Tom Bradley

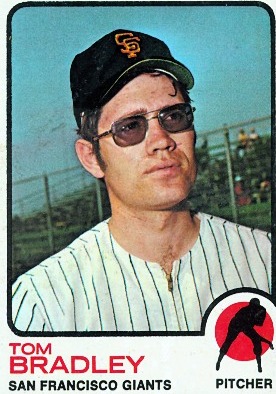

Tom Bradley was a Latin scholar, a coach and teacher, and for three seasons in the early 1970s, a workhorse pitcher for would-be contending teams desperate for quality innings. Bradley pitched in seven major-league seasons, most notably for the Chicago White Sox in 1971-72 and for the San Francisco Giants in 1973. Over that span, the right hander’s won-lost record was 43-41. None of his teams won pennants, but Bradley pitched 769 innings, helping his teams improve their records and play meaningful games. When arm trouble ended his pitching career at the age of 29, Bradley spent 33 seasons coaching in college, then the minor leagues.

Tom Bradley was a Latin scholar, a coach and teacher, and for three seasons in the early 1970s, a workhorse pitcher for would-be contending teams desperate for quality innings. Bradley pitched in seven major-league seasons, most notably for the Chicago White Sox in 1971-72 and for the San Francisco Giants in 1973. Over that span, the right hander’s won-lost record was 43-41. None of his teams won pennants, but Bradley pitched 769 innings, helping his teams improve their records and play meaningful games. When arm trouble ended his pitching career at the age of 29, Bradley spent 33 seasons coaching in college, then the minor leagues.

Thomas William Bradley was born on March 16, 1947, in Asheville, North Carolina, the only child of Claude and Dorothy Bradley. When Tom was an infant, the family relocated to Falls Church, Virginia, where both parents worked for the federal government. Claude was an accomplished amateur pitcher, and as Tom began playing baseball, his father became his primary instructor. An excellent student-athlete, Tom played both basketball and baseball, was named an all-area pitcher, and won a scholarship to the University of Maryland.

Bradley pitched at Maryland for coach Elton Jackson in 1967 and 1968. He was a combined 10-4, made the all-ACC team both years, and was an honorable mention Sporting News All-American. Enrolled in classics as a Latin major with a minor in Greek, Tom excelled academically and was a Maryland Scholar-Athlete of the Year. He graduated cum laude in 1972, returning to school after he had started his professional baseball career.

In June 1968, the six-foot-two, 180-pound Bradley was chosen in the seventh round of the amateur draft by the California Angels despite poor (20/450) vision that required him to pitch wearing glasses but was never a detriment to his control. Signed by Gil English and Al Monchak, Tom played for five teams in the Angels’ organization in his first season, 1969, rising from Class A all the way to the majors. He started with the Quad City Angels of the Midwest League where he compiled a 6-1 record. Tom then pitched well at El Paso and San Jose before reaching Hawaii of the AAA Pacific Coast League. There, despite an 0-2 record, he impressed manager Chuck Tanner and general manager Roland Hemond, leading to a year-end call-up.

Bradley made his major-league debut on September 9 for the parent Angels. He entered the game in the sixth inning against the Minnesota Twins with the Angels leading 7-3. In two-thirds of an inning, Tom gave up four hits, including a home run by Leo Cardenas. Five runs scored in the inning and Bradley took the loss.

The 1970 season opened with Bradley back at Class AA El Paso, acquiring more professional experience. The stay there was short as Tom went 3-0 in four appearances with a 2.03 ERA; he was promoted back to Hawaii and Chuck Tanner. Tanner and the Islanders were on their way to the South Division pennant in the Pacific Coast League, and Tom Bradley was a major part of this success. Over 16 starts at Hawaii, he had an 11-1 record with a 2.53 ERA and earned another call-up to the Angels, this time at midseason.

Bradley made his first major-league start on July 8, 1970, against the Kansas City Royals. He pitched into the ninth with a 2-1 lead before being replaced by Ken Tatum, who picked up a tainted win, giving up the tying run on a bases-loaded walk before the Angels rallied. On August 2, Bradley earned his first win, taking an 8-0 lead into the ninth against Boston before Tony Conigliaro touched him up for a three-run homer.

