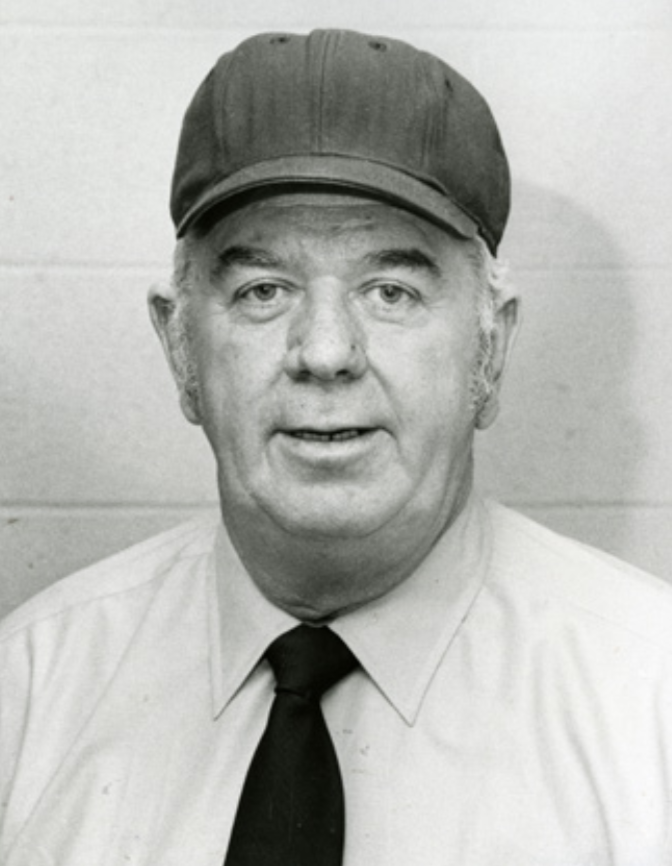

Tom Gorman

“When I go, I want to be buried in my umpiring suit, holding my indicator.”1

“When I go, I want to be buried in my umpiring suit, holding my indicator.”1

When Tom Gorman died, his children carried out their father’s final desire. Gorman was dressed in his suit, which was meticulously buttoned, and wore his blue cap with the white “NL” embroidered on the front of it. He also held his indicator in his hand. It was set at “3 and 2.” Just like the title of their father’s memoir.

Thomas David Gorman was born on March 16, 1919, in New York City. He grew up in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood, at that time considered the bastion of poor, working-class Irish. The neighborhood is mentioned prominently by Damon Runyon in his stories. Gorman was of Irish heritage and was actually born an hour before St. Patrick’s Day.

Hell’s Kitchen was considered a rough neighborhood, but Tom felt that it was a nice place to grow up. The Gormans were from County Cork, as Irish as a family could get. Both of his grandfathers emigrated from Ireland. His grandfather, Francis O’Gorman, and two of his sons were police officers. Francis, at the age of 47, died falling off a roof while chasing a prowler. Francis had three sons, Tom, David Francis (Tom’s father), and Vinnie. (O’Gorman was the original family name; the “O” was lost along the way.) Tom’s mother was Katherine (Moran) Gorman; her family came from County Mayo. Tom had two sisters, Helen, and Mary.

Tom’s father, David Francis, was a huge baseball fan, especially of the New York Giants. He gave his son his first glove, a Carl Hubbell model with short fingers. David Francis took his son to watch the Giants, and the Yankees. Tom’s favorite player was Lou Gehrig, while Bill Terry was his dad’s.

Tom’s baseball career road map developed early. He loved sports but his allegiance was divided between baseball and basketball. Tom was 6-feet-2 and played center in basketball at Power Memorial High School, just like a later graduate, Lou Alcindor, who was later known as Kareem Abdul Jabbar. Gorman went on to play 13 years of professional basketball, in the Pennsylvania State Pro League, the New York State Pro League, and half a season for the Toronto Huskies of the Basketball Association of America, one of the forerunners of the NBA.2

Gorman was fond of basketball. Aside from playing, he also coached and refereed. Although he loved basketball, some of his biggest successes were on the diamond during high school. Tom pitched on Power Memorial’s city championship teams in 1936 and 1937. Along with teammate Pancho Snyder, he threw batting practice for the Giants at the Polo Grounds.3

Gorman impressed Bill Terry and the Giants manager wanted to sign him. He could not wait to tell his father because his dad was a big fan of the former Giants great.

“Well,” Tom told his father, “Bill Terry would like to see you tomorrow morning around ten, ten thirty.” Terry gave Tom’s father a cigar and told him how fine a boy his son was, and a good athletic specimen. Tom’s father told Terry that he was a fan of his, and agreed to let Tom sign with the Giants.4 The Giants gave him a signing bonus of for $500. After two years in the minor leagues, Gorman’s major-league playing career consisted of five innings over four games at the end of the 1939 season as a 20-year-old. He gave up four runs, walked one, struck out two, and threw one wild pitch. He was hitless in his one at-bat; he handled his two fielding chances successfully.

