Vedder Sitton

Grantland Rice called it “The Greatest Game Ever Played in Dixie.” He was referring to the September 19, 1908, showdown between the New Orleans Pelicans, tossing their 39-year-old ace, Ted Beitenstein, and the Nashville Volunteers. Nashville manager Bill Bernhard bypassed his more experienced pitchers and sent Vedder Sitton to the hill. Sitton had begun the season with Jacksonville in the Sally League and had only been with the Vols for a month. The spitballing Sitton shut out the Pelicans on three hits. In the seventh inning, he kept a rally alive with an infield single. Two batters later a bases-loaded single scored the runner from third. Sitton, trying to score from second, was cut down at the plate by a throw from Bris Lord.1 The game ended 1-0.

Grantland Rice called it “The Greatest Game Ever Played in Dixie.” He was referring to the September 19, 1908, showdown between the New Orleans Pelicans, tossing their 39-year-old ace, Ted Beitenstein, and the Nashville Volunteers. Nashville manager Bill Bernhard bypassed his more experienced pitchers and sent Vedder Sitton to the hill. Sitton had begun the season with Jacksonville in the Sally League and had only been with the Vols for a month. The spitballing Sitton shut out the Pelicans on three hits. In the seventh inning, he kept a rally alive with an infield single. Two batters later a bases-loaded single scored the runner from third. Sitton, trying to score from second, was cut down at the plate by a throw from Bris Lord.1 The game ended 1-0.

The game was played at the Sulphur Dells in Nashville. The victory gave the Vols a 75-56 record, good for a .573 winning percentage. Sitton wowed the crowd of over 10,000 with his performance. When he struck out the last two batters, thousands of fans poured onto the field. The crush of fans rushing at him scared Sitton, with the police protection unable to halt the throngs. The fans “lifted him (Sitton) into the air and women tried to kiss him and several hundred men tried to shake his hand at one time.”2

Born September 22, 1881, Charles Vedder Sitton3 was the second of four children born to Henry P. and Amy (Wilkinson) Sitton in Pendleton, South Carolina. Known as Vedder to friends and family, he was most often called by that name in contemporary newspapers, although it was sometimes misspelled Vetter. He also was called C.V. more often than Charles or Charlie. His siblings were James, Phil, and Ella. The Sittons were longtime residents of Pendleton. His grandfather, James, had been a coach maker with an estate valued at $100,000 in 1860. His father ran a hardware business and uncle Augustus was a cotton manufacturer. Wealthy Carolinians had built summer homes in the Pendleton area since the early 1800s. Pendleton enjoyed a reputation as the home of refined and mannerly citizens; politician and statesman John C. Calhoun had a home close to town. The area was spared most of the ravages of the Civil War; the Pendleton Woolen Mills even began business in 1863, in the midst of the war years.

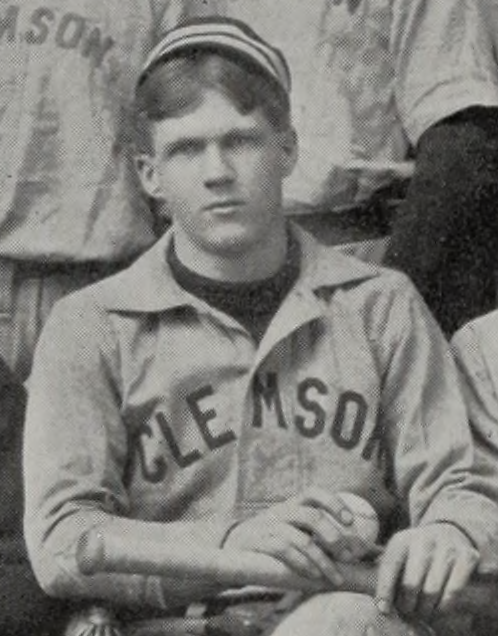

As the son of a well-to-do family, Sitton was sent off to school. He traveled four miles northwest to Clemson College. He enrolled in 1899 and was a student until 1904, but does not appear in the school’s graduate rolls. As a boarding student he did not technically live in Pendleton and when the census was taken in 1900 he was not included with the rest of the family. Sitton left Clemson and entered the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he eventually entered Medical College, but did not graduate.

