Theodore Breitenstein

Like Steve Carlton, who won 27 of his team’s 59 victories in 1972, Theodore Breitenstein was a left-handed ace on a weak team. Breitenstein was credited with 43 percent of the St. Louis Browns’ victories from 1893 to 1896. In 21 seasons of professional baseball from 1891 to 1911, the durable southpaw won more than 325 games.1

Like Steve Carlton, who won 27 of his team’s 59 victories in 1972, Theodore Breitenstein was a left-handed ace on a weak team. Breitenstein was credited with 43 percent of the St. Louis Browns’ victories from 1893 to 1896. In 21 seasons of professional baseball from 1891 to 1911, the durable southpaw won more than 325 games.1

“Theodore Breitenstein was at one time the greatest left-handed pitcher in America.” — Alfred H. Spink, founder of The Sporting News 2

“Breitenstein is one of the few left-handers who can locate the plate when he wants to, and in addition to this he has terrific speed, sharp curves, and there is not a pitcher in the league that fields his position better.” — Wee Willie Keeler, 18973

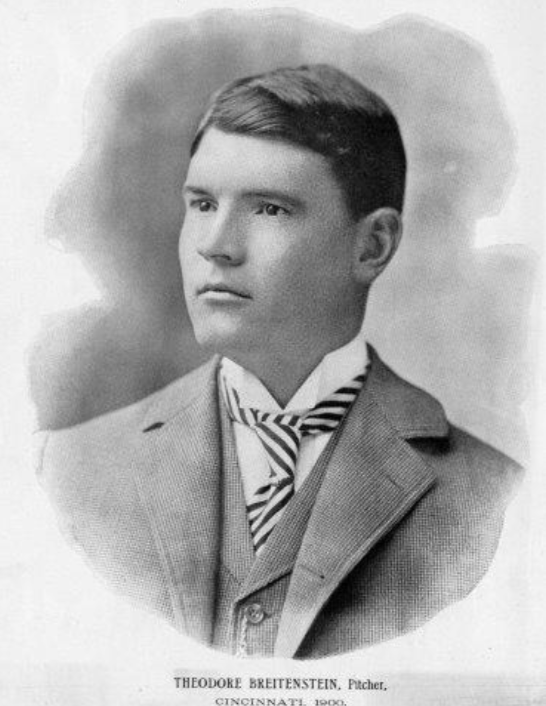

Breitenstein was a freckled-faced redhead. His nickname was “Breit” (rhymes with write). He was also called Red, Theo, and “The,” the first syllable of Theo.4 Unlike Carlton, Breitenstein was small, 5-feet-9, and weighed between 137 and 150 pounds early in his career, increasing to 167 pounds later on.5

Born on June 1, 1869, in St. Louis, Theodore J. Breitenstein was the youngest of the three children of German immigrants Louis Breitenstein (1822-1888, a cabinet maker) and Elizabeth (Moore) Breitenstein (1825-1883).6 Louis and Elizabeth died when Theodore was a teenager. Theodore went to work making cookstoves for the Wrought Iron Range Company of St. Louis and played on the Home Comforts, a baseball team named for the company’s brand of ranges and furnaces. With Theodore pitching, the team won the 1889 St. Louis Baseball League championship game.7

In 1890 Breitenstein was one of the Brown Reserves, a group of promising amateurs permitted by St. Louis Browns owner Chris Von der Ahe to practice at the Browns’ ballpark.8 This led to Breitenstein joining the Browns in 1891. He made his major-league debut on April 28, pitching two scoreless innings in relief against the Louisville Colonels.9 He went to the Grand Rapids (Michigan) Shamrocks in May and returned to the Browns in August.10 On October 4, the last day of the season, Breitenstein made his first major-league start and threw a no-hitter against the Colonels. Except for one base on balls, it was a perfect game. The 22-year-old hurler did not realize he had a no-hitter going until the game was over; his teammates had kept mum so that he would not get rattled.11

