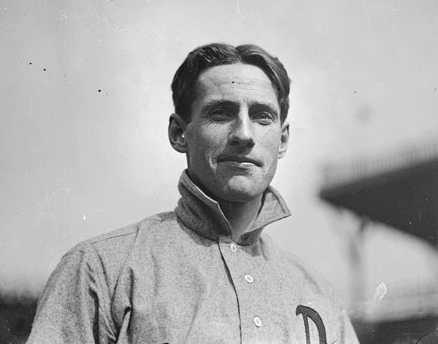

Andy Coakley at Columbia

This article was written by Tara Krieger

Columbia University went through six baseball coaches in eight years from 1906 through 1913. But in 1914, former big league pitcher Andy Coakley joined the program, handling pitchers and catchers. He became the Lions’ head coach in 1915 and remained in that job for 37 years, stepping down after the 1951 season. Coakley shaped the lives of hundreds of players who donned the Columbia Blue and White — most notably, Lou Gehrig, whose future in baseball he quite possibly saved.

Columbia University went through six baseball coaches in eight years from 1906 through 1913. But in 1914, former big league pitcher Andy Coakley joined the program, handling pitchers and catchers. He became the Lions’ head coach in 1915 and remained in that job for 37 years, stepping down after the 1951 season. Coakley shaped the lives of hundreds of players who donned the Columbia Blue and White — most notably, Lou Gehrig, whose future in baseball he quite possibly saved.

Looking to be more competitive, on February 18, 1914, Columbia announced for the first time it was splitting the baseball coaching duties between two men, both ex-major leaguers.1 Billy Lush was head coach, and Coakley, who’d pitched for four major league teams between 1902 and 1911, and had coached the previous three seasons at Williams College, worked with the batteries. The Lions, who had graduated many of their stars from the previous season, finished 10-7.

One of the players who went out for that 1914 squad was the son of Hall of Famer Ned Hanlon, who according to one account, couldn’t bunt. “It’s a good thing your ‘dad’ didn’t see that,” said Coakley. The younger Hanlon retorted, “If I don’t know how to do it better when he sees me, you’re not much of a coach.”2

Columbia was impressed with how Coakley had handled its pitchers, including ace Eddie Shea. Thus, “after weeks of dickering with Billy Lush,” (as Sporting Life put it), Columbia athletics manager Grant Stone announced that the university had snapped up Coakley to be head coach for the 1915 season.3

Habitually open to innovation, Coakley had an indoor sliding device — a canvas made of white lead and wax, and several moveable batting cages installed in the gymnasium. For the first time, the baseball team could practice in the dead of winter before the basketball season had ended. Although Coakley did not actually invent the sliding device, he might have been the first to use it.4 Coakley also added a few indoor scrimmages to the schedule in January and February. He assigned the pitchers to work with the crew coach on the rowing machines to strengthen their arms.5

It apparently did something, as Columbia finished 13-6-1, though some reports indicate that the team actually underachieved, thanks in part to discord between Coakley and team captain Jimmy O’Neale. Coakley’s laissez-faire attitude as a way of resolving disputes among his players drew criticism about whether he was capable of “holding the team together.”6

But those concerns were put to rest the following year. Coakley considered the 1916 team the greatest he ever coached, “as it was the first and only team in which I could employ major league tactics.”7 The team went 17-1-1 in the years before any formal collegiate league or title existed, and three players — second baseman and captain Bobby Watt, shortstop Mike “Bunny” Buonoguro, and pitcher George Smith, were offered major league contracts at the end of the season, though only Smith actually signed.8 Smith played for four teams in eight seasons, half of them with the cellar-dwelling Philadelphia Phillies, and earned a reputation as a journeyman pitcher (41-81, 3.89 ERA). To date, no Lion has enjoyed more success on a major league mound than “Columbia George.”

