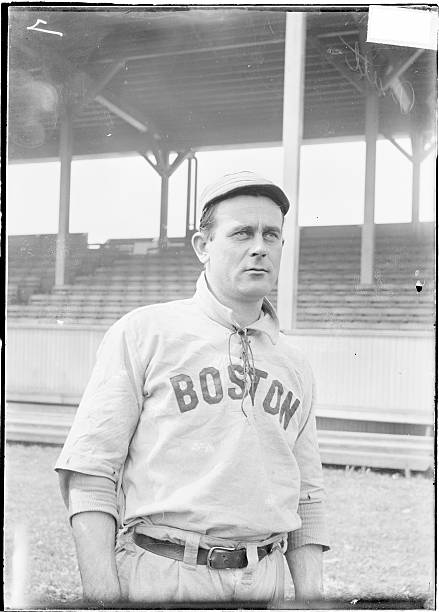

Wiley Piatt

Wiley Piatt burst onto the major-league scene in 1898 with the Philadelphia Phillies. With just one year of minor-league ball on his resume, he tossed over 600 innings the next two seasons and won 47 games while orchestrating 64 complete games. None of those heroics earned him a lasting nickname. That had to wait until 1903 when, at the tail end of his career, he pitched complete games in both ends of a June 25 doubleheader for the Boston Beaneaters. Fans quickly dubbed him “Iron Man.”

Wiley Piatt burst onto the major-league scene in 1898 with the Philadelphia Phillies. With just one year of minor-league ball on his resume, he tossed over 600 innings the next two seasons and won 47 games while orchestrating 64 complete games. None of those heroics earned him a lasting nickname. That had to wait until 1903 when, at the tail end of his career, he pitched complete games in both ends of a June 25 doubleheader for the Boston Beaneaters. Fans quickly dubbed him “Iron Man.”

The nickname was very popular at the time. Joe McGinnity had made pitching both ends of a twin bill fashionable beginning in 1901 and was often called “Iron Man” in the press. In August 1903 he turned the trick three times. The difference between McGinnity and Piatt is that Joe always won the first game of the day. Piatt is the only major-leaguer to lose both complete games he pitched.1

Wiley Harold Piatt was born on July 13, 1874, in Adams County, Ohio, near the small community of Blue Creek, joining his siblings, William and Arpha. His parents were Francis and Henrietta (Grooms) Piatt, who were both of French Huguenot descent and had been in Ohio for many years. Francis was a second-generation blacksmith. He was probably working with his father, Lewis, in their shop in Jefferson Township, Adams County, at the time of Wiley’s birth.

How much schooling the children received is unknown. William was working as a farmhand at the age of 15. Wiley was identified as a teacher when he reached the major leagues at age 23.2 Baseball-Reference lists him as attending Ohio University. A check with the University did not reveal him on their class rolls. Wiley probably never set foot on the Athens, Ohio, campus. He attended the Normal College in Peebles, Ohio, that was associated with the University. Normal colleges were teacher-training centers and were scattered about the state. Attending school and then teaching would explain why Piatt was 22 before he turned to professional baseball.

We do know that Wiley developed into an excellent athlete who stood 5-foot-10 and weighed 170. He was left-handed at bat and on the mound. He was an excellent hitter and showed good speed on the bases. Piatt possessed quite an ego. He told a newspaperman that he was at ease playing in the majors. It did not matter to him if it was “Baltimore or West Union, Ohio. He always had his nerve with him.” 3

Piatt must have been an intelligent fellow because in addition to teaching before joining the professional ranks, he worked in a law office during the winter of 1898-99. As with many young ballplayers, especially pitchers, his left arm and bat were in demand by teams in southern Ohio willing to pay for his services.

The town of Otway is in Scioto County about 15 miles from his birthplace. He often is identified as being from there and even had “Wiley Piatt, Star Pitcher of the Otway team” printed in large letters on his travel bag.4 He was supposed to play with Portsmouth, Ohio, in 1897 but that team disbanded.

