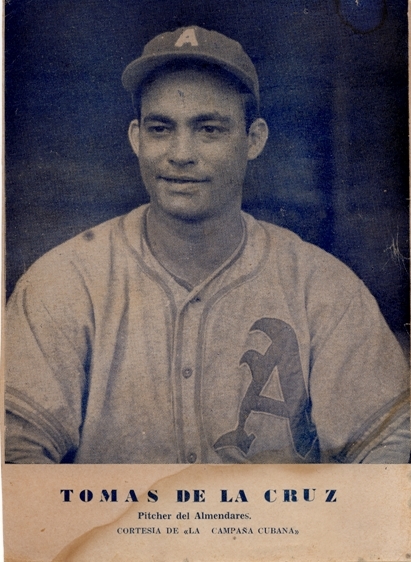

Tommy de la Cruz

“And in no field of American endeavor is invention more rampant than in baseball, whose whole history is a lie from beginning to end. … The game’s epic feats and revered figures … all of it is bunk, tossed up with a wink and a nudge.” — John Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden

The half-decade-plus spanning American involvement in the Second World War provides an odd assortment of remarkable baseball tales and largely forgettable baseball figures. Foremost in the inventory of historical flotsam stands a ragtag contingent of marginal ballplayers often elevated to big-league prominence far beyond their talents, as well as an assortment of budding legends all too quickly buried in the dustbin of history once the mid-1940s brought a return to peacetime normalcy. There were raw youngsters who arrived well before their time (to wit, a shaky 15-year-old Joe Nuxhall in Cincinnati), physical cripples who appeared more as oddities than anything else (especially a much-maligned one armed flychaser aliased Pete Gray in St. Louis), and overachieving wonders who became stars against largely subpar competition (exemplified by near-30-game winner Hal Newhouser in Detroit).1 And there were also oddballs who crossed into history as unlikely pioneers once given their ill-fated moment in the sun. None in this assortment of unlikely star-crossed pioneers provides a more intriguing if largely underappreciated story than statuesque Cuban-born hurler Tomás de la Cruz Rivero, a hard-throwing Afro-Cuban of more than average talent whose rightful place in the game’s annals has now been largely obliterated by the twists and vagaries of midcentury historical accidents.

The half-decade-plus spanning American involvement in the Second World War provides an odd assortment of remarkable baseball tales and largely forgettable baseball figures. Foremost in the inventory of historical flotsam stands a ragtag contingent of marginal ballplayers often elevated to big-league prominence far beyond their talents, as well as an assortment of budding legends all too quickly buried in the dustbin of history once the mid-1940s brought a return to peacetime normalcy. There were raw youngsters who arrived well before their time (to wit, a shaky 15-year-old Joe Nuxhall in Cincinnati), physical cripples who appeared more as oddities than anything else (especially a much-maligned one armed flychaser aliased Pete Gray in St. Louis), and overachieving wonders who became stars against largely subpar competition (exemplified by near-30-game winner Hal Newhouser in Detroit).1 And there were also oddballs who crossed into history as unlikely pioneers once given their ill-fated moment in the sun. None in this assortment of unlikely star-crossed pioneers provides a more intriguing if largely underappreciated story than statuesque Cuban-born hurler Tomás de la Cruz Rivero, a hard-throwing Afro-Cuban of more than average talent whose rightful place in the game’s annals has now been largely obliterated by the twists and vagaries of midcentury historical accidents.

On the surface Tommy de la Cruz was little more than an “emergency” foreign import who enjoyed one moderately successful National League campaign in Cincinnati and then faded nearly overnight from the limelight of the sport’s biggest stage. In the hefty record books documenting the sport’s massive historical legacy the Havana-born right-hander owns a single not-altogether insignificant landmark achievement as the very first Latin American mound ace to author a complete-game one-hitter on a big-league diamond. His 9-9 won-lost mark over a single summer (1944) also makes him one of the more accomplished among several dozen pioneering pre-1950 journeymen Cuban recruits brought to the big time mostly by Washington Senators superscout Papa Joe Cambria. Only a single Cuban (Adolfo Luque, who logged 27 wins for Cincinnati in 1923 and 194 in a 20-year sojourn) ever won in double figures before Washington’s 40-year-old Conrado Marrero posted a creditable 11-9 American League mark in 1951, but de la Cruz had narrowly missed that magical level by only an eyelash seven seasons earlier, and his 18 decisions in a single campaign were the most for a Cuban native in the four decades separating the debuts of Luque and Marrero.2

The bulk of the mostly cup-of-coffee pre-1950 Cuban imports signed on with the Washington Senators and few had much impact before Marrero in 1951 and again in 1952 (when the colorful fireplug-shaped “El Señor” also won 11 for manager Bucky Harris’s second-division Senators). A handful of others (28 in total before de la Cruz appeared in Cincinnati in April of 1944) labored over the decades with several other big-league clubs (nine with Washington and four each with the Giants and the Reds) but outside of Luque and catcher Mike González (who both hung around for two full decades) only outfielder Armando Marsans, catcher Mike Guerra, and infielder Roberto Estalella lasted as long as eight seasons. These pioneering second-tier Cubans were mostly but not exclusively light-skinned islanders (at least not overly dark-skinned ones) who could slip past (albeit not without considerable press controversy and fan grumbling) the odious racial barriers defining segregated “organized” professional baseball. A few (including Luque, Marsans, González and later even Orestes Minoso) played not only in segregated white men’s leagues (both majors and minors) but also in various largely colorblind blackball circuits.3

If de la Cruz earned some small measure of renown and a certain indelible niche with his pioneering one-hit masterpiece tossed late in the 1944 season, his true claim to exceptionalism undoubtedly came with his role as a racial pioneer. Official MLB historian John Thorn has eloquently reminded us that so much of baseball’s most cherished “history” (events recorded in scholarly volumes and entrenched in popular lore) is at least to some degree a baldfaced lie, and that dictum ruthlessly applies to many of the game’s most treasured landmarks. Not exempt of course is the celebrated and even iconic racial integration role shared by Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey. Nothing should of course detract from Robinson’s landmark 1947 achievement (as MLB’s first modern-era African American), or taint his gutsy exceptionalism and unarguable bravery during those first several seasons in Brooklyn. But the sport’s integration process was never a simplistic event reducible to a single act by a single individual (or even by a pair of individuals). Like Alexander Cartwright’s crafting of the game’s first rules in Hoboken, Candy Cummings’ ingenious discovery of the curveball on the sandlots of Brooklyn, or the Babe’s “called shot” in Wrigley Field, that landmark integration process never transpired with one singular event quite the way it has now been told, retold, and inevitably embellished for more than a half-century of mythmaking.