Sitton grew up playing baseball, as the towns in his area played against each other and he undoubtedly had ample opportunity to refine his skills. His first collegiate appearance on the mound came on March 28, 1901, when he shut out Auburn, 9-0. His coach in both baseball and football at Clemson was John W. Heisman. In 1901, Sitton’s repertoire was a fastball, curve, and change-of-speed. Around this time, major leaguer Jack Chesbro gained fame with a spitball. By the end of his college career, Sitton had mastered the art of throwing the salivary sphere.

College baseball teams in the early 1900s scheduled many fewer games than they do nowadays. Clemson went 10-2-1 in 1901, 9-3 in 1902, and 9-1 in 1903. Sitton’s record in those three seasons was 5-2, 7-2, and 6-0. In 1903, he also played outfield. When playing outfield he batted sixth, but when pitching he batted leadoff. Against Mercer on April 13, he stole two bases and struck out ten on the way to a 5-3 win. On April 26, he tossed a one-hitter versus South Carolina winning, 3-1. Many scribes felt that Clemson was the best team in the South in 1903.

Sitton actually gained much more notoriety on the football gridiron than the ball diamond. The Atlanta Constitution named him to its 1903 All-South squad. Besides his offensive talent, the paper noted, “… on defense [Sitton] is one of Clemson’s strongest players.”4 Coach Heisman was a football innovator when the game was in its infancy: The forward pass was not yet legal, the field was 110 yards long, touchdowns and field goals were both worth five points, and an extra point was one point. Offensively, a team either tried to ram the ball down the field or attempted misdirection plays that involved laterals and even backward passes.

Sitton played end, which meant he was involved in various end-around runs and reverses. Against Georgia Tech on October 18, 1902, he had touchdown runs of 80, 85, and 50 yards in the first half. Exhausted, he left the field and rested the remainder of the 44-5 victory. On November 15 versus Auburn, he scored from 30 and 35 yards in a 16-0 victory. The 1903 game with South Carolina ignited the long-running rivalry between the two schools that still survives today. The Gamecocks won, 12-6, but Sitton scored the Clemson touchdown on a 30-yard run.

Sitton closed out his collegiate career at North Carolina University where he was an end in football and spitball pitcher in baseball. In fact, he was elected president of his first-year medical class and the local paper listed him as “Spitball Sitton.”5 Sitton did not complete his medical studies, but that did not stop writers in later years from occasionally dubbing him “Dr. Sitton” in their game stories.

In the summers, Sitton played with a variety of semi-pro teams, since good pitchers are always in demand. In 1902, he played with Anderson, which was 14 miles from home. He made a single appearance with Batesburg, South Carolina, which necessitated a train ride of 100 miles. He also played with a Tampa, Florida team. In 1903, Sitton joined the Augusta Students, in what would become the South Atlantic League a year later. The Students were the class of the league compiling a .796 winning percentage. Sitton won 14 of 15 starts and allowed just over seven hits per game. At the plate he batted .221.6

Newspapers were filled with stories about where Sitton would play when he went professional in 1904. At various times he was linked to Atlanta, Birmingham, Jacksonville, and Columbia. Vedder did not play for Clemson in 1904, possibly because he violated his amateur status playing with Augusta. His brother, Phil Sitton, did play for Clemson starting in 1904. In July, Vedder joined Spartanburg in the newly-formed Carolina Inter-State League. The league rosters were made up of collegiate players. He opened the season by tossing a no-hitter against Hendersonville on July 11. He was joined soon after by Phil.

The pennant race in the four-team circuit was between Spartanburg and Asheville. The Asheville newspaper took glee on August 11 when the local team beat “Big Sit” and “Little Phil” in a doubleheader.7 Spartanburg shook off the defeats to win the pennant the next week.

Sitton pitched for the University of North Carolina in 1905. His finest day came May 3 in a doubleheader versus the University of Virginia. In the opener, he struck out 17 and hurled a one-hitter. In the second game he tossed a four-hitter and launched a home run in the fifth for the victory.8 The Charlotte Observer said that he won 8 of 12 starts and struck out 134 batters.9

Sitton had reportedly signed with Jacksonville in 1904, but never reported. He appeared on Jacksonville’s reserve list in 1905, and because of the reserve clause, Sitton was obligated to whichever team held his rights. If he wanted to play above the semi-pro level, it would have to be with Jacksonville.