The Pittsburgh Pirates sent him a ticket to join them, but he turned down the opportunity and returned the ticket. He was contacted by Maysville, Kentucky, and in late July traveled to Knoxville, Tennessee, to pitch for Maysville, losing, 5-4, on July 22.

Shortly after his return to Ohio he was signed by the Dayton Old Soldiers of the Interstate League. Piatt was probably recommended by third baseman James McShane, who had played with him previously.5 Piatt arrived in Dayton on August 10 and took up residence in the Phillips Hotel. He made his professional debut the next day against Toledo, holding the Swamp Angels to four hits over the first six innings, leading, 4-3. He featured a puzzling mix of curves to go with his fastball. Having been out of action for a couple of weeks, he tired and surrendered seven runs in the seventh and eighth on the way to a 10-9 loss. The local newspapers and fans blamed the manager for offering no relief. Toledo manager Charles Strobel agreed that Piatt was a good man and a mistake was made leaving him in the game.6 Piatt slapped a single and double in five trips to the plate.

Piatt took the hill again on August 15 versus Fort Wayne. He struck out 11, which was a league high for the year. At the plate he went 4-for-5 and hammered two triples in the 20-0 whitewash. That game was followed by a 5-1 loss to Toledo. For the season he piled up nine wins and three losses including three shutouts. Statistics posted in October credit him with an opponents’ batting average of .183, the best in the circuit. At the plate he was a wrecking ball for the six weeks he played. He went 18-for-41, a .439 average.7

He also pitched two exhibition games; the first he lost, 14-4, to Piqua. The Dayton team was upset with a biased hometown umpire and did not offer much effort after the first two innings. Piatt reportedly “floated straight balls over the plate.”8 He lost a contest to the Cincinnati Red Stockings, 11-3, on October 10. Later that month the Philadelphia Phillies drafted him along with teammate Elmer Flick.

Piatt’s fastball was very effective. He had supposedly fanned 22 in a semi-pro game in Cincinnati in 1896. One newspaperman claimed many years later that it compared with the heat Amos Rusie fired. That appears to be quite a stretch, but a Sporting Life article in 1898 did list him amongst the 10 hardest throwers. The most impressive thing about Piatt’s fastball was his control. He seldom suffered from bouts of wildness. The worst control he demonstrated for Dayton came when he surrendered four walks against New Castle on September 4 and was pulled after six innings.

Piatt and Flick joined Nap Lajoie, Ed Delahanty and the other Phillies for spring training in Cape May, New Jersey, in March 1898. Intrasquad games started in late March with a rule prohibiting curve balls until later in April. Piatt was used with the Yanigans and found himself playing outfield and even second base. He had a rough pitching outing on April 2 because the veterans had seen him pitch four out of five days and timed his fastball.

Manager George Stallings took his time in selecting a pitching staff. When the season opened, he tried different starting pitchers each day. Piatt’s first opportunity came on April 22 when he faced off with Amos Rusie and the New York Giants. Watching from the bench for a week made him a bit rusty. He had control problems, walking seven and hitting two. Fortunately, the Phillies were hitting Rusie hard. Piatt contributed a scratch single in the second inning to keep a rally going. Then in the sixth he reached on a slow roller to third. He scored both times and went the whole game to record his first victory, 13-7.

Piatt sat and watched the next two weeks before being sent in to relieve Davey Dunkle on May 9 in Washington. Piatt surrendered only two hits from the fifth inning on as the Phillies rallied for an 11-6 win. His performance earned him a couple of starts against Baltimore. He won, 5-4, on May 13 but was crushed on May 17 in a 17-2 loss.

In late May the Phillies finally settled on their pitching rotation of Red Donahue, Al Orth and Piatt. The threesome put in 100 starts and toiled over 840 innings. Piatt led the way with 306 innings and 33 complete games. He crafted a 24-14 mark that included two five-game winning streaks and six shutouts. After the season, Henry Chadwick noted that he had the second-best winning percentage against first division clubs.9 Early in the season the newspapers used the nickname “Lizzie” for him, but it failed to stick.