Before Jackie Robinson came on the scene there were Roberto Estalella, Alex Carrasquel, Hiram Bithorn, and Tommie de la Cruz – Caribbean-born foreign imports with more than a small trace of African bloodlines to strain the boundaries of segregated North American professional baseball. The first half of the 20th century featured a small parade of swarthy-skinned athletes of suspected African heritage who sneaked furtively over, under, and around the racial barriers erected by the big-league establishment under the guise of a “gentlemen’s agreement.” Some were Afro-Cubans (Estalella and de la Cruz and perhaps a half-dozen others before them) and others were Puerto Ricans (Bithorn), Mexicans (Mel Almada), and Venezuelans (Carrasquel). They stirred up various degrees of disturbance and various degrees of controversy. The rarely told story goes back as far as the early twentieth century and the arrival of the first modern-era big-league Cubans, infielder Rafael Almeida and outfielder Armando Marsans, who initially showed up in the Cincinnati lineup on the same day in midseason 1911. When Reds manager Clark Griffith first inserted the pair of Cuban imports onto his roster at Chicago’s West Side Grounds on July 4, the outcry was sufficient to send club management scrambling for reports from Havana to verify that Griffith’s Cubans were in fact “two of the purest bars of Castilian soap ever floated to these shores.” The furor surrounding Marsans and Almeida was immediate and incendiary but nonetheless was quickly enough swept aside (largely in the light of Cincinnati owner Garry Herrmann’s seemingly sincere protestations) and thus an important if troubling trend of racial boundary-bending was first set in motion.4

Neither Marsans (who claimed Basque ancestry) nor Almeida (who was “white” by reigning Cuban standards) may have actually possessed much African blood and their cases may have been something of a media red herring. But racial-makeup questions soon greeted the big-league appearances of two additional Cubans of the same era – outfielder Jacinto “Jack” Calvo and pitcher José Acosta, who both labored briefly in the nation’s capital in the early 1920s. Even more troubling to the mainstream media were the 1930s-era Washington appearances of pioneering Venezuelan pitcher Alejandro “Alex” or “Paton” Carrasquel (the first big leaguer from that country) and Cuban infielder Roberto “Bobby” Estalella. Carrasquel (another Cambria signee whose career was obviously enhanced by wartime player shortages) passed only tolerably well for a white player between 1939 and 1945, winning 50 games overall for the second-division Senators. The Venezuelan was repeatedly heckled around the circuit for his dark complexion by fans and opponents alike (as Dolph Luque also had been in earlier decades), and when he tried to avoid attention by anglicizing his name to Alex Alexandria (a ploy formally announced to the Washington press), the beat writers around the league simply began calling him Carrasquel the Venezuelan (in many circles a polite substitution for using the N word). More controversial still was the popular Estalella, a fan favorite around the circuit for his slugging and reckless third-base play and believed to be the first Cuban recruit signed up by Joe Cambria. Popularly dubbed “Tarzan” for his statuesque build, the colorful Cuban import (colorful in facial tones as much as in playing style) was, according to one recent author, “the first man of recognizable African ancestry to play Major League Baseball in the US.”5

If Estalella somehow managed to remain under the radar of harsh racial restriction, the same was also largely true of Hiram Bithorn of the Chicago Cubs during the earliest years of World War II. Puerto Rico’s first big leaguer pitched well enough with the 1942-43 Cubbies to claim 27 victories (he lost 26) over the two campaigns before wartime service largely sabotaged his budding career.6 If Bithorn and his regular catcher (Cuban teammate Salvador “Chico” Hernández) – as one of the early all-Latino battery in MLB annals – did not raise as much furor in Chicago as Estalella and Carrasquel had stirred in more Southern-lying Washington, they hardly escaped the attention of racial hardliners. No less an authority than the renowned writer Fred Lieb would years after the fact figuratively “blow the whistle” regarding Bithorn. For Lieb there was solid enough evidence of the Puerto Rican pitcher’s African bloodlines for him to report in his 1977 memoir that “for a while I thought Bithorn … might be entitled to be called the first black player to appear in a big league uniform.” Lieb’s suspicions had been spurred by a 1947 encounter with an all-black dance troupe in St. Louis where one of the ebony-skinned performers introduced herself as Hi Bithorn’s first cousin.7 Nonetheless, Lieb was a good soldier (so much so that he remained silent on the issue at the time) and he would end his brief 1977 exposé with a largely hollow effort at an appropriate caveat, reporting that at the time back in 1942 he had been “assured by a Puerto Rican baseball authority that Bithorn was not black, despite my curious experience.”

The ploy of dark-skinned Cubans or Latinos being passed off as foreigners and not “true blacks” (i.e., those of the African-American variety) has a lengthy legacy in the folklore as well as the legitimate history of the sport. Its corollary is African American players themselves attempting to pass as exotic Cuban islanders and thus pique fan interest and increase gate revenues by spouting Spanish-sounding gibberish while barnstorming across the North American Midwest.8 It starts perhaps with 1901 Baltimore Orioles skipper John McGraw and his “Indian” recruit Chief Tokohoma (actually a black American named Charlie Grant) on the spring-training diamond in Hot Springs, Arkansas.9 There are also a multitude of examples in baseball’s fictional literature of a kind perhaps best illustrated in Paul Hemphill’s entertaining 1979 novel Long Gone.10 And there was of course the standard apocryphal quote repeated ad nauseam about Cuban stars discovered on the early island barnstorming circuits (and attributed to McGraw and a handful of different managers and ballplayers who toured early twentieth-century Cuba): “Cover up a José Méndez or Cristóbal Torriente or Pablo Mesa with a gallon of liquid whitewash and the ebony-toned Cuban could easily demand the hefty bankroll salary of a Christy Mathewson or a Ty Cobb or a Tris Speaker.”

Into this mix stepped Cuban hurler Tomás de la Cruz during perhaps the most disruptive of big-league baseball’s four-plus wartime seasons. That 1944 represented the pinnacle of the wartime player depletion is well enough illustrated by the heretofore sad-sack St. Louis Browns (second-division residents in 13 of 14 previous seasons) who walked off with an unlikely American League pennant despite being saddled with a roster including an all-4-F infield and nine long-toothed veterans over the age of 34. Like Bithorn in Chicago, Estalella in Washington, or Almeida and Marsans years earlier in Cincinnati, de la Cruz did not enter the scene without his share of grandstand and pressroom controversy, but Reds management once more simply repeated the mantra that the new recruit was merely Hispanic and not actually black. His time on the main stage would not last very long but it was nonetheless sufficiently productive by most standards. He completed nine of 20 starts (fourth most starts on the club), logged 191-plus innings (fourth most), made an additional 14 relief appearances (tying him with Bucky Walters for the second most total appearances behind Clyde Shoun), and finished in the league’s top 10 in four less noticeable pitching categories And then in a cloud of deep mystery it was all suddenly over before the dawning of a second big-league campaign.

