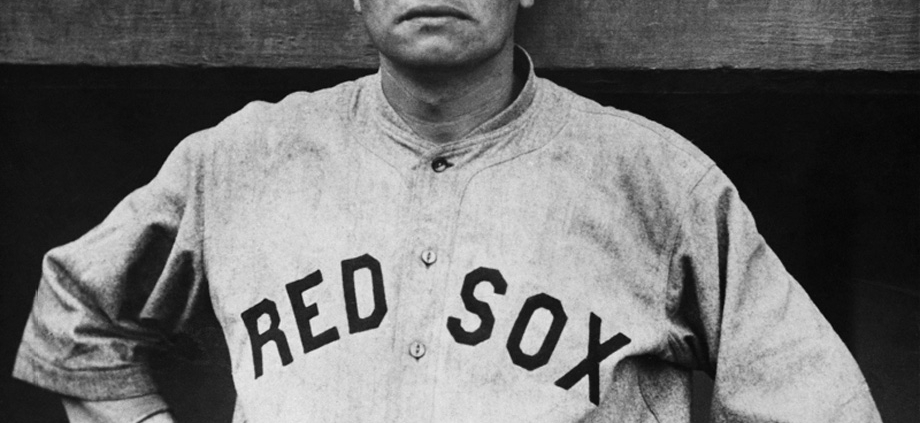

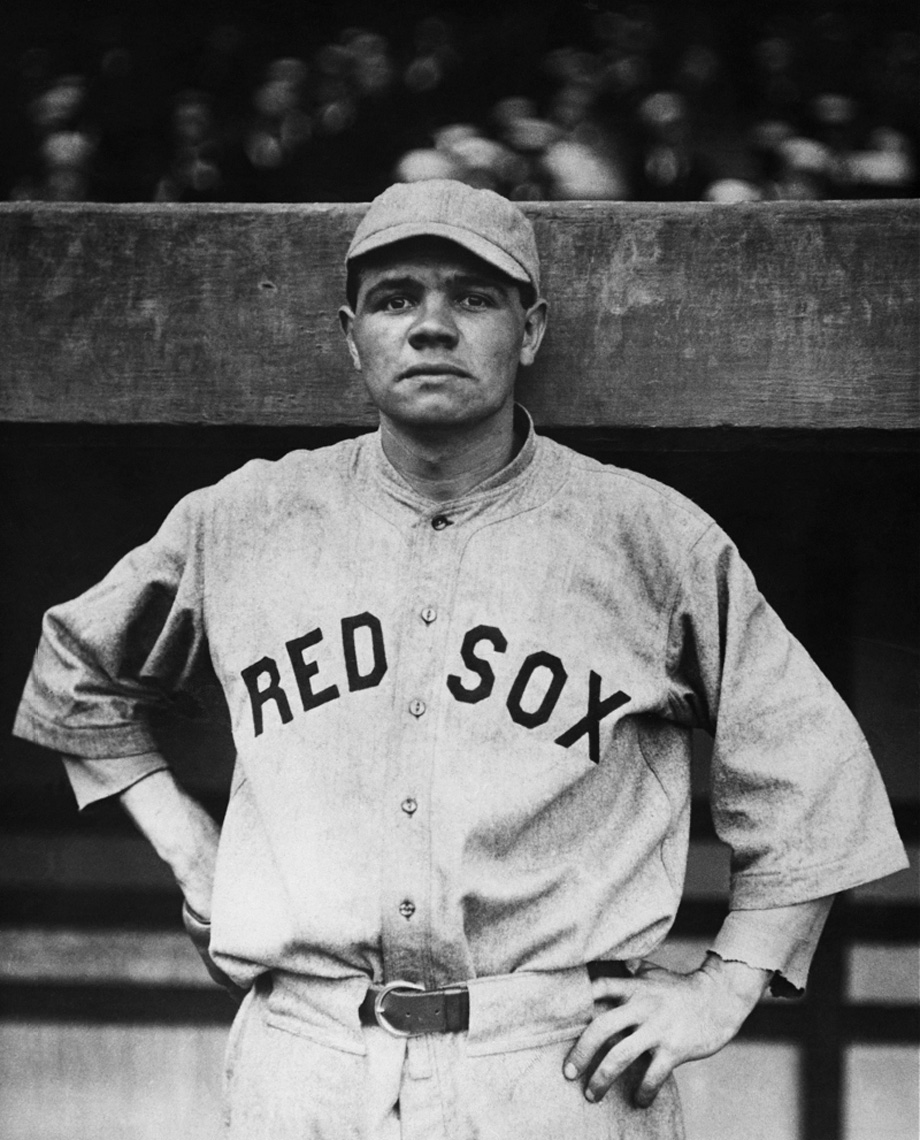

September 9, 1918: Babe Ruth finally gets his first base hit in a World Series game

Through the first three games of the 1918 World Series, the Boston Red Sox had scored a total of just four runs – but won two of the three. After those games in Chicago, the Cubs and Red Sox took the same Sunday train back to Boston to resume play.1

Through the first three games of the 1918 World Series, the Boston Red Sox had scored a total of just four runs – but won two of the three. After those games in Chicago, the Cubs and Red Sox took the same Sunday train back to Boston to resume play.1

Game One winner Babe Ruth, although working with an “iodine-painted finger” on his throwing hand thanks to an injury incurred during the train ride, was manager Ed Barrow’s choice to start Game Four for the Red Sox.2 He’d thrown a 1-0 shutout in that first game. Lefty Tyler, who had won Game Two for the Cubs, was manager Fred Mitchell’s choice.