The Phillies’ 1899 spring training train pulled out of Philadelphia on March 15 headed for Charlotte, North Carolina. Piatt was in fine shape and quickly earned his place as ace of the six-man staff. He garnered the right to throw opening day on April 14 against the Washington Senators. Before 10,000 fans he came away with a 6-5 win.

By the end of May he sported a 7-3 record. His most interesting game early in the campaign came against New York on May 10. The affair lasted 11 innings with Philly coming out on top, 4-3. The local paper reported that 27 of the putouts in the game came on fly balls/popups. There were only 5 assists and two of those were by outfielders.10 Piatt was by no means a “fly ball pitcher.” A check of box scores reveals numerous games where his infielders handled 12 or more chances.

Piatt’s roughest outing came on July 22 in Pittsburgh. Third baseman Billy Lauder was injured, forcing pitcher Chick Fraser to play third base. Ginger Beaumont, the speedy lead-off batter for the Pirates, tested the hurler out by bunting. Fraser was helpless; Beaumont went 6-for-6 with five bunt hits in the Pirates’ 18-4 win.11 Fraser committed no errors, but his teammates contributed seven including one by Piatt.

Piatt bounced back with three straight wins. He captured his 23rd victory from Baltimore on September 23 then closed out the campaign with three losses to finish 23-15. He again led the team in wins, innings and complete games. His strikeouts dropped noticeably. Modern statistical methods show his pitching WAR was 4.6 in 1898. It dropped to 2.6, but that was still the best on the team in 1899.

Wiley split the off season between Ohio and Philadelphia. He fancied himself a scout and recommended Lou “Bud” Mahaffey to the Phillies. Mahaffey lived near Piatt in Adams County and had played briefly with the Louisville Colonels. He might also have recommended infielder Charlie Ziegler, who also hailed from Ohio.

Piatt boarded the team train in Philadelphia headed to spring training where he found himself once again assigned to the Yanigans for intrasquad games. He played more outfield than pitcher. When the actual exhibitions began, he pitched against Lafayette College and a couple of minor league teams. He pitched much less than he had in the previous pre-seasons.

Manager Bill Shettsline had put together a powerful team anchored by future hall of famers Ed Delahanty, Elmer Flick and Nap Lajoie. He had a five-man pitching staff of Piatt, Fraser, Donahue, Orth and Bill Bernhard. Veteran Al Maul rounded out the staff early in the season. The Phillies were hot at the start of the campaign. They quickly took first place only to drop into second when Piatt lost his first start versus Brooklyn. He was not sharp and even failed to run out a grounder because he was tired; perhaps his lack of activity in the pre-season was to blame.

The Phillies quickly regained first and stayed on top of the standings until mid-June when Piatt lost, 8-1, to the Giants. Piatt was struggling and had a 3-5 record at that point. Even when he won, his control was suspect; he walked six in his 11-7 win over St. Louis on June 13.

He found his groove in late June and won six of seven starts, but the Phillies had dropped off the pace and would never regain first place. In August he started to complain of physical issues and was given an extra day or two between starts. He still dropped three in a row. After his August 22 loss he was hospitalized in the Episcopal Hospital in Philadelphia with typhoid fever. The illness ended his season and the Phillies added Jack Dunn to replace him. He closed out the year with a 9-10 record.

The illness kept him in the hospital for nearly eight weeks. When he was released, he went to the Phillies office to pick up his final paycheck only to find that they refused to pay him for the last month because he had not played. He had a $240 hospital bill and no paycheck, and was also being refused a $300 bonus which he thought he earned with the June/July performance.12

Piatt returned to his home, but his problems did not end. In early December he was arrested in Portsmouth, Ohio, on a paternity charge. (The outcome of the case is unknown because the Flood of 1937 wiped out records.) At the end of the year he announced that he was through with baseball except for his support of the Players Protective Association. He announced that he would enter Ohio State University and study law. He also announced that the Players group had adopted a resolution denouncing the Phillies for holding his pay.13

The retirement and law school pronouncement proved to be a ruse. Piatt was courted by both the Phillies and the Athletics over the winter, keeping the telegraph operators busy in rural Ohio. Finally, he signed with Connie Mack in mid-March. He was joined by teammates Bernhard, Fraser and Lajoie in the new American League. The pitching staff was enhanced with the arrival of Eddie Plank in May.

