Tom Cheney

“I didn’t like how my baseball career ended, particularly because I was so young. I won only 19 games total. But I realized how fortunate I was to have made it to the majors. Not many make it. And how many guys who played for many years didn’t get to play in the World Series or win a title? I also cherished the togetherness of players in an era when we didn’t make enough money for money to matter. So I got about as much out of the game as a person could ask for.” – Tom Cheney.1

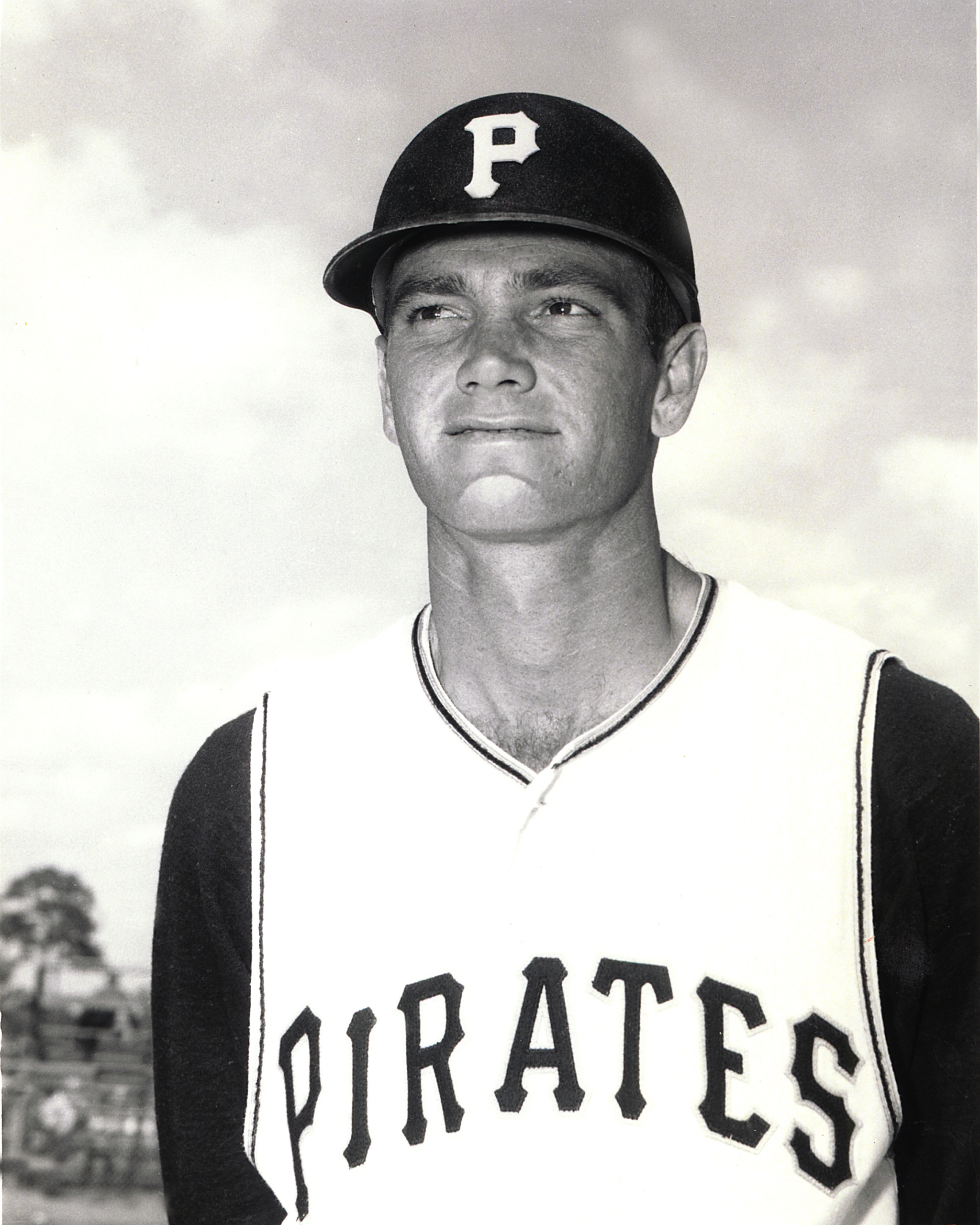

Tom Cheney was a proud and humble man, a true Southern gentleman, stubborn, strong-willed, a man’s man who loved outdoor life, farming, hunting, and fishing. A country boy to the core, he was far more comfortable in the confines of a duck blind than under the lights of a big city. His teammates good-naturedly called him Skins or Skinhead because of his premature baldness, but family and friends back home knew him by his full first name, Thomas.