Also on the team was pitcher Don Beck, whom Coakley described years later as “perhaps the greatest ball player I coached at Columbia.” Beck decided to study medicine, in spite of strong interest from professional clubs. “He’s a fine doctor,” Coakley said 35 years later. “He’s my own physician.”9

Few questioned Coakley’s ability to hold a team together afterward, and he was signed to a multiyear deal with a pay bump.10 His obituary in the New York Times highlighted his mild use of authority as an asset. He made his expectations clear, but he preferred not to impose rigid restrictions on his players, believing that the more rules he created, the more they would be broken.

“The worst thing they do is drink too many ice cream sodas,” he lamented.11 It’s unclear when Coakley said this, or if he was naïve enough to believe it. Prohibition was in effect for a large part of his coaching career.

This may not have been universally true. In a preseason meeting in 1917, Coakley stressed the importance of staying in shape and advised all his players to be in bed by 11 o’clock. Any player caught drinking or smoking would be expelled from the team.12 Perhaps Coakley loosened up with age; by 1928, he was lecturing players that while punctuality was important, “Don’t get the idea, however, that this is a game of life and death. Get fun out of it; make it play, not work; and win or lose, have a good time.”13

John McCormack, who played for Coakley in 1937, said he “never heard Andy raise his voice or utter a foul word. He was always well dressed.

“He was on a first-name basis with his players,” McCormack continued. “When we spoke I was ‘Mac’, he was ‘Andy’. Since the players respected him even though we called him ‘Andy’, he had full control of the team.”14

The father-son relationships he fostered over the years with his players may have been, in part, due to his own longings as a parent. Coakley’s only child, Kathleen, died at age 10 in 1921. He rarely spoke of her.15

With America’s involvement in World War I and the threat of a draft imminent, Columbia followed the trend of many major league clubs in the spring of 1917 and added military training drills to their workout routine.16 A week after the US declared war in April, Columbia, Cornell, Harvard, Princeton, and Yale canceled all their intercollegiate athletics. The Lions’ season was curtailed at three games.17

That summer, the National Collegiate Athletic Association reversed the edict, and Columbia baseball resumed in 1918. 18 The team struggled, finishing 5-9-1, and halfway through the season, Coakley learned he wouldn’t be back. Instead, football coach Fred Dawson would also be taking over baseball and basketball.19

Some Columbia students rued the changing of the guard.20 But Coakley likely did not suffer financially. Coaching was a part-time position; his bread and butter for most of his career and thereafter was selling insurance.21 Other business pursuits included semipro ventures; he coached and continued to pitch in semipro games on occasion.22

Coakley’s sabbatical from Columbia did not last long, however. By the fall of 1919, he had been rehired as an assistant coach. Two months later, Dawson resigned from athletics, citing poor health, and Coakley was the natural successor. In 1920, Coakley was back where he belonged. The next year, he signed a three-year deal.23 When that ended, he signed another.24

Coakley generally fielded mediocre to decent squads throughout the 1920s. His best year of the decade was 1926, at 17-5; the worst was 1929, at 4-12-1. He saw two more of his former players reach the major leagues. One was pitcher Art Smith (1928), who had a cup of coffee with the White Sox in 1932. Gehrig was the other.

In June 1921, a burly first baseman named “Lewis” began appearing in the Hartford sports pages for its Eastern League team, the Senators. Within two weeks, word reached the Columbia campus that this was the same kid who had accepted an athletic scholarship for the upcoming fall. Coakley had seen him about campus since he was a lad running errands for his mother, a cook at Columbia’s Sigma Tau Delta fraternity house.

Something had to be done. Whether Coakley made the 3½-hour train ride from New York to Hartford or Watt, now the Columbia athletic director, went on his behalf depends on what version of the story is being told. But the result was the same: the shy, embarrassed kid came home.

Days away from his 18th birthday, Lou Gehrig had some 50 pounds of muscle on his future coach, but he must have felt a fraction his size.

Not one to raise his voice or lose his temper, Coakley spoke sternly and evenly. Did Gehrig not realize that by donning the uniform of a professional team, even under a fake name, he was jeopardizing his athletic eligibility and a scholarship for an entire four years of a good college education?

