Tom O’Rourke

Born with a celebrated baseball surname1 but with only a modicum of playing ability, catcher Tom O’Rourke was largely a nonentity on the 19th-century major league ballclubs that he played for. But on occasion, he provided useful service. O’Rourke’s post-baseball life followed a similar pattern – but for an altogether different organization: Tammany Hall, the corrupt political powerhouse that controlled Democratic Party affairs in New York City for generations. Although little more than a Wigwam foot soldier, O’Rourke occasionally proved helpful to the organization, particularly when it came to Tammany election-rigging exercises, twice getting himself indicted in the process. He beat the rap both times. In recognition of his devotion to the cause, O’Rourke was the beneficiary of Tammany largesse, regularly installed in minor local government posts. He was in residence in one such sinecure at the time of his death in 1929. The life story of this fringe actor on the baseball and political scenes of yesteryear follows.

Born with a celebrated baseball surname1 but with only a modicum of playing ability, catcher Tom O’Rourke was largely a nonentity on the 19th-century major league ballclubs that he played for. But on occasion, he provided useful service. O’Rourke’s post-baseball life followed a similar pattern – but for an altogether different organization: Tammany Hall, the corrupt political powerhouse that controlled Democratic Party affairs in New York City for generations. Although little more than a Wigwam foot soldier, O’Rourke occasionally proved helpful to the organization, particularly when it came to Tammany election-rigging exercises, twice getting himself indicted in the process. He beat the rap both times. In recognition of his devotion to the cause, O’Rourke was the beneficiary of Tammany largesse, regularly installed in minor local government posts. He was in residence in one such sinecure at the time of his death in 1929. The life story of this fringe actor on the baseball and political scenes of yesteryear follows.

Thomas Joseph O’Rourke was a lifetime New Yorker, born on the Upper West Side of Manhattan on an uncertain date during the early 1860s, most likely in 1863.2 He was the oldest of three children begat by common laborer Bernard O’Rourke (1841-1896), an Irish Catholic immigrant, and his first wife, all traces of whom are now lost to time except for the fact that she died while her offspring were still young. Bernard’s remarriage to Irish immigrant Elizabeth McDonough (c. 1841-1897) in May 18693 subsequently provided young Tom with a stepmother and at least two half-siblings.4 Nothing else about his youth has been uncovered. By age 18, however, he was employed as a neighborhood store clerk.5

The pivotal event in Tom O’Rourke’s life occurred in 1884 when he became the catcher for the New York Senators, a semipro nine organized by Charles F. Murphy, then a young West Side saloonkeeper. Not much older than O’Rourke, Murphy (1858-1924) himself had been the club’s original backstop.6 By the mid-1880s, however, the shrewd and taciturn “Silent Charlie” had embarked upon the course that culminated in his elevation to Tammany Hall chief in 1902. During Murphy’s astute 22-year stewardship, the Wigwam exerted disproportionate influence over Democratic Party affairs at the national, state, and municipal level. Murphy protégés included future New York Governor and 1928 Democratic presidential candidate Al Smith; longtime New York Senator Robert F. Wagner, Sr., and New York City Jazz Age Mayor James J. Walker (as well as “Miracle Braves” owner James Gaffney). Our subject never ascended to anywhere near such dizzying political heights, but his association with Boss Murphy was vital to his future, providing Tom with both his start in baseball and his subsequent access to Gotham political goodies.

O’Rourke entered the ranks of professional baseball in 1885 when he signed with the Toronto Torontos of the newly formed minor Canadian League. In 41 games for a third-place (24-20, .545) ballclub, he batted a tepid .205, with only one of his 35 hits going for extra bases. The wiry 5-foot-9, 158-pound redhead threw and hit right-handed.