Tom Cheney was a proud and humble man, a true Southern gentleman, stubborn, strong-willed, a man’s man who loved outdoor life, farming, hunting, and fishing. A country boy to the core, he was far more comfortable in the confines of a duck blind than under the lights of a big city. His teammates good-naturedly called him Skins or Skinhead because of his premature baldness, but family and friends back home knew him by his full first name, Thomas.

The Pittsburgh Pirates obtained Cheney, a minor-league pitcher at the time, from the St. Louis Cardinals on December 21, 1959, along with outfielder Gino Cimoli, in exchange for pitcher Ronnie Kline. After his recall from Columbus in midseason 1960, the Georgia native compiled a 2-2 record in 11 games, starting eight of them, and earned a spot on the World Series roster. Tom pitched three games in relief in the fall classic, posting a 4.50 ERA in four innings while striking out six.

Cheney’s stay in Pittsburgh was brief. After just one game with the Pirates in 1961, he was demoted to the minors and later traded to the Washington Senators. The hard-throwing right-hander blossomed into one of the American League’s most effective starters in 1962 and 1963, albeit amid the obscurity of pitching for a last-place club.

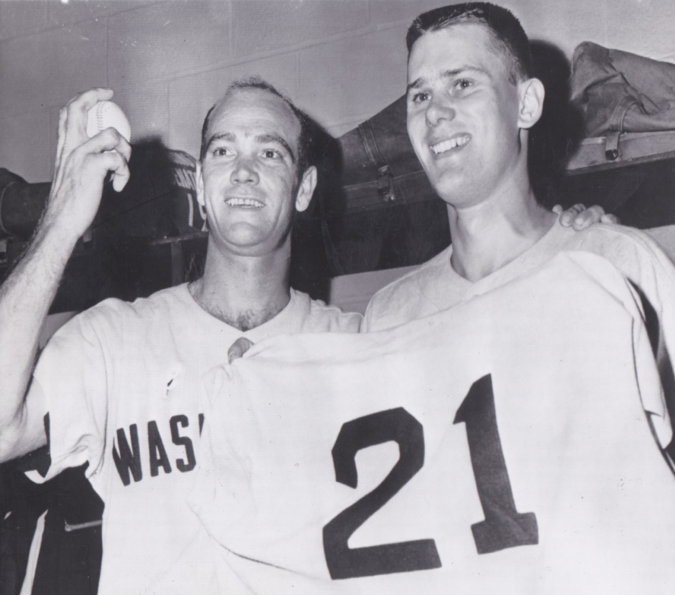

On September 12, 1962, Cheney stunned the baseball world and established a major-league single-game strikeout record, fanning 21 Baltimore Orioles in a 16-inning complete game in Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium. “For that one night,” Senators broadcaster Dan Daniels proclaimed years later, “he was as fine a pitcher as I ever have seen.”2

Cheney opened the 1963 season as the hottest pitcher in baseball. But just as he appeared to be on the verge of stardom and big paychecks, the 28-year-old was dealt a devastating blow. In the sixth inning of a game against the Orioles in July, he threw a pitch that tore up his elbow. He labored through just 63 more major-league innings before calling it quits in 1966. This cruel and sudden twist of fate ended a promising career, and the forgotten record-holder returned to Georgia to a life outside of baseball until his death in 2001.