The Angels stood three games behind the first-place Oakland A’s on September 3 when Bradley pitched his first major-league shutout, a seven-hitter against Kansas City. He fanned eight Royals and walked only one as the Angels won, 1-0. He finished the season at 2-5, 4.13. The Angels faded in September, finishing third with an 86-76 record.

Looking to 1971, California sought players that might bring a division championship. One position under scrutiny was center field where Jay Johnstone was the regular. Johnstone, 24, had not hit well in his five years in the majors. He was adequate defensively, but the Angels’ best hitter was Alex Johnson, statuesque in left field, where he needed help from a wider-ranging center fielder. In Chicago, Ken Berry, at age 30, appeared to be emerging as complete player. Berry had been a fixture in center field for Chicago since 1965, making a habit of catching would-be home runs over the top of the canvas center-field barrier. In 1970 he had hit a career-high .276. A Johnstone-for-Berry swap would have multiple advantages–maturity, better hitting, and a center fielder better able to cover part of left for Alex Johnson–but the Angels would have to sweeten the pot. Although a definite prospect, Bradley appeared to be expendable.

The Chicago White Sox of 1968-70 were a franchise in turmoil. After 17 consecutive winning seasons, the 1968 White Sox had finished tied with the California, 36 games out, at 67-95. Despite this downturn, the team’s fans had continued to support the Sox with attendance just under a million. But in both 1969 and 1970, the team’s performance had continued to slide. In 1970, the White Sox sagged to their worst-ever season record, 56-106, and drew less than half a million fans. Toward the end of that season, the White Sox fired manager Don Gutteridge and general manager Ed Short and looked to the Angels’ organization; Chuck Tanner took over as manager and Roland Hemond came in as an assistant to titular general manager Stuart Holcomb. Hemond got busy, making a number of multiple-player trades, looking for promising youth in exchange for established but aging players. On November 30, 1970, he acquired Johnstone, Bradley, and catcher Tom Egan from the Angels for Berry, pitcher Billy Wynne, and utility man Syd O’Brien. Continuing the theme, Hemond shipped 36-year-old Luis Aparicio to Boston the next day for two younger players.

And so, on April 7, 1971, Chicago opened the season in Oakland with a team of mostly unproven players and no place to go but up. Charley Finley, Oakland A’s owner-showman, saw the Opening Day doubleheader as a way to kick-start the season with two quick wins. Finley’s plans flopped as the Sox swept both games, 6-5 and 12-4, before returning to Chicago and their home debut.

On April 10, Tom Bradley (nicknamed “Omar” by his teammates, recalling the decorated World War II Army commander and later head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) made his first start in the White Sox rotation, a spot he would retain for two seasons. Facing the Minnesota Twins, Bradley pitched seven shutout innings before weakening in the eighth, allowing Minnesota two runs to tie the score. Vicente Romo pitched the top of the ninth and got the win when the Sox eked out a run in the bottom. The supposed-to-be-woeful White Sox were suddenly 3-0 and newcomer Bradley’s contribution showed definite promise.

The White Sox returned to 1970 form over the remainder of the season’s first 30 days with a 10-16 record. Tommy John and Bart Johnson were at the front of the rotation, Bradley third, with Wilbur Wood gradually working his way in. Bradley’s first six starts had resulted in a 3-1 record over 44 innings pitched. One of the three victories was a 4-0 shutout of the A’s and their future Hall of Fame reliever Rollie Fingers, a spot-starter that season. Bradley faced and shut out the division-winning A’s two more times that year.

After 14 starts, Bradley had a 1.67 ERA, second in the American League to Oakland’s Vida Blue. Tom attributed much of his success to pitching coach Johnny Sain. “I’m doing better because of the controlled breaking pitch that I learned from Sain. That gives me a pitch which is like a slider, that I can get over the plate,” he recalled.

Bradley’s success was getting attention throughout the baseball world. Baseball Digest profiled Tom in its August 1971 issue. In an interview with Dave Nightengale, Tom presciently stated “I’d like to coach college baseball someday, and wouldn’t it be something if I could go back to the University of Maryland to do it.”