Piatt started the second game of the season and lost, 11-5, to Washington. Earlier in his career Piatt had quipped that Baltimore did not scare him. That may still have been true in 1901, but they certainly had his number. He made three starts and a relief appearance against the Birds and met defeat by scores of 11-7, 8-5, 14-10 and 15-13. Cleveland was more to his liking; he had two wins and a save (by modern terms) against them.

Mack made some roster moves in July, dropping Piatt and two others. Piatt was just 5-12 with Mack’s men but, even so, his release came as a “surprise to many. Piatt’s supreme confidence in himself… was apparently not shared by his manager.” It was noted that when Piatt listened to his coaches and kept himself in shape, he was a quality pitcher. He was doing neither in Philadelphia.14

Piatt picked up some spending money in the Philadelphia area by playing semi-pro ball the next few weeks. The Chicago White Sox were in search of a steady left-handed hurler and signed him in late August. The baseball gods were having fun at Piatt’s expense when his first assignment came against his nemesis, the Baltimore Orioles. Wiley beat them, 5-2, in the second game of a twin bill on August 31. He returned to the hill two days later, again in a game two, and was pounded by his former teammates, 10-9.

With doubleheaders piling up on the schedule, Piatt pitched the second game three more times. He won two and lost one, including a 4-0 shutout in Milwaukee. His final two starts were single games. He lost to Boston on September 24 in a game the Sox did not take seriously because they had clinched the pennant. Piatt closed out the season with a 6-4 win in Washington.

He returned to Ohio for the off season. Some sources reported that he was sick, possibly with smallpox.15 Regardless of his physical condition, he was looking for the best contract he could find. His search got him into hot water when he assured George Stallings that he would play for Buffalo in the Eastern League then turned around and signed a contract with Chicago. Stallings petitioned the National Association to blacklist Piatt.16 No action was taken to penalize him.

Weakened by his illnesses, Piatt earned the reputation as a seven-inning pitcher. Papers had begun to refer to the eighth as the “fatal eighth” because of his numerous late inning losses.17 There was even speculation that the Sox would use him in tandem with Ned Garvin, who also had the reputation as a seven-inning man. As the only left-hander, Piatt was given his regular turn, making 30 starts and tossing 22 complete games on the way to a 12-12 mark.

Consistency was his problem. He tossed shutouts versus Boston and St. Louis but might turn in a seven-walk performance as he did against the Tigers on May 11. One of his better performances was a 2-1 win over St. Louis on May 16 when he struck out a season-high 8.

His confidence wavered a bit and he spoke to reporters about it. He feared his arm was giving out and that he might only have two years left. His explanation was that a left-hander’s arm was closer to the heart than a righty’s and “wears us out quicker.” He admitted that he had a fault with his control. “Try as hard as I’m a mind to, I can’t get that first ball pitched to the batter over the plate.”18 Despite Piatt’s misgivings he happily signed a contract to jump to the Boston Beaneaters in 1903. They offered him $4300 to make the switch.19

The overpaid Piatt became a scapegoat for the poor Boston performance in 1903 when they finished in sixth place. He posted a 9-14 record by mid-July and had the poorest fielding percentage of all National League pitchers. The Beaneaters acquired lefty Pop Williams and pulled Piatt from the rotation. He was released after a relief stint on August 1. His release saved Boston about $1000 in salary.