Thomas Edgar Cheney, III was born on October 14, 1934, near Morgan, Georgia, about 200 miles south of Atlanta. Parents Ed (Thomas Edgar Cheney II) and Perk (maiden name Ollie Geneva Perkins) had inherited a parcel of the vast acreage owned by the first Thomas Edgar Cheney. Their peanut and dairy farm was one of the more prosperous in Calhoun County. Mr. Ed and Miss Perk appreciated the finer things in life, and exuded sophistication uncommon to the area. According to Cheney’s close friend Ted Jones, the well-furnished family home featured stained hardwood floors and Persian rugs, an unusual elegance. Mr. Ed drove a sharp automobile, and Miss Perk outfitted Thomas in the most beautiful store-bought shirts, not the plain-sewn homemade clothing worn by most farm kids.3 Nonetheless, Thomas and his younger brother, Charles, experienced the rigors of farm life growing up. “I remember my Daddy telling me that he would have to get up early in the morning and light the fires and get things going before his parents got up,” recalled Terri Cook, Cheney’s elder daughter.4

Thomas pitched and played shortstop in American Legion and high-school baseball. After graduation, he enrolled in nearby Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College, a two-year institution at that time, with the idea of becoming a veterinarian. He helped lead the Stallions to the state junior-college championship in 1952.5 Only 18 years old, he stood 5-feet-11 but weighed a scrawny 150 pounds. Still, he was impressive enough to interest major-league scouts. The mound prospect traveled to Atlanta to audition with the Boston Braves before accepting a $1,500 bonus from scout Mercer Harris to join the St. Louis Cardinals’ Class D affiliate in Albany, Georgia, close to home.6

Moving up to Class C Fresno in 1954, the 19-year-old won 12 games and struck out 207 California League batters in 203 innings. He also met Jackie Bennett, a 16-year-old beautician school student, at a burger drive-in. That summer, a romance flourished, and Jackie was heartbroken when Tom went home to Georgia at the end of the season. Immediately after her 18th birthday on May 29, 1955, the lovestruck young lady drove by herself from California to the Cheney farm near Morgan. Tom was pitching for nearby Class A Columbus at the time. On June 9 the young couple exchanged vows in the family living room.7

Cheney matriculated steadily through the abundant St. Louis farm system. The newlywed had a good season at Columbus in 1955, and excelled at Triple-A Omaha in 1956 and 1957, where he was among league leaders in ERA and voted to the American Association All-Star team both years. His stellar performance earned him an invitation to the Cardinals spring-training camp in 1957, and St. Louis skipper Fred Hutchinson named him to the club’s Opening Day roster.8 Cheney hurled four shutout innings in his big-league debut, but wildness overcame him in subsequent games. After walking 15 batters in just nine innings, the rookie was optioned back to Omaha.

“At the time, I could throw hard but my control was off and on, like it would be my entire career,” Cheney told author Danny Peary.9 He threw mostly fastballs, but also had a good curve, and learned how to throw a knuckleball from Cardinals teammate and future Hall of Fame pitcher Hoyt Wilhelm. Later, Cheney added a slider and screwball to his pitching repertoire. “I’ll throw a screwball to left-handed hitters, but it’s more of a change than a real scroojie,” he said.10 One pitch he tried to learn in Pittsburgh but could not master was Elroy Face’s forkball.

Cheney would have returned to the Cardinals as a September call-up, but was drafted into military service. He reported to Fort Jackson, South Carolina, on September 10, 1957, for basic training. From there, Cheney was assigned to Fort McPherson, Georgia, and helped lead the base team to its fourth straight 3rd Army championship in 1958.11 On April 27, 1959, Jackie gave birth to the couple’s first child, daughter Terri Lynn. A month and a half later, the new father was mustered out of the Army. He rejoined the Cardinals on June 16, but struggled to regain his control. In 112/3 innings he surrendered 17 hits and 11 bases on balls, and was demoted back to Omaha.

The Cardinals sent Cheney to Havana, Cuba, to play winter ball. “My wife and 8-month-old daughter came with me,” he recalled. “We got $350 a month in expenses to go along with my $1,500-a-month salary. It was a life of luxury. We had a nice home, with a maid from the Virgin Islands, and had access to the yacht club and country club. We played just four games a week.”12 It was in Cuba that the young hurler learned he had been traded to the Pirates along with Gino Cimoli for Ronnie Kline.