And yet Coakley understood completely the lure of a paycheck and an empty promise that no one would find out. Not two decades earlier, he had ceded his own collegiate athletic eligibility by using a pseudonym. He could not be sure what would result from Gehrig’s transgression.

Coakley and Watt pleaded vigorously on Gehrig’s behalf to both the Columbia trustees and the school’s opponents that it was an innocent mistake. The schools eventually arrived at a compromise: Gehrig would retain his scholarship, but would be suspended from collegiate competition for one year.

Two years later, New York Yankees scout Paul Krichell discovered Gehrig pounding long home runs and signed the sophomore to a major league contract.

Coakley has received a startling amount of credit for grooming Gehrig into professional-ready status. Gehrig biographer Ray Robinson, who graduated from Columbia in 1941 and superficially knew Coakley, thought the praise was overblown. “You’d have to be blind not to realize the talent right in front of you,” he said.25

Gehrig’s one season with the team came in 1923, after he was redshirted his freshman year due to his aforementioned professional stint. His seven home runs and .444 batting average (28-for-63) were Columbia season records, since surpassed. The legends endure of his 400-foot clouts, from South Field to the Low Library steps and the inside of the Journalism building, as well as off the Columbia sundial. He slugged a mind-boggling .937.

He could also pitch, fanning at least ten batters in five of his 11 appearances on the mound that season. He struck out 17 in a losing effort against Williams College on April 18 , a Columbia record that as of 2018 has been equaled, but not surpassed.

Coakley also claimed that in spite of Gehrig’s size, he was quick on the base paths, running 100 yards in less than 11 seconds, and that he possessed a “sureness of hand.” The latter was something Coakley helped him refine, feeding him hundreds of ground balls to correct his slow timing and sluggish reflexes.26

“Lou was a natural,” Coakley said “The boy always loved to play ball. And could he hit. I remember his last game against NYU in 192[3]. Lou caught an inside pitch and pushed it toward right field. Home plate was near the corner of South Field next to Butler Library. The ball traveled on a line toward right, and finally bounced on the top steps of Low Library, barely missing Dean [Herbert] Hawkes by inches. Immediately after that blow, Yankee scouts, who were among the spectators, signed Gehrig to a major league contract.”27 The rumor was that Coakley was paid $500 to encourage Gehrig to drop out of school; it remains a rumor. Accounts are that Coakley did accompany Gehrig on his first day in pinstripes as a sort of icebreaker, and, according to Robinson, a Columbia contingent served as a cheering squad in the stands while Gehrig took his first batting practice.28

Gehrig had little to do with Columbia after he signed with the Yankees, though he did keep in touch with Coakley and returned to campus on occasion during team practices even after he rose to superstardom.29 Upon Gehrig’s untimely death from the disease that bears his name in 1941, Coakley was an honorary pallbearer at the funeral. He still referred to Gehrig as “my boy.”

Reporters were referring to Columbia baseball as “the Coakleymen” pretty regularly by the 1930s. The team won back-to-back championships in the Eastern Intercollegiate League (EIL), the predecessor to the Ivy League,30 in 1933 and 1934.

Pitcher Ray White was the captain of the 1933 team, winning eight of Columbia’s 13 victories that year, with an ERA below half a run.31 White, first baseman Owen McDowell (the captain of the 1934 team), catcher Ed Brominski (the 1935 captain), and outfielder Al Barabas (1936) all signed professional contracts with minor league teams upon graduation.32 White gained infamy while with Newark when he knocked Lou Gehrig unconscious with a pitch during a June 29, 1934, exhibition game. Gehrig had apparently been less than friendly upon meeting the fellow Columbia baseball alum beforehand, and White took out his rage with a beanball.33

That Coakley had four players in four years sign professional contracts was notable, as he claimed he generally discouraged players from going pro.

