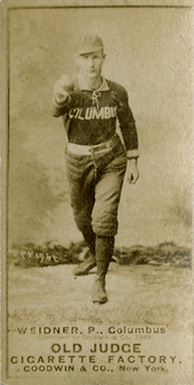

Wild Bill Widner

When a reader sees the nickname “Wild Bill” associated with a pitcher, the first thought is that the fellow suffered with awful control. For example, Wild Bill Donovan debuted in 1898 and walked 69 in only 88 innings. Wild Bill Hallahan led his league in walks every season he pitched over 200 innings. In more recent years fans have marveled at players dubbed “Wild Thing,” like the fictional Ricky Vaughn or the real-life Mitch Williams. That is not how tempestuous Bill Widner earned his nickname. In Widner’s only full season in the majors, 1889 with the American Association’s Columbus Solons, he posted the best walks-per-inning ratio on the club.1 His first manager, Gus Schmelz, said, “Bill had an arm on him like an army mule, his control was perfect.”2

When a reader sees the nickname “Wild Bill” associated with a pitcher, the first thought is that the fellow suffered with awful control. For example, Wild Bill Donovan debuted in 1898 and walked 69 in only 88 innings. Wild Bill Hallahan led his league in walks every season he pitched over 200 innings. In more recent years fans have marveled at players dubbed “Wild Thing,” like the fictional Ricky Vaughn or the real-life Mitch Williams. That is not how tempestuous Bill Widner earned his nickname. In Widner’s only full season in the majors, 1889 with the American Association’s Columbus Solons, he posted the best walks-per-inning ratio on the club.1 His first manager, Gus Schmelz, said, “Bill had an arm on him like an army mule, his control was perfect.”2

William Waterfield Widner Jr.’s volatile behavior off the diamond won him the “Wild” label. (Temper was also a factor for Bill Donovan.) Indeed, Widner grew up in a place with a reputation for rowdyism — the small town of Cumminsville, Ohio, which lay on the northern edge of Cincinnati. “Dubbed ‘Helltown’ by Cincinnatians, it was known for its barrel houses and honky-tonks, where brawls, feuds, rioting and drunken revelry defied the small village police force,” said a 1940s guidebook.3

Growing up in that environment would explain why Widner had a predilection for the party life. Over the years, writers described him as “carried away by the excitement of a traveling life.” Upon his enlistment for the Spanish-American War it was noted that “he has always remained untamed.”4 Game stories reveal a man who could bedazzle you with talent one moment before turning surly and going on a binge. In today’s world the term bipolar might be offered as an explanation for his behavior.

Widner was one of six children born to William W. and Francis “Fannie” (Ferguson) Widner. William was of German descent and Fannie came from an Irish family. When Widner was born on June 3, 1867, his father worked for a railroad, probably the Ohio and Mississippi, which ran from Cincinnati to East St. Louis. In later years he took work as a janitor. Widner was educated in a local elementary school before joining the work force.

Cincinnati was a baseball hotbed as Widner grew up. His town of Cumminsville (which was incorporated into the Queen City while Widner was of school age) had four citizens playing in the major leagues in 1887: Widner, Billy Crowell, Bobby Gilks, and George Pechiney. They were all primarily pitchers that season.5 Wild Bill grew to be 6 feet tall and in his prime he weighed in at 180 pounds. When he was initially signed by the Cincinnati Red Stockings in 1887, he was more likely only 165 pounds. He was a right-handed thrower and batter.

Widner worked his way up through the amateur and semipro ranks before signing with the local American Association team while still a teenager on May 28, 1887. He accompanied the team on its Eastern swing the first half of June. He saw his only action on June 8 when manager Schmelz gave him the starting assignment in the second game of a doubleheader in Philadelphia.