After hearing “tales of pitcher Breitenstein’s drinking,” Von der Ahe had doubts about his future.12 Breitenstein pitched erratically for the Browns in 1892. On April 15 he hurled a three-hitter against the Pittsburgh Pirates, but a week later the Pirates hammered him for 12 runs in the first inning.13 On April 24 Breitenstein allowed 12 hits and nine walks in a 10-2 loss to the Cincinnati Reds, yet on May 6, he had a no-hitter through eight innings against the Brooklyn Grooms en route to a two-hitter, albeit with seven walks.14 On May 14 he walked 10 batters in a 5-3 loss to the Chicago Colts, but a week later he outpitched Cy Young in a 4-1 victory over the Cleveland Spiders.15

The roller-coaster continued throughout the season. In early June Breitenstein was knocked out in blowout losses to the Philadelphia Phillies and Baltimore Orioles.16 Then he tossed a two-hitter against Louisville on June 20, and four days later went the distance against Cy Young in a 16-inning, 3-3 tie.17 Sporting Life cautioned Breitenstein in July:

“Breitenstein and jag juice [hard liquor] have been trotting a rapid heat lately. … He is the only player on the team who has been fined this season, and if he insists on dallying with the stuff that purloins the brain an indefinite suspension will be the result. But he is a good-natured, hard-working lad, and he ought to think it over a couple of times before following … the ruddy road to ruin.”18

Von der Ahe suspended Breitenstein for part of August and September.19 The Browns finished in 11th place in the 12-team National League. Breitenstein compiled an unimpressive 9-19 record and 4.69 ERA in 282⅓ innings, yet his nine wins were second most on the Browns’ pitching staff.

In 1893 the pitching distance was increased from 50 feet to 60 feet 6 inches. This sparked a 29 percent increase from 1892 in National League scoring per game. The new distance suited Breitenstein. He pitched 382⅔ innings in 1893, led the league with a 3.18 ERA, and posted a 19-24 record for the 10th-place Browns. Highlights included a two-hit shutout of Cap Anson’s Chicago Colts on May 7, and a two-hitter against John Ward’s New York Giants on the Fourth of July.20 Breitenstein’s favorite catchers were Dick Buckley and Heinie Peitz; he credited Buckley for his success as a pitcher.21 The German duo of Breitenstein and Peitz became known as the Pretzel Battery.22

After a doubleheader in St. Louis on August 1, 1893, the Browns traveled to Louisville for a three-game series. Along the way, they stopped to play an exhibition game at Vincennes, Indiana. Breitenstein “filled up on Indiana whisky” and refused to board the train to Louisville; three teammates “attempted by main force to put Breitenstein on the train, but failed.”23 After sobering up, he returned to the team and apologized to Von der Ahe.24

In 1894 Breitenstein was overworked, underpaid, and bullied by Von der Ahe. He pitched 447⅓ innings, the most innings in one season by a National League pitcher from 1894 to 2014. His 27-23 record was remarkable on a team with a 56-76 record. His ERA jumped to 4.79 but was better than the league average of 5.33. Sporting Life said, “Breitenstein is one of the lowest-salaried and most effective pitchers in the League.”25 Breitenstein’s contract paid him a meager $1,350 for the season and included a “temperance” clause that permitted Von der Ahe to fine him $100 for each time he was caught drinking; this fine was levied once during the season.26 According to reporter O.P. Caylor, Von der Ahe liked to swear at Breitenstein in German and “know that he is understood.”27

Breitenstein’s relentless workload and rocky relationship with Von der Ahe were demonstrated during a doubleheader against Brooklyn on September 9, 1894. He pitched a complete game in the first game, and the Browns won, 7-5. He had thrown complete games on September 1, 3, 6, and 9, and pitched in relief on September 4 and 8.28 Nonetheless, after two St. Louis hurlers were battered in the second game of the doubleheader, Von der Ahe wanted to put Breitenstein into that game, too, and was angered that he had changed out of his uniform. Von der Ahe ordered him to put his uniform on and go in to pitch. Breitenstein refused, so Von der Ahe fined him $100 and suspended him.29 Breitenstein explained:

