’ right forearm became badly swollen, and he was unable to throw even from first base to the pitcher’s mound with any speed or accuracy. McInnis did not play the rest of the season. In 126 games in 1911, Stuffy hit for a .321 batting average.

The Athletics won the 1911 American League pennant, limping into the World Series with the aged Davis replacing Stuffy at first base. It was the second year in a row that McInnis’ team played in the World Series without Stuffy taking a meaningful part in the outcome. However, with the Athletics up 13-2 with two outs in the ninth inning, and a 3-2 series lead, Mack put Stuffy into the game defensively at first base, so that Stuffy could say he’d played in a World Series. A’s pitcher Chief Bender promptly induced Giants catcher Artie Wilson to ground weakly to Frank Baker at third base. The Series ended as Stuffy touched the ball for the first time, nabbing Baker’s throw for the final putout. For Stuffy, it was the first of five World Series with three different teams.

McInnis entered the 1912 season surrounded by great expectations and with huge shoes to fill. Harry Davis, despite his declining performance over the previous two seasons, had been one of the American League’s premier power hitters, and the A’s regular first baseman since Mack formed the team in 1901. McInnis responded to the expectations with an excellent season, batting in 101 runs, the fourth most in the league, and scoring another 83 in the effort, while batting for a .327 average. However, for the first time in three years, the Athletics failed to win the American League pennant.

In 1913, the A’s got back on track, winning the American League pennant for the third time since McInnis joined the team. During the season, McInnis batted for a .324 average, with 90 runs batted in, which tied for second in the league. His defense also improved dramatically, providing a glimpse of his future defensive greatness. In the World Series, the Athletics beat the New York Giants in five games for the World Championship. McInnis slumped badly at the plate in the Series, garnering only two hits in 17 at-bats for a paltry .118 batting average.

McInnis had another strong offensive year in 1914, finishing with a .314 batting average, including 95 runs batted in, second most in the league. The Athletics again won the American League pennant. They entered the 1914 World Series as heavy favorites over the Boston Braves. The Athletics managed only a lackluster offensive performance, scoring six runs in the improbable four-game sweep by the “Miracle Braves.” Stuffy again struggled at the plate in the Series, going 2-for-14 for a .143 average. The entire A’s team hit only a lackluster .172 for the four games.

Nineteen fourteen had begun with the defection of outfielder Danny Murphy, a team member since 1902, to the newly-formed rival Federal League. While the loss of Murphy, no longer a regular player, did not greatly weaken the Athletics in 1914, it was the harbinger for what was to be the end of the Philadelphia Athletics’ first dynasty. Philadelphia entered the 1915 season after losing starting pitchers Chief Bender and Eddie Plank to the Federal League, third baseman Baker to a rebellious one-year retirement, and second baseman Eddie Collins, in a sale by Mack, to the Chicago White Sox. The result was that they had no hope of winning even half their games, let alone competing for the pennant. To make matters worse, in July, Mack sold Barry’s contract to the Boston Red Sox, thus leaving McInnis as the sole remaining member of the Athletics’ once-feared infield. Although McInnis, too, was wooed by the Feds, he reportedly opted to stay with the Athletics out of loyalty to Connie Mack, even for considerably less money.

Not surprisingly, however, McInnis’ next three years with the Athletics were unhappy ones as the A’s finished in the cellar in 1915, 1916, and 1917. Stuffy, however, continued to be productive, batting .314, .295, and .303 in those years to remain one of baseball’s premier first basemen.

Stuffy had an interesting encounter with future teammate Babe Ruth early in the 1916 season. McInnis was walking across the lobby of the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia on an April evening when he saw Babe Ruth relaxing in an easy chair. That afternoon Ruth had defeated the Athletics in Shibe Park and allowed only five hits, including one by McInnis. McInnis walked over to the Babe and said, “You pitched a fine game out there today, Babe. That fastball of yours was really hopping all afternoon.”