During the remainder of the season, the White Sox bounced around several games under .500, though they finished strong, winning ten of 14 to close at 79-83, third in the AL West. They had improved by 23 wins over 1970. Bradley’s record stood at an even 15-15 for the year but he had done much to stabilize the rotation. He was tied for third in the American League in games started with 39, tied for fourth in shutouts with six, was sixth in innings pitched with 285 2/3, and sixth in strikeouts with 206–nearly three times as many as he walked.

Over the 1971-72 offseason, Hemond continued to look for trades to fuel the White Sox surge. On December 2, 1971, he swung two deals, sending infielder Rich McKinney to the Yankees for workhorse starting pitcher Stan Bahnsen; lefty starter Tommy John went to the Dodgers for slugger Dick Allen.

With both Wood and Bradley seeming to thrive on maximum work, Tanner and Sain flaunted baseball’s conventional thinking in 1972, using a three-man rotation of Wood, Bradley and Bahnsen, with rookie Dave Lemonds filling in for doubleheaders. Unproven but strong-armed newcomers Rich Gossage and Terry Forster were available if the team needed additional innings.

Bradley, Wood and Bahnsen held up their end of this arrangement admirably, starting 130 of Chicago’s 154 games; the Sox season had been shortened by eight games due to the April strike. Dave Lemonds started 18 games but pitched only 94 innings, requiring significant bullpen support.

Tom Bradley started the third game of the 1972 season for the White Sox on April 16 against the Kansas City Royals. He got a no-decision for his efforts as the Sox went on to lose 4-3, opening the season 0-3. In his second start, again against the Royals on April 22, he was the winning pitcher, going 8 2/3 innings in a 3-2 Sox victory. The five days of rest became a rarity for Bradley. Three days became the norm, and on seven occasions in 1972, Bradley started with only two days’ rest. In those outings, the White Sox lost six, with Bradley posting a 2-4 record despite a 3.19 ERA, only slightly above his overall season mark of 2.98.

One observer who scoffed at this White Sox “iron men” regimen was Ted Williams, manager of the Texas Rangers: “Some place along the line this summer Bradley and Bahnsen will show the effects. You can do it for only so long.”

But as the season progressed toward the halfway point, Chicago’s three-man rotation was showing remarkable success. In the second game of a doubleheader against the Twins on July 2, Bradley and Terry Forster combined for a three-hit, 2-1 victory; the win gave the White Sox a 41-28 record, good enough for second place in the American League West, 3½ games behind Oakland. Bradley, Wood, and Bahnsen had combined for a 32-21 record, 77 percent of the team’s decisions.

In the heat of July, however, Tom Bradley lost his next four decisions (two of those on two days’ rest) and the Sox dropped with him, falling to 7½ games back. The All-Star break arrived, and Bradley got to catch his wind, shutting out Kansas City, 5-0, on July 28. The win launched Chicago on a spurt as they won ten of their next 12 games. The Sox arrived in Oakland on August 10 only a game behind; Tom Bradley opened the four-game series against the A’s and Ken Holtzman. Bradley took a 2-0 lead into the seventh inning, but when the A’s put two men on base with two out, Chuck Tanner brought in Terry Forster. Forster got the side out but then gave up the tying runs in the eighth. Oakland eventually won the game 5-3 in the 19th inning. The White Sox fought back to split the series; they then won eight of the next ten games to pass the A’s and take over first place. Bradley started three of those games and the Sox won two. His record stood at 13-10.

But that’s as good as it got for the Sox. Exhausted from five months of unexpectedly being in a pennant race against the mighty A’s, the Sox hitters went cold in September and Tom Bradley lost three straight, never reaching the sixth inning. Chicago did remain competitive through September, winning 14 of the final 24 games. Bradley’s fortieth and last start of the year was a complete game win, 5-1 over the Texas Rangers on September 29.

In 1972, Tom Bradley was 15-14 with a 2.98 ERA. He pitched 260 innings, struck out 209 batters (fifth in the American League) with 7.235 strikeouts per nine innings (fourth). He became only the third pitcher in White Sox history, besides Ed Walsh and Gary Peters, to record two seasons with more than 200 strikeouts. Bradley had a retroactively calculated WAR of 4.9, eighth best among 1972 American League pitchers. WAR (“Wins Above Replacement”) is a Sabermetric method of judging a player’s value in wins to his team above what a replacement player might contribute to the same team. But as a practical matter with Tom Bradley and the ’72 White Sox, the team couldn’t find an adequate fourth starter for its rotation, let alone a replacement for one of the top three.