The sixth-place Red Stockings staked Widner to a lead early, but the Athletics came back and after a home run by Cincinnati native Denny Lyons they led 8-6 going into the Cincinnati half of the ninth. Cincy rallied and tied the game with a single, walk, and double. This brought Widner to the dish. He laced a single to drive in the winning run. He remained with the team until late July, seeing action in exhibitions, but had no more regular-season action. He joined the Cincinnati Shamrocks, the finest local semipro squad, in late July. The Red Stockings officially released Widner in August when management told Schmelz he had too many pitchers.

The New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern League were stocked with talent from Cincinnati. Most notable on this list were pitcher John Ewing, catcher Farmer Vaughn, and shortstop Shorty Fuller. No doubt these players alerted the Pelicans to Widner’s availability and talent. He joined the team when its was on a road trip to Nashville and Memphis.

Widner saw his first action when the Pelicans returned home. He was matched against 25-game winner Al Hungler of the Charleston Quakers. Widner “showed coolness, judgment and better command of the ball than any pitcher … this season,” wrote an observer.6 The Quakers rallied in the ninth to win 3-2 before 3,000 fans. Widner had a rematch with Hungler later in the series and this time he emerged with a 4-1 victory.

The Southern League had shrunk to a four-team circuit when Widner arrived. He posted a 10-5 record for the Pelicans. He also performed well with the bat. In a three-game stretch against Memphis and Birmingham, he smacked 10 hits, half his season total. New Orleans ran away from the league with a 78-37 record. The Pelicans closed out their season hosting the New York Giants in an exhibition series.

In that series Widner twice found himself matched against Tim Keefe. The first encounter ended in a 4-4 tie. The scribes gave Widner credit for his “remarkably deceptive pitching, his excellent command of the ball and his splendid judgment.”7 In the second meeting the Pelicans jumped out to a 4-0 lead, but Widner could not hold the Giants down and lost, 5-4.

Widner returned to Cincinnati but was back in New Orleans by mid-February for the exhibition season. His first action came in a 3-1 loss to Cincinnati. Widner had signed early, which would indicate he received the $275 a month he was seeking.8 He became the workhorse of the pitching staff, but with most of the Cincinnati contingent no longer with the team, the Pelicans struggled in the box and at the plate.

Widner found himself in trouble with the law when he got into a barroom brawl on Royal Street in the French Quarter. He used a beer mug to smash the head of a patron and was arrested. But the bar fight was not Widner’s only wild exploit. In late June a spat arose in a game with Birmingham when the allotted supply of baseballs ran out. A lengthy argument ensued about using new baseballs and who would supply them.

League President J.T. Wilson was on hand and he and umpire Tony Suck finally resolved the matter. Widner was sent back to the box but lost his temper. He tossed several balls “over the grand stand” while his teammates did everything possible to slow down the game and hope for darkness. The Times-Picayune summed it up: “The game henceforth was an unpardonable burlesque beggaring description.” The league handed out fines totaling nearly $500 on New Orleans players.9

The Southern League began to unravel and “ceased to exist” on July 10.10 Ted Sullivan, manager of the Washington Nationals, went south looking to get talent for his team. He managed to secure Fuller, Widner, and Perry Werden from the New Orleans roster. They played their last game with New Orleans on July 13 after a merger of the Southern and Texas Leagues. Widner played center field in the contest.11 A month later the New Orleans franchise disbanded after the merger of the Texas and Southern Leagues also failed.

The New Orleans management sought an injunction to prevent Widner and Werden from playing with Washington. (Oddly, they did not do the same for Fuller.) As the court case dragged on, Widner played for the Nationals. One of his finer career efforts came on September 1 against Philadelphia, when he spun a 12-inning four-hitter but lost 2-0. The legal wrangling over Widner continued into mid-October when a 55-day extension was granted, essentially making the issue moot.

The Nationals were less than enthralled with Widner. They released him and outfielder Ed Daily in early 1889. Both players were quickly signed by the Columbus Solons in the American Association. Solons manager Al Buckenberger entered the season with an ailing lineup, especially his star hitter, Dave Orr. The Solons opened the campaign with a 13-3 win over Baltimore but that was one of their few highlights. The pitching staff surrendered 62 runs in the next four games and the team settled into the second division. Widner was one of three players who were fined for a drinking binge just after the team arrived in Baltimore. Wild Bill found himself $100 lighter.