“The cranks [baseball fans] have but a slight appreciation of the fearful strain a pitcher’s arm is subjected to. A man who takes his regular turn in the box ought to be asked to do extra work only in case of an emergency. I have had but little trouble with my arm and seldom complain when called on to go into the points. I make it a rule to trust the straight ball and change of pace until a man gets on base, when I resort to the [more strenuous] drop and curved ball to outwit an opponent. … I don’t loaf in the box, but I adopt this system of saving my arm.”30

Breitenstein returned to action on September 15 in St. Louis and was defeated 7-2 by the Giants.31 That evening the 25-year-old pitcher married 18-year-old Ida L. Uhlmansick. Like Breitenstein, Ida was a native of St. Louis and a child of German immigrants.32 She was “a pretty German girl, with eyes that are blue and hair that is blond.”33 Breitenstein promised to be a model husband, and Ida said she would lock him in at night if necessary.34 The couple resided in St. Louis. In the offseason Breitenstein worked at a stove foundry as a machinist.35 He was said to be “a first-class workman” with “not a lazy bone in his body.”36

Breitenstein rejected Von der Ahe’s initial offer of $1,800 and signed for $2,000 for the 1895 season.37 The Browns were even weaker in 1895 than in 1894. Statistics published by the Pittsburgh Daily Post on August 5, 1895, indicate that Breitenstein’s won-lost record was 16-18 when the rest of the St. Louis pitching staff had a combined record of 12-41.38 Von der Ahe turned down offers of $10,000 for Breitenstein from both the Phillies and Pirates, an enormous sum for that era.39 Breitenstein was the most popular player in St. Louis, and “St. Louis patrons were up in arms against” any sale of the hometown favorite.40 Sporting Life said, “The League should insist on making Von der Ahe keep his great pitcher, Breitenstein, as the sale of this young man will be the deathblow to base ball in St. Louis.”41

Breitenstein finished the 1895 season with a 19-30 record in 438⅔ innings, and the Browns landed in 11th place with a 39-92 record. He was credited with 49 percent of the team’s wins (19 of 39); no pitcher won a greater percentage of his team’s victories from 1893 to 2014.42 Reportedly, Breitenstein “dissipated” (abused alcohol) on one road trip.43 Despite losing 30 games, he was wanted by every team in the league. Sporting Life said: “What a good-natured, hard-working little wonder he is. The balls come in over the plate like a zig-zag streak of lightning, and there is not a moment’s rest for him in the whole nine innings. … He has the nerve and the heart and the equilibrium of temper and the modesty, and yet with it all the confidence, too.”44

In 1896 St. Louis again finished in 11th place, with Breitenstein earning 18 of the team’s 40 victories. The Cincinnati Reds acquired him after the season for a reported $10,000. Thrilled to leave Von der Ahe, Breitenstein demonstrated what he could do on a good team. In 1897 he compiled a 23-12 record for the fourth-place Reds, including 10 consecutive victories from June 11 to July 18. The Cincinnati Enquirer said, “Some of those who in the early spring used to refer to Breit as a ten-cent counterfeit, are now quite ready to take off their hats to him as the only genuine, blown-in-the-glass, Ten-Thousand-Dollar-Beauty in the business.”45 Breitenstein enjoyed his three-hit shutout of St. Louis on June 30, with Von der Ahe looking on.46 Without Breitenstein, St. Louis won only 29 games; the 1897 Browns, with a .221 winning percentage, rank as the second worst major-league team between 1891 and 2014.