Hemond, still an active mover of personnel and looking for speed, power, and better defense, traded Bradley to the San Francisco Giants in the 1972-73 offseason. He went in exchange for outfielder Ken Henderson, once considered another “the next Willie Mays” and future Cy Young winner, albeit with Baltimore, pitcher Steve Stone. Responding to an inquiry about Bradley nearly 40 years later, Hemond recalled at the 2011 SABR convention, “But that was a good trade. If Henderson hadn’t been hurt [on May 25, 1974], we would have won the pennant.”

Bradley learned of the trade in the White Sox business office, preparing for his day’s work selling season ticket plans. Never lacking in humor (he had given his roommate, Rich Gossage, the nickname “Goose”) Tom remembered, “I come to work to sell tickets and before the cream was in my coffee I was in San Francisco.”

In San Francisco, the Giants were excited to have Bradley. They had finished in the first division for eleven consecutive years before falling to fifth in the six-team National League West in 1972. Much of this collapse was attributable to deteriorating pitching. The Giants had traded future Hall of Famer Gaylord Perry to the Cleveland Indians for “Sudden” Sam McDowell; in 1972, McDowell had won only ten games and was often shelved with a sore arm. In addition, the future Hall of Famer the Giants had kept, Juan Marichal, appeared to be aging rapidly. Marichal’s 18-11 log for 1971 had dropped to 6-16 in 1972. Tom Bradley, now 26, with all his quality innings, was acquired to ease the workload for Marichal, 35, and McDowell, 30, ideally allowing them to return to their winning ways. Manager Charlie Fox described Bradley as “a strong pitcher with excellent control, still maturing.”

Tom Bradley made his National League debut on April 8, 1973, against Cincinnati, losing 3-1. His first victory with the Giants came on April 12 when he went the route in a 9-3 victory over the Houston Astros. Five days later, Bradley started in a 15-2 romp over the Atlanta Braves. But during the fifth inning, Ralph Garr lined a ball off Bradley’s right ankle. Bradley managed to finish the inning and got the win, but didn’t return for the sixth inning. X-rays revealed a broken bone, and Tom was sidelined for four weeks.

As the season progressed, Bradley hovered around the .500 mark, but pitched a gem on August 25–a four-hit, 1-0, effort against the Mets and Tom Seaver, the last of Bradley’s ten major-league shutouts.

The ’73 Giants ended third, eleven games behind the first-place Reds, but 15½ games closer than they had been in 1972. Tom Bradley contributed 224 innings, despite the loss of starts caused by his ankle injury, and was 13-12. However, his 1973 ERA jumped by almost a run over 1972 to 3.90. His strikeout-to-walk ratio deteriorated from 3-1 to 2-1. As a result, he vowed to change tactics, telling The Sporting News the next spring, “I certainly don’t want to hit anybody, but I’ll just have to come into their kitchen more.” (If statistics are an indication, Tom Bradley rarely did pitch inside, hitting only ten batters in 1,017 career innings pitched.)

Ron Bryant, who had come out of nowhere to win 24 games in 1973 and establish himself as the Giants’ staff ace going into ’74, had injured himself in a swimming pool accident, so Bradley was named to open the season against Houston. And he did well, pitching into the ninth inning, picking up a 5-1 victory. By May 17, the Giants, 22-19, sitting third in the NL West, seven games out, were playing the San Diego Padres and losing 5-3 going into the ninth inning on a cold, rainy night in Candlestick Park. Bradley had started two days before, pitching adequately for five innings but still taking a loss. Giants’ manager Charlie Fox, who would be replaced by Wes Westrum later in the season, called on Bradley to finish the game. Tom was ineffective, giving up two runs that increased the San Diego lead. Worse, he felt pain in his pitching shoulder. “They asked me to pitch in relief, and like a dummy I said ‘yes.’ I felt something pop in my shoulder, and I wasn’t the same again.” Despite the condition, diagnosed as tendonitis, Bradley made his next scheduled start only two days later on May 19. He yielded five runs over seven innings, again against the Padres. The pain in the shoulder caused Tom to drop his arm while throwing; the changed mechanics led to a rotator cuff injury that would ultimately end Bradley’s career.

