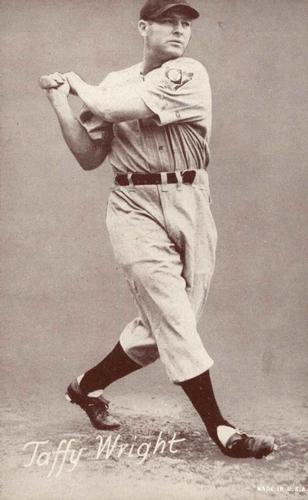

Taft Wright

“I’m sure God never meant me to be a ball player,” Taft Wright said. “If he had, I wouldn’t be built so close to the ground and always worrying about my weight and being muscle bound.”1

“I’m sure God never meant me to be a ball player,” Taft Wright said. “If he had, I wouldn’t be built so close to the ground and always worrying about my weight and being muscle bound.”1

Sportswriters called him “Fat Wright” and “Round Man.”2 Wright was a born designated hitter — born decades too soon. He was a left-handed line-drive hitter who walked more than twice as often as he struck out in most seasons, with enough power to produce doubles and triples, but he cracked double figures in home runs only once. In nine major-league seasons, interrupted by World War II, he compiled a .311 batting average without ever making an All-Star team. He continued hitting over .300 in the minors until he was nearly 45. But playing the outfield was an adventure — or misadventure.

Taft Shedron Wright was born in Tabor City, North Carolina, on August 10, 1911, to Rosa Jane (Williams) and Isaac Wright, a mill hand. They named him for the president of the United States. The family moved to Lumberton, North Carolina, where Isaac worked a tobacco farm. Sportswriters often called Taft a hillbilly because of his pronounced drawl, but few hills rise above the flatlands around Lumberton.

His older brother, Fred, a catcher for the town team, drafted his little brother to pitch to him. Taft joined the team as a teenager and had hopes for a pro career. He tried out for the Piedmont League team in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1931, but was cut during spring training. The next year he pitched for a semipro textile mill team in Lancaster, South Carolina, in an exhibition game against the Class-B Charlotte club. The right-hander’s fastball did not impress Charlotte manager Jimmy Dobbs, but Dobbs took notice of the line drives jumping off his bat.

“Son, a fellow who can hit like you doesn’t have any business pitching,” Dobbs told him. “You have a job with Charlotte next year if you want to play outfield.”3 The 21-year-old subtracted two years from his age when he signed with the Hornets, a Cardinals farm team, and stuck to that fiction throughout his career.4 In his first professional game, in 1933, he went 5-for-5, capped off with a ninth-inning grand slam. His father died that year, and he had to support his mother and sister.

When Wright advanced to the top level of the minors at Double-A Albany, New York, two years later, Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith scouted him and bought his contract. After two seasons at Chattanooga, Wright joined the Senators, also called the Nats, for spring training in 1938.

Manager Bucky Harris thought Wright might make a useful pinch-hitter if he could lose weight. Standing 5-foot-10, Wright preferred to play at 190 pounds, but the scales sometimes scrolled up to 220. Harris ordered him to run laps while outfitted in a rubber suit. After Wright sweated for several weeks, Washington Evening Star writer Francis Stan said he was still “built like a beer can.”5

Arriving in Greenville, South Carolina, for an exhibition game, the Nats found the field a muddy mess. Rather than risk injury to his regulars, Harris put in the B team with Wright in right field and had them wear high-top football shoes to protect their ankles. Wright hit a homer, double, and single, and homered again the next day. He made the team.

The presidential namesake opened the season in the nation’s capital in a platoon with fading star Al Simmons. Harris put him in right field, the easiest garden in Griffith Stadium. That lasted just eight games. After Wright let a fly ball drop in a critical spot, he was consigned to pinch-hitting.

On July 13 the Nats trailed the 19-year-old Cleveland phenom Bob Feller 3-1 with two out in the bottom of the ninth. Pinch-hitter Wright slashed an opposite-field double to bring home the two tying runs, then scored the winner on Buddy Lewis’s single. Feller became an easy mark for Wright. He hit .320 in 75 at-bats against the dominant pitcher of his time, who held American League batters to a .231 average during his career.

