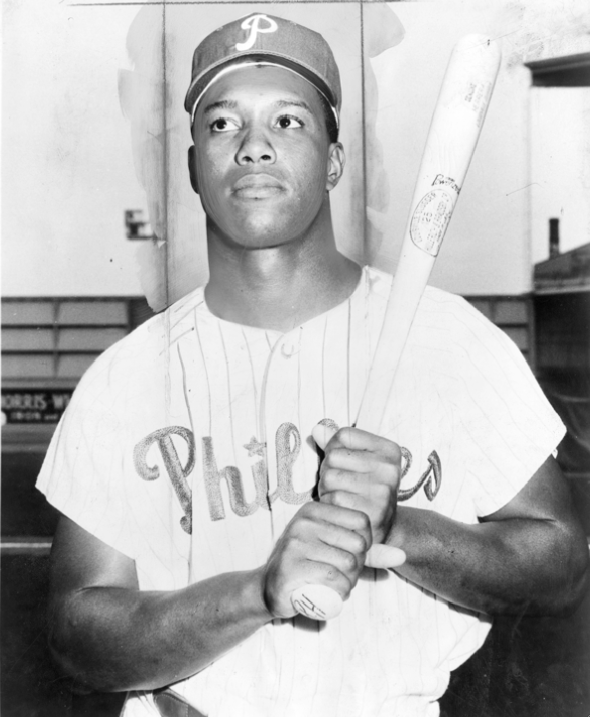

Wes Covington

In the summer of 1952 the Eau Claire Bears, the Boston Braves’ affiliate in the Class C Northern League, featured two young African-American outfielders who would go on to have long careers in the major leagues. One was Hank Aaron; the other was Wes Covington. Aaron went on to become one of baseball’s all-time greats and a member of the Hall of Fame.

In the summer of 1952 the Eau Claire Bears, the Boston Braves’ affiliate in the Class C Northern League, featured two young African-American outfielders who would go on to have long careers in the major leagues. One was Hank Aaron; the other was Wes Covington. Aaron went on to become one of baseball’s all-time greats and a member of the Hall of Fame.

As a young player, Covington was thought to be in Aaron’s class. His skill and potential were so boundless that Aaron, in reference to the Eau Claire team, wrote in his autobiography, “At that point, if people had known that one of our players would someday be the all-time major league home run leader, everybody would have assumed that Covington would be the guy.”1 It was not to be. Covington’s injuries and outspokenness combined to keep his potential from ever being fully unlocked. The Phillies Encyclopedia put Covington’s career succinctly, stating, “Wes Covington lasted 11 years in the major leagues because of a bat that made a lot of noise and in spite of a mouth that did likewise…. (He) specialized in long home runs and long interviews that tended to get people around him a bit testy.”2

John Wesley Covington was born on March 27, 1932, in Laurinburg, North Carolina, a town 100 miles southeast of Charlotte, near the South Carolina border. He grew up in Laurinburg and was a standout athlete in three sports during his high-school days. Baseball was not one of them, however, as the 6-foot-1, 205-pound Covington excelled in football, basketball, and track. After beginning at Laurinburg High, Covington transferred to Hillside High School in Durham, 100 miles away, primarily because of its athletics program. On the gridiron for Hillside, Wes starred as a running back in the same backfield as future Los Angeles Rams back Tom Wilson, and also excelled as the team’s kicker.3 He was named to the all-state team twice as a fullback, and was clocked at 9.9 seconds in the 100 meters.4 A “B” student, Covington had offers to play college football at North Carolina State, UCLA, and several small colleges.5

In the spring of 1950 Covington gained his first baseball experience on local semipro teams. In 1951, with the North Carolina team in need of an outfielder for the annual North Carolina-South Carolina High School Baseball All-Star Game, Covington was asked to play in the game despite the fact that he had never played high-school baseball. Starting in left field for the North Carolina squad, Covington impressed Boston Braves scout Dewey Griggs enough to be offered a contract. After some convincing, he decided to forgo any possible football future and give professional baseball a try. “You know how it is,” he recalled a few years later. “I needed a few dollars, they had a few dollars. Good deal. Besides, my wife, then my sweetheart, asked me to play baseball instead.”6

The Braves sent Covington to Eau Claire in 1952 for his first taste of professional baseball. There he hit .330 with 24 home runs, including four grand slams. Covington spent the season rooming with Aaron and catcher Julie Bowers at the local YMCA. The trio of young blacks were refused rooms at a hotel in Aberdeen, South Dakota; and a promotion at an Eau Claire restaurant offering a free steak to any member of the local nine who hit a home run was abruptly canceled when it was learned that Eau Claire’s three biggest home run hitters – Aaron, Covington, and Bowers, were black.7