In terms of statistical performance, O’Rourke reached the peak of his career the following season as a member of the Portland (Maine) entry in the New England League. In 92 contests for the 1886 circuit champions (66-36, .647), he posted a pro career-high.274 batting average (92-for-335).7 His defensive work was also commendable, with a local newspaper reporting that O’Rourke “is quick and always active, an excellent back stop and a good thrower.”8 Overall, Tom played well, with a final-season .932 fielding percentage being another career best.9 Enamored of O’Rourke’s performance, appreciative Portland fans halted the progress of a late-season game to present him with “a beautiful bouquet” of flowers.10

O’Rourke’s solid season in Portland did not go unnoticed, and during the offseason he was signed by the National League’s Boston Beaneaters. Like other major league clubs at the time, Boston paired their pitching and receiving corps into semi-permanent batteries. As the 1887 campaign began, O’Rourke was assigned to hard-throwing but erratic right-hander Bill Stemmeyer, a difficult man to catch – particularly for a likely barehanded receiver like O’Rourke.11 The previous year, Stemmeyer had won 22 games and led NL pitchers in strikeouts per nine innings. But he also walked 144 batters and led the league in wild pitches thrown (63).

O’Rourke made his major league debut on May 11, 1887, handling Stemmeyer in a 9-4 home game loss to the Philadelphia Phillies. The contest yielded two takeaways regarding the catcher’s future in the big leagues. First, his hitless day at the plate inaugurated a recurring event. O’Rourke simply could not hit major league pitching. Second, he was charged with two errors and two passed balls,12 presaging the dismal defensive stats that characterize his playing record.

Yet, curiously, reporters who witnessed the game praised O’Rourke’s performance. “O’Rourke made his first appearance behind the bat and proved himself a prize,” the Boston Journal declared. “He made several difficult catches and allowed but one ball to slip through his fingers. … His throwing to bases was excellent.”13 Boston Globe sportswriter William I. Harris concurred, stating that the work of “Tom O’Rourke … as a catcher … was beyond praise. He had a great deal to do and did it well. He made a good first impression and was loudly applauded by the 3,500 people present.”14 Even the opposition press approved, with the Philadelphia Inquirer observing that “O’Rourke made his debut … and his fine work behind the bat was highly complimented” by those in attendance.15

O’Rourke broke into the base hit column with a single off Pittsburgh Alleghenies right-hander Jim McCormick on May 18. He also contributed a walk, a stolen base, and a run scored as well as flawless defensive work to the Beaneaters’ 9-2 victory.16 But additional hits proved hard to come by as the season wore on. And errorless games became a rarity for the rookie receiver. At season end, both his batting and fielding stats were dismal. Appearing in 22 games for a (61-60-6, .504) fifth-place club, O’Rourke posted an anemic .154 batting average (12-for-78). His catching numbers were even worse: 31 errors, 16 passed balls, and a dismal .777 fielding percentage in 21 games behind the plate – well below the defensive marks posted by his fellow Boston backstops:

- Pop Tate (26 E, 24 PB, .924 FA in 53 games)

- Con Daily (21 E, 29 PB, .889 FA in 36 games)

- King Kelly (15 E, 21 PB, .885 FA in 24 games)17

Notwithstanding his poor numbers, O’Rourke was retained on the Boston roster and teamed with newcomer Bill Sowders as the 1888 season opened. The oddly named “German battery” got off to a good start with a 7-1 victory over Philadelphia on April 24. As before, the newspaper game accounts and the box score told different stories when it came to “the Irish end” of the twosome. In the view of the Boston Globe, “Tom O’Rourke … did most excellent work” behind the plate,18 while the Boston Herald reported that “O’Rourke held [pitcher Sowders] in superb style, and threw to bases very finely.”19 Yet the box score contained the customary O’Rourke demerits: two errors and a passed ball.20

As the season progressed, good games were infrequent events for Tom O’Rourke. Again, he did not hit, posting a .176 (13-for-74) batting average in 20 game appearances, and his defense, while improved, was still no more than adequate – at least on paper (17 E, 14 PB, with an .881 FA). On August 9, Boston gave O’Rourke his 10 days’ notice of release.21 Tom spent the next several weeks back home in Manhattan before signing with a nearby minor league club, the Jersey City Skeeters of the Central League.22 That September, he saw sparing action as his new club’s second-string receiver.

