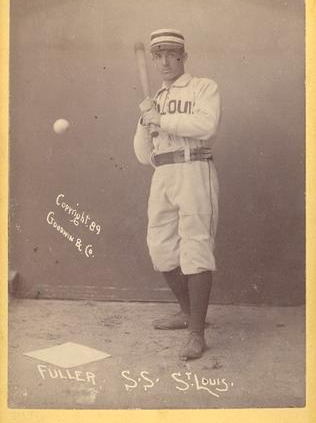

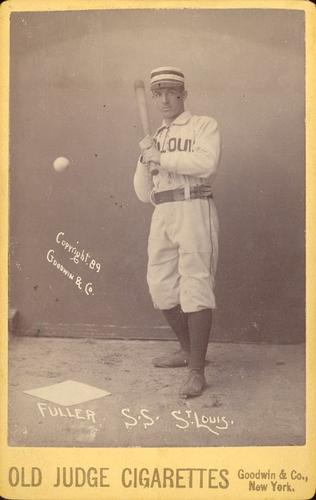

Shorty Fuller

The light-hitting, 5-foot-6 shortstop William Benjamin Fuller parlayed his excellent fielding into a nine-year career in the majors (1888-1896), beginning with a 49-game stint with the National League’s Washington Nationals. In 1889 he began a seven-year stretch as a starting shortstop, first with the American Association’s St. Louis Browns and then later back in the NL with the New York Giants. He set the major-league record for putouts in a game at shortstop with 11 on August 20, 1895, a record he still co-holds.1

The light-hitting, 5-foot-6 shortstop William Benjamin Fuller parlayed his excellent fielding into a nine-year career in the majors (1888-1896), beginning with a 49-game stint with the National League’s Washington Nationals. In 1889 he began a seven-year stretch as a starting shortstop, first with the American Association’s St. Louis Browns and then later back in the NL with the New York Giants. He set the major-league record for putouts in a game at shortstop with 11 on August 20, 1895, a record he still co-holds.1

Fuller co-holds another major-league record, which he set his rookie year by committing four errors at shortstop in a single inning, that being in the second inning of the Senators loss to the Indianapolis Hoosiers on August 17, 1888.2 In his defense (pun intended), “good fielding was impossible” as the field had been inundated by a deluge just before the second inning began.3 “Then Came the Waterloo,” as the (Washington, D.C.) Evening Star described it.4

Fuller got his nickname early in his minor league career, but ultimately it referred to more than just his stature. According to Browns owner Chis Von der Ahe, Fuller’s nickname also related to his ability to make “short work” of any ball hit to shortstop.5

While only a career .235 hitter, Fuller’s outstanding ability as a fielder earned him the adulation of fans in both St. Louis and New York. Despite his low batting average Fuller brought something intangible to the plate (including a more respectable career OBP of .322), the ability (and willingness) to advance runners via the sacrifice bunt, and speed on the basepaths (with 260 career steals).

While baseball fame can be fleeting, the popular shortstop’s fielding made an impression that was not so quickly forgotten. As late as the mid-1930s, articles mention him as one of the top shortstops in Giants history.6 He was also hailed as a distinguished shortstop for the Browns more than 30 years after he left that team.7 Fuller earned these accolades despite playing only four full seasons with the Giants and three in St. Louis.

William Benjamin (Bernard) Foeller was born on October 10, 1865, in Cincinnati, Ohio, to Louis (Ludwig) and Kate (Catherine) Foeller. Both parents were born in Prussia and were living in Ohio at least by 1857 according to information in the 1870 census. Louis worked as a plasterer and Fuller learned the trade from him. Kate maintained the household. Fuller generally referred to himself as Ben.

The exact year of Fuller’s birth is not entirely certain as different sources reflect a year of birth between 1865 and 1867. However, census information provided by his parents in 1870 and 1880, and his death certificate and Cincinnati obituary, which both list him as age 38 in 1904, are all consistent with a birth year of 1865.8

At the time of the 1870 census, he had older siblings Annie and Henry (also known as Harry), and a younger sibling Frank. Sisters Mary (born 1870) and Lizzie (born 1873) later joined the family, but mother Kate died in 1873 at age 41 (from complications in giving birth to Lizzie).9 Brother Frank died in 1875. About that time Louis married a women named Anna, and half-sisters Rose and Catherine (Katie) were included in the family in the 1880 census.