McInnis later reported that although he had batted against Ruth many times in the past, the Babe looked him squarely in the eye and said, “Yeah, kid, it was a pretty good game. Glad you could get out to the ballpark and see it.”

After the end of the 1917 season, Mack demanded that McInnis take a salary cut. When McInnis refused, Mack traded him to the Boston Red Sox in January 1918 for third baseman Larry Gardner, outfielder Tilly Walker, and backup catcher Hick Cady.

After nine years with the Athletics, McInnis helped lead his new team to the war-shortened 1918 American League pennant. The Red Sox won the World Series four games to two primarily on the pitching of Babe Ruth and Carl Mays, but also with the timely hitting of McInnis and a few teammates. In the first game, McInnis singled home the only run of the game in the fourth inning as Babe Ruth shut out the Cubs, 1-0. In Game Three, Stuffy singled in the fourth and scored the deciding run on a squeeze bunt by Everett Scott in a 2-1 Red Sox victory. For the Series McInnis batted .250, well above the team’s lowly .186 average. He also fielded his position flawlessly. For example, in Game Four he took part in three double plays and made the pivotal defensive play of the game in the ninth inning, forcing Fred Merkle at third base on Chuck Wortman’s little tapper in front of the plate.

Boston’s fortunes fell in 1919, 1920, and 1921, as first Mays and then Ruth were traded. The team finished in the bottom half of the American League each season, as McInnis again found himself on a team that had been dismantled for cash by its owner. McInnis hit for averages of .305, .297, and .307 in the three years, respectively.

It was during this period that McInnis honed his first base defense to a point of near-infallibility. In 1919, he made seven errors in 118 games for a .995 fielding average. In 1920, he again made seven errors, this time in 148 games, for a league-leading .996 fielding average. In 1921, McInnis made only one error in 152 games for a record .9993 fielding average.

Even that single error was debatable. It occurred on May 31st in Fenway Park against the Athletics. Jimmy Dykes was leading off first and the Red Sox catcher fired to McInnis on an attempted pick-off play. Stuffy dropped the ball on the tag and the official scorer charged him with an error. The next season, Dykes, knowing that was the only error McInnis committed all year, would bring the play up whenever he got to first base against the Red Sox. He would say, “You know, Stuffy, that really wasn’t an error. I was safe either way, whether you dropped it or not.”

According to Dykes, Stuffy would purse his lips and make believe that he was not listening. Finally, during a game when he brought up the play once again, McInnis said out of the corner of his mouth without looking at him, “Shut up, Dykes. You just shut up about it. If you mention that error one more time, so help me, Dykes, so help me… “

Even with that single bobble in late May, Stuffy’s 1,300 chances accepted without an error in 1921 set the record for errorless chances in a season. Further, from May 31, 1921 to June 2, 1922, McInnis went 163 games and 1,625 chances without making an error at first base.

According to one report, Stuffy disputed the error that brought an end to his errorless streak, a wide throw that he believed should have been charged to the thrower. McInnis reportedly bumped into the sportswriter who had served as the official scorer on the train afterward and, after a brief discussion, socked him in the nose. The story may be apocryphal as Stuffy was generally considered one of the true gentlemen in the game.

Stuffy did not drink or smoke and was “careful” in his speech. But he was proud of his fielding prowess. On June 23, 1919 McInnis was charged with his first error of that season after 526 chances when he could not handle a low throw from his old Athletics’ teammate, Jack Barry, who was playing as a part-time second baseman. Some 30 years later McInnis was coaching baseball at Harvard and Barry was the coach at Holy Cross. According to one of Stuffy’s former players, whenever Harvard played Holy Cross, the two old teammates would meet at home plate before the game to present their lineups and their greeting never varied: “How are you, Stuffy?” Barry would say. “Good. How are you, Jack?” Stuffy would reply, “You know that was a low throw, don’t you, Jack.”