Ruth’s injury “bothered him constantly, causing the ball to shine and sail,” and may have been reflected in the six walks and seven base hits off Ruth during the course of the game.3 The St. Louis Post-Dispatch agreed: “The cut bothered him considerably.”4

Max Flack led off the game, singling to right field for Chicago. Charlie Hollocher lined out to Everett Scott at short. Red Sox catcher Sam Agnew fired the ball to Stuffy McInnis at first and picked off Flack. Les Mann fouled out to first base.

The Cubs got to Ruth for two singles in the second to put two runners on with two outs, but Bill Killefer grounded into a shortstop-to-third force play.

Tyler walked to lead off the third inning, but Flack forced him at second. Hollocher moved Flack to second on a grounder that McInnis handled by himself at first, and then Ruth picked off Flack – who was “caught napping” for the second time in three innings – by wheeling and throwing to Scott.5

Boston’s Dave Shean hit a one-out double to left field in the bottom of the first but was the only Red Sox player to reach base off Tyler in any of the first three innings.

Ruth retired the three batters he faced in the top of the fourth.

Shean led off in the Boston fourth, and Tyler walked him. Amos Strunk couldn’t execute the sacrifice and then flied out. Shean saw an opportunity and stole second base without drawing a throw, as the ball got a bit away from catcher Killefer. George Whiteman walked. McInnis hit back to Tyler, who had time to throw out the lead runner at third.

With two outs, Babe Ruth was up, batting sixth in the order. Ruth had led both leagues in home runs with 11 and batted an even .300. “The Tarzan of the Boston tribe” strode to the plate “swinging his savage looking black bludgeon.”6 But Ruth had accumulated 10 at-bats in three World Series (1915, 1916, and this one) and had yet to hit safely. Rather than walk the bases loaded, Mitchell decided to pitch to him.

Tyler tried to get Ruth to swing at outside pitches and didn’t give him much to hit, missing with the first three pitches. He appeared to walk him on an outside pitch at 3-and-1, but the umpire called it a strike. Knowing what he planned to throw next, Tyler twice tried to reposition Flack deeper in right, but Flack held his position.

On a 3-and-2 count, Ruth drove a fastball into deep right field. It was a triple over Flack’s head and almost to the center-field bleachers, driving in both Whiteman and McInnis. Ruth himself might have scored but for Tyler backing up the wide-of-the-bag throw to third base. Scott flied out to center to close the inning. The Red Sox had a 2-0 lead.

Charlie Pick singled to lead off the Cubs fifth and Tyler walked to lead off the sixth, but Ruth got Killefer to hit into a double play in the fifth and induced three successive grounders in the sixth.7

Tyler retired all six Boston batters.

In the seventh, with one out, Ruth walked Fred Merkle and pinch-hitter Rollie Zeider (batting for Pick), but a second pinch-hitter, Bob O’Farrell, grounded into a 6-4-3 double play.

Stuffy McInnis singled in the Red Sox seventh, and Ruth bunted him to second. Scott reached on a fielder’s choice – but McInnis was out at third – and Fred Thomas popped up to second base.

Ruth seemed to tire in the eighth. He walked Killefer, then allowed pinch-hitter Claude Hendrix to single to left field. Hendrix was a pitcher, but not a bad choice to bat; he’d belted nine extra-base hits (three home runs, three triples, and three doubles) and batted .264 during the regular season. With runners on first and second, Ruth threw a wild pitch and there were two men in scoring position with nobody out. Throughout the game, the Globe noted, Ruth was “ever on the brink of danger.”8

Max Flack was having a tough game and it only got worse when he grounded out to first baseman McInnis, who looked Killefer back to the bag at third while tagging out the oncoming Flack. Mitchell made his fifth substitution of the game after he saw that Hendrix seemed a little shaky on the basepaths (he almost got caught off second base); rookie Bill McCabe ran for Hendrix, who was already primed to pitch. Mitchell had Phil Douglas start warming up; he’d been 10-9 with a 2.13 ERA during the regular season.

Hollocher grounded out to second baseman Shean, whose only play was to first base; Killefer scored. Les Mann singled to left, scoring McCabe from third base. The game was tied, 2-2.

Ruth’s World Series scoreless innings streak was thus snapped at 29⅔. He’d surpassed the previous record (Christy Mathewson, with 28) and established a new record that stood for decades until Whitey Ford upped the ante by pitching 33 consecutive scoreless innings in the 1960, 1961, and 1962 World Series. Dode Paskert grounded out to end the eighth.