His brush with the record book came on June 25 when he lost the first game of the day, 1-0, to St. Louis. The visitors punched two singles around a sacrifice in the fifth to score their run. Piatt walked one and struck out seven. He started the second game in a drizzle that did not let up. The Birds put five runs on the board in the second when they bunched singles with a couple of Ed Gremminger errors for five unearned runs. Boston dropped the contest, 5-3. The St. Louis beat writer noted Piatt “deserves credit for pitching eighteen innings of good ball.”20

After his release Piatt attempted to hook on with another organization. There was speculation that he might join Cleveland. On September 1 it was reported that the Buffalo Bisons and George Stallings had signed him and Scoops Carey for a late-season push. Once again Piatt disappointed Stallings and was a no-show. He was playing semi-pro ball in New England after his release and when the Stallings offer came in, he was in Lebanon, New Hampshire, reportedly making $150 a week plus expenses.

Piatt returned to Otway and married Lola Scott on October 15, 1903.21 The marriage lasted until 1906 when Lola filed for divorce on the grounds of cruelty and desertion. Piatt contemplated a return to New Hampshire in 1904, but then joined the Nashville Volunteers in the Class A Southern Association.

He led the Volunteers’ staff in appearances and was second with 18 wins (against 22 losses) and tossed four shutouts for the fifth-place squad. On the 4th of July he pitched both ends of the doubleheader against Birmingham, dropping the first game, 5-4, but rebounding with a 6-0 shutout in the second match. He and Lola were living fulltime in Nashville. He was arrested and fined $25 in November on a drunk and disorderly charge. It might have been a more serious case but Lola, who had allegedly been beaten into unconsciousness, refused to file charges.22

Piatt was released by Nashville during the winter and signed with the Paducah, Kentucky, Indians in the Class D Kitty League. By all accounts Piatt had a sensational season and earned the title of “King of the Kitty.” His dominance was no surprise for a player with talent who drops into a low classification. Paducah sold him to Toledo on August 8, about ten days before the league disbanded because of a yellow-fever outbreak and general poor finances. According to the local paper, he left town with a record of 23-3; 17 of the wins were shutouts and he supposedly pitched and won three doubleheaders. Five of those games were shutouts.23 His most impressive win came May 9 against Henderson when he pitched a 5-0 one-hitter. The only runner was retired; Piatt faced the minimum 27 batters, striking out 13.

Toledo in the American Association paid $400 to obtain Piatt’s services. When the Mud Hens sold Win Kellum to Minneapolis, Piatt, now 30 years old, became the staff veteran and only lefty. Doubleheaders were piling up and Piatt became a workhorse. He beat last-place Kansas City three days in a row. In less than six weeks (August 11 to September 18) he posted a 9-5 record including two shutouts and a win over first-place Columbus. His batting eye took a liking to the league pitchers and he slammed a career high (to that point) four doubles.

Piatt returned to Toledo in 1906. While the team improved by 19 wins, Piatt was unable to match his performance and stood at 9-10 when he was released. He hit .288 and slammed seven doubles. Paducah picked him up, but he was nothing like the man they had the year before. His arm was giving out as he had predicted, plus he was medicating himself from the bottle.

His career hit a low on September 4, 1906, when he got into an altercation in Vincennes, Indiana, with a fan named Frank Dollihan. Piatt “objected to his rooting” in an insulting verbal tirade. Dollihan grabbed a bat and hit Piatt three times; one over the left ear “felled Piatt, inflicting what may prove to be a fatal injury.”24 Piatt was back in action the following week.

After his divorce in 1907, Piatt signed on with the Sally League but was released on May 10. He caught on with Sumter in the independent South Carolina State League and returned to Ohio when that season ended.

Piatt journeyed south again in 1908 and started the season with Charlotte in the Class D Carolina League. He pitched brilliantly in his first outing, a 5-1 win over Spartanburg. After that he was found wanting and was dispatched to Spartanburg in late May. On June 5 he led Spartanburg to a 7-2 win over Charlotte. His glory was short-lived; he was given his pink slip on June 23.

He joined the Portsmouth squad in the Ohio State League in 1909 but was released in the second week of May and played semi-pro ball in the Cincinnati area until returning to Portsmouth on June 1. After a couple poundings he was released again. Piatt tried umpiring in the Kitty League in 1911 and lasted about six weeks. In 1913 he attempted a comeback with Paducah, but it was obvious that he had nothing left.