When Branch Rickey launched his now famous stateside integration plan during the same war-torn years, he reportedly also looked at least briefly in the direction of Cuba. Rickey apparently had yet another Cuban hurler in mind, one of the island’s biggest and most versatile stars. Rickey supposedly sent Walter O’Malley to Cuba to scout and even to interview Silvio García, a jet-black multitalented athlete who served equally well as a flashy shortstop (he had his supporters for the title of the island’s best ever) and a crafty right-handed pitcher (mostly in the 1937 season where he posted a sparkling 10-2 mark for Marianao). As a batter Garcia would eventually walk off with two league hitting titles and sported a wide reputation as one of the island’s best. But the recruitment plan was dropped almost as quickly as it was launched and García’s checkered reputation as a drinker and carouser often is offered as an explanation for Rickey’s rapid change of heart.

There are in fact numerous circulating speculations about why Rickey dropped his García recruitment plan, if indeed he had ever seriously considered it in the first place.11 There is the probably apocryphal interview with García in which Rickey asked “What would you do if a white man slapped your face?” and the volatile Cuban supposedly shot back, “I kill him!” The all-too-perfect and symbolic exchange is usually attributed to a report from Havana historian Eddie Casal, but without much solid documentation. There is the further report that Silvio had already been conscripted into the Cuban military. But logic also serves us even better here. Rickey from all other available accounts clearly had his sights on an African American and would not be content with merely slipping another Cuban through the back door. That had just been done with de la Cruz in Cincinnati two years earlier and rather obviously Rickey had much more dramatic fish to fry.

Tomás de la Cruz for his own part traveled a tortured and often rather obscure path toward a largely unacknowledged role in baseball’s eventual North American integration. And along that route of many twists and turns he would play rather key roles in several additional landmark baseball moments both at home in Cuba and abroad (especially in Mexico). His quixotic life both on the baseball diamond and off – from what little details we have access to – would offer a most dramatic tale even without any central or peripheral role as racial pioneer.

Little is known about the ballplayer’s origins, about his formative years in early twentieth century Cuba, or even about his premature demise. He remains largely a mystery away from the baseball diamond and that lack of concrete details about family origins only serves to muddy the waters concerning his actual racial makeup. De la Cruz was born in the Marianao district of Havana on September 18, 1914, but all further details appear to be hopelessly lost. Although reputable historian Robert González Echevarría provides a handful of useful if sketchy details he does nonetheless perhaps get the precise birth year incorrect. Indeed there is controversy in published volumes over the precise birth year, with both 1911 and 1914 appearing in reputable sources.12 De la Cruz attended the prestigious Marist School in his native city, where his baseball career apparently began when he was deemed light-skinned enough by Cuban standards to play for the magazine-sponsored Carteles youth team in a low-level city amateur circuit. There he was successful enough to hook on with the Central Hershey (Hershey Sugar Mill) ballclub of the top amateur circuit, the Cuban National Amateur Baseball League. Still only 17 (accepting González Echevarría’s birth year), de la Cruz immediately emerged as one of the circuit’s top arms, leading Hershey to a 1932 championship by logging eight of the club’s 18 victories while posting one of its mere two losses. A single year later he had switched allegiance to the Havana Electric Company squad of the city’s semipro circuit and again enjoyed considerable mound success.

De la Cruz earned his first professional shot with the local Marianao club managed by Joseíto Rodríguez during the subsequent 1934-35 winter-league season. It would be the first league campaign staged in a plush new La Tropical Stadium recently constructed for the 1930 Central American games and now pressed into service as replacement for a dilapidated Almendares Park. That historic 1934-35 campaign came on the heels of considerable political unrest surrounding the first twentieth-century Cuban revolution and the downfall of highly unpopular dictator-President Gerardo Machado. The civil strife had shortened the 1932-33 league campaign and forced a total shutdown of Cuban League play the following winter. Thus the season of de la Cruz’s professional debut was set against a backdrop of still-fomenting political turmoil as well as a shift to new upscale playing grounds. The location of the new venue in the city’s Marianao district likely played a role in lifting an inspired Marianao team into a runner-up slot in the thin three-team circuit. De la Cruz’s own surprising debut performance included the league lead in complete games (six) and the top mark in innings pitched (81). The surprising rookie’s 5-4 pitching record (his team was 12-16 for the season) – plus a second solid if less heady campaign in 1935-36 (4-9 for a last-place finisher but the league’s top mark in starts) – was enough to catch the attention of famed Washington bird dog and Havana resident Joe Cambria, who inked the youngster to a North American minor-league contract and shipped him off for summer duty in with the Albany Senators of the Double-A International League.

De la Cruz’s debut in Albany was also impressive enough despite a losing record with the league’s rather inept cellar-dwellers. The young Cuban finished 6-10, appeared in a club-best 50 contests, and posted the team’s fourth most innings pitched (187). The next couple of years were marked by a number of trades, the first one to the New York Giants organization on the eve of the 1937 season. That move found him pitching once more in the International League with yet another last-place outfit, Jersey City. On a ramshackle club that lost 100 games, the Cuban’s workload dropped considerably; he enjoyed only four starts, lost five of six decisions, and logged but 109 innings (mostly out of the bullpen) while experiencing his first true taste of professional baseball failure. Next he was sent back to Clark Griffith’s Washington franchise and assigned to their Springfield (Massachusetts) minor-league affiliate, where he enjoyed something of a resurrection with an 18-8 1940 performance for a sub-.500 Eastern League club (Class A). Then came a final deal – one that sent him packing for Cincinnati. The Reds farmed him out to International League Syracuse, for whom he would enjoy a true career year in the wartime season of 1943.