Whatever his tribulations on the diamond, the year 1888 was a good one in Tom O’Rourke’s personal life. Sometime during that year, he married Catherine Byrne, like himself a Manhattan native of Irish Catholic descent. And within the next 15 years, the couple were blessed with eight children.23

When the Central League dissolved over the winter, Jersey City joined the newly-formed Atlantic Association for the 1889 campaign. And O’Rourke began the season in Skeeters livery.24 But in early May he was released, only to be signed thereafter by an Atlantic Association rival, the New Haven (Connecticut) club.25 In addition to catching, the athletic O’Rourke also filled in at second base, shortstop, and the outfield for his new team. But he still could not hit, and he was jettisoned by New Haven in early August. Club directors cited O’Rourke’s “high salary” as the reason for his release,26 but rumors swirled that Tom had been let go for sabotaging the debut of young New Haven pitcher Charles Sanborn.

O’Rourke accepted the trimming club expenses rationale offered for his release gracefully, stating, “I am here to get a living at ball playing. If the directors think they can get another man who can do as good work at a lower figure, it is the policy to get him.”27 But he indignantly denied that he had deliberately underperformed during Sanborn’s maiden outing. “The charge was utterly false,” O’Rourke declared. “I played the best game possible Tuesday, and had no object in attempting to freeze Sanborn out.” He also empathized with the rookie hurler’s situation, observing that he, too, “was young once and had to make a start in this business.”28

Teammates and the local press rallied to O’Rourke’s defense, with alternate New Haven catcher Tommy Cahill repudiating reports that he had accused our subject of malfeasance during the Sanborn outing. “O’Rourke, in my opinion, caught a praiseworthy game,” declared Cahill in a letter published in the New Haven Evening Register.29 In expressing its regret regarding O’Rourke’s departure, the newspaper added a testimonial, as well, stating that he had “always conducted himself in a gentlemanly manner and made a host of friends during his stay here.”30

After a few weeks of unsought respite back home in Manhattan, O’Rourke returned to the game, signed by yet another Atlantic Association club, this one based in Hartford.31 As usual, his defensive work in his Hartford debut was praised in the press:

- Hartford Courant: “Tom O’Rourke … caught both [pitchers] Smith and Winkelman in a masterly fashion”32;

- New Haven Evening Register: “Tom O’Rourke came up from New York and caught a fine game.”33

However, the box score revealed that he was charged with his standard two passed balls.34 Furthermore, O’Rourke’s batting performance was constant: a powerless .224 BA (36-for-161) in 45 games for New Haven and Hartford, combined.35

Detailed discussion of the turmoil on the major league baseball scene created in 1890 by the advent of the Players League is beyond the scope of this profile. Suffice it to say that Tom O’Rourke was one of its inadvertent beneficiaries. Of all the National League clubs affected by player defections to the newly arrived circuit, none was hit harder than the defending world champion New York Giants. With the exception of outfielder Mike Tiernan and fading staff stalwart Mickey Welch, the Giants lost their entire lineup to the Players League. And with future Hall of Famer Buck Ewing now installed at the helm of the PL’s New York club, the position perhaps most in need of shoring up on the NL New York Giants was that of catcher.