Cincinnati directories list the family as Foeller until 1890 when the switch is made to Fuller. The directories list Fuller himself under two listings, one as Benj. (occupation ballplayer) and another as Wm. B. Fuller (occupation plasterer) at the same address.

Fuller gained notice as playing for amateur teams in the Mill Creek/West End bottoms area of Cincinnati10 before becoming a member of the Henley Club of Richmond, Indiana, in 1885, where he usually played third base.11 The following season both Ben and brother Harry Fuller, also a future major leaguer, were playing for the Cincinnati Clippers, a team viewed as one of the top amateur teams in Ohio.12 Fuller may have also played with the Blue Licks team in 1885 and 1886, arguably the top team in the city, which was actively recruiting players from the Clippers at the time.13 Toward the end of that season the brothers were both playing for the Nicholasville team, the Kentucky state amateur champions, and batting first and second. Ben played shortstop.14

The baseball fortunes of the brothers changed with their joining of the New Orleans Pelicans team in Southern League in December 1886. Shortly after he joined the team Ben became known as “Shorty.”15

As it would his entire career, Fuller’s fielding quickly earned the admiration of the fans. The press noted that his fielding prowess often allowed him to cover up the miscues of others.16 In games where he did commit an error, the Times-Picayune commented that his other plays more than made up for them.17

Perhaps as good a description of what Fuller could do in the field (with the minimalist glove of the 1880s) comes from an article in the New Orleans Times-Democrat of August 1, 1887. Shorty Fuller:

“performed feats never excelled by any of the big professionals in any league. He began his work in the second inning, when Firle gave him a hot one along the ground, which he gathered up, cutting the runner easily. His style of throwing is that of a quick snap, that fires the ball like a bullet from a Springfield. In the third, he cut off Hogan at first. His next came like a hot shot through the air from Hayes’ bat. As it flew over his head he jumped into the air after it, clutching it with his right [bare] hand while the crowd applauded. In the fourth, he captured a fly of Firle’s after a long run over to the foul line. In the fifth, he took a burner on a straight line from Hayes’ bat. In the sixth, he darted away in the rear of third base, scooping in a fly of Hogan’s. In the seventh, he cut Clinton off on a daisy cutter. In the ninth he headed off at first both Hogan and Hayes. His record for the day was brilliant, stamping him as a short stop par excellence.”18

Fuller wasn’t just a glove. He finished the year in New Orleans with a batting average of .325 and 65 steals. Although the 157-pound right-handed hitter and thrower was not hitting with much power, he gradually moved up to fifth in the lineup.

After the season New Orleans fans and his teammates anxiously watched what the popular player would choose to do and were quite relieved when he re-signed with the New Orleans club.19 Harry’s career took him in a different direction. He left the New Orleans team mid-season and went to a variety of minor league teams over the next few years. He and Shorty met up for brief appearances together for the St. Louis Browns in 1890 and 1891.

With the start of the 1888 season, Shorty Fuller found himself leading off for the Pelicans in a Southern League that was in financial trouble. Although he continued to earn accolades for his fielding, Fuller missed games due to illness and a sprained ankle.20 His batting average fell to .252. But that did not deter Washington Nationals manager Ted Sullivan, the peripatetic baseball entrepreneur, manager, scout, sometime (but typically erratic) umpire, and founder of the Southern League (in 1886), from trying to acquire Fuller for the Washington team in July as the Southern League gradually collapsed.

Other teams were interested in Fuller as well, including Louisville, Kansas City, Cleveland, and Detroit. Sullivan got ahead of the competition by offering New Orleans $1,000 for Fuller, which the Pelicans accepted.21 Fuller expressed a preference for going to a team in the American Association to be close to his family, as the Cincinnati ballclub played in the AA. However, with an offer of $1,000 for Fuller in hand, Pelican president Toby Hart convinced the ballplayer that Washington was best for him.22

With other offers for Fuller pouring in, Sullivan realized he needed to make a bold move. If the Southern League collapsed, New Orleans could lose its rights to Fuller, who could then sign with any club he desired. To cover his bases, Sullivan first negotiated directly with Fuller, who agreed to play for Washington at a salary of $350 per month.23 Sullivan then honored his agreement to pay $1,000 to New Orleans, stating that he felt “honor bound to deal squarely with New Orleans.”24 Ultimately, Sullivan also got Wild Bill Widner and Perry Werden from the Pelicans.25

The Philadelphia Times reports that Sullivan signed the deal, paid the fee, and with “considerable diplomacy” coaxed the three players into a sleeping car and spirited them away from New Orleans before other teams could make their moves. Sullivan was widely congratulated on the playing of his “sharp game” to get Fuller.26 About that time the Southern League folded and the New Orleans team joined the short-lived Texas Southern League.