Wright delivered 13 pinch-hits in 39 at-bats (.333), almost exclusively against right-handed pitchers. In September Harris put him in the lineup full time as a tryout for next year. He stepped up to the challenge by hitting .381 in his last 24 games. When the final batting averages were posted, Wright led the league by a whisker at .34980 (rounded up to .350) to Jimmie Foxx’s .34867 (.349).

However, Wright had played in only 100 games, just 61 of them in the field, while Foxx appeared in 149. Many writers thought 100 games was the minimum qualification for the batting title, but if there was an official rule, nobody seemed to know about it. The Sporting News said Wright wasn’t eligible because he “was in not quite two-thirds of his team’s games and went to bat only 263 times.”6 (He had 263 at-bats, 282 plate appearances.)

While there was some discussion in the papers, most writers believed Foxx should be crowned champion as a matter of simple justice. Even Wright’s hometown Washington Star sports editor, Francis Stan, commented, “It isn’t unfair to recognize Foxx. In fact it would be unfair to give it to Wright.”7

During the winter, the official Reach Baseball Guide said an American League rule required 400 at-bats to qualify.8 That was news to almost everyone; no press report had mentioned such a rule, and there is no evidence that the league had ever announced one. Just six years earlier Foxx had been denied the 1932 crown when Boston’s Dale Alexander finished at .367 in 392 at-bats, edging out Foxx’s .364. That was the year Foxx challenged Babe Ruth’s home run record and finished with 58. Since he led the league in RBIs as well as homers, the batting title would have given him the Triple Crown — and, as it turned out, he would have been the only man to win two in a row because he led in all three categories the following year.

A batting championship was a coveted achievement in 1938 and for decades afterward; it meant money and fame. But there was no rational argument for awarding it to Wright, who had spent most of the season on the bench.

Now he had to prove that he could put up similar results playing regularly. During the offseason Griffith disposed of his two power hitters, Simmons and Zeke Bonura. He gave Wright a raise from $3,000 to $5,000 and was counting on him to pick up the slack in 1939.

Wright’s weight landed him in the owner’s doghouse during spring training, but he started the season hot. “Taft Wright will plaster major league pitching as long as he can waddle up to the plate,” Evening Star reporter Burton Hawkins wrote.9 During a nine-game splurge in July, Wright hit .500 with a pinch-hit game-winning homer and a 5-for-5 day. Batting cleanup, he finished with 93 RBIs and a .309 average. But the American League was a hitter’s league that year, so his 109 OPS+ was not impressive.

Griffith wasn’t satisfied, complaining that “he isn’t much of a baserunner and fielder” and adding a backhanded endorsement: “Taft is set until somebody comes along that is better.”10 Manager Harris thought he knew somebody better: Gee Walker, whom he had managed with the Tigers. The Nats traded Wright and pitcher Pete Appleton to the White Sox for Walker.

With Wright installed in right field, Chicago also acquired Moose Solters, whose glove was equally suspect, to stand in left. A writer suggested that center fielder Mike Kreevich had better prepare himself to cover all three positions.

The Indians’ Bob Feller welcomed the White Sox to Cleveland to begin the 1940 season by spinning the first Opening Day no-hitter in history. Wright bid to break it up in the fourth with a long drive to right, but Ben Chapman hauled it in on the run. With two away in the bottom of the ninth, Wright smashed a hard liner that second baseman Ray Mack lunged to his left to knock down, then recovered to throw to first for the final out. “That was the hardest ball hit at me all day,” a relieved Feller said.11

In Wright’s next game he took off on an 18-game hitting streak that raised his average above .400. For most of the year he and teammate Luke Appling vied for the lead in the race for the batting title. Playing every day, he had a chance to win it for real this time, but he cooled to finish at .337, in seventh place.