There is evidence that McInnis was well aware of his batting average as well. In an interview late in his life Smoky Joe Wood related that McInnis would approach him at the tail end of a season if the game didn’t mean anything in the standings and say, “Look, it doesn’t matter to you, let me get a hit or two and I’ll get picked off or caught stealing.” According to Wood, if McInnis got a hit, he would keep his end of the bargain and make an out on the bases. Wood made it clear that Stuffy never bet or took advantage but was just trying to pump his batting average up a little at the end of the year.

Before the 1922 season, McInnis was traded to the Cleveland Indians. He hit for a .305 batting average, making only five errors in 140 games. Cleveland finished fourth in the American League. After the season, McInnis was released on waivers. He signed with the Boston Braves, with whom he spent two seasons, batting .315 and .291 in 1923 and 1924, respectively. The Braves finished at or near the bottom of the National League in both seasons, and released McInnis in April 1925. After the 1924 season, however, Stuffy had toured Europe as part of John McGraw’s White Sox — Giants exhibition series. While there he met with British royalty, partook of an audience with the Pope, and visited Monte Carlo.

McInnis ultimately signed with the Pittsburgh Pirates for 1925. Playing in only 59 games, he hit for a .368 average, with a .437 on-base percentage and a .484 slugging average. Stuffy’s veteran leadership was instrumental in helping the young Pirates win the National League pennant. In the World Series against the Washington Senators, the Pirates lost three of the first four games. John McGraw, whose Giants had lost to the Senators the previous year, suggested to Pirates manager Bill McKechnie that he play McInnis at first base instead of the struggling George Grantham, to take advantage of Stuffy’s World Series experience. McKechnie took McGraw’s advice and the Pirates won three straight to come back for an improbable World Series win. McInnis’ steadying hand and timely hitting were major contributors to the Pirates comeback. McInnis played part-time for the Pirates again in 1926. He hit for a .299 average, but recorded only 127 at-bats in 47 games. The Pirates finished third in the National League.

In 1927, McInnis returned to Philadelphia as manager of the Phillies. Despite some early-season heroics by the perpetually woeful “Flying Phils,” the team lost 103 games and ended up in its usual spot at the bottom of the National League. In 1928, Stuffy served as player-manager of the Salem Witches in the New England League. The 38-year old batted .339 in part-time duty. He went on to coach baseball at Norwich University, Cornell and Harvard. After six seasons of coaching Harvard, McInnis resigned in 1954 because of failing health.

In his private life, McInnis was as steady as he was on the ball field. He married Elsie Dow in 1918. They had one daughter, Eileen, and three grandchildren. For the last 40 years of his life, McGinnis lived at 11 Tappan Street in Manchester-by-the Sea, Massachusetts, a few miles down Cape Ann from his native Gloucester. On February 16, 1960, after a lengthy illness, McInnis passed away in Ipswich, Massachusetts. He was 69 years old and had been preceded in death the previous year by his wife Elsie.

Although known for his fielding wizardry, McInnis was an outstanding hitter as well. For his 18-year big league career, he batted .308 and hit over .300 14 times. He was known as a consummate contact hitter, striking out only 189 times in about 8,200 career at-bats. For three years of his career, he struck out fewer than 10 times in over 500 plate appearances. Only Joe Sewell has ever topped that feat. In 1922, Stuffy struck out only five times in 550 at-bats. In 1924, he whiffed only six times in almost 600 at-bats. On April 29, 1911, Stuffy went five-for-five, all singles, against the New York Highlanders’ Hippo Vaughn and Jack Quinn while seeing only seven pitches. He hit the first pitch he saw for a single three times and the second pitch twice.

Typical of Deadball Era players, McInnis did not hit many home runs – only 21 for his career – and many were inside-the-park jobs, including two in one game on August 12, 1912 versus Vean Gregg of the Cleveland Naps. His most memorable home run, however, came on June 27, 1911 in a game at Huntington Avenue Grounds in Boston. McInnis stepped to the plate to lead off the seventh inning while the Red Sox were still warming up between innings. With Eddie Collins of the A’s still on the field talking to Red Sox center-fielder Tris Speaker, Stuffy hit a warm-up pitch by Ed Karger into short center field, which the Boston outfielders were not in a position to field. McInnis circled the bases for an inside-the-park home run against the unprepared Red Sox. The umpire upheld the homer and on appeal, American League president Ban Johnson refused to overturn the umpire’s ruling or the Athletics victory, based on a new, soon-to-be-withdrawn, rule prohibiting warm-up pitches between innings. Johnson had implemented the rule due to concern that some games were taking over two hours to play!