Gorman was back in the minors in 1940. He was drafted into the US Army in 1941 and didn’t return to professional baseball for four years. Gorman underwent training at Fort Dix, New Jersey, and Fort Meade, Virginia, before ending up at Camp Stoneham in San Diego. Unlike many other former players, he did not play baseball while in the service. Gorman was a sergeant in the 16th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Division, and fought in the North African campaign. Before being discharged, he organized service teams. On September 17, 1945, Gorman’s father died suddenly.

Gorman proposed to Margaret Fay during a game between the Giants and Cincinnati Reds at the Polo Grounds. They were married in October 1945.

In 1946, while Gorman was in Winter Haven, Florida, for spring training, calcium deposits were discovered, and he developed a sore shoulder. He tried to keep it a secret, but because of his ineffectiveness the Giants traded Gorman to the Boston Braves.

Boston Braves manager Billy Southworth told him, “The way you’re throwing right now, well, maybe your arm will come around. You’ve got a chance. Maybe we’ll send you to the Eastern League.”5 The Braves management did decide to send him to the Eastern League.

Around this time Gorman was approached by the Pasquel brothers, who were raiding the major leagues for talent for the Mexican League. They offered him $8,000 to sign, and a contract for $12,000 over three years. He discussed his situation with Billy Southworth; the Braves agreed to give him his release.

Gorman, the only American on his team, experienced some success in Mexico. He had a 7-3 record his first year. But the Pasquels lost a lot of money that first season. They cut players’ contracts in half and made players had to pay their own expenses for the 1947 season. Gorman got $6,000 for his second season. He lost his first two starts, his shoulder began to feel worse, and he returned to the United States.

Once back, Gorman coached, officiated, and played basketball. He did not return to playing baseball. He did not even consider himself to be Class-D material.

One night after he refereed a basketball game between St. John’s and Holy Cross at Madison Square Garden, Neil Mahoney, a scout for the Red Sox, came into Gorman’s dressing room and made him two job offers: to either manage one of Boston’s farm teams or to umpire in the New England League. Gorman did not feel like umpire material. Mahoney disagreed; he felt that Gorman was the right size, possessed the right temperament, and knew the game. Although Gorman turned Mahoney down, the idea intrigued him. After thinking it over, Gorman informed Mahoney that he was interested.

Gorman met Claude Davidson, the president of the New England League, who told him that if he had a car, the job was his for $180 a month. Gorman was not exactly excited; he replied that it was not a lot of money. Gorman felt that he could make more selling newspapers. Neil Mahoney told Gorman that all of the leagues started their umpires out this way. Gorman’s wife asked him to try it for a year. He agreed and soon he signed a contract for $180 a month and $55 in expenses for the1947 season.

Gorman’s first partner was Dave Clary, from Brockton, Massachusetts. Their first game was in Nashua, New Hampshire, where Walter Alston was the manager of the Nashua Dodgers and Don Newcombe, Roy Campanella, and Joe Black were players. Clary worked the plate, Gorman the bases. Clary gave positioning advice to his partner; he asked Gorman where he umpired last.

“Dave, I’ll tell you the truth. I’ve never umpired a game in my life.”6

Gorman was behind the plate for his second game, with Don Newcombe pitching. It was a quiet night for both sides. So Clary, his partner, asked, “You sure you never umpired before?”7

Gorman’s first rhubarb was with George Kissell, the manager at Lawrence. By the original account, the game was Gorman’s first ejection as an umpire.

It did not take long for Gorman to make the major leagues. The National League purchased his contract from the International League and he made his debut on September 11, 1951, in Chicago. He was the third-base umpire that day, working with Al Barlick, Lee Ballanfant, and Augie Donatelli. He thought they were three of the best.

Gorman made his first mistake during that first big-league game. A batter popped up near the Cubs dugout and the third baseman made the catch on a slab of concrete next to the bat rack. Gorman signaled no catch. In the International League, concrete was not a part of the playing field; this was not the case in the majors and Ballanfant corrected him.