The press in Washington was quite excited about obtaining Fuller, commenting that “Fuller was undoubtedly the star player of the Southern League. His … activity on the field is marvelous, … going after everything there is the slightest chance of getting. … A Washington enthusiast who has witnessed several games in New Orleans says, ‘He is active as a cat and never shirks anything, while his throwing is even better than Will White’s.’”27

Fuller got into 49 games with the Senators after joining the team. He missed time due to illness,28 and after taking a pitch to the head,29 and was benched early on for not producing at the plate.30 He finished the year batting only .182. As would be the case for his entire career, the press frequently commented on his excellent play at shortstop.31

Following the season, Washington sold Fuller to the St. Louis Browns for $800.32 The press in St. Louis and elsewhere questioned the wisdom of the Browns in signing Fuller. In December 1888, shortly after Fuller became a Brown, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat noted that, “The shortstop sold by Washington to St. Louis, is a good fielder but a rather light hitter. Besides, he gets rattled at times and has been known to pile up seven misplays in succession.”33

That opinion was not shared by team ownership. Three weeks later the St. Louis Post-Dispatch published the viewpoint of Browns owner and president Von der Ahe, “I see there is an evident effort to create a prejudice against Short-stop Fuller in advance of his appearance here … The Philadelphia Press gives it out that Fuller must be no good because he ran the gauntlet of different [National] league clubs, who allowed him to come to St. Louis. And then we see the comment that because Washington is said to want Bill] White [the Browns’ shortstop], that necessarily Fuller is White’s inferior. I don’t take any stock in this kind of argument because there is nothing to it. … There is a good deal more in Fuller than people who know him as a ballplayer want to concede. While he was with the New Orleans club he did remarkable work, covering short in a manner which elicited the commendation of Fred Pfeffer, Biddy McPhee, Ed Willamson, William “Yank”] Robinson, Charlie] Comiskey and others who have played against him.”34

Von der Ahe continued, “He is known as ‘Shorty’ Fuller because he usually does his work neatly, with alacrity and dispatch; in fact, makes short work of the duties outlined in his territory. Comiskey wanted me to sign him two years ago. I think he will prove a good man for the Browns.” The boss president concluded the interview by stating that “We hope to win the championship the coming season with Fuller at shortstop.”35

Fuller was offered $1,900 to play for the Browns, and when he initially refused to sign, Von der Ahe pointed out to him that he’d likely only get $1,500 if he returned to the National League under the pay scale then used by that league.36 That appears to have sealed the deal.

Fuller, usually batting seventh, hit only .226 for the year. He stole 38 bases and drove in 51 runs. The press, however, spared no accolades for his fielding. By May he was touted as having no superior at shortstop,37 an opinion reiterated later in the year38 as his fielding was variously described as phenomenal39 and brilliant.40

Nine years later, in 1898, a reporter for the Buffalo Enquirer recalled a play Fuller made that year. The author related that, “When the St. Louis Browns were in the zenith of their glory, I remember a great play that Shorty Fuller accomplished. … The batsman drove out a grounder that was largely hit. Fuller knocked the ball down, fell flat himself, and as the ball rolled away gave it a kick and it fell into [Yank] Robinson’s hands, completing the most sensational force-out I ever saw made.”41

Frank Bancroft, who had 375 wins as a manager over his career, commented in the same month to the Buffalo Enquirer about how hard it was to score on the Browns infield, and not just because of their glove work. “That old St. Louis infield was a hard one to get around. A baserunner would feel safer with an accident insurance policy before he commenced his trip. Going to first Commy [Charlie Comiskey] would likely toss him into the air. Robinson was a king in blocking a man at second, while Lath [Arlie Latham] would always manage to be in the way at third if the pilgrim escaped falling over Shorty Fuller. Any runner who got past that squad would be received at home plate by Doc Bushong and congratulated on getting around alive.”42 A few years earlier, in 1896, the same paper noted that Fuller was not above physically holding players on base when the umpire was not looking.43

Following the 1889 season, the Browns signed brother Harry, with the idea that Harry could play second base.44 The two brothers played side-by-side in several preseason games,45 but Harry was released before the regular season began.46 Harry would return to the Browns for a curtain call in September of 1891.