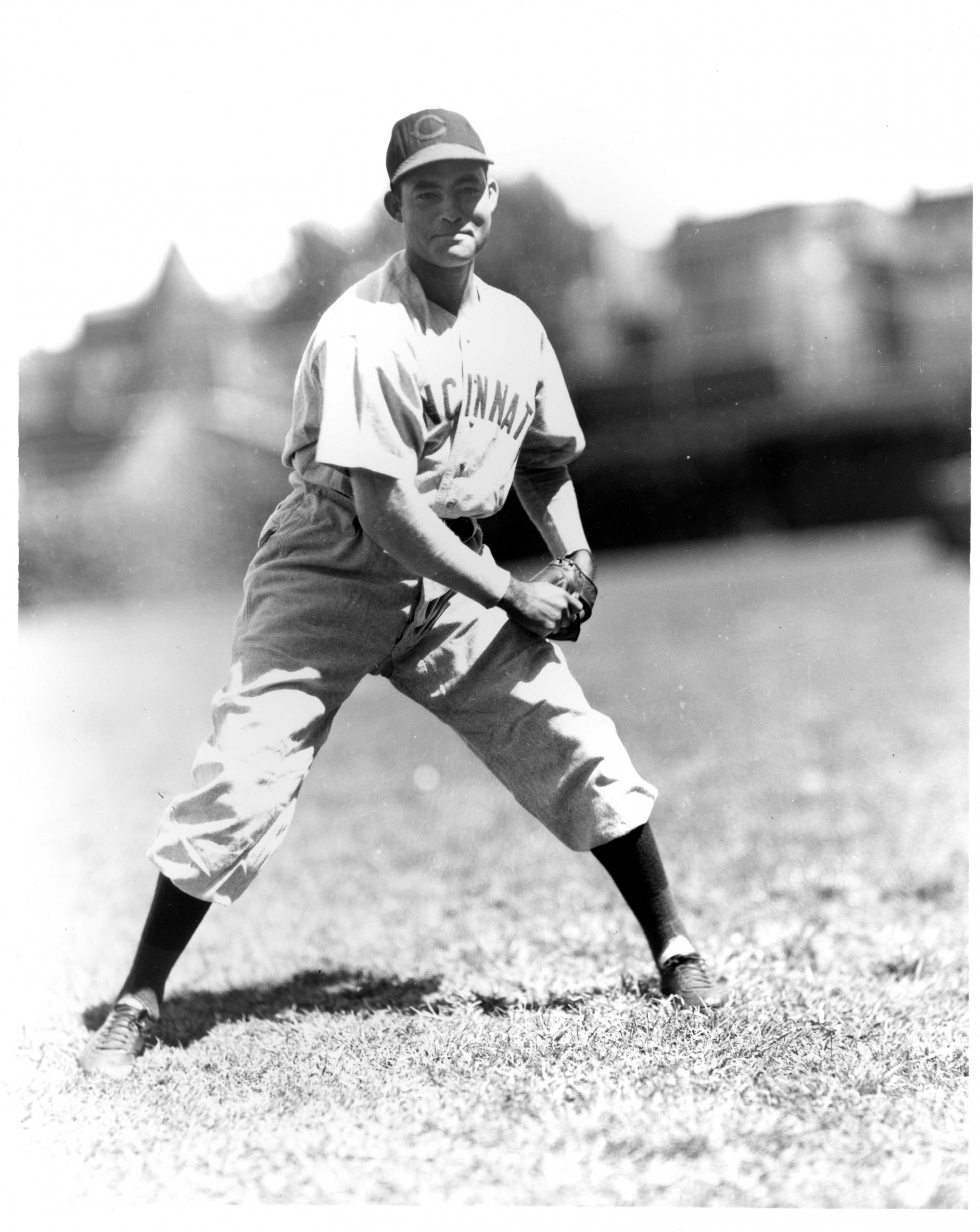

If the wartime player shortages likely played at least a partial role in the Reds’ decision to rush their Cuban prospect into major-league service, that fortuitous promotion also must have had something to do with the eye-catching 1943 successes in Syracuse. With the International League’s third-place club the right-hander enjoyed a phenomenal year, winning 21 games (not 25 as González Echevarría and others have reported), posting a stellar 1.99 ERA (the league’s second best), and logging an exhausting 276 innings of work. The following spring he would be a similarly successful if short-lived fixture with the big club in Cincinnati. He made his first big-league appearance (a start) on April 20 at Crosley Field, a solid complete-game five-hit effort producing a 2-1 victory over the Chicago Cubs. He tossed a second complete-game victory two weeks later during a 10-4 romp over the same Chicago team at Wrigley Field. The first loss for the Cuban rookie came on May 7, in ironically one of his best pitched games of the entire summer. Despite again going the distance at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, de la Cruz fell victim to a sixth-inning solo shot off the bat of Cardinals left fielder Danny Litwhiler in a three-hit, 1-0 setback.

The single big-league campaign of 1944 was seemingly solid enough – even by tarnished wartime standards – to earn more than a single shot at glory in “The Show.” De la Cruz (either 30 or 33 years of age at the time) won nine games with a solid club (third-place finishers behind St. Louis and Pittsburgh) and logged enough starts (20) and innings (191?) to lose another nine decisions. He was one of the better hurlers in the Reds’ diminished camp (trailing only Clyde Shoun in mound appearances), but his nine wins ranked only sixth on a club that featured five double-figure winners. Despite the respectable first-division finish, the Cincinnati club was hardly a contender down the stretch, trailing the eventual winners by 16 games. De la Cruz himself finished quite strong, winning his final three decisions in the waning weeks of September. And his overall numbers were proficient enough to place him in the league’s top 10 in four often-overlooked categories (BB per 9 IP, Hits per 9 IP, Walks/Hits per 9 IP, SO/BB ratio).

The year’s highlight for de la Cruz came on the road September 16 versus the second-place Pittsburgh Pirates. After yielding a run-producing single to left-handed-hitting outfielder Frank Colman in the opening frame, de la Cruz breezed through the eight remaining innings unscratched in the 2-1 Forbes Field victory (the first of three straight triumphs at season’s end). The late-season victory streak brought the rookie’s season ledger back to .500. But far more significant, the sterling one-hit effort in Pittsburgh was a landmark – the first-ever one-hitter by a Latin American big leaguer. The Saturday afternoon near-masterpiece did include four walks (two in the initial frame) balanced by only three strikeouts, and therefore one might argue that de la Cruz’s May 7 1-0 loss (on three hits, including Litwhiler’s fateful deciding homer, but no free passes) was an equally brilliant effort.

When the ledger closed in September on the Reds’ so-so campaign it also closed on de la Cruz’s big-league career. Why was it all over so quickly? Was the Cincinnati management no longer willing to push the racial barrier issue with its white players now about to return from wartime duty? Had the Cuban hurler’s main attraction been simply that he was at least temporarily exempt from the US military draft? Other marginal ballplayers (a few of them foreigners) had begun appearing in Cincinnati for that very reason.13 Or was it that de la Cruz was in fact drafted by the US military in the winter of 1944-45 but then elected to enlist in the Cuban army instead?14 In the end it seems that neither issue – racial profile or draft status – was a factor. It was apparently simply a matter of the Cuban receiving a much better offer from other quarters to sell his now-proven talents to Jorge Pasquel’s rival Mexican League.

While working his way toward the short sojourn in the majors up North, de la Cruz was also enjoying a not insubstantial winter-league career back home in Cuba that was split between the Marianao, Habana, and Almendares teams. His 13-year domestic-league tenure – a span equaling that of Cooperstown Hall of Famer José de la Caridad Méndez – would produce nearly as many wins as the more celebrated Diamante Negro. But the overall ledger (a .477 winning percentage compared with Méndez’s all-time-best .731) would be far less impressive. De la Cruz posted six winning seasons and the highlight came with a 9-4 ledger for champion Almendares in 1944-45 (the winter lodged between his year in Cincinnati and his flight to Mexico). He would eventually hold down a number of top rankings on the all-time Cuban League list – most notably second in losses (78), third in games pitched (252), and a top-10 slot in complete games (ninth with 73). Twice (1936 and 1940) he paced the circuit in total appearances and he also led twice (1935 and 1944) in complete games. He was a single-time league leader in wins (1935), innings pitched (also 1935), and ERA (1945).