During the season Covington was hit in the head by a pitch and spent two weeks in Eau Claire’s Luther Hospital. He recounted his experience in Hank Aaron’s I Had A Hammer:

“I was the first black person who ever went into the hospital there. I felt like a sideshow freak. They assigned different nurses to me every day so they could all get the experience of being in my presence. Actually, I was treated very nicely. The nurses would open my mail and water the flowers for me. All but this one. One nurse, a lady who must’ve been sixty or seventy years old, had the job of putting water in my pitcher every day. This pitcher was on a tray by the door, and I’d look up and see this arm coming around the door and picking up the pitcher. Then the arm would come around and put the pitcher back. I never saw anything more than the arm. Then one day I was out of bed when she came, and I looked at her. She just froze. I said something, and she just stared at me. She poured the water very nervously, then left. I asked somebody about it later, and they said she had never seen a black person before and didn’t know what to expect. Well, one day I was close enough to the door and handed her the pitcher. Then she started to acknowledge me, like bowing her head real fast. Finally, she said something. After that we had a conversation, and by the time I left the hospital, she was sitting at the side of the bed talking to me like an old friend.”8

In 1953 Covington played in 42 games for Evansville of the Class B Three-I League before being drafted into the Army. He played for the teams at Fort Knox, Kentucky, and Fort Lee, Virginia, in 1954. With his service commitment completed, Covington was assigned to Jacksonville in the Class A South Atlantic League in 1955. (Hank Aaron had done the same thing in 1953.) Some hailed Covington as “the next Hank Aaron,” but he professed to take this hype in stride. “You can’t afford to take press clippings seriously,” he said. “You have to make the club on the field, not in the newspapers, and you have to do it on your own. I’m not going to try to be another Aaron or another anybody else.”9

Playing in the Puerto Rican Winter League between the 1955 and 1956 seasons, Covington hit .319 with 12 home runs, led the league in RBIs, and tied Vic Power of the Kansas City Athletics for the lead in hits. Then it was up to the major leagues. Covington made his debut in the Milwaukee Braves’ second game of 1956. Pinch-hitting in a tie game against the Chicago Cubs, he singled home Bill Bruton with what proved to be the winning run for the Braves. The next day in St. Louis, Covington was again summoned to pinch-hit. With the Braves trailing by a run and Bruton on second, he homered to put the Braves ahead. After only two games in the major leagues, Covington had twice come up with big hits to help his team win. For the season he hit .283 with two home runs and 16 RBIs. He also began to draw notice for wasting time at the plate, and for his unorthodox batting stance. Regarding his behavior at the plate, Baseball Digest opined, “In the time it takes for Covington’s ritual of hand dusting, cap adjusting, spike cleaning and deep scowling, the Senate could hold a dozen filibusters.”10 A couple of months later, the magazine described his batting stance as “leaning backward as if in a monsoon, the bat held out straight like a housewife waiting with a mop for hubby to stick his head in the door at 4 a.m.”11

The next two seasons were banner years for Covington and the Braves. Given a chance to win the everyday left-field job in 1957, he faltered in spring training and found himself back in the minors at Triple-A Wichita when the job was given to veteran Bobby Thomson in May. Covington complained loudly that he got the runaround from the organization when he tried to found out why he was not sticking with the big club. Then in June, when the Braves sought to acquire Red Schoendienst from the San Francisco Giants to play second base, general manager John Quinn almost had to send Covington to the Giants to complete the deal. But Quinn gave up Thomson instead, and with no other options in the organization, the Braves were forced to play Covington every day.

Covington responded by hitting .287 with 21 home runs in 90 games after his return from exile. The Braves went 60-30 in the 90 games on the way to their first pennant since 1948. In the World Series, which the Braves won in seven games over the Yankees, Covington played every inning. He hit only .208 with one RBI, but made two crucial defensive plays though he was not normally known as a stellar fielder (he had more errors than assists during his career and once said; “They don’t pay outfielders for what they do with the glove.”)12

In the second inning of Game Two, with Lew Burdette pitching for the Braves and two men on base, Yankees pitcher Bobby Shantz hit a liner down the left-field line that appeared to be an extra-base hit. But Covington chased the ball down, making a backhand catch on the dead run and saved two runs.13 He added a go-ahead RBI in the fourth inning as the Braves won the game, 4-2. Covington’s catch made him so popular in town that he had to temporarily move out of his house because the phone was ringing off the hook. “I couldn’t get any sleep at home,” Covington said. “The phone kept ringing. Why, I bet I’ve got a hundred telegrams so far.”14

Covington again rescued Burdette from trouble in Game Five when he leaped above the wall in left to steal a home run from Gil McDougald. The Braves won the game, 1-0, and eventually won the Series in seven games.15

Covington faced his first major battle with injury in 1958. Playing in a spring training game in Texas, he suffered a knee injury while sliding and was sidelined until May 2. He appeared in only 90 games during the season, but was productive when he did play, hitting .330 with 24 home runs and 74 RBIs as the Braves won the pennant again. Wes started all seven games of the World Series though this time they lost to the Yankees in seven games.