Buckenberger may have had plans for a pitching rotation; if so, he scrubbed them and went with Mark Baldwin as often as possible. One week in June when there were offdays and a rainout, Baldwin tossed three complete games and no other pitcher saw action. Widner was used in relief and as a spot starter until late July, when his performances finally caught Buckenberger’s fancy. Widner and Baldwin split most of the work in August and early September.

After three straight wins, Widner dropped a contest to Kansas City on September 8. Soon after, he was suspended so he could “cut the acquaintance of John Barleycorn with whom he has been on too intimate terms.”12 The suspension lasted the remainder of the season. In December Widner signed with Columbus for the 1890 season.

Widner reported in good condition and was penciled into a rotation with Hank Gastright and Jack Easton. There was even a plan in place to have each pitcher work with a personal catcher. A broken thumb shelved Widner until May 10, when he earned the win over Louisville. He took five losses before entering the win column again. The Solons parted company with Widner during the second week of July.

The Sioux City Corn Huskers in the Western Association had a contingent of Cincinnati natives on their roster. Widner found his way there and made his first start on July 22. He played 30 games for Sioux City, 27 of them as a pitcher. He made only six errors and was considered the best fielding hurler in the circuit. At the plate he hit.258. He posted a 14-11 record with a 2.48 ERA for the fifth-place Corn Huskers.13

Widner’s performance made him a fan favorite in Sioux City, but the rest of the league was less hospitable. He had a habit of working very slowly. Writer Sandy Griswold of the Omaha Bee called him “the most aggravating and tiresome pitcher in the Western Association,” and added, “This makes a batter furious, and that’s what wily Wild Bill is engineering for.”14

The Corn Huskers expected Widner to return in 1891 but contract negotiations dragged. In late April, instead of being in Iowa, Widner was playing with the Shamrocks again. In early May he finally came to terms with Sioux City but then took his time traveling west. He made his first appearance on May 14 and took a pounding from Lincoln in a 13-8 loss.

Widner relieved on May 17 and poured gasoline on a rally to create an eight-run sixth inning for Lincoln. Two days later he barely escaped death from asphyxiation when he and his roommate fell asleep with the gas on in their room.

Widner was given a start again on May 30 against Minneapolis and surrendered seven home runs in a 19-3 complete-game loss. Three days later he lost to Milwaukee by “only” a 5-0 score. The Huskers had seen enough and released him. He returned to the semipro game in Cincinnati.

King Kelly’s Killers were mired in the second division of the American Association. To excite their fans, they signed Widner and local infielder Joe Burke on the morning of July 23. That afternoon both men were in the lineup against St. Louis. Both got a hit and fielded flawlessly. Widner was wilder than usual, walking two and hitting Charlie Comiskey and Tip O’Neill on his way to a 7-4 defeat. It proved to be the only appearance for both Widner and Burke with the Killers.

In early November Jack Boyle and Fuller organized a group of Cincinnati area players to go to New Orleans. Widner and Bobby Gilks were the pitchers on the team. When he returned to the Queen City, Widner took Hattie Duvall as his wife. She was described as “one of the prettiest girls in Camp Washington.”15 The couple were united in Christmas Eve nuptials.

Widner’s relationship with Hattie was stormy. She sued for divorce in the fall of 1895, claiming he would not work or support her. “He often beat and threatened to kill her,” wrote the Cincinnati Enquirer.16 The divorce was granted but the couple remarried quickly, on January 4, 1896. They separated after a year and another divorce followed. The police were called for domestic disputes during the separation and Widner was arrested for beating Hattie (who worked as a stenographer to support herself).