Wiley was married in 1908 to Lestia Ann Piatt, a cousin. They would have three children: Bernice, Evelyn, and Harlan. In 1920 they resided in Adams County and Wiley was working as a farmer and did carpentry. The 1930 census listed Wiley again as a farmer in Tiffin Township, but Lestia and the children were living apart from him with her brother, Benny Piatt. Both Lestia and Wiley listed themselves as married on the census form. They divorced sometime in the 1930s.

Piatt married a third time, to Lutie Ann Hay from the Maysville, Kentucky, area. At the time of the 1940 census they lived in Augusta, Kentucky, about 40 miles west of Tiffin Township. Piatt then moved to Dayton, Ohio, during the war and worked in the sheet metal shop at Wright Field (now Wright Patterson Air Force Base).25 He was hospitalized in Cincinnati with cancer and died from complications on September 20, 1946. He was buried in Augusta. At some point his body was removed and reinterred in the East Liberty Cemetery in Adams County where many of his family members are buried.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Brenda Cox in the Ohio University Registrars Office and Bill Kimok in the Ohio University Archives for their help. Thank you to ancestry.com members cindyanna4 and lapiatt101 for their assistance with details of Piatt’s personal life.

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Leonard Gettleson, “Iron Man Pitching Performances,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 6, 1977. Accessed online at http://research.sabr.org/journals/iron-man-pitching on January 9, 2019.

2 “Local Jottings,” Sporting Life, October 16,1897: 4.

3 “A Stayer,” Portsmouth (Ohio) Daily Times, May 14, 1898: 3.

4 Pete Minego, “Minego’s Sports Gossip,” Portsmouth Times, February 22, 1952: 6.

5 “Something in Regards to the Southpaw Recently Signed with Dayton,” Dayton Herald, August 10, 1897: 6.

6 “Notes,” Dayton Herald, August 12, 1897: 6.

7 “Interstate Averages,” Cleveland Leader, October 11, 1897: 3.

8 “Base Ball Notes,” Portsmouth Daily Times, September 27, 1897: 3.

9 “Pitcher’s Work, Sporting Life, January 21, 1899: 2.

10 “Passed Balls,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 11, 1899: 7.

11 “Phillies Play Wretched Ball,” The Times (Philadelphia, Pa.), July 23, 1899: 12.

12 “Back to Hospital,” Dayton Daily News, October 20, 1900: 3.

13 “Pitcher Piatt to Quit, “Pittsburgh Daily Post, December 31, 1900: 6.

14 “Mack Makes Several Changes,” The Sporting News, July 20, 1901: 6.

15 “Baseball Gossip,” Buffalo Enquirer, March 29, 1902: 4.

16 “Piatt Blacklisted,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 30, 1902: 10.

17 “Piatt Steady in the Eighth,” Chicago Tribune, May 22, 1902: 13.

18 “Short-Lived Southpaws,” Salt Lake Tribune, June 8, 1902: 20.

19 “Piatt Signs with Boston,” St Louis Post-Dispatch, August 25, 1902: 3.

20 “Piatt Pitched Both Games,” St. Louis Republic, July 26, 1903: 10.

21 I have seen Lola and Lois. Harlan Piatt listed Lola Scott on the questionnaire he did for the HOF.

22 “Wiley Piatt Fined,” The Tennessean (Nashville, Tn), November 15, 1904: 7.

23 “Piatt Sold,” Paducah News-Democrat, August 9, 1905: 1.

24 “Wiley Piatt Injured,” Princeton Daily Clarion (Princeton, Indiana), September 5, 1906: 3.

25 George Harr, “When Wylie Piatt Pitched, the Boys Went Down 1-2-3,” The Journal Herald (Dayton, Ohio), February 25, 1944: 6.

Full Name

Wiley Harold Piatt

Born

July 13, 1874 at Blue Creek, OH (USA)

Died

September 20, 1946 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.