While working his way toward the short sojourn in the majors up North, de la Cruz was also enjoying a not insubstantial winter-league career back home in Cuba that was split between the Marianao, Habana, and Almendares teams. His 13-year domestic-league tenure – a span equaling that of Cooperstown Hall of Famer José de la Caridad Méndez – would produce nearly as many wins as the more celebrated Diamante Negro. But the overall ledger (a .477 winning percentage compared with Méndez’s all-time-best .731) would be far less impressive. De la Cruz posted six winning seasons and the highlight came with a 9-4 ledger for champion Almendares in 1944-45 (the winter lodged between his year in Cincinnati and his flight to Mexico). He would eventually hold down a number of top rankings on the all-time Cuban League list – most notably second in losses (78), third in games pitched (252), and a top-10 slot in complete games (ninth with 73). Twice (1936 and 1940) he paced the circuit in total appearances and he also led twice (1935 and 1944) in complete games. He was a single-time league leader in wins (1935), innings pitched (also 1935), and ERA (1945).

The biggest highlight on home soil came on January 3, 1945 (immediately on the heels of the single big-league campaign), when he tossed a masterful no-hitter, one of the few in the history of the circuit.15 The gem unfolded in La Tropical Stadium in the form of a 7-0 whitewashing of the Habana Lions, the second league masterpiece in two seasons, the sixth on record, and the fourth of the twentieth century. The opposition Habana lineup for the game, which was played in a speedy hour and 50 minutes, featured such notable rival sluggers as Roberto Estalella, Heberto Blanco, Gilberto Torres, and Chino Hidalgo. Following the memorable contest, de la Cruz hurled two additional consecutive shutouts, running up a string of 27 scoreless innings against the rival Habana club. That career-peaking no-hitter also came on the eve of de la Cruz’s transition to Mexico.

The subsequent sojourn in Mexico not only brought a large haul of pesos from Pasquel’s coffers but also a good deal of notoriety and pop-culture celebrity, including a brief stint as a radio announcer. The tall, powerful, and handsome righty was light-skinned enough to be considered a most glamorous figure and he quickly picked up a special nickname (María Félix) in honor of a beautiful and popular Mexico movie actress. But it was not all high-society fluff since successes on the ballfield in Mexico were easily a match for any off-field celebrity. There were several highly productive campaigns beginning with a 17-11 ledger (and 2.26 ERA) for the 1945 edition of the Mexico City Rojos followed by 9-6 and 11-6 seasons with the same club. He returned each summer through 1948 and built an impressive statistical résumé over the four-season span, including a 40-26 won-lost mark, a 2.60 ERA over 106 games, more than 600 innings pitched, and 16 shutouts. He developed an enduring personal friendship with Pasquel and was treated especially well by the generous and free-spending league owner. When his Cuban ace was sidelined by a pulled leg muscle near the end of an initial successful 1945 season, Pasquel continued to pay full salary to his sidelined pitcher and also picked up the full bill for treatment of the injury back in Havana.

But there would also be a huge downside to the Mexican adventure. Along with more than a dozen of his recruited countrymen, de la Cruz was eventually banned from Organized Baseball along with all the others (Americans included) who had signed on to support Pasquel’s ambitious league expansion plans. Despite the fact that de la Cruz had no further interest in stateside professional baseball, the aborted Mexican League adventure would nonetheless have a huge impact on his final two winter campaigns back in Havana. And the resulting catastrophe spawned by the short-lived Mexican League experiment – in the form of a pair of disastrous split seasons back in Cuba featuring dueling circuits of “eligible” and “ineligible” MLB players – would bring much personal sadness as well as an unexpected death knell for de la Cruz’s still-viable pitching career.

The moguls of Major League Baseball would, of course, not abide Pasquel’s brazen challenge sitting on their hands. Commissioner Albert Benjamin “Happy” Chandler was quick to ban players who had participated in the “outlawed” Mexican League, and the first ramifications of the punitive action would be most heavily felt that winter in Havana. An immediate effect was a debilitating division of the Cuban circuit into two separate leagues as direct fallout from the daring Pasquel challenge to the North American big-league monopoly. First (in 1946-47), “eligible” ballplayers who had shunned Mexico fled the established league, now playing its inaugural campaign in a new showcase downtown ballpark. A year later it was the Pasquel recruits (“ineligibles”) who had to settle for rival league status in the now largely abandoned playing grounds at historical La Tropical Park. Before it all played out over the next two winter seasons, those Cubans who had enhanced their careers in Mexico eventually found themselves languishing in an inferior rival league within their own country. De la Cruz, as one of the founders and newly elected head of the “outlaw” players’ union (Association of National League Ballplayers), eventually played an important role in organizing the new ill-fated league (the Liga Nacional housed in La Tropical for the 1947-48 winter months). And none of it turned out well either at home (in the largely failed Liga Nacional) or abroad (in Pasquel’s crumbling Mexican circuit). But first there was one final highlight season (1946-47) back on the domestic front, easily the most dramatic campaign of de la Cruz’s own dozen-year Cuban League career.

Anyone trying to make any sense of the Cuban postwar seasons of 1946-47 and 1947-48 is likely to be overwhelmed by the reigning confusion. A league whose history was often chaotic, and which found itself teetering on the brink of collapse more than once down through the years, reached a new low in the fall of 1946 on the heels of Pasquel’s Mexican experiment. Unable to entice the owner of La Tropical (beer impresario Don Julio Blanco Herrera) to upgrade his aging venue, Cuban League bosses erected a new palace of their own (originally named Cerro Stadium and still in use today as Latin American Stadium). And they also refused to heed the call of MLB to shun both Cuban and American players who had signed on with Pasquel. The result was a second league known as the Federation League playing in La Tropical and staffed by those players (big leaguers Fermin “Mike” Guerra, Gilberto Torres, and Regino Otero among them) unwilling to jeopardize their careers by playing with the banned athletes. The new league had the small advantage of playing across the island (with teams in Matanzas, Santiago, and Camagüey) and thus not restricting its fan base to the capital city alone. But in the end it was a financial disaster (one matchup was canceled when Camagüey players refused to take the field without payment in advance) and the whole operation collapsed by the middle of the year. Some of the most popular players from La Tropical (pitcher Conrado Marrero in particular) “jumped” to join the more successful Cerro Stadium circuit once the Federation League succumbed early in January.