Pittsburgh faithful scratched their heads, wondering why general manager Joe L. Brown would swap Kline, a durable starter, for Cimoli, a fourth outfielder they seemingly didn’t need, and Cheney, a raw and wild hurler totally unimpressive in two abbreviated stints with the Cardinals. As spring training of 1960 unfolded, sportswriter Arthur Daley of the New York Times concluded that Bing Devine had shrewdly pilfered the clueless Brown and pulled off an epic heist, proclaiming that “this trade may be the biggest steal since the Brinks robbery.”13 Brown countered at a press luncheon at Forbes Field that “the Pirates can win the pennant – if they want to” and that “Cheney may surprise.”14 As it turned out, both Cimoli and Cheney contributed to Pittsburgh’s pennant-winning season while Kline was a major disappointment in St. Louis.

Pittsburgh faithful scratched their heads, wondering why general manager Joe L. Brown would swap Kline, a durable starter, for Cimoli, a fourth outfielder they seemingly didn’t need, and Cheney, a raw and wild hurler totally unimpressive in two abbreviated stints with the Cardinals. As spring training of 1960 unfolded, sportswriter Arthur Daley of the New York Times concluded that Bing Devine had shrewdly pilfered the clueless Brown and pulled off an epic heist, proclaiming that “this trade may be the biggest steal since the Brinks robbery.”13 Brown countered at a press luncheon at Forbes Field that “the Pirates can win the pennant – if they want to” and that “Cheney may surprise.”14 As it turned out, both Cimoli and Cheney contributed to Pittsburgh’s pennant-winning season while Kline was a major disappointment in St. Louis.

Cheney began 1960 in Triple-A Columbus, Ohio. After two months, his record stood at just 4-8, but he had regained his control and was leading the International League in strikeouts.15 The Pirates recalled him on June 28. The balding right-hander notched his first major-league win on July 6 at Cincinati, and his first big-league shutout on July 17, a four-hitter against the Reds at Forbes Field. Cheney stayed with the Pirates the remainder of the season, appearing in 11 games as a spot starter and reliever. He finished with a 2-2 record and 3.98 earned-run average in 52 innings pitched. In the 1960 World Series Cheney saw action in the three blowout victories by the Yankees. In four innings of work he struck out six batters, including Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle. But he also surrendered the triple to Bobby Richardson that broke open Game Six for the Bronx Bombers.

“When I got to Pittsburgh, I discovered I wasn’t just on a great team but got to play with a great bunch of guys,” Cheney reminisced. “It wasn’t cliquish at all. … Any 5 to 10 of us would go out together after games. Stars and non-stars, it didn’t matter. I was in only 11 games, 8 as a starter. Yet this team was so tight that I was voted a full World Series share. They accepted me.”16

Although the 1960 season ended on a promising note for Cheney, 1961 proved to be excruciating painful. He made the Pirates’ 28-man Opening Day roster but pitched poorly in his first relief appearance, in Los Angeles on April 16. Failing to record an out, he surrendered five runs on four walks, an error, and a home run by light-hitting catcher Norm Sherry. With the May 10 deadline looming to reduce the major-league roster to 25 players, Tom received a shocking phone call from home – father Ed Cheney had died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of 52.

Tom flew home to Morgan to help his widowed mother and brother, and then called general manager Joe Brown. “It was approaching the cutdown date for rosters, and I knew it was between me and pitcher George Witt to go,” he recalled. According to Cheney, Brown gave his word that he would be retained. Upon his return to Pittsburgh, however, Brown informed him that he was being sent down to Columbus. “I cursed him terribly, calling him everything a man can be called. I could have handled the truth, but don’t lie to me. That was the worst thing that ever happened to me in baseball,” Cheney fumed. “I never forgave Brown. I told him that ‘the best thing you can do for me is to get me out of this whole organization, because I’ll never play for you again.’”17

“He was very tender and loving,” Terri noted, illuminating her father’s code of ethics, “but he was also a very firm man. He was the kind of man that you don’t need anything in writing, you just do what you say you’re going to do. That’s pretty much how life was down in South Georgia anyway – you’re honorable; you do what you’re supposed to do.”