The 1890 season saw Fuller’s batting average rise to .278 with 60 steals, both career highs. Fuller’s adjusted OPS+ was also a career-high 97. His statistics were likely influenced by the exodus of many of the better players in the AA to the newly formed Players League for its single season. Fuller spent most of the year batting first or second for the Browns. Praise for Fuller’s fielding continued as in prior years, the press calling his fielding acrobatic,47 phenomenal,48 and superb.49 It was noted that his “errors may look bad on paper, but they seldom look bad on the ball field. He takes desperate chances and, in that way, earns the demerit marks.”50

While Fuller was well known for being quiet and a tough interview because of his lack of loquaciousness,51 he could be a feisty fellow as exemplified by a row he instigated with teammate and second baseman Pete Sweeney over what appears to be a minor issue. The altercation eventually required the interjection of owner Von der Ahe and two nearby policemen to calm the situation.52

The Players League folded following the 1890 season, and many of the Browns lost to the PL returned for the 1891 season. Fuller batted second most of the year, but his batting average dropped to .212 and his OBP to .298. He did manage 42 steals, and his fielding continued to get rave reviews with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch noting that, “Shorty Fuller is covering himself and short with glory this year,”53 and that, “Shorty Fuller is playing better ball than he ever did.” 54

Late in the year the Browns re-signed brother Harry. The two appeared on the field together in Harry’s only major league game, on September 19, 1891. With Harry at third base, the brothers contributed two errors each in the Browns 7-4 loss to Washington.55

The 1891 season was Fuller’s last with the Browns. After the season the AA folded and the National League expanded to 12 teams, with the Browns joining the NL. Originally it was thought that the Browns would re-sign many of their players. But Von der Ahe was not inclined to give any of his players a raise.56 As it turned out none of the Browns’ starting eight remained with the team. The result was the Browns (who would later become the Cardinals) finished eleventh in the league. The team would remain a denizen of the bottom half of the NL for all but two of its first 22 years in the senior circuit.

Fuller was reportedly paid $3,500 for the 1892 season by the Giants.57 Player salaries peaked that year, driven up by the mad scramble for the better AA players that resulted from the demise of that league and the contraction of major league teams from 16 in two leagues to 12 teams in just the NL.

Fuller quickly established himself as a fan favorite in New York,58 and he continued to cover himself with glory (and mud at times) in the field.59 In one contest, the New York Times noted that, “the amount of territory he took care of was something remarkable, he made stops and throws that electrified on-lookers.”60 Fuller’s play in the field was often cited as the difference between victory and defeat, or at least resulted in keeping games close.61

In Fuller’s first two years as the Giants’ starting shortstop he hit .228 and .236, and he typically batted near the bottom of the lineup. He was fourth on the team with 37 steals in 1892.

His lack of hitting appears to have convinced Giants manager John Montgomery Ward to try a change at shortstop. In a move belying the Giants’ name, he replaced the diminutive Fuller with the even shorter 5’3” Yale “Midget” Murphy. Murphy held the position for about two months before the absence of Fuller’s fielding had Fuller back in his starting shortstop role.

Murphy, who is tied with several other ballplayers as the shortest man to have played regularly for a major league team, hit .272 for the year and played some games in outfield after Fuller’s return to shortstop. Fuller himself hit .276 for the year, but the league averaged .309 in 1894.

Fuller’s improved batting in 1894 resulted in his leading off or batting second for most of the 1894 and 1895 seasons. Fuller hit only .225 in 1895, although he did have an OBP of almost 100 points higher at .323. His low batting resulted in speculation that Fuller would not be the starting shortstop for the Giants in 1896. The Giants signed Frank Connaughton for the position.62 As the year developed, Fuller got into only 18 games. Sporting Life pointed out that Fuller had not been playing the field in his ordinary style and he was not hitting.63 Fuller batted .167 in those 18 games but did have an OBP of .310.

The Giants released Fuller on June 6, 1896.64 The press expressed some concern that the Giants had been too hasty and had been kicking themselves ever since.65 The New York World reported that Fuller’s release was primarily a cost-saving measure by the Giants.66

Fuller reportedly had offers from other major league teams notwithstanding his weak hitting,67 and one of those teams was St. Louis.68 He joined the Springfield Massachusetts Ponies in the Eastern League instead. He promptly booted four balls in a game on June 29.69 Noting his poor play, the Buffalo News speculated his days of usefulness on the ball field might be over.70 Fuller’s play recovered, and he continued with Springfield for the remainder of the 1896 season.