Meanwhile de la Cruz would play a significant if not central role in the more attractive season being staged by the long-established Cuban League. As part of a strong Almendares pitching staff assembled under manager Adolfo Luque, de la Cruz enjoyed several important outings down the stretch of one of the most exciting and memorable head-to-head pennant races staged under the old Cuban winter-league system.16 With burgeoning fan support stimulated by the postwar economic boom and the showcase new stadium near the city center, popular rivals Almendares and Habana (managed by the legendary Miguel Angel González) battled to the wire with Luque’s Blues claiming the crown behind strong pitching from American Max Lanier on the season’s next to last afternoon. As the team’s fourth starter, de la Cruz did not see action in the final pennant-clinching three-game sweep of Habana, but he did win a number of crucial contests in the Blues’ come-from-behind stretch run and his six wins over the winter trailed only teammates Lanier and Agapito Mayor. It was rumored that de la Cruz would be Luque’s choice to pitch the final pennant-deciding match but Lanier was handed the ball instead on one day’s rest and the decision forever strained the future relationship between de la Cruz and the fiery Luque.

A year later the Cuban scene became more chaotic still. In the intervening months MLB officials had finally persuaded league bosses in Havana to join the ranks of Organized Baseball and thus to enforce the still-existing ban on Mexican League signees. The immediate result was the banning back home of some of the top Cuban stars, including de la Cruz, Bobby Estalella, Ramón Bragaña, and Lázaro Sálazar (along with such notable Americans as big leaguer Sal Maglie and Negro leaguers Ray Brown and Leon Day).

Taking quick action, de la Cruz and Nap Reyes formed a union of “outlaw” ballplayers and put together a new league that would be called the Liga Nacional and banked mainly on the reputation and following of many former Cuban League stars and the tradition of the historical La Tropical playing grounds. The situation was completely reversed from the previous season, with the banned players operating in La Tropical and the traditional league playing in El Cerro and now manned only with the ballplayers sanctioned by Organized Baseball. Placed on the roster of the Liga Nacional club called Alacranes or Scorpions (and appropriating the colors and logo of the popular Almendares Blues), de la Cruz never appeared in game action (apparently sidelined by a nagging arm injury and his now acrimonious relationship with Luque), and concentrated instead on his administrative duties with the new union. In the latter capacity he was quickly embroiled in controversy when he apparently broke an earlier pledge to pay all union players an equal salary. It was apparently de la Cruz’s under-the-table bonus payments to select Cuban and North American stars that caused some “outlaw” players (like catcher Andrés Fleitas) to abandon the union and return to the established league playing in El Cerro.

Once again the secondary “rival league” floundered – despite its roster of many better-known stars – and couldn’t complete on equal footing with the more traditional circuit. For the second year running, the league housed in La Tropical was plagued by severe financial woes and sapped by bitter acrimony and thus rapidly collapsed in ruins by season’s end. The Santiago club (one of four) folded after only 21 contests and despite the presence of headliner figures like big leaguers Maglie and Lanier, iconic managers Luque and Reyes, and living legends like the elder Luis Tiant and slugging Roberto Ortiz. The circuit struggled to complete its 91-game calendar. Many of the disillusioned players received no more than a token percentage of their promised salaries and not surprisingly it would be primarily de la Cruz, the most visible union leader, who would soon be receiving the brunt of their understandable wrath.

The sad outcome of all these machinations would produce the darkest moments of de la Cruz’s roller coaster life. Returning to Mexico for a final 1948 summer season (this time with a new club in Veracruz), the once popular Cuban was suddenly shunned and even fully ostracized by numerous Havana teammates and opponents who had been loyal sidekicks only a few months earlier. Some of the disillusioned Liga Nacional players who had been shortchanged by the collapse of the “ineligibles” league playing at La Tropical would now publicly point an accusing finger straight at de la Cruz once they all arrived back in Mexico. On the field the disillusioned Cuban suffered his worst Mexican campaign (3-3 and a 3.43 ERA) and away from the ballpark his popularity vanished entirely. It was a cruel blow and one that apparently shook de la Cruz to the core. He returned to his native Havana by summer’s end as a thoroughly defeated and dejected man. Only in his mid-30s and with his playing days brought to a harsh and unexpected end, the once dashing figure had been reduced to a broken recluse without an apparent future.

But fortune is not always quite such a cruel mistress. If Lady Luck – often an odd mixture of painful bad luck spiced with contrasting spates of rare good fortune – had earlier seemed to play a central role in the on-field career of Tomás de la Cruz (particularly the wartime circumstances that brought him to “The Show” for such a brief span) it was nothing compared to the mixture of rare contrasting positive and negative twists and turns the former ballplayer would experience on the heels of his playing career. Not merely once but twice in the succeeding year he would walk off a winner the Cuban lottery – to the tune of a then rather large fortune amounting to a $125,000 windfall – and this reversal of fortune suddenly made him a very wealthy man in the free-wheeling Cuba, still controlled by strong-armed dictator Fulgencio Batista.17A very large accompanying downside nonetheless was the fact that the star-kissed jackpot winner was unknowingly now living on borrowed time and would only have a bit more than a decade remaining to enjoy his new-found treasures.

With his unexpected longshot winnings de la Cruz bought an apartment complex in central Havana, as well as a brand new status-symbol Cadillac convertible, and was soon living lavishly from the rental income produced by his newly acquired piece of prime real estate. The charmed ex-ballplayer was quick to attribute his reversals of fortune to the Afro-Cuban deity (orisha) Santa Bárbara, a fixture of the island’s wildly popular Santeria religion. He constructed an elaborate altar to his patron Santeria orisha in his home and signaled further gratitude by naming his new gold-mine apartment building Edificio Bárbara.18 Little else, however, is known about his private life once the door was closed on professional baseball. But luck once more quickly displayed its contrasting “other face.” On September 6, 1958, the 44-year old (or possibly he was 47) high-roller was felled suddenly by an apparent massive heart attack. His burial site in Havana, like so much about his origins, remains a dark mystery, but we are nonetheless certain that he does not lie alongside other celebrated stars of the early twentieth century in the Vedado neighborhood’s Cristóbal Colon Cemetery crypt erected at midcentury by the Cuban Federation of Former Ballplayers.

In its act of death the workings of odd fate again touched de la Cruz like something of a fickle two-faced goddess. Tragically he was felled by a weakened heart that prematurely robbed him of his remaining years even though it had never compromised his baseball achievements. But his passing came only four months short of Fidel Castro’s final revolutionary triumph of January 1959. Had de la Cruz lived on, his new-found wealth and prestige as a privileged Havana apartment owner would likely have come to just as quick and unceremonious an ending as had his big-league tenure a decade and a half earlier. Once again he would have been cruelly robbed by external circumstance of successes he had achieved against truly rare odds. Within 24 months the professional Cuban League where de la Cruz built much of his athletic legacy, as well as the gambling industry and lottery which handed him his new found fortune – even the stature and financial security he enjoyed as a Havana landlord and private property owner – all were washed away in a flash under the new socialist regime that accompanied the Communist-styled revolutionary movement orchestrated by Fidel Castro.