Brown granted Cheney his wish on June 29, 1961, swapping him to the expansion Washington Senators for veteran pitcher Tom Sturdivant. The trade reunited Cheney with former Pirates coach Mickey Vernon, now the Senators manager. But misfortune continued to dog the right-hander. A ribcage injury sidelined him for six weeks. Overall in 1961, he walked 30 batters in 29 2/3 innings and surrendered nine home runs, including number 54 to Roger Maris, who broke Babe Ruth’s single-season home-run record that year.

Coming into spring training with the Senators in 1962, Cheney’s career major-league pitching log was ugly. Of 20 starts, he had failed to pitch past the fourth inning in 14, and he averaged nearly eight walks per nine innings. But manager Vernon had faith that Cheney would come around, and he did. He began the 1962 season in the bullpen, but joined the Nats’ starting rotation in mid-May. By the end of the year Cheney had pitched 1731/3 innings, hurled three shutouts, and posted an ERA of 3.17, seventh best in the American League. His control improved and he struck out 147. He was second in the American League in strikeouts per nine innings, and held right-handed batters to a measly .188 batting average.

On September 12, 1962, Cheney hurled a 16-inning complete-game 2-1 victory in which he struck out 21 batters, more than any other major-league pitcher before or since. As a reward for his record-breaking performance, Senators president Pete Quesada gave Cheney a $1,000 bonus. “They had cut my salary a thousand dollars after the 1961 season,” Cheney reasoned, “so I didn’t consider it a bonus but just getting back what they owed me.”18

Cheney began the 1963 season on fire. Armed with a nasty repertoire of pitches – a crackling fastball, tumbling curve, slider, screwball, and knuckler – and aided by a rule change that expanded the strike zone, Cheney posted four straight complete-game victories and surrendered only one earned run for a 0.25 ERA.19 By the All-Star break, he sported an 8-9 record with four shutouts, a 2.88 ERA, and an excellent WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) of just 1.04 for a woeful Senators team that was 30-56 and last in the league in batting, pitching, and fielding. “Cheney acquired the last thing he needed to be a sensational pitcher – control,” observed rival manager Bill Rigney of the Los Angeles Angels.20

Cheney also seemed to have conquered another nemesis – extreme nervousness. “It was a tough life being a ballplayer,” confided the moundsman years later. “You were always under pressure even if you weren’t in a pennant race. You never forgot that if you didn’t do the job, there was someone in the minors who was waiting for you to fail or be injured.”21 Reserve infielder Dick Schofield was a good friend of Cheney’s dating back to their days in the Cardinals farm system. “Skinhead had a great arm and threw a great curve,” Schofield recalled, “but when he came to Pittsburgh he was still trying to stick in the majors. He was always nervous. He’d light one cigarette right after another.”22 Senators coach Rollie Hemsley felt Cheney was mishandled in 1962. “They should have helped Cheney to forget that he is a nervous pitcher, instead of reminding him of it.”23 Good friend Ted Jones speculated that Tom’s rural upbringing contributed to his anxiety. “I think he felt pressure coming from where we all came from and the backgrounds that we had. Thomas was not a big-crowd guy. He was kind of shy. I think that he felt the pressure of the crowd and the fans and the big league players.”

Cheney appeared to be ascending to the pitching elite in 1963 when, working on yet another shutout on July 11, he suddenly felt something snap in his elbow. “I threw a pitch and it felt like someone had a knife and ripped me down the forearm,” he recalled.24 Cheney pitched just five more games that year, totaling nine innings. In his final start of the season, on August 26, he faced just five batters before his sore elbow forced him out of the game.25 The diagnosis was an elbow strain, further defined as epicondylitis, or “tennis elbow” in layman’s terms. The only prescription was rest and physical therapy.