Fuller held out at the beginning of the 1897 season71 but ultimately signed with Springfield again. He then hit .252 in 120 games. Springfield released Fuller before the 1898 season, with the Buffalo Enquirer reporting that the proposed replacements were not worthy of tying Fuller’s shoelaces.72 Fuller then played a few games with the Detroit team in the Western League.

Fuller’s professional career ended with this brief stint in Detroit. He reportedly was claimed by the Columbus team for 1899, but he did not appear with them.73 It was also reported that he intended to try and play the 1900 season professionally, but nothing materialized for him.74

Sometime after 1900, Fuller’s health began to fail due to tuberculosis. His decline accelerated in early 1904. Fuller died on April 11, 1904. The disease may have been exacerbated by his work as a plasterer. Tuberculosis had already killed three of Fuller’s siblings within a four-week period at the end of 1895, including his brother Harry at age 33, and sisters Rose (age 16) and Mary (age 24).75 His sister Katie died of the disease at age 20 in 1897.

The Cincinnati Post headlined his death with “Famous Shortstop Out of the Game Forever—Little ‘Shorty’ Fuller, Who a Few Years Ago Won Applause Wherever New York Team Played, Dies at His Cincinnati Home.”76 The article goes on to note that his “name was on every fan’s tongue. He was the idol of the bleacher god of the old New Yorks and was the idol of the grandstand fan. When he came to Cincinnati he was remembered as a Cincinnati boy, and the applause for him was unstinted. He shared the applause with the players of the home team. … He played until ill health drove him from the ball field. But he kept up good cheer, and when his end came, he met it as bravely as he met the swiftest pitch ever sent across the plate to him. … Many friends are arranging to attend the funeral of the little man who ranked foremost among the ball tossers of years gone by. He was 38.”

Fuller’s death certificate names him as Ben Fuller and his age at death as 38. He is buried in St. Joseph’s (Old) Cemetery in Cincinnati in the Foeller family plot under the name Bernard Foeller, along with his parents, brother Harry (under the name Heinrich Foeller) and sisters Annie, Mary, Katie and Rose. The grave is no longer marked, and it appears there are no remaining direct descendants of the family.77

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Ray Danner. The author would like to express his appreciation for Jim Minervino’s background research on Fuller and his family in Cincinnati.

Sources

In addition to the sources included in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com, Baseball-Almanac.com, and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 “Shorty Fuller Did Great Work for New York,” Buffalo Morning Express, August 21, 1895: 10. The article notes that, “The wonderful play of Shorty Fuller was all that saved the New Yorks from defeat in their game with the St. Louis Browns today.” Fuller was batting lead-off, and he also had four assists in the game, meaning he had a hand in more than half the outs in the nine-inning game. According to Baseball Almanac Fuller’s record was tied by Joe Cassidy of the Washington Senators on August 30, 1904 and Hod Ford of the Cincinnati Reds on September 18, 1929.

2 “The Shortstop Did It—Wretched Fielding Responsible for Loss of Yesterday’s Game,” (Washington, DC) Evening Star, August 18, 1888:8. According to Baseball Almanac, Fuller was joined in infamy by shortstops Ray Chapman of the Cleveland Naps on August 20, 1914, and Lennie Merullo of the Cubs in his rookie season on September 13, 1942.

3 “Lost by Miserable Fielding,” Philadelphia Times, August 18, 1888: 6.

4 “The Shortstop Did It.”

5 “The Browns ‘Fuller’ Than Ever,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 17, 1889: 8.

6 “History Shows Giants Always Strong at Shortstop – Fuller Stood Out,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 10, 1935: 41.

7 “Toporcer on Pedestal St. Louis Has Set for Its Shortstops,” St. Louis Star & Times, May 20, 1922: 10.

8 The date of 1867 used on many baseball websites at the time of this posting appears to come from Fuller’s obituary in Sporting Life (“Shorty Fuller Dead,” April 23, 1904: 8), which lists his age at death as 36. Sporting Life may have been relying on the 1890 census, in which Fuller’s date of birth was listed as 1867. In that census, Fuller is listed as William B. and as the head of household with his older sister Annie as the other occupant. Most likely Annie provided the date of birth information while Fuller was away. The census lists Annie’s own (correct) birth year as 1857, which corresponds with the 1870 census. But Shorty was only 8 years younger than his sister based on that census, and a birth date of 1867 would have made him 10 years younger and the same age as his (deceased) younger brother Frank. Quite possibly, Frank’s birth year rather than Shorty’s was inadvertently listed on the census form.