Throughout Gorman’s career he often was associated with Leo Durocher. He first met Durocher during the 1951 season when Leo was managing the Giants. Their introduction was initiated by a play at second base. Gorman called a baserunner out. Durocher came charging out to argue the call. Gorman, who had a propensity to embellish the truth in order to make a story entertaining, said this is what happened next: Durocher said, “Hey kid, I want to tell you something. You called the play too quick.”8 Gorman stood his ground and informed Leo that the runner was out. Durocher walked back to the dugout for about five or six steps and then made a U-turn. He got into rhubarb with Gorman, calling him a SOB, but since he did not get in the umpire’s face, Gorman would not eject him. In Three and Two, his memoir, Gorman recalled that a week or so later, his crew was in Brooklyn for a series between the Dodgers and Giants. According to Retrosheet, Gorman’s crew never went to Brooklyn until May 4, 1952. Gorman tossed Durocher out of the game at Ebbets Field. He told Durocher it was retribution for the game in the Polo Grounds. Gorman said Durocher became his first ejection in the majors. In reality, Durocher was not one of Gorman’s 27 career ejections. Durocher enjoyed getting into rhubarbs before a sellout crowd, especially a nationally televised game, and he played to the fans, which they loved. Gorman played along, although he did not throw out a lot of guys. The Durocher/ Gorman routine later became popular in Miller Lite beer commercials and on the banquet circuit. Gorman’s 27 career ejections are the least of any umpire who has worked at least 3,000 major-league games.9 (His last ejection was Ron Cey of the Dodgers, for arguing a third strike.)

Gorman retired as an umpire in 1976, and worked for a while as an umpire supervisor for the National League. Someone once asked him if he was ever wrong. “No, I’m never wrong. I can’t be wrong on my job,” he replied. “But I’ve made mistakes. I am a human being. I could be wrong, but when I call a play that’s the way I see it.”10

If one umpires in the National League for 25-plus years, as Gorman did, one undoubtedly officiates in many meaningful games. Gorman umpired in five World Series: 1956, 1958, 1963, 1968, and 1974. He was stationed on the left-field line during Don Larsen’s perfect game against Brooklyn in the 1956 World Series, and he was behind the plate when Bob Gibson struck out 17 Detroit Tigers during the first game of the 1968 World Series.

Gorman worked the 1971 and 1975 NLCS. He was the crew chief in 1971. He umpired the playoff between the Los Angeles Dodgers and Milwaukee Braves in 1959 to determine who was going to the World Series. He umpired in five All-Star Games: 1954, 1958, both games of 1960, and 1969.

Gorman umpired nine no-hitters, tying a NL record. He was behind the plate for Warren Spahn’s no-hitter in 1960 and Bill Stoneman’s in 1969.

Among Gorman’s honors were being named the Outstanding Umpire of 1974 and the Umpire of the Half Century by the Al Somers Umpire School. In 1970 he received the Bill Slocum Award from the New York chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America.

Gorman enjoyed being an umpire, but there were difficult managers. Leo Durocher and Fred Hutchinson were two who he felt were the most difficult. Bobby Bragan was always looking for loopholes in the rule book. There were several good-guy managers in his opinion, like Gil Hodges, Walt Alston, and Danny Murtaugh. He particularly appreciated ballplayers Bill Mazeroski, Roberto Clemente, Pee Wee Reese, and Dick Allen.

Gorman and his wife, Margaret, had three sons, Tommy, Brian, and Kevin, and a daughter, Patty Ellen. (Brian also became a major-league umpire, starting in the National League in 1991 and still active in 2016.) Margaret died in 1968. In July of 1986 Gorman remarried. His time with his new wife, Olga, was brief. He died of a heart attack on August 11, 1986, in Closter, New Jersey, at the age of 67. He is buried in the George Washington Memorial Park in Paramus, New Jersey.

In his acceptance speech for being named Outstanding Umpire of 1974 by the Al Somers Umpire School, Tom Gorman said, “People may come to see ballplayers, but there’d be no baseball without good umpires.”11

This biography is included in “The SABR Book on Umpires and Umpiring” (SABR, 2017), edited by Larry Gerlach and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

Holtzman, Jerome. “Never Missed a Call,” Chicago Tribune, August 17, 1986.

O’Connell, Jack. “Umpire Gorman to Make Shea History,” MLB.com, September 28, 2008.

Notes

1 Ira Berkow, “Tom Gorman’s Final Call,” New York Times August 17, 1986.

2 “Queen city cagers set for pro debut,” Montreal Gazette, October 31, 1946.

3 Tom Gorman and Jerome Holtzman, Three and Two! (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1979), 8.

4 Gorman and Holtzman, 9-10.

5 Gorman and Holtzman, 21.

6 Gorman and Holtzman, 35.

7 Gorman and Holtzman, 36.

8 Gorman and Holtzman, 40.

9 Calculations performed by Dennis Bingham, using data on umpire ejections on Retrosheet.org.

10 Gorman and Holtzman, 60.

11 Brad Wilson, “Gorman, Umpire of the Year starting his 25th season in NL,” The Sporting News, March 15, 1975: 39.

Full Name

Thomas David Gorman

Born

March 16, 1919 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

August 11, 1986 at Closter, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.