The following spring, given a clean bill of health by the Senators’ club physician, Dr. George Resta, Cheney opened the 1964 season in the Nats’ starting rotation. Gil Hodges had replaced Vernon as manager the previous midseason, and Cheney didn’t get along with his new boss. “I wasn’t his favorite person and he wasn’t mine,” the right-hander conceded.26 Winless in four starts, Cheney was demoted to the bullpen. “I kept trying to pitch but couldn’t take the pain for more than four or five innings. By that time my elbow would start swelling. I could have gone up to three innings without much trouble, but Hodges said that he wanted me to start.”27 Cheney pitched in short relief for nearly a month, but was called upon by Hodges on June 9 to start the second game of a doubleheader against the Kansas City Athletics. The tough hurler battled through pain to earn a 5-1 complete-game win. “He kept me out there much too long,” Cheney said decades later. “I stayed out there throwing until tears were coming out of my eyes. Afterward I was sitting in front of my locker. Hodges walked by and said, ‘Thataway to go.’ I said, ‘Yeah, you son of a bitch, that was the last game I’ll ever pitch.’ ”28 The victory was the 19th and last of Cheney’s abbreviated career. He made one more mound appearance, five days later, and then was sent to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. The injured pitcher was ordered to take nine months to a year off to give his torn elbow muscles time to heal. Cheney missed all of the 1965 season and attempted a comeback in 1966, but after three games was demoted to the minors and ended his career ingloriously in Double-A York of the Eastern League. At about the same time, on July 20, 1966, Cheney’s life took on added responsibility; Jackie gave birth to their second daughter, Lacie Ann.

“It was hard to accept,” the mothballed pitcher, just 31 years old at the time, said years later. “I had an exceptionally good start in 1963. It’s hard to go out and redo your life. It’s hard to leave something you really love. There was a big cut in salary for one thing.”29 The premature end to his baseball career proved to be exceedingly difficult for Cheney. “What you have to understand is that his life was taken away from him,” daughter Terri reasoned. Her father returned to Morgan to help out on the family farm, but succumbed to the demons of alcohol abuse. To protect their daughters, Jackie filed for divorce in 1969. She remarried in 1971. Tom also remarried, and divorced, twice during the ensuing two decades.

In 1987, at Terri’s wedding, Tom and Jackie reconnected, and two years later, the first Mrs. Cheney also became the fourth. “When they got married a second time, there was such peace between the two of them,” said Terri of her parents. “She always told me, from the very first time she met him, her stomach would just flutter and that she still felt that way every time she looked at him, even when they were divorced.”

A heavy smoker nearly his whole life, Tom eventually suffered from emphysema. He finally quit smoking, as did Jackie. Over the years, Tom and his brother Charles bought a fertilizer plant, and then got into the propane-gas business. When he sold his share of the company, Tom stayed on as one of their delivery-truck drivers. He finally retired when he couldn’t fill out the paperwork anymore. It was the early onset of Alzheimer’s disease, which had also afflicted his mother, Miss Perk. The disease finally took the life of Thomas Edgar Cheney, III on November 1, 2001. Ten weeks later, Jackie Cheney died from melanoma cancer.

On the surface, Tom Cheney’s career pitching line is mediocre at best. His 19-29 won-loss record is unimpressive. Yet of his 19 wins, eight were shutouts. When Cheney was on his game and healthy, he was dominant. Such was the case on the evening of September 12, 1962, when the determined young right-hander struck out 21 batters in a single major-league game.

Only 4,098 fans showed up at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore that Wednesday night to witness the game between two second-division ballclubs. The 27-year-old Cheney felt good warming up, and was staked to a 1-0 lead early. He recorded his first strikeout in the second inning, and struck out the side in the third and fifth. The Orioles finally broke through, however, to tie the score in the seventh. After nine innings, Cheney had recorded 13 strikeouts, but the futile Senators had managed only four hits and the game stood even at 1-1. Cheney continued to carry the team on his back. After 11 innings he had chalked up 17 strikeouts but the game remained tied.