“It’s a waste of time for most college players to attempt to make the big league grade. The odds against them are too heavy,” Coakley wrote. “It’s far better for the average college student to enter some other business or profession upon graduation. The greatest satisfaction I have derived from coaching is to meet a boy who has played for me five or ten years after he’s left Columbia and have him tell me I helped him make a success of his job.”34

That being said, Coakley had spotting talent down to a science, as he described to a student reporter in 1947 about his methods for whittling down teams during tryouts:

The first thing I notice about a player is how he throws. To a ball-player, a man must have a good arm. Once I’ve been satisfied as to a man’s throwing ability, I carefully watch his batting form. It’s impossible to determine whether or not a man is a good hitter, but I can tell with just one swing whether a man is not [a] hitter at all. Any batter that stands in the box with his stomach and gut sucked in cannot possibly be a hitter. A man has to stand at the plate with his body relaxed. Any man that possesses a fear of being hit is just not a big leaguer. A ball player should have enough confidence in his own reflexes to not even consider the possibility of being hit by a pitch.35

McCormack remembered Coakley watching him play and suggesting he become a switch hitter. “I did and hit better,” McCormack said.36

“It’s true you can’t do much in the way of making a hitter out of a man who hasn’t some natural ability,” Coakley said. “But you can improve both a good batter and a bad batter.”37

Coakley was open to new ideas. When his team played a handful of practice games against the Royal Giants of Brooklyn in 1922, he allowed trainees from the umpires’ school to call the game.38

In 1938, upon learning of research that a yellow baseball might be more visible than a white one, Coakley suggested that Columbia use it during a regular game. On April 27, the Lions defeated Fordham with the new ball, on a game-winning triple by future college and pro football Hall of Famer Sid Luckman. Of the yellow ball, Coakley said, “One game isn’t enough, but I’m inclined to like it.”39

He also sometimes brought his major league friends in to help coach his players, including Chief Bender, Gabby Street, and Herb Thormahlen. According to McCormack, the Yankees gave Coakley a season pass. Coakley had a little fun with a reporter the year Thormahlen helped out. The reporter was impressed by a particular lefthander warming up on the mound for Columbia and asked who it was. “Does he look good to you?” Coakley said, and the writer complimented his “motions and the assurance with which he carried himself.” Coakley revealed it was ex-major leaguer Thormahlen. “Funny how you can tell a player when you see one even walk on a field.”40

“During our 1937 season, I was listening one day as Andy was talking about Joe DiMaggio (who had come up in 1936),” McCormack recalled. “DiMag greatly impressed him. Andy had been trying to figure out how he would pitch to Joe. At that time he was stumped. Just when he thought he had figured it out DiMag would blast the pitch Andy thought might get him. Whether he ever worked out how to pitch to DiMag, I don’t know.”41

“He always sat at one corner of the dugout,” said Jerry Klingon, who played for Coakley between 1939 and 1942, “the corner closest to home. He had one signal, for a steal. He would cross his legs, and he would wiggle his fingers with his left hand. Everybody in the league knew it, of course.” Perhaps for that reason, Klingon noted, Columbia tried to steal only “once in a blue moon.” The one time Klingon himself received the signal, it resulted in his only steal of the season.42

In 1924 the team had moved 100 blocks north to Baker Field, a more spacious location overlooking the Hudson River. Baker Field was the site of the first televised baseball game. In the second game of a May 17, 1939, doubleheader, four hundred households connected to NBC saw Princeton defeat Columbia, 2-1, in extra innings. Columbia’s captain, Hector Dowd, pitched the entire ten innings; Sid Luckman played shortstop.