9 Kate Foeller died on September 4, 1873, from puerperal fever which caused many deaths from childbirth during that time.

10 “The Last of Shorty Fuller,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 13, 1904: 4; “Famous Shortstop Out of Game Forever,” Cincinnati Post, April 12, 1904: 4.

11 “Yesterday’s Game,” (Zanesville, Ohio) Times Recorder, September 2, 1885: 1. “Shorty Fuller in Town,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 21, 1889: 10.

12 “Opening Game with Cincinnati Clippers,” Times Recorder, May 27, 1886: 4; “Notes,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 3, 1886: 2.

13 “Amateur Baseball,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 22, 1914: 20; “Notes,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 29, 1885: 10; “Notes,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 27, 1886: 5.

14“The National Game,” (Danville) Kentucky Advocate, August 31, 1886: 2; “‘Shorty’ Fuller in Town,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 21, 1889: 10.

15 “Sporting Events,” (New Orleans) Times-Democrat, March 7, 1887: 3.

16 “They Did It,” (New Orleans) Times-Picayune, August 9, 1887: 3.

17 “Lucky Thirteen,” Times-Picayune, September 8, 1887:8.

18 “Fourteen to Three,” Times-Democrat, August 1, 1887: 3.

19 “Shorty Fuller Signs,” Times-Picayune, October 27, 1887: 3.

20 “Four Straight,” Times-Picayune, May 6, 1887: 2; “Crippled and Crushed – The Demoralized and Battered Up New Orleans Nine,” Times-Picayune, May 14, 1888: 2.

21 “Sullivan’s Sharp Game – How He Secured Fuller from the Southern League,” Philadelphia Times, July 22, 1888: 16.

22 “The Fuller Case – Manager Ted Sullivan’s Slick Work,” Times-Picayune, July 14, 1888: 2.

23 “The Fuller Case – Manager Ted Sullivan’s Slick Work.”

24 “The Crescent City Players,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1888: 1.

25 “Sale of New Orleans Players,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 15, 1888: 11. The article suggests that New Orleans may have wanted $1,500 for all three players.

26 “Sullivan’s Sharp Game.”

27 “New Players Signed,” (Washington, DC) Evening Star, July 14, 1888: 8. Will White was a well-known recently retired pitcher with 40 or more wins twice in his career, but the reference appears to be to Bill White (also known as Will), who was the starting shortstop for the Louisville Colonels for several years and then the St. Louis Browns. The Colonels had recently released White and were in the market for a shortstop. See “The Fuller Case – Manager Ted Sullivan’s Slick Work”.

28 “Diamond Dust,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 8, 1888: 7; “Around the Bases,” Times-Picayune, August 31, 1888: 3.

29 “Baseball Small Talk,” (Washington, DC) Critic and Record, August 18, 1888: 4.

30 “Around Home Bases,” Times-Picayune, July 28, 1888: 3.

31 “Fuller’s Lightning Work,” Evening Star, July 21, 1888: 8; “Costly Errors,” Evening Star, August 4, 1888: 8.

32 See Transactions section in Fuller’s Baseball Reference entry. “At St. Louis,” Philadelphia Times, December 30, 1888: 16. The Times reported that the price was under $1,000.

33 “Diamond Dust,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, December 30, 1888: 11.

34 “The Browns ‘Fuller’ Than Ever,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 17, 1889: 8.

35 “The Browns ‘Fuller’ Than Ever.”

36 David Nemec (editor), Major League Baseball Profiles 1871-1900 Volume 1-The Players Who Built the Game (Lincoln Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2011): 458.

37 “Base Ball Briefs,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 22, 1889: 10.

38 “Base Ball Notes,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 17, 1889: 5.

39 “Base Ball Briefs,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 24, 1889: 8.

40 “Diamond Dust,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 23, 1889: 11; “The Giants Champions,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 6, 1889: 5.

41 “Sporting,” Buffalo Enquirer, July 14, 1898: 6.