By the 12th inning, manager Vernon wanted to take Tom out, but he insisted on staying in. “I said I wanted to win or lose it,” Cheney recalled. “He never mentioned my coming out again.”30 It was not the first time the determined right-hander had gone deep into extra innings. In an American Association playoff game in 1959, for example, he pitched into the 12th inning against Minneapolis before losing 3-2.31

With one out in the bottom of the 14th, Cheney chalked up victim number 18, and over the Memorial Stadium public-address system it was announced that he had tied the modern major-league record, held by Sandy Koufax, Warren Spahn, Bob Feller, and Jack Coombs. “I was surprised. I thought it was more like 13 or 14,” Cheney said after the game.32 Distracted, he threw two pitches high to the next batter, pitching adversary and former outfielder Dick Hall, then regained his composure to fan Hall for his 19th strikeout and a new modern record.

Cheney racked up his 20th strikeout in the 15th inning, breaking the all-time record set by Charlie Sweeney and Hugh Daily in 1884, when rules were much different. But it was getting late. Baltimore’s curfew law prohibited any inning from starting after midnight.33 It became apparent that the 16th inning would be the contest’s last – win, lose or tie. Fortunately for the Senators, first baseman Bud Zipfel hit what would become the last home run of his short major-league career. Cheney took the mound in the bottom of the 16th inning with a one-run lead and yielded a one-out single. Incredibly, it was the first Oriole hit Cheney had allowed since the eighth inning! He retired Jackie Brandt on a fly to center, and then faced the dangerous Dick Williams, a .419 pinch-hitter that season. With the game on the line and 11:59 p.m. on the clock, Cheney caught the future Hall of Fame manager looking for his 21st strikeout and a hard-earned 2-1 victory.

Cheney threw 228 pitches that night, fueled by adrenaline and chain-smoking between innings. “That game he must have gone through three packs of cigarettes,” recalled teammate Chuck Hinton.34 “I sat down in the locker room afterward,” Cheney reflected, “and in 15 minutes I was exhausted. The tension had worn off. I didn’t realize I was that tired.”35 Teammate Don Lock remembered the drive back to Washington after the game, when Cheney began suffering muscle cramps. “Legs, stomach, back, and arms,” recalled Lock. “In all honesty, he should have been on a sugar IV drip.”36

Batterymate Ken Retzer described what it was like catching Cheney that game. “That curveball of his looked like it was falling off the table. Tom was getting a lot of the hitters out with screwballs, too, and he came in with his knuckler now and then and was getting it over.” Baltimore hitters were duly impressed. “He had great stuff,” vouched Russ Snyder, a three-time strikeout victim. “I never saw a better curveball.”37 “He showed me the greatest stuff I’ve seen from any pitcher,” said future Hall of Famer Brooks Robinson.38 Jackie Brandt felt that Cheney was more formidable than Sandy Koufax, whom he had faced in the left-hander’s 18-strikeout game in 1959: “Koufax wasn’t that sharp. I don’t think Sandy would have struck out 21 in 18 innings. Cheney’s curveball was falling out of the sky.”39

The record-setting masterpiece thrown by Cheney on September 12, 1962, is impressive, but rarely mentioned. The shy, reclusive record-holder returned to Baltimore at the Orioles’ invitation in 1992 to mark the game’s 30th anniversary, and attended only a few autograph sessions over the years.40 His last public appearance was at a Washington Senators reunion on February 26, 2000. By that time, Alzheimer’s was beginning to take its toll.

Throughout the years, Tom Cheney was always humble about his strikeout record, never one to indulge in self-promotion. He always felt that he was merely doing his job. The fact that it took 16 innings for Cheney to set the record has worked against him, invalidating the achievement in many of baseball’s record books.

“Well, I’m very proud of him,” exuded Cheney’s daughter Terri. “It’s a record that hasn’t been broken. Other people can say anything they want, but nobody has broken it yet. When I think back on him, I think about his determination. And, yeah, he had some issues and stumbles along the way. But the man he was and the determination he had – to do something like that – I’m very proud of it, proud of him. In my eyes, he’s just a great man.”

This biography is included in the book “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2013), edited by Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Sources

Interviews with Terri Cook, November 6, 2011, and Ted Jones, January 14, 2012. The author is deeply grateful for their time and recollections.