In 1905, he played in a Vermont league (possibly the Northern New York League) as “Smith.” In June 1906, he started the season with Ottawa, Canada, in the Northern League.10 He chose to end his nomadic semi-pro lifestyle and finally joined the Jacksonville Jays of the South Atlantic League on July 19, 1906. His first action came on July 20 against Charleston in a lackluster performance that he lost 6-2.

Five days later headlines like “Charlie Sitton is in a Fix” screamed at readers.11 Before he was sent to the mound on July 24, Sitton was questioned by Jacksonville management if he intended to give his best effort. He indicated that he had reported to Jacksonville only to get his release and be free of the club’s reserve hold on him. He was immediately suspended. His punishment would be that he had to ride the bench without pay for the season. In addition he was fined $100, which if unpaid would result in being blacklisted.12

In 1907, the Jays hired Dominic Mullaney as their manager. Mullaney collected a veteran squad and convinced Sitton he would be an integral part of a strong team. Sitton showed little rust from his forced inaction the previous year, quickly winning a spot in the Jays’ rotation. Unfortunately, Sitton pitched with bad luck. He found himself frequently matched with champion Charleston’s Bugs Raymond, the league’s finest twirler. In one stretch against Raymond, he dropped three one-run decisions. Sitton also had more than his share of tie games and extra-inning affairs. He ended the season 16-14 for second-place Jacksonville.

He was drafted by Nashville, but in the spring was optioned back to Jacksonville. The Jays were still led by Mullaney and retained pitcher Jack Lee and four position players from the previous season. The new roster clicked immediately. By the end of April, Jacksonville was 15-3. Except for a four-hit shutout loss to Phil Sitton on April 24, they had dominated the opposition.

Phil Sitton struck again on May 6, this time in a duel with his older brother. Jacksonville dropped a 2-1 game to Augusta when Phil gave up fewer hits than Vedder (6-8) and struck out more batters (9-7). Standing at 30-11 when June began, Jacksonville added another pitcher and went with a five-man rotation. On August 1, Sitton tossed a no-hitter against Macon and ran the club’s string to 47 consecutive shutout innings.13 The streak ended at 60 on August 3 when they bested Charleston, 5-1.

Jacksonville had the pennant race under control, but hit a bump on August 7 in Augusta. Phil Sitton tossed both ends of the doubleheader for the Tourists and won, 3-0, 6-0. Vedder missed the show, as the Nashville Volunteers in the Southern Association had called him up. The Sally season ended on August 22, but not before Phil tossed a second no-hitter. He led the league with 19 victories, while Vedder, at 17-5, had the best winning percentage, .773. The Sitton brothers were named to a variety of league all-star squads. Jacksonville ran away with the pennant at 77-34, whereas Savannah finished second at 64-45.

Sitton made his presence known immediately with the Vols. He beat Atlanta on August 7, 2-1, and struck out eight. He beat Atlanta again before dropping three consecutive games. A 1-0 victory over New Orleans on September 1 was a glimpse into the future. He tuned up for the season finale with a September 11 one-hitter versus Little Rock and a three-hit win over Mobile. He closed out 1908 with a 17-5 mark at Jacksonville and a 6-4 record for the Volunteers. His contract was purchased by Cleveland.

Sitton stood 5-foot-10 and weighed 170 pounds. Sources have described him as having light hair. Judging from his pictures at Clemson, they meant light brown because he certainly was not a blonde. He was judged to be “one of the cleanest-cut men in the game today.”14 By the time he joined Cleveland, his spitter was his primary pitch; he could make it break both ways, but like a knuckleball, it sometimes had a mind of its own. He also had developed a cross-fire delivery that would give a right-handed batter fits.

The Naps returned Addie Joss, Heinie Berger, Bob Rhoads, Glenn Liebhardt, and Cy Falkenberg from their 1908 team. Nevertheless they brought 42-year-old Cy Young back to town and also had rookie Lucky Wright competing with Sitton. As spring training came to a close the decision was made that Young and Joss would pitch every five days and the other pitchers would be used as needed.

Sitton saw his first action on April 24 against the St. Louis Browns. April weather in Cleveland can be harsh, especially for someone from the South. It was not an artistic game; the two teams combined for 24 hits and committed nine errors. Sitton walked five and hit a batter, but when it came time to bear down, he was up to the challenge, and the Naps won, 7-3.