In 1957 and 1958 Covington finish third on the Braves in home runs and RBIs behind Hank Aaron and Eddie Mathews but he played barely more than half the number of games the two future Hall of Famers played in. In fact, in those two seasons Covington hit a home run every 13.8 at-bats, while Aaron, who won the NL home run crown in 1957, hit one out every 16.4 at-bats.16

For Covington, those two seasons were the high-water mark of his major-league career, which had eight more years to go. In 1957 and 1958 he hit more than one-third of his 128 career home runs. In 1959, though he had the most at-bats he of his career, his production declined sharply; his batting average dropped to .279 and his home run total fell to seven, from 24 in 1958. His season ended on August 20 when he tore an ankle ligament. Though manager Charlie Dressen consider him “the key to the Braves pennant hopes,”17 1960 was even worse; Covington reported to spring training “grossly out of shape”18 and still hobbled by the ankle injury. He didn’t start a game until May 4, and was benched as an everyday player in July. He struggled his way through a .249 season.

Covington’s career continued to slide. He held out before the 1961 season, and some sportswriters questioned whether he had stopped applying himself and was now more interested in tending to the cocktail bar and the rooming houses he had purchased.19 During his holdout, Covington threatened not to sign “unless certain things were written into (his) contract.” Braves general manager John McHale sneered, “.200 hitters don’t give ultimatums.”20 Clearly having overestimated his value, Covington ended his holdout on March 8. He started only five games during the first month of the season. The final confirmation of his over-inflating of his value came when he was sold to the Chicago White Sox for the $20,000 waiver price on May 10. Then, after four home runs and 15 RBIs in 22 games for the White Sox, Covington was moved again, this time to the Kansas City Athletics as part of a seven-player deal. Barely three weeks after that, Covington was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies for outfielder Bobby Del Greco, his final stop for the ’61 season and his fourth team in less than ten weeks. The Phillies had been the last team in the National League to integrate (employing its first black player, John Kennedy, only as recently as 1957), and Covington was the first African-American to realize a significant role with the team.21

Covington found a more permanent home in Philadelphia, and ended up playing more games for them than for any other team. Still, his career with the Phillies was just as volatile as his time with the Braves. He often found himself at odds with manager Gene Mauch. The main source of discord seemed to be Covington’s unhappiness with Mauch’s platoon system, in which the left-handed hitting Covington rarely played against left-handed pitching. The statistics, however, bear out Mauch’s position; Covington hit only .205 against left-handed pitchers from 1962 through 1965. Also, his defense had been made even more suspect by the injuries to his legs, and he was routinely removed in late innings for defensive purposes.

Despite his limitations, Covington was a productive player during his 4½ with the Phillies. He appeared in more than 100 games each of his four full years with the team, the only time during his career when he was healthy enough to do so. His average season was .281 with 14 home runs and 53 RBIs, and in 1963 he hit .303 with 17 home runs and 64 RBIs. Being used in a platoon also gave Covington numerous opportunities to pinch-hit, and he excelled in the role, notching 33 pinch hits as a Phillie. But the defining moment of Covington’s stay in Philadelphia was the collapse of 1964.

For the first 5½ months of the 1964 season, everything went the Phillies’ way. Sitting atop the National League standings by 6½ games with only 12 left to play, they seemed like a lock to reach their first World Series since 1950. When World Series tickets went on sale, many of the players, with the team in Houston, went shopping with their anticipated bonus money. Covington bought a rifle and brandished it in the clubhouse, saying “This is for the sportswriters.”22 However, as all baseball historians and Philadelphians know, that bonus money never came, as the Phillies went on a ten-game losing streak that turned their huge pennant lead into a second-place tie.

After the stunning end to the 1964 season, Covington spent the offseason pointing the finger for the collapse in every direction except his own, and then showed up for 1965 spring training 15 days late.23 The Philadelphia Daily News wrote, “(Covington) kept hollering and kept popping up. … Nobody wants to listen to a mean, tough grumbler when that grumbler is hitting .220. The Phillies lost the pennant, and Covington went around town all winter telling people whose fault it was, and never even mentioned Wes Covington’s name.”24 (Covington was being platooned during the disastrous ten-game losing streak and had hit .150 with no home runs, RBIs, or runs scored.)