Among those auditioned to fill the Ewing vacancy was Tom O’Rourke. But after going hitless, committing three errors, and being charged with five passed balls during his two-game Giants tryout, O’Rourke was released.36 Weeks later, he signed with the Syracuse Stars,37 another beneficiary of Players League-created chaos. A member of the minor league International Association during the 1889 season, the Stars were elevated to major league status in 1890 upon becoming a replacement for one of the four franchises lost by the American Association.38

The Stars had a few capable players, such as second baseman Cupid Childs, first baseman Mox McQuery, and third baseman Tim O’Rourke, another redheaded Irishman with whom our subject is occasionally confused. But for the most part, the Syracuse roster was comprised of marginal talents, and Tom O’Rourke fit right in. In 41 contests, he batted a mild .216 (33-for-153), while his .907 FA featured 24 errors. He also registered 35 passed balls. On August 1, 1890, five O’Rourke passed balls were largely the difference in a 6-5 Syracuse loss to the Louisville Colonels.39 After the game, Syracuse manager Wallace Fessenden fined his catcher $25 and suspended him without pay.40 The sanction was promptly denounced as unwarranted by the New York Times. “Just why O’Rourke should be treated in this way is not plain. O’Rourke is one of the most reliable and conscientious players to be found,” the Times proclaimed, before adding, curiously, that “if [O’Rourke] did poorly it was because he was not in condition.”41

O’Rourke was equally perturbed by his punishment and refused to pay the fine. Such insubordination, however, was not to be tolerated by Syracuse club boss George K. Frazier, who had just fired manager Fessenden and taken over running the Stars himself. The ensuing release of the recalcitrant backstop brought the major league playing career of Tom O’Rourke to a close.42

As suggested by the regular newspaper praise of O’Rourke’s work, he must have been a better player in person than he appears to have been statistically. For O’Rourke’s numbers are terrible. In 85 major league games, he posted a woeful .186 career batting average (58-for-312), utterly lacking in power. Indeed, he never notched a base hit worth more than two bases – and he hit only 11 of those. O’Rourke’s career RBI (26) and runs scored (32) totals are also meager. Many 19th-century catchers, of course, compensated for a weak bat by playing sterling defense. But here, too, O’Rourke’s numbers are lackluster: 370 putouts/118 assists/75 errors (plus 70 passed balls) in 83 games behind the plate yields a .867 career fielding percentage.

His release by Syracuse may have ended O’Rourke’s major league days, but he did not abandon the game just yet. He finished the year playing for a fast Manhattan semipro club called the West Ends.43 In April 1891, he suited up for the New York Giants once again, catching fireballer Amos Rusie in a preseason exhibition match against the Princeton University varsity. By game’s end, O’Rourke had demonstrated his usual form, going hitless while committing two errors and being charged with three passed balls.44 Courtesy of “two disastrous throws”45 by the catcher in the eighth inning, Princeton took a 1-0 lead into the final frame. But a last-gasp four-run rally spared the Giants the embarrassment of losing to collegians.

Shortly thereafter, O’Rourke rode a train west for his final professional engagement – a stint with the Denver Mountaineers of the minor league Western Association. The Chicago Inter Ocean congratulated Denver for getting “one of the best catchers in the country,”46 while the Boston Globe speculated that the “rarified air up in that altitude may be just the thing for Tom.”47 He lasted five games. Thereafter, O’Rourke and his .235 (4-for-17) batting average were excused from further play. His quick severance by Denver completed Tom O’Rourke’s time on professional diamonds.

O’Rourke’s pro ballplaying days may have been behind him, but he still had a wife and growing family to support. Tammany Hall promptly came to the rescue. The Wigwam set O’Rourke up in a West Side saloon that quickly became a meeting place for Tammany insiders. Tammany also arranged for Tom to receive a $1,000 annual stipend for serving as a messenger. All of this was publicly revealed a few years later when O’Rourke got into a brief legal scrape for starting construction of a building without first having obtained the requisite permit.48