The impact of Tomás de la Cruz as a racial pioneer is certainly not insignificant. But the work of the game’s numerous chroniclers would eventually conspire, even if unintentionally, to bury his achievement as it did that of several other groundbreaking Afro-Cuban and Afro-Latino compatriots. Revisionist history has assigned the star role of baseball’s integration movement in North America to one man alone and that man is Robinson (unless of course one also considers co-architect Branch Rickey). And the 1940s wartime era in which the mulatto Cuban pitcher flashed his talents was also a likely contributing factor to the diminishing of a substantial baseball career. Big-league baseball’s pre-1947 racial politics, Jorge Pasquel’s failed plot to upset the Organized Baseball applecart, the chaos surrounding a foundering domestic league in his native Cuba, a partial decade of “replacement” player baseball now relegated to something less than full legitimacy, and a final act of God in the form of a sudden premature physical demise – a rather remarkable string of odd twists and turns all contributed to obscure one of the more productive single-season-only careers found anywhere baseball history.

This biography appeared in “Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II” (SABR, 2015), edited by Marc Z. Aaron and Bill Nowlin. It also appeared in “Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe” (SABR, 2016), edited by Peter C. Bjarkman and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Bjarkman, Peter C. A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2007).

Bjarkman, Peter C. “Cuban Blacks in the Majors Before Jackie Robinson” in Peter C, Bjarkman, editor, The (Inter-) National Pastime 12: An Olympic-Year Appreciation of Baseball Around the Globe (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1992), 58-63.

Campello, F. Lennox. “Before El Duque There Was Luque and Before Robinson There Was Estalella,” internet blog essay on capell.tripod.com.

Figueredo, Jorge S. Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2003).

Figueredo, Jorge S. Cuban Baseball, A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2003).

González Echevarría, Roberto. The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Kreuz, Jim. “Jackie Robinson Wasn’t the Dodgers First Choice,” Presentation at the Society for American Baseball Research Convention (Houston, Texas), August 2, 2014.

Lieb, Fred. Baseball As I Have Known It (New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan Publishers, 1977).

Peterson, Robert. Only the Ball Was White: A History of Legendary Black Players and All-Black Professional Teams (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992) (reprint of classic 1970 edition).

Torres, Angel. La Leyenda del Béisbol Cubano, 1878-1997 (Miami, Florida: Review Printers [self-published], 1996).

Wilson, Nick C. Early Latino Ballplayers in the United States –Major, Minor and Negro Leagues, 1901-1949 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2005).

Notes

1 Nuxhall made his single June 1944 appearance in Cincinnati (two-thirds of an inning) 49 days short of his 16th birthday, thus becoming the youngest twentieth century big leaguer ever, and then disappeared from the majors until his reappearance at age 23 in 1952. It is worthy of note in the context of this article that Nuxhall’s ill-fated debut (June 10 in an 18-0 loss to St. Louis) overlapped the same season marking de la Cruz’s brief stopover in Cincinnati. Gray (whose true birth-certificate name was Pete Wyshner) also logged a single campaign (only one summer later in 1945) with the junior-circuit Browns and his handicapped outfield play caused considerable clubhouse dissension; several St. Louis teammates were later quoted as blaming Gray for costing their team a repeat American League pennant. Newhouser at the height of the war years (1944 and 1945) became the first pitcher to capture consecutive league MVP awards and although he eventually won 200-plus big-league games he never again matched his three straight 20-win campaigns (that included a hefty 29 victories in 1944 and an equally noteworthy 25 a year later).

2 The careers of Luque (the first Latin American big-league star) and Marrero (MLB’s oldest alumnus when he died two days short of his 103rd birthday in April 2014) are both covered at length in earlier-published SABR Biography Project essays on two of Cuba’s most distinguished baseball icons.

3 A complete listing of these crossover Cubans (those who served in both the big leagues and on the Blackball circuit) is provided in Chapter 6 of A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006 (see page 134). The inventory of 16 includes (before 1944) Rafael Almeida, Armando Marsans, Miguel Angel González, Jacinto Calvo, Angel Aragón, Adolfo Luque, Emilio Palmero, José Acosta, Pedro Dibut, Ramón (Mike) Herrera, Oscar Estrada, Sal (Chico) Hernández; and (after 1944) Orestes Miñoso, Rafael (Sam) Noble, Francisco Campos, and Ricardo Torres. The bulk played in Blackball leagues with either the New York Cubans or Long Beach Cubans, but all organized league and barnstorming Negro League clubs maintained a much looser definition of racial distinctions.

4 The saga of Cubans and other Caribbean islanders sneaking through the sometimes porous boundaries of Organized Baseball’s “gentlemen’s agreement” is recounted in some detail in an article for SABR’s The National Pastime (Volume 12, a special issue published as The Inter-National Pastime in recognition of the 1992 Olympic Games) entitled “Cuban Blacks in the Majors Before Jackie Robinson.” These same details are elaborated on still further in Chapter 10 (“Tarzán, Minnie and El Duque – Cubans in the Major Leagues”) of A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006.

5 F. Lennox Campello in his blog essay on early Afro-Cubans in the big leagues rightly points out that Estalella possessed obviously African features but would not have been called “black” in Cuba but rather mulatto or “jabao” (translated literally as “high yellow” and used in Cuba to describe light-skinned Afro-Cubans). Estalella’s Miami-born grandson Bobby Estalella would also enjoy a journeyman big-league career as a catcher with the Phillies, Giants, Yankees, Rockies, Diamondbacks, and Blue Jays (1996-2004) long after skin tone ceased to be an issue in the national pastime.

6 As the first Puerto Rican to reach the majors Bithorn became enough of a local icon that San Juan’s main baseball stadium (and site of opening-round games for three World Baseball Classic events) still bears his name. An arm injury after World War II service cut short his postwar baseball sojourn (only 12 more decisions with both Chicago big-league clubs in 1946 and 1947) and the ill-fated athlete eventually met a tragic fate when mysteriously shot to death by a Mexican policeman in late 1951 or early 1952 (details remain unclear) during a visit to his mother in the town of El Mante.

7 Writing in Baseball as I Have Known It (1977, 260), Lieb remembered 30 years later that the black dancer he crossed paths with in St. Louis explained that her mother and Bithorn’s mother were indeed sisters. He also reports he believed at the time that the meeting with the dancer had been actually orchestrated “to tell me something” (given his advantageous position in the sporting press corps) since “it had been rumored among baseball writers and in clubhouses when Bithorn came up in 1942 that he was part Black.”

