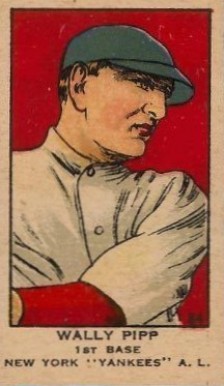

Wally Pipp

Tall, lithe-limbed and broad-shouldered, the 6-foot-2, 180-pound Wally Pipp carried himself with an unmistakable air of confidence and distinction, befitting one of the Deadball Era’s premier sluggers. Whether disembarking from a train, haggling with management over bonus money, scooping up grounders around first base, or swatting home runs, Pipp “was a high-class specimen of the ball player,” New York Times reporter James R. Harrison observed. “On and off the field, he was a prime favorite.”

Tall, lithe-limbed and broad-shouldered, the 6-foot-2, 180-pound Wally Pipp carried himself with an unmistakable air of confidence and distinction, befitting one of the Deadball Era’s premier sluggers. Whether disembarking from a train, haggling with management over bonus money, scooping up grounders around first base, or swatting home runs, Pipp “was a high-class specimen of the ball player,” New York Times reporter James R. Harrison observed. “On and off the field, he was a prime favorite.”

A harbinger for the style of play that would grip the game beginning in the 1920s, in 1916 the left-handed, free-swinging Pipp became the first player in American League history to lead the league in both home runs and strikeouts. In addition to his batting exploits, Pipp was one of the finest defensive first basemen of the Deadball Era; in 1915, he led all American League first basemen in putouts, assists, double plays, and fielding percentage.

Yet despite these achievements, today Pipp is most remembered as the man whose nagging headache persuaded him to accept a day off on June 2, 1925, a decision that — along with his poor hitting that year — led to his permanent displacement from the starting lineup by a young Lou Gehrig. For that, Wally Pipp has found a permanent place in the American lexicon, as an object lesson in the pitfalls that may await any athlete who takes a day off. As Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder Dave Roberts told reporters after leaving a game during the second inning with an injured hamstring on April 25, 2003: “I don’t want to be Wally Pipp.”

Walter Clement Pipp, the son of William H. Pipp and the former Pauline Stroeber, was born into an German-Catholic family in Chicago on February 17, 1893. He grew up in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and studied architecture at Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, before entering professional baseball. In 1912, Pipp batted .270 in 68 games for the Kalamazoo Celery Champs of the Southern Michigan League, before the Detroit Tigers purchased his contract late in the season. Though just 19 years old, and a lowly Class D player, Pipp had the audacity to ask that he be paid part of the purchase price. Not surprisingly, he was turned down.

Pipp didn’t get into any games with the Tigers in 1912, and spent the first three months of the 1913 season with Providence of the International League and Scranton of the New York State League. As Scranton reporter Chic Feldman later recalled, the youngster already had a big league air about him, arriving at the modest Scranton train station wearing a 10-gallon Texas wide-brimmed hat and appearing “sartorially neat in a gray suit, white shirt, and dark blue tie.”

Though he batted just .220 with Scranton, Pipp was recalled by Detroit and made his big league debut on June 29, 1913, going 0-for-3 against Roy Mitchell of the St. Louis Browns. In all, he appeared in twelve games for Detroit and batted just .161, which earned him a trip back to the International League. Playing for the Rochester Hustlers, Pipp was the league’s best player in 1914. He batted .314, and led the International League with 15 home runs, 290 total bases, and a .526 slugging percentage. He also belted an astounding 27 triples.

Surprisingly, or so it seemed in light of his outstanding season, on February 4, 1915, the Tigers sold him and outfielder Hugh High to the New York Yankees for $5,000 each. Though it wasn’t known at the time, the Yankees’ new owners, Jacob Ruppert and Til Huston, had actually negotiated Pipp’s sale to New York a month earlier, at the same time they bought the team.

On Opening Day 1915 at Washington, Pipp singled off Walter Johnson in his first at-bat as a Yankee. He went on to hit .246 with four home runs, one of only a handful of players to hit that many in 1915. The following year Pipp became the first player in franchise history to lead the American League in circuit clouts, batting .262 with 12 home runs. Pipp became the first in a long line of standout longball artists to play in pinstripes. “When [Pipp] swings that long heavy bat of his and gets his 180 pounds of rugged bone and muscle well behind the swing,” Baseball Magazine’s J.J. Ward observed, “that little horsehide pellet usually describes a long, beautiful arc over the outfielders’ heads.”

Tris Speaker, famous for playing a shallow center field, made an exception for Pipp. “I usually play a short field,” Speaker noted in 1917, “but of course in the case of such a batter as Pipp it would be foolish to play in.” The free-swinging Pipp also struck out 82 times in 1916, a league-high. In 1917 he cut his strikeouts to 66, but retained his home run title, hitting nine four-baggers. He batted just .244 that season, but Baseball Magazine excused this shortcoming, noting that “he makes up for the infrequency of his wallops by their length.”