While McInnis was an excellent hitter, it was as a fielder that he truly left a legacy. He was one of the earliest first basemen to excel at catching throws one-handed and he did so in a way that appeared natural and not flashy, as was often the case with his contemporary Hal Chase. His one-handed style enabled him to reach for high and wide throws, and helped him overcome the disadvantage of his rather short stature. He is also credited as the inventor of the “knee reach,” during which maneuver he performed a full, ground-level split in stretching for a throw. According to one report, he was also the first to wear the claw-type first baseman’s glove to improve his efficiency in scooping balls out of the dirt.

With his fielding prowess, his lifetime batting average of .307 in 18 major league seasons, his participation in five World Series, and his membership in the best infield of the Deadball Era, Stuffy McInnis is certainly worthy of consideration for Baseball’s Hall of Fame. One thing is for certain: in his long career he lived up to his childhood nickname.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “When Boston Still Had the Babe: The 1918 World Series Champion Red Sox” (SABR, 2018), edited by Bill Nowlin. It originally appeared in SABR’s “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006).

Sources

The Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1969)

Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia (Sport Media Publishing, Inc., 2003)

Baseball Hall of Fame Library clippings file on Stuffy McInnis

Douskey, Franz, “Smoky Joe Wood’s Last Interview”, National Pastime, No. 27, p. 69 (2007)

Garland, Joe, “‘That’s the Stuff!’ They Said . . . “, North Shore Magazine, March 4, 1972, p. 3.

Honig, Donald, The Greatest First Basemen of All Time (New York: Crown Publishers, 1988)

Karst, Gene & Jones, Martin J. Jr., Who’s Who in Professional Baseball (New York: Arlington House Publishers 1973)

Lieb, Frederick G., The Boston Red Sox (New York: G.P. Putman & Sons 1947, republished Carbondale & Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003)

Lieb, Frederick G., Connie Mack — the Grand Old Man of Baseball (New York: G.P. Putnam & Sons, 1945)

McInnis, Stuffy, “My Fifth World’s Series”, Baseball Magazine, Oct. 1918 at p.470.

Murphy, Jeremiah V., “The Tale of Stuffy McInnis’ 1921 Error”, Boston Globe, Feb. 21, 1993, at p.2 North Weekly

Philadelphia Athletics 1910 Championship Season Souvenir Program, as excerpted by the Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society at philadelphiaathletics.org

Parsons, Roy, “Stuffy is Gone, but His Legend Will Live Forever”, Gloucester Daily Times, Feb. 17, 1960, p. 1.

Porter, David L. ed, Biographical Dictionary of American Sports (New York: Greenwood Press 1987)

Romanowski, Jerome G., The Mackmen (self-published 1979)

Shatzkin, Mike, ed., The Ballplayers (New York: William Morrow & Co. 1990)

Smith, Ira L., Baseball’s Famous First Basemen (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co. 1956)

Stang, Mark, Athletics Album — A Photo History of the Philadelphia Athletics (Wilmington, Ohio: Orange Frazer Press 2006)

Total Baseball, Seventh Edition

Washington Post, March 10, 1912

Waterman, Ty, and Springer, Mel, The Year the Red Sox Won the World Series (Boston: Northeastern Univ. Press, 1999)

www.baseballlibrary.com/baseballlibrary/ballplayers/M/McInnis_Stuffy.stm

Full Name

John Phalen McInnis

Born

September 19, 1890 at Gloucester, MA (US)

Died

February 16, 1960 at Ipswich, MA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.