Before spring training in 1941, the Sox sent Wright, Solters, and pitcher Eddie Smith — dubbed the Fat Man Club — to the resort in Hot Springs, Arkansas, to boil off some flab. Coach Mule Haas went along as chaperone to protect them from the mashed potatoes. Three weeks of soaking and hiking may have shrunk Wright’s waistline, but he caught the flu, spent time in a hospital, and missed the first two weeks of the season. Still weak when he went into the lineup, he didn’t get his batting average up to .300 until July. He wound up at .322 with10 home runs and 97 RBIs, both career-highs.

After Pearl Harbor, Wright’s draft board in Lumberton classified him 3-A, deferred from service because he was supporting his mother and sister, although he was unmarried. He thought he was safe, but found out otherwise when the board summoned him for a physical exam in July. Expecting to be called up at any time, he brought his hometown girlfriend to Chicago. He had known Marie Grooms Prevatt since they were children; she was divorced with a young son. On July 25, 1942, Wright went 1-for-3 and married Marie after the game. He was back in the lineup for a doubleheader the next afternoon.

He was hitting .333 with an OPS+ of 140 in 85 games when he played for the last time on August 26. He was sworn into the Army Air Forces a few days later, assigned to Fort Bragg, North Carolina. His wartime duty was playing ball, eventually in Hawaii on an all-star team of major leaguers that toured island bases in the Pacific. Sergeant Wright was discharged on November 15, 1945, and sent a postcard to White Sox vice president Harry Grabiner announcing his return.

With the war veterans back in baseball flannels in 1946, the game entered a period of unparalleled popularity. Crowds were bigger and louder; they cheered louder and booed louder. To begin the season, Feller faced the White Sox again and bid for another Opening Day no-hitter. It lasted only until the fourth, when Wright broke it up with a single.

Now 34 years old, Wright never got untracked. He came down with a sore throat and had his tonsils removed in June. His final batting average slipped below .300 for the first time, to .275. Although he had played service ball, he complained that his baseball muscles weren’t ready for everyday work. He wasn’t the only returning veteran who floundered; Joe DiMaggio, for one, also dropped below .300 for the first time.

Wright claimed to hate pitchers, but he was harder on himself than the men on the mound. When he failed to get a hit, he would yell at himself, giving himself pep talks. He declined to name the toughest pitchers he faced. “When I really am strokin’ that apple, I torture them all,” he said. “When I’m not getting hold of the ball right any humpty dumpty can get me out.”12

Taft and Marie had a daughter, Sherry, born shortly after he went into the service, and their son Taft Jr. came along in 1947. The baby became ill and needed surgery during the season. Perhaps distracted, Wright struggled on the field; his average fell to .224 in June. Then he picked up and began hitting like his young self. In the second half he challenged Ted Williams for the batting title, although he said, “Never in my braggiest moments did I claim to be the kind of hitter Ted Williams is.”13 He finished fourth in the league at .324. With just 17 extra-base hits, he had turned into strictly a slap hitter. His .320 lifetime average trailed only Williams, DiMaggio, and Boston’s Johnny Pesky among active American Leaguers.

During a postseason barnstorming tour organized by his Washington teammate Buddy Lewis, Wright was hit by a pitch that broke a bone in his left wrist. It was his last time barnstorming. He sold his Lumberton farm and moved his family to Orlando, Florida, where he coached at former major leaguer Joe Stripp’s winter baseball school in future offseasons.

The White Sox raised his salary to $17,000, the highest of his career, but 1948 turned into a nightmare year. Wright’s wrist was still bothering him, and he hit only .279 with no power. The club sank to the bottom of the standings, losing 101 games. After the season the Sox hired a new general manager, Frank Lane, to clean house. On his first day he sold Wright to the Philadelphia Athletics.

Manager Connie Mack wanted Wright as a pinch-hitter. He started only 31 games in the outfield in 1949. In one of them, he leaped for a line drive and it hit him squarely in the forehead. Wright batted just .235 and was released in September.