8 Another wrinkle on this theme was the phenomenon of American blacks passed off as Cubans on the barnstorming circuit to add to the ticket-selling potential of exotic island stars. One documented case involved the Babylon Argyle Hotel (Long Island) waiters who in 1885 transformed into the Cuban Giants playing out of Trenton, New Jersey. Robert Peterson (Only the Ball Was White, 36) quotes Sol White as telling Esquire magazine that when the Babylon club went on the road after their summer hotel duties “they passed as foreigners – Cubans, they finally decided – hoping to conceal the fact that they were just American hotel waiters, and talking a gibberish to each other on the field which, they hoped, sounded like Spanish.”

9 Robert Peterson details the incident and the outrage it caused among American League club owners (especially Charles Comiskey) in the pages (54-55) of his classic Only the Ball Was White (1970). The subject of McGraw’s quickly aborted if noble experiment was Chicago Columbia Giants skilled infielder Charles Grant (an obvious African-American whom McGraw attempted to disguise as a full-blooded Cherokee), who was at the time employed as a seasonal bellboy at the Hot Springs Eastland Hotel, where the Orioles were maintaining spring quarters. Peterson cites as his source the earlier account of the incident found in Lee Allen’s The American League Story (1965).

10 Hemphill’s clever plot has fictional Sally League manager Stud Cantrell bolstering his weak-hitting Graceville Oilers with slugging Negro catcher Joe Luis Brown. Cantrell passes off the unacceptable black recruit as José Guitterez Brown, just off the banana boat from Venezuela. To management and fans starved for winning baseball, a little flirtation with the “gentlemen’s agreement” might indeed be okay, provided that the swarthy ballplayer in question could pass as a “foreigner” and hit well enough to distract attention from the hue of his skin. On more than one occasion (as with Bill Veeck’s midget Eddie Gaedel in St. Louis, for example) baseball reality has followed meekly a full step behind baseball fiction. The history of the national pastime between the close of the Deadball Era and the demise of the “gentlemen’s agreement” is replete with more than one incident of big-league management passing off dark-skinned Latinos as “Cubans” or Castilians. Even well after Robinson, the late-integrating Philadelphia Phillies would disguise 1957 starting Afro-Cuban shortstop Humberto “Chico” Fernández (just acquired from Brooklyn) as merely a Cuban and only admitted to becoming the National League’s last-to-integrate club seven days later with the appearance of African American infielder John Kennedy. For years historians wrongly attributed to Kennedy the role of Philadelphia integration pioneer that more properly belonged to Chico Fernández.

11 Rickey’s reputed plot (both its historical basis and many apocryphal elements) to seek out and sign Silvio García was explored in great detail in an unpublished paper presented by Jim Kreuz at the 2014 SABR National Convention in Houston.

12 While González Echevarría provides an important outline of de la Cruz’s career, he does quite possibly err in reporting both the birth and death dates for the Cuban pitcher. It is the year and not the calendar date that remains in dispute, with González Echevarría offering 1914 while usually reliable Baseball-Reference.com has the year as 1911. Working from Cuban newspaper sources, both González Echevarrá and Jorge Figueredo settle on 1914 and the sources for their decision would argue strongly that they have it correct. Baseball-Reference.com and Figueredo both agree on a date of September 6, 1958, for the pitcher’s demise (12 days before he would have turned 44, or 47). But González Echevarría is again at odds here, claiming in a lengthy footnote that de la Cruz’s “luck ran short … when he died young in 1960.”

13 Lee Allen reports in his 1948 Putnam Series history of the Cincinnati ballclub that by 1944 the manpower situation was so bad that GM Warren Giles “was induced to sign players who would have been given no consideration under normal conditions. One was Jesus (Chucho) Ramos, an outfielder from Venezuela, who was recommended by letter and who arrived without having been scouted.” (cf. Allen, The Cincinnati Reds, 293-94) Allen makes no mention of de la Cruz and his suggestion on the following pages that the 1945 season was one in which “the quality of major league baseball reached its all-time low” would seem to work against any idea that an improved talent pool could explain de la Cruz’s early departure.

14 John Virtue (South of the Color Barrier, McFarland, 2008, 118) suggests with reason that the fact that US-resident Cubans, although not American citizens, were subject to the military draft during the war’s late stages may well have been one potent factor in motivating a handful of Cuban ballplayers (including big leaguers de la Cruz, Roberto Estalella, Roberto Ortiz, Chico Hernández, and Tony Ordeñana) to accept Pasquel’s offers of lucrative Mexican League deals in the spring of 1945.

15 The pre-revolution Cuban winter league provided only a scarce six no-hit games over 73 seasons of varying lengths (about one per decade on average). By contrast the post-revolution National Series has witnessed 53 such gems across its 53 completed campaigns (an average of precisely one per season).

16 González Echevarría, recalling favorite childhood memories, would tout this as the peak season of Cuban baseball history. But of course for that particular expatriate author, Cuban baseball history is interpreted as comprising only pre-Castro years, since in his biased view (like that of so many Miami or US-based exiles) the legitimate Cuban baseball story largely ended with the arrival of the new Communist regime. While it might be true that the 1946-47 season saw an uptick in fan enthusiasm brought on by the end of the war, it was also apparent that the two immediate postwar winter seasons witnessed a once proudly independent Cuban circuit falling under the control of Organized Baseball interests (as González Echevarría himself details). Some might argue that Cuban baseball did not reach its true apogee until several decades after Castro’s revolution instituted a new National Series baseball divorced from the clutches of Organized Baseball.

17 González Echevarría (The Pride of Havana, 409, footnote 5) provides details on the odd lottery winnings. Such commonplace street betting was a passion in Cuba of that era and de la Cruz maintained his own favorite lottery-ticket vendor (a man known only as “Checo”) who (according to the popular story) practically harassed the down-on-his-luck former pitcher into purchasing a ticket that proved to hold the top $100,000 prize. Only a few months later de la Cruz struck pay dirt again in a similar fashion, this time to the reported tune of an additional $25,000.

18 The scanty details about the ballplayer’s death, as well as the account of his lottery winnings and subsequent lifestyle are provided by González Echevarría (The Pride of Havana, 409, footnote 5). Devotion to Santeria may be another signal of de la Cruz’s own Afro-Cuban heritage, to which González Echevarría makes numerous references throughout his book. González Echevarría reports in the same footnote entry that de la Cruz had apparently been considering a return to baseball pitching as late as 1950, but his reported $1,000-plus monthly take in rental income made him one of the most fortunate among current and former island ballplayers of his era. The few Cubans in the big leaguers in the early 1950s (like Miñoso, Conrado Marrero and Sandalio Consuegra) were earning baseball salaries that barely matched or fell short of de La Cruz’s income as a Havana landlord.

Full Name

Tomas de la Cruz Rivero

Born

September 18, 1911 at Marianao, La Habana (Cuba)

Died

September 6, 1958 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.