“They had one camera, and one guy announced it, with a chair along the third base side. It was Bill Stern doing it for RCA, NBC,” said Klingon, who was on the roster that day.43

“College games are generally decided by pitching, anyway,” Coakley said. “If you have a real pitcher in there, the coach could be in China and the score would be the same.”44

But college baseball, even in the 1930s, still lagged well behind football in terms of popularity. In 1930, Coakley boasted about 2,000 fans turning out to a game between Columbia and Yale. Writer John Kieran pointed out that a football game generally drew around 40,000.45

As early as 1935, Coakley had hatched a plan to bring more fans: a “college world series.” The way he envisioned it, eight American college teams and possibly one from Japan would compete against each other over four days of doubleheaders at Yankee Stadium or the Polo Grounds in early summer, after classes ended. He had already garnered interest from the Big Ten, Big Six, Pacific Coast, Southeastern, Southern, and Southwestern conferences, but the plan fell apart year after year from lack of financing.46

A “College All-Star” game, another precursor to the College World Series, was organized at Fenway Park on June 14, 1946. Coakley was one of three assistant coaches of the East team under head coach Jack Barry from Holy Cross. The East defeated the Midwest all-stars, 6-2.

It would take until 1947, when the NCAA took up the idea independently, before the College World Series as we know it came to fruition.

Perhaps it was just as well; Columbia’s teams around then weren’t among the league’s best. Between 1935 and 1943, the Lions posted just one winning season (1940). Then, they won the EIL championship in 1944, going 11-6-1 (7-1 within the league) behind the strong pitching of lanky righty Dick Ames, who led the league in strikeouts, and Harry Garbett, who also played third base. Both signed with the Yankees organization and played briefly for Newark after college.

During World War II, talent was a mixed bag. The draft board was often calling up players who tried out for the team, so Coakley seized what he could get. Only seven players on the 1943 team returned in 1944.47 Ames had gone to Yale undergrad, but was eligible as a Columbia medical student. Lou D’Errico, the captain in 1944 and 1945, was a dental student. Paul Governali and Bill Swiacki, who both went on to professional football careers, also passed through the Columbia nine in the mid-1940s.

Columbia dropped its first ten straight to start 1950; by 1951, indications were that Coakley was slowing down. Physically drained, he announced in early May that the season would be his last.48 Two days later, Holy Cross hosted a “day” in his honor when the Lions visited Worcester, his alma mater49 presenting him with luggage and a desk set. Columbia finished the year 10-7, the same record as the team during Coakley’s first season 37 years earlier. Overall, Coakley compiled a 315-296-11 record, with three EIL titles (the 1916 squad had been 17-1 before formal league play).

John Balquist, a former player-turned-assistant coach under Coakley, was named his successor.

“I leave college baseball with keen regret,” Coakley told The Sporting News that fall. “I leave it with fond memories, with recollections of great players at Columbia, with a feeling of having torn myself away from something very much a part of my life. However, the calendar shouts that I am nearing 69, after which it will be 70, and it is better that a younger coach pick up the task.”50

In that same interview, Coakley spoke of college baseball being “much maligned,” drawing more than it had years before, but would have to overcome “tremendous financial handicaps” to keep going. Furthermore, he expressed caution against college coaches not to “pattern their kids after the big leaguers, and insist on a double play perfection which the boys simply cannot master.”51

On November 14, one hundred members from previous teams Coakley had coached paid tribute to him at a dinner party at the Columbia Club. Bobby Watt emceed the proceedings, during which Coakley was given a defense bond and a replica of the Lion at Baker Field. Athletics Director Ralph Furey, Paul Governali, Balquist, and George Smith were among those in attendance.

“Keep throwing them high, hard, and on the outside,” read a well-wishing telegram to Coakley at the ceremony. 52

The Collegiate Baseball Hall of Fame recognized Coakley posthumously (he died in 1963), enshrining him in 1969. In 1970, Columbia renamed its baseball diamond Andy Coakley Field; however, significant renovations in 2008 led to its being renamed in honor of Hal Robertson, an alum who funded the project.53 That fall, Coakley was inducted as part of Columbia’s second Athletic Hall of Fame class. Lou Gehrig and Eddie Collins were among the first.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Jo-Anne Carr at the College of the Holy Cross archives; Columbia University for the general use of its library and archives while the author was a student in 2003; Linda Hall at the Williams College archives; Dr. Gerald Klingon and the late John McCormack for sharing their memories of playing for the Columbia baseball team; Norman Macht for sharing his research about the early Athletics; Nancy Miller at the University of Pennsylvania archives; Gabriel Schechter, formerly of the National Baseball Hall of Fame; the late Ray Robinson for his insight into Coakley and Gehrig; and all the other SABR members who offered me help and support.