Widner joined the Milwaukee Brewers in the Western League in 1892. He was only 25, but this would prove to be his final season in professional baseball. Columbus and Milwaukee were the class of the Western league. Columbus was about 30 percentage points ahead of Milwaukee when the league folded on July 11. Widner posted a 10-7 record.

Reportedly the Brewers had $18 in their treasury when the league folded. One sportswriter quipped that Widner’s final payday consisted of “three baseballs and a catchers liver pad.”17In 1894 Widner filed suit against the new Brewers franchise demanding payment of the $123.35 he claimed to be owed.18 How the case was resolved is unknown.

When the Brewers folded, Widner joined the Mobile Blackbirds in the Class B Southern League. He could not fool the league hitters and surrendered 15 runs in 16 innings while absorbing three losses. He returned to the semipro game in Ohio. In 1893 the pitching distance was set at 60 feet 6 inches and the mound and rubber were introduced. Widner never played professionally again. It is uncertain whether his poor habits or the greater distance were the primary factor.

Widner would be active in the Cincinnati baseball scene for the next five years. He managed the Cumminsville Arctics beginning in 1893. He also played with teams like the Mohawks and the Norwood Eagles. He pitched less and less often, possibly indicating that his arm was weakening. In 1895 he had a brief fling with a boxing career.

When the Spanish-American War broke out, Widner enlisted in the 2nd Regiment of the volunteer engineers, known as Huston’s Engineers. He rose to the rank of corporal with the unit. Discharged in June 1899, he found work with various engineering firms, served as a fireman, and was a city inspector during the next decade. He even tried his hand at politics by running for the local council in the Cumminsville area.

Widner’s health began to fail, and he made a trip to Hot Springs, Arkansas, in 1905 hoping for a cure or relief. He was bedridden in the fall of 1908 and died in his home on December 10, 1908, from complications of diabetes. He was buried in Wesleyan Cemetery in Cincinnati.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and verified for accuracy by the BioProject fact-checking team. Team records are courtesy of the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball.

Notes

1 Mark Baldwin led the staff with over 500 innings pitched — but led the league in walks and averaged 4.8 walks per nine innings. Hank Gastright came in at 4.2, Al Mays at 3.6, and Widner at 2.6. Widner’s 12 wild pitches were the lowest for any league pitcher with 240 or more innings.

2 “Discovery of ‘Wild Bill,’” Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln), April 17, 1892: 15.

3 Cincinnati: A Guide to the Queen City and Its Neighbors, compiled by the Writers Program of the WPA (Cincinnati: Weisen-Hart Press, 1943), 31.

4 Joe and Jack Heffron, The Local Boys, (Birmingham, Alabama: Clerisy Press, 2014), 214-15.

5 Bill Lamb, “George Pechiney,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproj/person/ced73a27. Most recently accessed March 6, 2019.

6 “A Tough Tussle,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), August 28, 1887: 12.

7 “A Tie,” Times-Picayune, November 1, 1887: 3.

8 “The New Orleans Team,” Times-Picayune, October 21, 1887: 3. The article noted that the team’s salary was $14,000 in 1887 and that the players’ demands for the following year could push it to $30,000.

9 “Wrecker Goldsby,” Times-Picayune, June 28, 1888: 2.

10 “Sporting Events,” Times-Picayune, July 10. 1888: 2.

11 “A Drawn Battle,” Times-Picayune, July 14, 1888: 2.

12 “Wild Bill Takes a Vacation,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 17, 1889: 2.

13 “The Western,” Sporting Life, October 25, 1890: 8. The 1891 Spalding Baseball Guide is the source for the won-lost record.

14 “Sandy Griswold on Bill Widner,” Sioux City (Iowa) Journal, August 25, 1890: 3.

15 Heffron.

16 “Beaten and Deserted,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 17, 1895: 12.

17 Boston Globe, July 16, 1892: 5.

18 “All Sorts,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 8, 1894: 10.

Full Name

William Waterfield Widner

Born

June 3, 1867 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

December 10, 1908 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.