In September 1897, O’Rourke was tabbed to serve as a Tammany delegate to the New York City Democratic Party convention.49 And shortly into the new century, he was appointed a New York (Manhattan) County deputy sheriff.50 In 1906, Deputy Sheriff O’Rourke was a Charles F. Murphy-loyal delegate to the New York State Democratic Party convention in Albany.51 Back home in his local district, Tom organized the Tamarrora Club with headquarters over his saloon, a fraternal front designed to further the ambitions of 17th Assembly District leader Roswell D. Williams, O’Rourke’s immediate Tammany superior. In 1909, that association landed Tom in the dock, criminally charged along with Williams and others by the Republican-run Attorney General’s Office with election fraud during a recent Democratic primary.52 As alleged in the indictments, O’Rourke was among the Williams goons who stormed a polling place deemed friendly to an upstart rival candidate, confiscated already cast ballots, and replaced them with ones supplied by the Williams forces. Additional indictments returned in February 1910 piled more election-rigging charges on Williams, O’Rourke, and their codefendants.53

Brought to trial in May, the accused categorically denied the charges. Taking the stand in his own defense, O’Rourke admitted being at the polling location where a multitude of prosecution witnesses described the assault of election workers, theft of ballot boxes, and their replacement by new ballot boxes furnished by the accused – but O’Rourke blithely denied seeing anything like that.54 When the 4,003 ballots surviving the polling station fracas were counted, every one – remarkably – had been cast for lead defendant Williams. Unhappily for the prosecution (which had been unable to bring along upstate Republican jurors), hometown Tammany-territory jurymen were unimpressed. The accused were acquitted, an outcome that the New York American later deemed a “miracle,”55 but one which more jaded observers found predictable.56

In May 1911, continued prosecution of district leader Williams and his minions (including O’Rourke) was put to an end when a criminal court judge dismissed the outstanding indictments pending against them.57 But not everything had gone swimmingly for Tom O’Rourke while he was under indictment. A change at the top in the sheriff’s office had cost him his deputy’s position,58 and he appears to have been in financial distress during this period.59 But Tammany again came to the rescue, finding O’Rourke a clerk’s position in the city comptroller’s office. Later, he was installed as secretary to the board of water supply, the post that O’Rourke held at the time of his death.

As he entered his sixties, Tom began to exhibit signs of heart disease. On July 19, 1929, he died from complications of that malady inside his West Side Manhattan home. Locally published obituaries placed his age at 66.60 Following a Requiem Mass said at the Church of the Holy Name in Manhattan, the deceased was interred at Calvary Cemetery in Woodside, Queens. Predeceased by his wife, Thomas Joseph O’Rourke was survived by his adult children William, Irene, Thomas, Frank, and Catherine.

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Darren Gibson and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Terry Bohn.

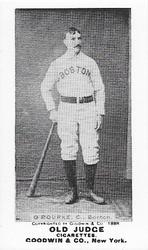

Photo credit: Tom O’Rourke, Trading Card Database.

Sources

Sources for the biographical information imparted above include the Tom O’Rourke file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; the O’Rourke mini-bio in Major League Player Profiles, 1871-1900, Vol. 1, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011); US and New York State census data accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Unless otherwise specified, statistics have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 By the conclusion of the 2024 season, there had been 10 major leaguers named O’Rourke, the majority of whom played in the 19th century. The most famous was Hall of Famer Jim O’Rourke, but neither Orator Jim nor any of the other ballplaying O’Rourkes were related to our subject.

2 Modern baseball reference authority list Tom O’Rourke’s birth as occurring in October 1865, a date apparently predicated on the 1900 US Census. But other US and New York State censuses indicate birth years from 1862 to 1867 for him. Resolution of the issue awaits more definitive data. In the meantime, the best evidence currently available (which includes his TSN player contract card and his 1929 newspaper obituaries) suggests that O’Rourke was actually born sometime in 1863.

3 State of New York marriage records establish that Bernard O’Rourke and Elizabeth McDonough were married in Manhattan on May 24, 1869.

4 Tom’s siblings were William (born c. 1864) and Mary (1867). His half-brothers were Bernard Jr. (1872) and Cyrenus Lawrence (1881).

5 Per the 1880 US Census.

6 See Thomas F. Comiskey, “Baseball, Bars, No Blarney: Charles F. Murphy’s Path from Gas House District to Tammany Hall Boss,” The Village Sun, May 7, 2024, available online.