The following year, Pipp slugged just two home runs, but lifted his average to .304, before the government’s “work or fight” order caused him to leave the Yankees and accept a job as a naval aviation cadet at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He returned to New York in 1919, batting .275 with seven home runs. Though those figures were in line with his previous efforts, Pipp’s status as the AL’s top home run hitter had already been supplanted by Babe Ruth, who blasted a major league record 29 four-baggers that year.

Upon joining the Yankees in 1920, Ruth quickly became the sport’s biggest star, as his unprecedented power barrage signaled the end of the Deadball Era and the emergence of the Yankees, who won three consecutive American League pennants from 1921 to 1923. By 1921 Pipp’s maturation as a hitter was complete, as the former strikeout leader fanned only 28 times in 667 plate appearances. Though completely overshadowed by Ruth’s exploits, Pipp was a vital cog in the Yankee juggernaut, batting a career-best .329 in 1922, and driving in 108 runs in 1923. In 1924, Wally led the league with 19 triples and drove in a career-high 114 runs, enough to lead the league most years during the Deadball Era, but only third-best on his own team in the offense-saturated environment of the 1920s.

Pipp’s large, agile frame also helped him become a standout defensive player. Playing deeper than most first basemen of the era, Wally used his excellent range and soft hands to anchor the New York infield. While Pipp’s fielding skills are reflected in his own numbers (during his 15-year-career, he led the league in double plays and putouts five times each, fielding percentage three times, and assists twice), his ability to reach errant throws also cut down on his teammates’ miscues. As Baseball Magazine observed, “anything that is aimed in the general direction of Pipp is pretty sure to find a safe landing place in his spacious glove.”

Throughout his life and during his baseball career, Pipp suffered recurring headaches, the result, he later explained, of a schoolboy hockey injury that had also left him with reduced vision in his left eye. He was suffering one of those headaches on June 2, 1925, and asked trainer Al “Doc” Woods for a couple of aspirins. Yankee manager Miller Huggins strolled by and suggested Pipp take the day off. “The kid can replace you this afternoon,” he said, referring to Lou Gehrig. Heading into that day’s game, the Yankees were 15-26, had lost five in a row, and were only a half game from the American League cellar. Pipp had started slowly too, batting just .244 with three home runs and 23 RBIs.

When Gehrig got his opportunity to start, he took full advantage of it. And a month later, when Pipp suffered a brain concussion, the changeover was complete. Rookie pitcher Charlie Caldwell, later the head football coach at Princeton, beaned Pipp in batting practice, and Wally spent the next two weeks at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan. When he returned, Gehrig had won the first baseman’s job, and Pipp’s role for the rest of the season was as a pinch-hitter.

The Yanks tried to trade him to several American League clubs, but couldn’t come to terms with any of them. So, after asking and getting waivers on him, they sold Pipp to the National League’s Cincinnati Reds. The Reds, still badly in need of a first baseman more than a year after the untimely death of Jake Daubert, paid what was said to be much more than the $7,500 waiver price. Once again Pipp asked that he be paid part of the purchase price, and once again he was turned down.

Now 33, Pipp bounced back with a strong performance in 1926, posting a .291 average and finishing fourth in the National League in both RBIs (99) and triples (15). A less productive year followed — .260 with 41 runs batted in — before he ended his major league career in 1928, batting .283 in 95 games. After batting .312 for the 1929 Newark Bears of the International League, Pipp retired from baseball.

He devoted the next few years to playing the stock market in Depression-era America, and even wrote a book on the subject called Buying Cheap and Selling Dear. Often jobless during these difficult times, he organized baseball programs for the National Youth Administration, tried his hand at publishing, worked as an announcer on a pre-game baseball broadcast, and even wrote scripts for a Detroit radio announcer. But money remained scarce. “We kneeled down and said prayers at night that Dad would get a job,” his son, Walter Jr., later remembered. “Those were rough times.”

During World War II, Pipp worked producing B-24 bombers at Henry Ford’s Willow Run plant near Ypsilanti, Michigan. After the war, he went to work for the Rockford Screw Products Corporation, selling screws and bolts to the major automotive companies in the Detroit/Grand Rapids area, a job he held for the rest of his working life. Articulate and distinguished-looking, Pipp was an expert golfer, a popular after-dinner speaker, and a regular attendee at Yankee old-timer games. A resident of Lansing, Michigan, since 1949, Pipp entered a rest home in Grand Rapids in 1963 after suffering several strokes. In poor health for the last 15 months of his life, Pipp died of a heart attack on January 11, 1965. He was survived by his wife, the former Nora Powers, and four children. He was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, in Grand Rapids.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

Ira Smith. Baseball’s Famous First Basemen. New York: A.S. Barnes And Co., 1956.

“Wally Pipp’s Big Headache”, Yankees Magazine, August 1988.

“The Guy Before Gehrig”, Yankees Magazine, January 2002.

“Gehrig, Not Headache Benched Wally Pipp,” by William C. Stryker in a Princeton alumni magazine.

The Sporting News

New York Times

The New York World-Telegram

Wally Pipp’s Hall of Fame file.

Wally Pipp, private letters.

Full Name

Walter Clement Pipp

Born

February 17, 1893 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

January 11, 1965 at Grand Rapids, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.