The Pretzel Battery was reunited when Breitenstein joined the Reds. He and Peitz were a clever pair. They would “argue” with each other during pivotal moments of a game. Breitenstein described the ploy:

“The batter, of course, is interested in the supposed quarrel, and when he sees that Peitz apparently is not ready to catch, he takes his eye off the ball. Then Heinie gives me the sign, and I shoot it over. The batter either hits late at the ball and pops it up, or misses it entirely. I tell you, we have pulled out of many a tight hole with that trick.”47

With Peitz behind the plate, Breitenstein outdueled Cy Young on Opening Day in 1898.48 A week later, against Pittsburgh, Breitenstein hurled his second career no-hitter.49 After shutting out Cleveland on September 4, he had an 18-8 record and the Reds were in first place with a 1½-game lead over the Boston Beaneaters. The Beaneaters won 30 of their remaining 35 games to capture the pennant, while the Reds fell to third place, 11½ games back. Breitenstein finished the season with a 20-14 record. He was bothered by a sore arm late in the season, and an X-ray revealed a bone spur near his left elbow.50

Breitenstein’s arm troubled him in the spring of 1899,51 but he pitched well for the Reds in 1899 and 1900. In February 1901, the St. Louis Republic lobbied for his return to St. Louis.52 The Reds complied by releasing Breitenstein, and he signed with the St. Louis Cardinals. After he pitched poorly in three starts, though, the Cardinals released him. Breitenstein “gave no indication of any of his former prowess, and the necessity of reducing [the Cardinals] to the League limit of 16 men by May 15 forced his release.”53 This ended his major-league career, a few weeks before his 32nd birthday. Breitenstein had thrown 301 complete games in the major leagues, establishing a record for southpaws that has been exceeded by only Eddie Plank and Warren Spahn in major-league history through 2015.

Beginning in June 1901, Breitenstein pitched for the St. Paul (Minnesota) Saints of the Western League, but the team released him in August “in the interests of good discipline.”54 He finished the season with the semipro Alton (Illinois) Blues.55 In December Breitenstein was thrown from a horse-drawn carriage and broke his right (nonpitching) arm.56 That winter was a low point in his life, both physically and mentally, and he said he would never again play baseball.57

Breitenstein’s friend and former teammate Charlie Frank, who managed the Memphis Egyptians of the Southern Association, persuaded him to return to baseball as a member of the Egyptians.58 Breitenstein posted a 21-11 record for Memphis in 1902. One of his six shutouts was a three-hitter against the New Orleans Pelicans on June 24; the “New Orleans left-handed batters found Breitenstein an unsolvable proposition” and opted to bat right-handed against him.59

Breitenstein still had the stuff to pitch in the major leagues, but he turned down a chance to join Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics in the spring of 1903.60 With six shutouts and a 17-11 record, Breitenstein helped the Egyptians win the 1903 Southern Association pennant. On September 19 his triple knocked in two runs in his 3-0 shutout of the Atlanta Crackers; the Memphis “crowd went frantic and a subscription of $75 was taken up for the pitcher.”61 Despite the appreciation shown in Memphis, Breitenstein was loyal to manager Frank and followed him the next season to New Orleans.

Breitenstein pitched spectacularly for the New Orleans Pelicans from 1904 to 1906, with a 57-20 record and a 1.50 ERA. The Pelicans won the 1905 Southern Association pennant. The Philadelphia Athletics and St. Louis Browns tried to lure Breitenstein back to the major leagues, but he declined.62 Earning a $2,700 salary in New Orleans, he was better paid than many major-league hurlers.63

Following an offyear in 1907, Breitenstein was exceptional in 1908, with a 17-6 record and a minuscule 1.05 ERA. Over the final two months of the season, he threw seven shutouts. A dramatic showdown occurred on September 19, the last day of the season. The Pelicans needed to defeat the Nashville Volunteers to win the pennant; otherwise, Nashville would take the flag. Nashville won the game, 1-0, in “a brilliantly contested pitchers’ battle between Carl Vedder] Sitton and Breitenstein.”64 Sportswriter Grantland Rice called it “the greatest game ever played in Dixie.”65