7 Per New England League batting stats published in the 1887 Reach Official American Association Guide, 69. Baseball-Reference provides no data for O’Rourke’s 1886 season.

8 “Athletic Sports: Base Ball,” Portland (Maine) Daily Press, April 28, 1886: 1.

9 1887 Reach Guide, 71.

10 As reported in “Base Ball: The New England League,” Portland Daily Press, September 8, 1886: 1.

11 Although rudimentary catcher’s gloves had been available since the mid-1870s, O’Rourke’s 1887 playing cards depict him catching barehanded. The only discovered image of O’Rourke using protective gear is an 1890 playing card which shows him wearing skin-tight gloves on both hands and a chest protector.

12 Per box scores published the following day in the Philadelphia Inquirer, Boston Globe, and elsewhere. O’Rourke was charged with only one error, however, in the Boston Journal box score.

13 “Base Ball,” Boston Journal, May 12, 1887: 3.

14 William I. Harris, “The Small End,” Boston Globe, May 12, 1887: 5.

15 “The Phillies Win,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 12, 1887: 3.

16 Per the box score and game account in “Six Straight,” Boston Globe, May 19, 1887: 2.

17 The Boston catcher fielding averages incorporate stats from other positions, as well.

18 “Four Straight,” Boston Globe, April 25, 1888: 3.

19 “This Time 7 to 1,” Boston Herald, April 25, 1888: 5.

20 Per the Boston Globe box score.

21 As reported in “New Players Signed,” Cleveland Leader, August 10, 1888: 3.

22 O’Rourke’s signing with Jersey City was reported in “Bat and Rack,” Boston Herald, September 9, 1888: 2, and “Jerseymen Overmatched,” New York Tribune, September 7, 1888: 3. Baseball-Reference also lists our O’Rourke as playing for the Hazelton (Pennsylvania) Pugilists, another Central League team during the 1888 season, but that player was likely Joe O’Rourke.

23 The 1910 US Census lists Anne O’Rourke as the mother of eight children, five living. William (born 1889), Irene (1892), Thomas (1894), Francis (1896), and Catherine (1898) outlived their parents while, sadly, Jack (1903) and two unidentified O’Rourke children did not survive infancy.

24 As confirmed in “The Atlantic League,” New Haven (Connecticut) Evening Register, April 6, 1889: 4.

25 As reported in “Base Ball Matters,” Meriden (Connecticut) Daily Journal, May 9, 1889: 6, and “World of Sports,” Waterbury (Connecticut) Evening Democrat, May 9, 1889: 4.

26 Although O’Rourke’s stipend was not publicly disclosed, he was “the highest paid man on the team.” See “O’Rourke Is Released,” New Haven Evening Register, August 8, 1889: 1. See also, “O’Rourke Released,” New Haven (Connecticut) Daily Morning Journal and Courier, August 9, 1889: 3. A season later, O’Rourke wanted a $300 per month salary plus other benefits to play for the Hartford club. See “World of Sport,” Waterbury Evening Democrat, May 21, 1890: 5.

27 “O’Rourke Is Released,” above.

28 Same as above.

29 “Catcher Cahill Was Only Joking,” New Haven Evening Register, August 9, 1889: 1. In Cahill’s estimation, most of pitcher Sanborn’s problems stemmed from his inability to hold runners close to the base.

30 “Atlantic League Clubs,” New Haven Evening Register, August 9, 1889: 1.

31 As reported in “Base Ball Gossip,” New Haven Evening Register, August 27, 1899: 1.

32 “Base-Ball: Atlantic Association,” Hartford Courant, August 28, 1889: 5.

33 “MacDonald to Resign,” New Haven Evening Register, August 28, 1889: 1.

34 See again, “Base-Ball: Atlantic Association,” above.

35 Per Atlantic Association stats published in the 1890 Reach Official American Association Guide, 78.

36 O’Rourke’s release by the Giants was reported in “Miscellaneous Sporting Notes,” Saginaw (Michigan) Evening News, May 8, 1890: 7, and “Base Ball Gossip,” Holyoke (Massachusetts) Daily Transcript, May 7, 1890: 1.