In a tied ballgame and facing a right-handed pitcher for the first time in the entire Series (Mitchell brought in the big righty Douglas), the Red Sox countered by having switch-hitter Wally Schang bat left-handed in place of Agnew. Agnew was 0-for-7 and hadn’t gotten on base yet in the three games he’d played. Schang came through with a single to center field – and then took second base when Killefer allowed another ball to get away from him for a passed ball.

Harry Hooper tried to bunt Schang to third base – and more than succeeded. Douglas pounced on the ball but threw it away – “Phil’s fatal fling.”9 Schang scored on the misplay and Hooper wound up on second base. Douglas then retired the next three batters and Hooper stayed on second throughout. But the damage was done. It was Boston 3, Chicago 2.

Schang took over behind the plate for Boston in the ninth. Manager Ed Barrow waited it out while Ruth got in trouble again, as Merkle singled into center field and Zeider walked. Finally he’d seen enough and brought in Bullet Joe Bush to relieve Ruth. Rather than head to the showers, though, Ruth took over for Whiteman in left field.

Chuck Wortman, who’d come into the game to play second for the Cubs in the seventh inning, bunted toward first base – but McInnis had anticipated well and played in daringly close, cutting off the ball before Bush could get to it. His boldness worked and McInnis fired across the diamond to Thomas, who got Merkle at third base. It wasn’t even close.

Turner Barber pinch-hit for Killefer and grounded into a 6-4-3 double play to end the game and secure the win for Ruth and the Red Sox. Boston held a 3-1 lead in the World Series and hoped to wrap things up the next day.

All the newspapers understandably saw Douglas’s throw as the tipping point in the game; the New York Times in particular suggested that his spitball was still wet when he fired an “impetuous, violent” throw toward first base: The “wet, slippery sphere skidded in his hand as he threw and went hopping to the right field stand.”10

The Chicago Tribune said that Mitchell “had been compelled to throw in so many reserves that he weakened his defense and the substitutes were unable to hold what ground had been gained.”11

Ruth hadn’t pitched all that well, with six bases on balls mixed in with seven hits and the wild pitch (and no strikeouts), while the Red Sox had only four hits in the game. But the Red Sox infield defense had been error-free and turned three double plays, including a couple of crucial ones in the seventh and ninth. McInnis was credited for digging at least a couple of tough throws out of the dirt, and Scott handled 11 chances at short without an error.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org, and drew substantially on Bill Nowlin and Jim Prime, The Boston Red Sox World Series Encyclopedia (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2008).

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BOS/BOS191809090.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1918/B09090BOS1918.htm

Notes

1 The First World War was in progress – the reason the Series was being played in September – and everyone realized that attendance would be down and revenues reduced. But the players had a written agreement and the teams weren’t living up to it. The players talked on the train and demanded a hearing before the National Commission. There was some talk of holding out and not playing. August Herrmann of the National Commission succeeded in deferring the discussion until after Game Four at Fenway Park. See a brief explanation by Allan Wood, “The 1918 World Series; Boston Red Sox – Chicago Cubs,” Bill Nowlin, ed., When Boston Still Had the Babe – The 1918 World Champion Red Sox (Phoenix: SABR, 2018), 211, 212.

2 Edward F. Martin, “Wonderful Support When Base Wobbles,” Boston Globe, September 10, 1918: 1.

3 The injury came from what was apparently some good-natured roughhousing with fellow pitcher Walt Kinney on the train from Chicago. Leigh Montville, The Big Bam (New York: Doubleday, 2009), 77. See Edward F. Martin and other contemporary sources, though the St. Louis Post-Dispatch (not necessarily a contradiction) said that Ruth had “lost his balance while walking down an aisle on the train, Sunday night, and put his hand through a window.” “Ruth Pitched Game with a Bad Hand: Mitchell Napping on Wortman’s Bunt,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 10, 1918: 16.

4 Ruth Pitched Game with a Bad Hand.”

5 “Ruth Helps Red Sox to Drive Within One Victory of World’s Baseball Title,” New York Times, September 10, 1918: 10.

6 “Ruth Helps Red Sox to Drive Within One Victory of World’s Baseball Title.”

7 Shean made a heads-up play in the sixth. With Tyler on base, Flack bounced one to Ruth, who threw badly to second. The ball got away from Scott. Allan Wood tells it well: “Shean, however, was positioned only a few feet behind the base. He was on his knees when he gloved Ruth’s errant toss, then crawled on his stomach in the dirt, tagging the bag with his mitt just ahead of Tyler’s foot.” Allan Wood, “The 1918 World Series; Boston Red Sox – Chicago Cubs.”

8 Edward F. Martin, Boston Globe.

9 Dick Jemison, “Red Sox Need Only One More Win,” Atlanta Constitution, September 10, 1918: 16.

10 “Ruth Helps Red Sox to Drive Within One Victory of World’s Baseball Title.”

11 I.E. Sanborn, “Triple Ruth Makes Good,” Chicago Tribune, September 10, 1918: 10. Mitchell used 16 players in the game.

Additional Stats

Boston Red Sox 3

Chicago Cubs 2

Game 4, WS

Fenway Park

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.