Several major-league teams expressed interest, but they offered only spring tryouts with no guarantee. Wright signed with the Triple-A Louisville Colonels, who trained near his Orlando home. He played for Louisville for three years, and his batting average stayed above .300 until he turned 40. After the Colonels released him, he joined Triple-A Ottawa in 1953 and hit .353 in part-time play.

While he was back in Ottawa the next year, his third child was born in Orlando. The boy was named James Lyons Wright after his father’s White Sox managers, Jimmy Dykes and Ted Lyons.

Ottawa manager Les Bell got into an argument with veteran slugger Luke Easter in July, and the two had to be restrained in the dugout. Wright replaced Bell as manager the next day. The Senators were in last place, but rallied to win more than they lost in the first few weeks under the new boss. Wright said he followed Connie Mack’s advice and tried to keep the players happy.14 They may have been happy, but they fell back to the cellar by the end of the season.

He managed the Class-B Amarillo Gold Sox for part of 1955, then returned home to manage the Orlando Sertomans in ’56. Gee Walker, who had been traded for him, was the GM. The 44-year-old Wright never lost his batting stroke; he was hitting .353 on July 15 when he was ejected from a game. Walker fired him the next day and took over as manager, possibly to save a salary, because the club was playing to empty seats.

Finally done with baseball, Wright ran a bar in Orlando for many years, catering to ballplayers who hung out there during spring training. When poor health forced him to sell his business, he tended bar at the local VFW hall until he died of a heart attack at 70 on October 22, 1981.

Wright lived long enough to see the first million-dollar players, Nolan Ryan and Dave Parker, but he expressed no resentment of their big paychecks. “There are a lot of us old ballplayers in the same pay boat,” he said. “No need to cry about it. You just try to live long enough to collect your pension.”15

Acknowledgments

Photo credit: Bowman Gum Co. This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jan Finkel, and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Ed Burns, “Taffy’s Toughest Tirades to Himself Helped Him Soften Up Pitchers,” The Sporting News, October 22, 1947: 17.

2 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, October 3, 1938: X15; Francis E. Stan, “Wright, Batting at .560 Clip, to Play Right for Nats at Home,” Washington Evening Star, April 14, 1938: D-1. Although Wright answered to the nickname “Taffy,” he was usually called Taft.

3 David Condon, “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, October 28, 1981: D3

4 Wright gave his birth year as 1913 on a player questionnaire he filled out for the National Baseball Hall of Fame around 1946.

5 F.E.S. (Francis E. Stan), “Meet the Nationals,” Washington Evening Star, March 23, 1938: 33

6 “Foxx Seventh Infielder in Row to Lead American League Batters,” The Sporting News, December 29, 1938: 6.

7 Stan, “Win, Lose or Draw,” Washington Evening Star, December 27, 1938: A-10.

8 Quoted in Pete Palmer et. al., eds, Total Baseball 8th ed. (Toronto: Sport Classic, 2004), 956. The 400 at-bat rule was adopted by both leagues for the 1950 season, and changed to 3.1 plate appearances per team game five years later.

9 Burton Hawkins, “Masterson Makes Strong Bid for Nats’ Prize Rook Title in Scoring Over Tigers,” Washington Evening Star, May 18, 1939: C-1

10 “Griff Seeks Permission for Ortiz and Pitko to Prime in Winter Loop,” Washington Evening Star, July 31, 1939: A-15

11 “Feller Says He Wasn’t Sure of No-Hitter until Last Out,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 17, 1940: 20.

12 Burns, “Taffy’s Toughest Tirades.”

13 Burns, “Taffy’s Toughest Tirades.”

14 Cy Kritzer, “International League,” The Sporting News, August 25, 1954: 25.

15 Charlie Wadsworth, “A farewell to baseball hero Taft Wright,” Orlando Sentinel, October 26, 1981: 4-B.

Full Name

Taft Shedron Wright

Born

August 10, 1911 at Tabor City, NC (USA)

Died

October 22, 1981 at Orlando, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.