This article was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

Statistics are courtesy of www.baseball-reference.com and www.retrosheet.org, unless otherwise noted.

Notes

1 “Major League Stars Will Coach Varsity,” Columbia Spectator, February 18, 1914.

2 Sportsman, “Live Tips and Topics,” Boston Daily Globe, March 14, 1914.

3 Sporting Life, December 5, 1914.

4 “Coakley Invents Novel Method of Teaching Base Sliding to Columbia Men.” New Brunswick Times. January 12, 1915.

5 “Pitching Candidates At Columbia Have Drill in Rowing.” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. February 21, 1915.

6 “Columbia Nine Disappointed Its Followers.” New York Tribune. June 6, 1915.

7 “Coakley Lauds Sensational Records of ’16, ’33 Squads.” Columbia Spectator. August 27, 1943.

8 Buonoguro chose a career in medicine instead, and Watt would eventually become Columbia’s athletic director.

9 Spink, J.G.T., “Mack Star, College Coach and Business Man,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1951. Beck nearly lost his eligibility in 1916 when it was discovered he had played — albeit possibly unpaid — in a game with a minor league team on a Sunday. “Perplexing Baseball Problem at Columbia, New Brunswick Times, May 18, 1916.

10 “Coakley in New Contract,” Oelwein Daily Register, December 15, 1916.

11 “Andy Coakley, 81, Ballplayer, Dies.” New York Times. September 28, 1963.

12 “Baseball Season Begins Tomorrow,” Columbia Daily Spectator, March 27, 1917.

13 “Coakley Addresses Baseball Aspirants,” Columbia Daily Spectator, February 28, 1928.

14 Correspondence between John McCormack and the author, March 15, 2008.

15 “Coakley Cancels Baseball Smoker,” Columbia Daily Spectator, March 1, 1921. Gerald Klingon, who played under Coakley from 1939-42, in his interview with the author, was not aware Coakley had any children.

16 “Military Training for Baseball Men,” Columbia Spectator, March 6, 1917. Coakley did not have to register for Selective Service until the draft age limit was expanded from 30 to 45 three months before the war ended in 1918.

17 Columbia would field intramural athletic teams to compete against each other that spring, however.

18 So sealing this sudden about-face by the NCAA was U.S. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker’s suggestion that sports be mandatory on campus, to keep young men in shape for the military. See, e.g., “Athletic Delegates Urge Card System,” Columbia Daily Spectator, August 7, 1917.

19 The move was likely a cost-cutting measure. As a condition of football being restored to Columbia in 1915 after a decade’s ban, the school had mandated its gridiron coach be a permanent member of the Department of Physical Education. See “Dawson, Princeton Football Mentor, to Coach Baseball, Basketball and Gridiron Teams Here Next Season,” Columbia Daily Spectator, April 25, 1918.

20 Editorial, “A Boom for Athletics,” Columbia Daily Spectator, April 25, 1918.

21 One of Coakley’s clients was US Open champion golfer Gene Sarazen. “Gene Insured,” The Circleville (Ohio) Herald, July 7, 1932.

22 Coakley didn’t hesitate to show he could still pitch well enough as a young coach, as evidenced by his shutting out his own players for two innings during a scrimmage in 1918. “Coakley’s Pets in Trim for Maroon,” Columbia Daily Spectator, April 9, 1918.

23 “Coakley Has Won Success On Diamond As Player and Coach,” Columbia Daily Spectator, January 6, 1921.

24 “Coakley is Re-Engaged as Columbia B.B. Coach,” The Bridgeport Telegram, October 26, 1923.

25 Telephone interview with Ray Robinson, July 12, 2017.

26 “Coakley Recalls Lou Gehrig South Field Slugging Days,” Columbia Daily Spectator, August 20, 1943.