Covington lasted one more contentious season with the Phillies. At the end of the 1965 season he asked to be released. In early January 1966 he was traded to the Chicago Cubs for Doug Clemens, and Cubs manager Leo Durocher announced his intention to play Covington every day, even against left-handed pitching.25 Despite Durocher’s pronouncements, Covington’s Cubs career lasted only nine games before he was released in early May. Shown interest from contenders in both leagues, he signed with the Los Angeles Dodgers, thinking this was his best chance to win. Covington was largely used as a pinch-hitter for the Dodgers, and finally proved to be the veteran leader who was sorely missed during his time in Philadelphia. He was such a vocal supporter from the dugout that at one point Dodgers manager Walter Alston had to explain to an umpire that Covington was only trying to provide his teammates a “loud lift.” But his support wasn’t just intangible, as he reached base 10 times in 14 plate appearances during one stretch late in the season.26 The Dodgers won the pennant but were swept by the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series. Covington made one appearance, striking out as a pinch hitter in Game One. It was his last appearance in the major leagues.

The man who once had said his hobbies were “hitting homers and making money” had handled his money well as a player, and had numerous business operations outside of baseball as he transitioned into post-baseball life. He owned a barbecue restaurant in Philadelphia, held real estate in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Florida, and had a business, Diamond Janitorial Services, that grew into one of Philadelphia’s largest janitorial service companies.27 However, at some point in the late 1970s, tax issues had forced Covington and his wife to Canada.28 They settled in Edmonton, Alberta, where he operated a sporting-goods store and then spent nearly 20 years working in advertising for the Edmonton Sun.29 Covington also became involved with the Triple-A Edmonton Trappers. In 2003 he returned to Milwaukee for the first time in 40 years at the invitation of the Braves Historical Society, and in 2007 he was one of 14 members of the 1957 champs to gather in Milwaukee to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Braves’ world championship.30 Covington died of cancer on July 4, 2011, in Edmonton.

This biography is included in the book “The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2013), edited by Mel Marmer and Bill Nowlin. It is also included in “Thar’s Joy in Braveland! The 1957 Milwaukee Braves” (SABR, 2014), edited by Gregory H. Wolf.

Sources

Aaron, Hank, with Wheeler, Lonnie. I Had a Hammer: The Hank Aaron Story (New York: HarperCollins, 1991)

Buege, Bob. Milwaukee Braves: A Baseball Eulogy (Milwaukee: Douglas American Sports Publications, 1988)

Caruso, Gary. The Braves Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995)

Kashatus, William. September Swoon (University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Stat University Press, 2005)

Moffi, Larry, and Kronstadt, Jonathan. Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers, 1947-1959. (Lincoln: Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press, 2006)

Poling, Jerry. A Summer Up North (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2002)

Povletich, William. Milwaukee Braves: Heroes and Heartbreak (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2009)

Westcott, Rich, and Bilovsky, Frank. The Phillies Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003)

The author also consulted Wes Covington’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Baseball-Reference.com, and various issues of Baseball Digest, the Milwaukee Journal, the Philadelphia Daily News, Sport, Sports Illustrated, and The Sporting News.

Special thanks to my wife, Carrie, a librarian, for tracking down a seemingly endless list of obscure books I requested as I attempted to learn about Wes Covington’s life and career.

Notes

1 Hank Aaron, with Lonnie Wheeler, I Had a Hammer: The Hank Aaron Story (New York: HarperCollins, 1991).

2 Rich Westcott and Frank Bilovsky, The Phillies Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition.

3 Wes Covington player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

4 Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt, Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers, 1947-1959.

5 Milwaukee Journal, September 8, 1957.

6 Wes Covington player file.

7 Jerry Poling, A Summer Up North.

8 Aaron, op. cit.

9 Moffi and Kronstadt, op. cit.

10 Baseball Digest, June 1963.

11 Baseball Digest, August 1963.

12 Moffi and Kronstadt, op. cit.

13 Bob Buege, Milwaukee Braves: A Baseball Eulogy.

14 Wes Covington player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

15 Moffi and Kronstadt, op. cit.

16 Gary Caruso, The Braves Encyclopedia.

17 The Sporting News, August 31, 1960,

18 Bob Buege, op. cit.

19 Milwaukee Journal, May 12, 1961.

20 The Sporting News, February 1, 1961.

21 William Kashatus, September Swoon.

22 Ibid.

23 Wes Covington player file.

24 Philadelphia Daily News, March 29, 1965.

25 Wes Covington player file.

26 The Sporting News, October 1, 1966.

27 Sports Illustrated, July 22, 1968.

28 Wes Covington player file.

29 Baseballsavvy.com article accessed at: http://www.baseballsavvy.com/archive/w_wesCovington.html

30 William Povletich, Milwaukee Braves: Heroes and Heartbreak.

Full Name

John Wesley Covington

Born

March 27, 1932 at Laurinburg, NC (USA)

Died

July 4, 2011 at Edmonton, AB (CAN)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.