37 The Syracuse signing of O’Rourke was memorialized in “Base Ball Notes,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 26, 1890: 5; “Basehits,” Buffalo Express, May 25, 1890: 14; and elsewhere.

38 The defending American Association champion Brooklyn Bridegrooms and the AA Cincinnati Reds jumped to the National League, while the AA Baltimore Orioles and Kansas City Cowboys elected to affiliate with minor leagues for the 1890 campaign.

39 According to the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 2, 1890: 7: Syracuse “would not have lost the game if had it not been for O’Rourke’s poor catching.” See also, the Buffalo Express, August 2, 1890: 6: “O’Rourke’s five passed balls were very costly to the Stars.”

40 As reported in “Miscellaneous Sporting Notes,” Saginaw Evening News, August 9, 1890: 3; “Two-Baggers,” Boston Herald, August 5, 1890: 4; and elsewhere.

41 “Notes,” New York Times, August 4, 1890: 2. Despite the insinuation arising from allusion to not being in condition, there is no evidence that Tom O’Rourke was a drinker.

42 O’Rourke’s release by Syracuse was reported in “Base Ball Notes,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 6, 1890: 7. See also, the Tom O’Rourke entry in Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Vol. 1, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 268.

43 See “Base Ball,” Plainfield (New Jersey) Evening News, September 25, 1890: 1.

44 Per the box score in “Princeton Collegians Scare the Giants,” New York Herald, April 5, 1891: 22.

45 “Princeton Collegians,” above.

46 “All Sorts of Sport,” Chicago Inter Ocean, May 1, 1892: 2.

47 “Must Have the Best,” Boston Globe, April 28, 1892: 5.

48 See “Began to Build Without a Permit,” New York Herald, June 19, 1895: 4. Presumably, the needed authorization was soon supplied by the Tammany-controlled city building department.

49 Per “Tammany Hall Delegates,” New York Times, September 22, 1897: 2.

50 As reflected in newspaper advertisements of sheriff sales of confiscated property.

51 Per “Two Rival Delegations Chosen in Seventeenth,” New York American, September 23, 1906: 4, and “Murphy Factions Hold 4 Rival Conventions,” New York Times, September 23, 1906: 5.

52 As reported in “Charged with Ballot Stealing,” New York Daily People, October 16, 1909: 1; “Tammany Men Surrender,” New York Evening Post, October 15, 1909: 3; and elsewhere.

53 See “Indicted for Election Frauds,” New York Daily People, February 25, 1910: 2; “Williams Indicted Again,” New York Sun, February 24, 1910: 6; “Williams Indicted Again,” New York Tribune, February 24, 1910: 3.

54 “Williams Denies It All,” New York Tribune, May 19, 1910: 2.

55 “Financial Expert Denies His Agency Gave Fuller Firm a ‘Clean Bill,’” New York American, May 18, 1923: 11.

56 The verdict details appear in “Williams Is Freed Despite Jury Charge,” New York American, May 21, 1910: 4; “Wiliams and Six Free,” New York Tribune, May 21, 1910: 16.

57 See “Primary Indictments Fail,” New York Sun, May 5, 1911: 5.

58 See “Shea Takes Foley’s Place,” New York Times, January 2, 1910: 2.

59 At this far a remove in time it cannot be determined for certain, but our subject is likely the same Thomas J. O’Rourke adjudicated bankrupt in April 1910. See “Bankruptcy Notices,” New York Times, April 29, 1910: 14.

60 See “Thomas J. O’Rourke,” New York Times, July 20, 1929: 55; “Thomas J. O’Rourke, Ex-Catcher, Dies,” New York Evening Post, July 19, 1929: 12.

Full Name

Thomas Joseph O'Rourke

Born

, 1863 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

July 19, 1929 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.