Despite the performance he did not get another start until June 5 when he was sent to the hill in Washington against Walter Johnson. The weather was much nicer, but inactivity made it hard for him to get the spitter to work well. He gave up ten hits, but only three runs, and battled Johnson into the 11th inning. The Naps scored three in the top of the frame, while in the bottom half; “the home team went down before Sitton like clay pigeons before a crack shot.”15 Two weeks later he started against the Browns and won, 3-2 despite giving up 11 hits. In three starts he had surrendered 32 hits and walked ten, but at 3-0, he led the American League in winning percentage.

His next start came on June 28 in St. Louis where he was driven to the showers in the third after surrendering four runs. He made only one other start, on August 20, when the Athletics treated him the same way the Browns had. He spent the entire summer with the Blues but only saw action in 14 games, closing with a 3-2 record. On January 22, 1910, Cleveland asked waivers on eight players including Sitton.

Led by Cleveland castoffs Leibhardt (23 wins) and Sitton (16 wins), the Columbus Senators of the American Association won 88 games in 1910. However, the Minneapolis Millers ran away with the pennant by winning 107. Sitton returned to Columbus in 1911. He beat Milwaukee on April 27. The 1912 Spalding Baseball Guide lists him with two victories and no defeats.16 The other win came on May 15 against Toledo. That game was relatively uneventful except that Evangelist—and former big leaguer—Billy Sunday was hired on a one-day contract to be “field umpire.” When Sunday went behind the plate, Sitton objected and a loud heated argument ensued. Sitton protested that a “field ump” was not allowed to work the plate. Despite the dustup, the game proceeded, with Columbus winning 10-8.

On June 23, Sitton was sold to the Atlanta Crackers in the Southern Association. His return to the Association was far from successful. His old team, Nashville, crushed him twice: 11-2 and 11-3. Sporting a 2-5 record in early August, he was sold to the Columbus Foxes in the Sally League. The Foxes were first-half champions, but were scuffling in the second-half and trailed Columbia for the top spot.

Sitton looked sharp in his initial appearance, whipping Macon 2-0 on a three-hitter. Four defeats followed before he found his groove. From August 29 through the league championship series, he was a force to be reckoned with. On September 18, in the championship finals, he was called upon to relieve even though he had a sore arm. He summoned his strength and threw 6 2/3 innings of relief to give Columbus the win and the title. The Spalding Guide lists him at 4-4, but it is uncertain whether that includes his two wins in the championship series.

In mid-August the major leagues had gone on a buying spree and purchased over 300 minor leaguers designated to report later. On August 19, the Brooklyn Robins picked up Sitton and seven others. This transaction led to a protest over Sitton’s use in the championship series.

There had been a dispute over the rules in game two when the umpire forfeited the game to Columbus because Columbia was using a player who had been optioned to them in violation of league championship rules. Columbia manager Bill Clark filed a protest claiming that the Brooklyn purchase was all part of an elaborate plan to eventually return Sitton to Atlanta. Essentially, Sitton had just been “optioned,” but it was disguised to look like a sale had taken place. When informed of Clark’s conspiracy claims the league president said, “Don’t make me laugh. I have serious things on my mind.” Columbia’s chances of help from the league office were slim since the president was none other than John Heisman, Sitton’s former coach.17

Perhaps Clark knew what he was talking about, since Sitton was with Atlanta, and not Brooklyn, in 1912. He turned in a 10-10 record in 29 games. He also pulled in a handsome salary because, as a former major-leaguer, the Crackers saw him as a box office attraction. Unwilling to spend that type of money another year, the Crackers sold Sitton to the Troy Trojans in the New York State League for the 1913 season.

Sitton would work the next two years for manager Hank Ramsey in Troy. In 1913 they battled for the pennant, but finished third. Sitton tossed his second professional no-hitter on July 31. As the pitching ace, he led the squad in appearances and strikeouts. The following spring he was a holdout. Sitton was demanding $300 from Troy.18 Ramsey complained publicly that other teams in the league had offered his pitcher $325 a month.The issue was resolved and Sitton pitched Troy to a 7-6 win in the second game of the season.