42 “Sporting,” Buffalo Enquirer, July 6, 1898: 6. The four infielders played a single season together on the Browns in 1889, but catcher Bushong was playing for Brooklyn that season, after having been replaced by Jack Boyle as the Browns starting catcher in mid-1887. Bancroft may have conflated some seasons or employed some poetic license in using Doc Bushong as the catcher in this anecdote.

43 “Sporting,” Buffalo Enquirer, August 11, 1896: 8. It is possible that an interference call reported on Fuller when he played for the Giants may have related to such a tactic. “It is Brooklyn’s Series,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 17, 1895: 4.

44 “A New Brown Stocking,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 20, 1889: 13.

45 “At Sportsman’s Park,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 7, 1890: 8; “Beaten by Reds,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 8, 1890: 10.

46 “Base-Ball Gossip,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 11, 1890: 8.

47 “Base Ball Briefs,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 8, 1890: 8.

48 “Base Ball Notes,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 13, 1890: 24.

49 “A Hard Ball Game to Lose,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 17, 1890: 9.

50 “Base-Ball Briefs,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 15, 1890: 8.

51 “’Shorty’ Fuller in Town,” above; “Fuller on the Browns,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 2, 1891: 8.

52 “Base Ball Menagerie – The Fun President Von der Ahe Is Having with His Wild Animals,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 18, 1890: 10.

53 “Base Ball Notes,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 29, 1891: 8.

54 “Hits Inside the Diamond,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 3, 1891: 8.

55 “Washington 7; St. Louis 4,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 20, 1891: 6.

56 “The St. Louis Players,” Pittsburg Dispatch, November 26, 1891: 8.

57 “Sporting,” Cincinnati Post, December 15, 1891: 6.

58 “Sporting,” Cincinnati Post, April 29, 1892: 4, quoting Sporting Life.

59 “Crane’s Erratic Work,” (New York) World, May 5, 1893: 6. Fuller had nine assists and a putout in the game.

60 “Only One Run Was Scored,” New York Times, May 30, 1893: 3. Fuller had eight assists in the game. See also, “New York and Brooklyns Break Even at Eastern Park,” Brooklyn Citizen, June 29, 1892: 3.

61 See, e.g., “Shorty Fuller Did Great Work for New York,” Buffalo Courier Express, August 21, 1895: 10 (the game in which he recorded a record-setting 11 putouts and also four assists); “‘Shorty Fuller’ Played Magnificently at Short and Batted in Fine Style,” (New York) Evening World, June 20, 1894; “Fuller’s Fine Work Fails to Save Game at Philadelphia,” World, October 15, 1892: 6.

62 “Hanlon’s Views on the Giants,” Illustrated Buffalo Express, January 12, 1896: 19.

63 “New York News,” Sporting Life, May 28, 1896: 10.

64 “News and Comments,” Sporting Life, June 13, 1896: 5.

65 “Sporting Notes,” World, July 6, 1896: 10; “W.B. (Shorty) Fuller,” Buffalo Enquirer, September 26, 1896: 8.

66 “All Hail Cincinnati,” World, June 8, 1896: 8.

67 “Baseball Pickups,” Buffalo Enquirer, June 10, 1896: 8.

68 “Diamond Points,” Brooklyn Times, June 9, 1896: 6.

69 “Fuller and Reilly Responsible,” Buffalo Courier, June 30, 1896: 5.

70 “Baseball.” Buffalo News, July 10, 1896: 6.

71 “Latest Sporting News,” Buffalo Times, March 7, 1897: 15.

72 “Sporting,” Buffalo Enquirer, April 22, 1897: 6.

73 “Johnson’s Teams,” Buffalo Commercial, February 1, 1899: 4.

74 “Baseball Notes,” (Rochester, New York) Democrat and Chronicle, December 18, 1899: 14.

75 The unusual clustering of deaths from tuberculosis in the family suggests that tuberculous meningitis may have been involved, or that influenza or another respiratory condition contributed to their deaths, although no contributing factor beyond tuberculosis is mentioned on any of their death certificates. Harry had played in 107 games for the Portsmouth Truckers in the Virginia League in 1895, so it appears his disease advanced quickly.

76 Cincinnati Post, April 12, 1904: 4.

77 None of the Foeller siblings married, with the possible exception of Lizzie, who disappears from the record in Cincinnati after the 1880 census and several possible mentions in the city’s directories in the following decade.

Full Name

William Benjamin Fuller

Born

October 10, 1867 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

April 11, 1904 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.