Bradley stayed in the rotation with pain and changed mechanics through the end of June. On July 4, he pitched a 9-2 complete game victory, defeating his frequent foes, the Padres. His record was 7-8; the Giants were 36-46, in fifth place. But the season was deteriorating, and so was Bradley’s status as a starter. Over the remainder of 1974 season, he made only four more starts, pitching 24 innings. He finished 8-11, 5.16, with 90 fewer innings than the year before; the Giants were 72-90 despite the midseason switch from Charlie Fox to West Westrum.

Bradley hung on with the 1975 Giants, but his days in the rotation were over. San Francisco considered releasing Tom since no other teams showed interest, but offered him the choice of pitching for their AAA club in Phoenix. On the plane ride to Phoenix he told columnist Art Spander “It was a blow to my ego, my pride. But I realized it could have been a lot worse. I couldn’t even get picked up on waivers. The Giants could have released me. But Mr. Stoneham was willing to stick with me. He was very good to me”.

Compiling a 5-3 record for Phoenix, Bradley was recalled for a start on June 29. He had one more excellent outing in his arm, pitching into the eighth inning in a 5-2 victory over the Dodgers and Don Sutton. He made his final major-league start on August 15, pitching four innings and losing, 9-4, to the Mets.

The following spring, the Giants had no plans for Bradley; on April 8, 1976, he was claimed off waivers by the Oakland A’s and assigned to their Tucson club in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League. There, Tom was part of the rotation, making 22 starts with a 6.51 ERA and 5-9 record. But these lackluster results in the same league where Bradley had seen better success only the year before convinced him his pitching career was over.

Pursuing the idea he had mentioned to reporters as a player, the 29-year-old Bradley looked for an opportunity in collegiate baseball. He spent a year as pitching coach at St. Mary’s (CA) College, and in 1979 became head baseball coach at Jacksonville (FL) University. There, he developed the school’s program over the next twelve years with a 431-291-1 record. He was inducted into the Jacksonville University Sports Hall of Fame in 1996. But Bradley had always wanted to return to his alma mater, Maryland, to coach, and in 1991 he took that opportunity when it opened for him. Tom Bradley was 243-306-5 as head baseball coach at the University of Maryland over ten years. The inevitable demands of big-time collegiate athletics, even baseball in the highly competitive Atlantic Coast Conference, claimed Bradley in 2000, when his contract was not renewed.

With a continued love for coaching and teaching, Bradley spent the next ten years in the minor- league systems of the Padres and Toronto Blue Jays, mostly as a pitching coach. His one venture into managing, in 2001, resulted in a 20-56 record with Toronto’s Rookie League Medicine Hat Blue Jays.

Tom had married Kathy Duff, a former Delta Airlines flight attendant, on October 26, 1974, before his last season with the Giants. They have two children, Alix, born in 1979, and Andy, in 1982. As of mid-2012, Tom and Kathy, a graduate of Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia, now retired from primary-school teaching, live in Barboursville, West Virginia, near Huntington. Tom continues to keep active in baseball, coaching the pitchers on the Gonzaga College High School (Washington, D. C.) team where Andy is head coach. Alix Simmons, the Bradleys’ daughter, is a buyer for Macy’s in San Antonio, Texas, and recently presented the Bradleys with their first grandchild.

Sources

The author relied on numerous articles from The Sporting News for this biography. Also of great help were interviews by Dave Laurila in Baseball Prospectus (October 29, 2008), Tom Owens in Baseball By The Letters (April 11, 2011), and Dave Nightengale in Baseball Digest (August 1971). Both the Jacksonville University and University of Maryland athletics websites provided useful information about Tom Bradley’s playing and coaching careers. The author is indebted to Gabriel Schechter (SABR) for accessing Tom Bradley’s player file at the Baseball Hall of Fame Library. As always, Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org were invaluable in providing statistics and game log information. The author interviewed Tom Bradley by telephone on March 14 and April 19, 2012, and talked with former White Sox general manager Roland Hemond at the 2011 SABR convention in Long Beach, California.

Full Name

Thomas William Bradley

Born

March 16, 1947 at Asheville, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.