Phil Sitton joined the team in June, but the brother duo did not find success. Troy finished in the second division. Vedder authored a no-hitter on July 11, beating Scranton, 1-0 in seven innings. That would be his high point because he was only 2-11 after that. As he did every winter Vedder returned to Pendleton. Each spring he trained with the Clemson team to get into shape. In 1915 his training regimen was changed when he accepted the job as coach. He guided the team for the next two seasons to records of 13-7 and 13-11-1.

In both 1915 and 1916 when the Clemson season wrapped up, he went north to pitch for the Binghamton Bingoes in the New York State League. He had become a free agent along with other Troy players because the Trojans failed to make all of their salary payments.19 His 16 wins helped the Bingoes take the pennant in 1915. They finished third in 1916 and Sitton went 14-14. There was speculation that he might be hired as the manager for 1917, but that job went instead to infielder Charley Hartman.

Sitton hung up the spikes that winter. He accepted a job with the Hercules Powder Company, manufacturers of gunpowder. He worked in Nitro, West Virginia, for the first few years where he was a foreman in the production division. Over the years he also worked at facilities in Georgia and Mississippi. He quit the company in the late spring of 1931 and moved to Valdosta, Georgia.

On September 11, 1931, Sitton borrowed a car from a friend. When he did not return the vehicle, a search party was organized to locate him. Sitton had driven out to the old fairgrounds in Valdosta and committed suicide with one shot from a pistol. What caused him to this end his life was never revealed. The body was returned to Pendleton and following a service in the Presbyterian Church he was buried in the church’s cemetery.

Sources

The Clemson Baseball Media Guide provided college stats. There had been a mystery as to which brother played baseball at UNC-Chapel Hill. Todd Dawson with the Medical College alumni group helped with the identification. Bobby Hundley of the Athletic Department and SABR member Karl Green of the Collegiate Committee also provided guidance.

Notes

1 Starting in 1911 a game narrative made the rounds in newspapers where Sitton was knocked unconscious at the plate. He had to be revived and then staggered to the mound for the next inning. Contemporary accounts make no mention of violent collision or injury.

2 Will R. Hamilton, “Nashville Wins Sothern Pennant by Only Two Points,” New Orleans Item, September 20, 1908: 10.

3 Baseball Reference and the Baseball Hall of Fame call him Carl Sitton. To date the author has found only three contemporary articles calling him Carl. Over 400 contemporary sources were found using Vedder and another 60 had C.V. The Sporting Life used Vedder 23 times and Carl once.

4 Atlanta Constitution, December 1, 1902: 9.

5 “First Year Med Officers,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, North Carolina), October 5, 1905: 1.

6 “In the World of Sports,” State (Columbia, South Carolina), August 18, 1903: 6.

7 “Sitton Boys are Victims,” Asheville Citizen-Times, August 12, 1904: 6.

8 ‘Sitton’s Great Work,” State, May 7, 1905: 5.

9 “College Baseball,” Charlotte Observer, May 29, 1905: 7.

10 Burlington (Vermont)Free Press, provided this info on June 13 and June 20, 1906.

11 Augusta Chronicle, July 25, 1906: 3.

12 “Sitton, Jays Pitcher, Benched for Season,” Macon Telegraph, July 25, 1906: 6.

13 “Macon Again Lost Doubleheader, Only Makes One Hit in Two Games,” Macon Telegraph, August 2, 1908: 6.

14 “How Vedder Sitton Appears to Them,” The Tennessean (Nashville), March 10, 1909: 7.

15 ‘Big Batting Rally in Eleventh Lets Naps Defeat Washington,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 6: 17.

16 At the present time Baseball-Reference does not list Sitton with Columbus. They have him in Montreal. The Montreal pitcher is in fact brother Phil . He was traded to the Royals by Jersey City in December, 1910.

17 ‘That Protest by Columbia,” Columbus (Georgia) Ledger, September 21, 1911: 7.

18 “Manager “Hank” on the Warpath,” The Scranton Truth, March 26: 8.

19 “Sitton Joins Bingoes,” Pittston (Pennsylvania) Gazette, June 3, 1915: 5.

Full Name

Charles Vedder Sitton

Born

September 22, 1881 at Pendleton, SC (USA)

Died

September 11, 1931 at Valdosta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.