27 “Andy Coakley Selects His All-Time Greats,” Columbia Daily Spectator, March 27, 1947. See, for example, Lou Gehrig’s ghostwritten wire column, “Following the Babe” Chapter 6 (printed in the Oakland Tribune, August 23, 1927).

28 Robinson, Ray. Iron Horse: Lou Gehrig in His Time, New York: HarperPerennial, 1991, p. 68.

29 Gehrig returned to Hartford for seasoning under contract with the Yankees in 1923 and 1924. In the latter year, Coakley was hired as head coach for Hartford’s Eastern League opponent, the Pittsfield Hillies. Gehrig went 6-for-11 with two home runs during a three-game set against his former coach on August 13-14.

30 Formed in 1930, the EIL was originally comprised of Columbia, Yale, Princeton, Cornell, Penn, and Dartmouth. Harvard joined in 1934, and Brown, Army, and Navy in 1948. The EIL remained a collegiate baseball mainstay until 1992, when the Ivy League (1954) which had previously functioned only informally as a college baseball league, absorbed the eight teams that weren’t Army and Navy.

31 “Ray White Signs with Yankees; To Be Sent to Binghamton Club,” Columbia Daily Spectator, June 6, 1933.

32 Barabas, who also played football professionally, McDowell, and Brominski were three of the major players in Columbia’s 1934 Rose Bowl championship.

33 Robinson, Ray, “A Misunderstanding, a Beaning, and a Piece of the Gehrig Puzzle,” New York Times, Aug. 28, 2010 (https://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/29/sports/baseball/29gehrig.html).

34 Coakley, Andy. “Hugh Bradley Says: Veteran Coach Says Leagues Helped to Build Up Following,” New York Evening Post, May 12, 1936. Unclear whether these were Coakley’s words or those of a ghostwriter.

35 Berman, Fred, “Andy Coakley, ‘Lion’s Mr. Baseball’ — Part 3,” Columbia Daily Spectator, March 28, 1947.

36 Correspondence between John McCormack and the author, March 15, 2008.

37 Perry, Lawrence, “From the Field of Sports,” The Evening Post: New York, May 9, 1916.

38 “Coakley Tries New Arbiters Daily from Umpires’ School,” New York Times, April 2, 1922.

39 Morris, Peter. A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations that Shaped Baseball, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010 ed., p. 279.

40 Kelley, Robert F., “The Amateur Sportsman,” New York Evening Post, March 23, 1925.

41 Correspondence between John McCormack and the author, May 1, 2008.

42 Telephone interview with Dr. Gerald H. Klingon, 2011.

43 Klingon.

44 Kieran, John. “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, April 12, 1930.

45 Kieran, John. “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, April 12, 1930.

46 “College Baseball Series Suggested,” Ironwood Daily Globe (Mich.), April 3, 1935 (Associated Press report); “Time Out,” The Daily Princetonian, April 26, 1937; “College World Series,” Hartford Courant, June 20, 1937; Kelly, Jack, “Time Out: On College Baseball Game Thrives Coakley Suggests Tourney,” Utica Daily Press, May 6, 1941. In the last article, Coakley cited how the national collegiate championship put basketball on the map in 1939.

47 Schemer, Stewart H., “On the Sidelines: 28,081 Days Ago,” Columbia Daily Spectator, April 14, 1944.

48 Freyberg, Mike. “Coakley to Retire,” Columbia Daily Spectator, May 3, 1951.

49 Coakley had pitched for Holy Cross in 1901 and 1902, before the start of his professional career with the Philadelphia Athletics. Stripped of his collegiate eligibility, he remained enrolled as a student until 1904, but didn’t graduate.

50 Spink, J.G.T., “Mack Star, College Coach and Business Man,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1951.

51 ISpink

52 “Tribute to Coakley,” Columbia Alumni News, December 1951.

53 Another generous donation by alum Philip Satow a few years later added an additional moniker to Andy Coakley’s former namesake: “Robertson Field at Satow Stadium.”