Breitenstein was known as “The Grand Old Man” of the Southern Association. The Cleveland Plain Dealer said: “He is a little, weazened up old man with furrows on his face. … His looks are typical of a player who has baked beneath the boiling suns on a ball field season after season.”66 At age 40, “the wise old owl” pitched a no-hitter against the Montgomery (Alabama) Senators on August 15, 1909; the Senators “were utterly unable to connect” with his offerings.67 It was the third no-hitter of his professional career, and it came 18 years after his first. On August 27 Breitenstein threw an 11-inning, two-hit shutout against the Birmingham Barons.68 He followed that with a 12-inning, three-hit shutout of Montgomery on September 5.69

New Orleans won the 1910 Southern Association pennant by a comfortable eight-game margin over second-place Birmingham. Breitenstein compiled a 19-9 record and a 1.53 ERA, with eight shutouts; however, the brightest star on the Pelicans was Shoeless Joe Jackson, a sensational 22-year-old center fielder who led the league with a .354 batting average. The next season was Breitenstein’s last as a player, and at age 42, he helped the Pelicans win another pennant. He stayed in the Southern Association as an umpire from 1912 to 1918.

After leaving baseball, Breitenstein was employed at a Ford assembly plant, and later at Forest Park, in St. Louis. He enjoyed watching major-league games at Sportsman’s Park,70 but felt the pitchers were pampered. “Now, if a boy is hit in the first couple of innings, they put the blankets on him and he’s through for four days,” he said in 1929. “We worked three or four times a week, and lots of times played the outfield when we weren’t pitching.”71

Breitenstein offered advice to young pitchers:

- “More batsmen are fooled by change of pace than by all the speed, curves or shoots in the world. A good change of pace is the most valuable faculty a pitcher can possess.”72

- “Study your batters. If you know he likes a high ball give him a low one and vice versa. Not all the time, of course, for if they know what is coming they are liable to lay for it. Mix them up at unexpected moments.”73

- “Never pitch for strike-outs. Their day is over. Always remember that you have eight men to help you.”74

Ida Breitenstein died on April 25, 1935. Heartbroken over the loss of his wife, Theodore died eight days later of heart failure, at the age of 65.75 They are buried at St. Peter’s Cemetery in St. Louis.76

“Over the hills to the Old Men’s Home

Rattles the dismal car.

Famous fielders and willow wielders

Have made the journey far.

Countless the inmates all down and out,

Never again to star.

But silky fine is T. Breitenstein,

The Grand Old Man ain’t that!”77

— Pointers from Pelicanville, 1910

This biography appears in SABR’s “No-Hitters” (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 In 2015 Baseball-reference.com indicated that Breitenstein had earned 160 major-league wins and 165 minor-league wins, for a total of 325 wins in professional baseball; however, his 1891 minor-league record is not included in this tally.

2 Alfred H. Spink, The National Game, 2nd Edition (St. Louis: National Game Pub. Co., 1911), 124.

3 Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Daily Independent, July 9, 1897.

4 Although record books give his name as Ted Breitenstein, the research for this biography found no evidence that he was called Ted by his contemporaries.

5 The Sporting News, April 5, 1934.

6 Ancestry.com. Theodore’s middle initial is given as “J” in the 1910 US Census and in 1895 and 1917 St. Louis city directories.

7 Spink, The National Game, 53.

8 The Sporting News, April 5, 1934; St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 16, 1890.

9 Chicago Tribune, April 29, 1891.

10 Fort Wayne (Indiana) Sentinel, August 6, 1891.

11 The Sporting News, February 21, 1929. Breitenstein (1891), Bumpus Jones (1892), and Bobo Holloman (1953) were the only pitchers to throw a no-hitter in their first major-league start, through 2014.

12 Sporting Life, March 12, 1892.

13 Pittsburgh Dispatch, April 16 and 23, 1892.

14 Sporting Life, April 30, 1892; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 7, 1892.

15 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 15, 1892; Los Angeles Herald, May 22, 1892.