Baseball Digest, May 1974 and April 1986

Google archives

Peary, Danny, We Played the Game (New York: Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers, 2002).

New York Times

Washington Post

The Sporting News, 1956-1966.

Notes

-

Danny Peary, We Played the Game (New York: Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers, 2002), 556.

-

Carl Lundquist, “Dapper Dan Labels White Seat Symbol of New Traditions,” The Sporting News, August 27, 1966, 16

-

Interview with lifelong friend Ted Jones, January 14, 2012. All subsequent quotes from Mr. Jones are taken from this interview.

-

Interview with daughter Terri Lynn Cheney Cook, November 6, 2011. All subsequent quotes from Ms. Cook are taken from this interview.

-

Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College website (www.abac.edu). In 2008 Cheney was named to the college’s Athletics Hall of Fame inaugural class.

-

Peary, 181.

-

Bill Turque, “Q: Which Washington Senators pitcher set the all-time record for strikeouts in a single game?”, Washington Post Magazine, June 22, 2008, 19.

-

Bob Broeg, “Kid Cheney Climbs in Card Hill Ratings as Mizell Tumbles,” The Sporting News, April 17, 1957, 23.

-

Peary, 356.

-

Bob Addie, “Ex-Bucs Cheney, Leppert Fill Bill in Capital,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1963, 9.

-

“Cheney, Owens – Stars in Army Title Tourneys,” The Sporting News, September 24, 1958, 45.

-

Peary, 429.

-

Arthur Daley, “An Unexpected Gift,” New York Times, March 25, 1960, 32.

-

Les Biederman, “Pirates Can Win by Showing They Want To – Brown,” The Sporting News, January 20, 1960, 9.

-

The Sporting News, July 6, 1960, 37.

-

Peary, 473. It is noted that this contradicts the November 2, 1960, edition of The Sporting News, in which it was reported that Cheney had been voted a half-share.

-

Peary, 509.

-

Robert C. Gallagher, “Tom Cheney: He Fanned 21 Batters in a Single Game!”, Baseball Digest, April 1986, 91.

-

Had it not been for an unearned run surrendered in the second game, Cheney would have thrown 321/3 scoreless innings to start the 1963 season, an American League record. The major-league record as of 2012 was 39, set by Brad Ziegler for the 2008 Oakland A’s.

-

Shirley Povich, “Nat Fans Flip Over Cheney, Ace Chucker,” The Sporting News, May 4, 1963, 20.

-

Peary, 577.

-

Peary, 471.

-

Shirley Povich, “Hemsley Tosses Barb at Nats for Mound Strategy,” The Sporting News, December 1, 1962, 25.

-

Peary, 582.

-

Adding insult to injury, daughter Terri was struck by a foul ball in the stands and required first aid. The Sporting News, September 7, 1963, 16.

-

Peary, 582.

-

Peary, 583.

-

Peary, 614.

-

Gallagher, 93. Cheney’s highest salary in baseball was approximately $15,000.

-

Peary, 555.

-

The Sporting News, September 23, 1959, 44.

-

Emil Rothe, “When Tom Cheney Fanned 21 Batters,” Baseball Digest, May 1974, 77.

-

Turque, 28.

-

Gallagher, 92.

-

Ibid.

-

Turque, 28.

-

Bob Addie, “Cheney Spins Whiff Magic With Crackling Curve Ball,” The Sporting News, September 22, 1962, 25.

-

Shirley Povich, “Nats May Offer King Slab Stars for Big Socker, The Sporting News, September 29, 1962, 7.

-

Bob Addie, “Tom Cheney’s Curve Was ‘Falling Off a Table,’ ” Washington Post, September 14, 1963, D7.

-

An impostor would occasionally show up at autograph events and claim to be Cheney. The family learned of this shortly before Cheney’s death, but chose not to pursue criminal charges.

Full Name

Thomas Edgar Cheney

Born

October 14, 1934 at Morgan, GA (USA)

Died

November 1, 2001 at Rome, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.