16 Chicago Inter Ocean, June 7, 1892; Pittsburgh Daily Post, June 11, 1892.

17 St. Paul Globe, June 21, 1892; San Francisco Call, June 25, 1892.

18 Sporting Life, July 2, 1892.

19 St. Paul Globe, September 19, 1892.

20 Chicago Tribune, May 8, 1893; Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 5, 1893.

21 Sporting Life, January 25, 1896.

22 New York World, July 12, 1893.

23 Sporting Life, August 12, 1893.

24 Chicago Tribune, August 5, 1893.

25 Sporting Life, May 12, 1894.

26 Sporting Life, March 17, 1894; Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 17, 1894.

27 Kansas City (Kansas) Gazette, May 13, 1894.

28 Washington Times, September 2 and 5, 1894; Philadelphia Times, September 4, 1894; Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 7, 1894; Chicago Inter Ocean, September 9, 1894.

29 Sporting Life, September 13, 1894; Scranton (Pennsylvania) Tribune, September 14, 1894.

30 Springfield (Missouri) Leader, September 17, 1894.

31 Richmond (Virginia) Dispatch, September 16, 1894.

32 Ancestry.com.

33 Sporting Life, September 22, 1894.

34 Ibid.

35 Sporting Life, December 9, 1893, and November 24, 1894.

36 Sporting Life, October 31, 1896.

37 Philadelphia Times, January 26, 1895; Sporting Life, March 9, 1895.

38 Pittsburgh Daily Post, August 5, 1895.

39 New York Tribune, June 9, 1895; Pittsburgh Daily Post, July 9, 1895.

40 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 25, 1895; Sporting Life, August 3, 1895.

41 Sporting Life, July 20, 1895.

42 SABR, The SABR Baseball List & Record Book: Baseball’s Most Fascinating Records and Unusual Statistics (New York: Scribner, 2007), 266.

43 Sporting Life, July 13, 1895.

44 Sporting Life, June 22, 1895.

45 Cincinnati Enquirer, July 19, 1897.

46 The Sporting News, July 3, 1897.

47 Sporting Life, August 13, 1898.

48 Cincinnati Enquirer, April 16, 1898.

49 Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1898.

50 Sporting Life, August 27 and September 10, 1898; Kansas City Journal, December 18, 1898. X-rays were discovered in 1895 by Wilhelm Roentgen. The X-ray of Breitenstein’s arm in 1898 is an early example of the use of X-rays in sports medicine.

51 Louisville Courier-Journal, May 8, 1899.

52 St. Louis Republic, February 3, 1901.

53 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 12, 1901.

54 Minneapolis Journal, June 3 and August 16, 1901.

55 St. Louis Republic, August 31, 1901.

56 Sedalia (Missouri) Democrat, December 9, 1901.

57 Sporting Life, January 25, 1902.

58 Atlanta Constitution, March 31, 1902.

59 New Orleans Times-Picayune, June 25, 1902.

60 Mansfield (Ohio) News, May 16, 1903.

61 Atlanta Constitution, September 20, 1903.

62 Washington Times, September 2, 1905; Atlanta Constitution, September 9, 1905.

63 Washington Post, December 12, 1905.

64 Sporting Life, October 3, 1908.

65 John A. Simpson, The Greatest Game Ever Played in Dixie: The Nashville Vols, Their 1908 Season, and the Championship Game (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007), 25.

66 Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 28, 1909.

67 New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 16, 1909.

68 Sporting Life, September 4, 1909.

69 Sporting Life, September 18, 1909.

70 The Sporting News, April 5, 1934.

71 The Sporting News, February 21, 1929.

72 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 10, 1896.

73 Ibid.

74 Ibid.

75 Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 4, 1935.

76 http://stpeterschurch.org/cemetery/cemetery_SearchResults.php?S=2&L=124.00&LO=1.

77 New Orleans Times-Picayune, July 30, 1910.

Full Name

Theodore J. Breitenstein

Born

June 1, 1869 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

May 3, 1935 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.