Ball Four

This article was written by Mark Armour

Nearly a half-century after its publication, one does not encounter much negative criticism of Ball Four, Jim Bouton’s 1970 journal mainly recounting his previous season pitching in the major leagues. A best-seller at the time of its publication, the book fundamentally changed sports literature and journalism, and the way we view our sports heroes. In 1995 the New York Public Library honored Ball Four as one of the greatest books published in the preceding century, alongside such works as Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat.

Nearly a half-century after its publication, one does not encounter much negative criticism of Ball Four, Jim Bouton’s 1970 journal mainly recounting his previous season pitching in the major leagues. A best-seller at the time of its publication, the book fundamentally changed sports literature and journalism, and the way we view our sports heroes. In 1995 the New York Public Library honored Ball Four as one of the greatest books published in the preceding century, alongside such works as Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat.

Today’s fans and writers, children or young adults when they first devoured the book, re-read it every two or three years. The book is universally viewed as well-written, provocative, thought-provoking, and funny. It is difficult to imagine that such a book could be controversial, that its author would be shunned by people within the game for many years, and in fact is still shunned. It is so.

After decades of first-person sports books mainly written for high school boys, the first honest adult portrayal of the life of a baseball player appeared in 1960. The Long Season, pitcher Jim Brosnan’s look at his 1959 season in the National League, and his 1962 follow-up Pennant Race, were well received outside the game, and remain classics in sports literature. The great Jimmy Cannon called The Long Season “the greatest baseball book ever written.” Red Smith, in the New York Herald Tribune, called it “a cocky book, caustic and candid and, in a way, courageous, for Brosnan calls him like he sees them, doesn’t hesitate to name names, and employs ridicule like a stiletto.”

In one of the more controversial passages, Brosnan recalls the night two of his Cardinal teammates spent in a bath house (essentially a brothel) on the team’s off-season trip to Japan. The book’s publisher, Harper, required that Brosnan’s original version be modified in deference to the two players, bachelors Joe Cunningham and Don Blasingame. As rewritten, the men partook in “a strenuous exercise or two.” According to Brosnan, the rest of The Long Season appeared essentially as he wrote it.

Rather than the typical ghosted autobiographies baseball had been serving up for years, with scrappy determination mixed liberally with inspiration from God, family and country, Brosnan showed us real men—men who drank, chased women, argued over trivialities in the bullpen, worried about their mortgages and their families and their futures. Brosnan wanted to pitch well, especially to make more money, but there were many days that he would have just as soon called in sick and stayed home with his family. He also liked a martini or two after a hard earned victory, or, for that matter, after a defeat. In other words, he had a lot in common with the rest of us, the people reading his book. Brosnan does not employ profanity, and, other than the single scene described above, does not reveal sexual encounters.

Inside the game, The Long Season caused an uproar. Brosnan minced no words about several people, including his former manager Solly Hemus and Cardinal broadcaster Harry Caray (“an old blabbermouth”). Hemus was not amused: “You think Brosnan’s writing is funny, wait until you see him pitch.” Joe Garagiola called him a “kookie beatnik,” complaining: “that stuff about him calling home to see if there were enough olives for martini hour. What kind of stuff is that to write about. How is that going to look to the kids?”

One person who loved the book was Jim Bouton, a 21-year-old pitcher for the Yankees’ Greensboro, North Carolina, farm club. “I really enjoyed it tremendously,” he later recalled. “I remember when I was reading the book, the parts that excited me the most were whenever he would quote any of the players or coaches … It was fascinating to me what the ballplayers actually said to each other during games, in the bullpens, or after games. It really revealed them as personalities. What were these guys like? How did they think? What do they talk about? What’s going on in their heads, you know?”

After Brosnan, realistic inside looks at the world of sports began to appear occasionally, though, as most insiders could not write like Brosnan, the books required a collaborator. Bill Veeck, a former club owner, teamed up with Ed Linn on Veeck as in Wreck (1962) and The Hustler’s Handbook (1965), revealing Veeck’s frustrations in years of dealing with his fellow owners and commissioners. Bill Veeck was a man of many talents, but self-preservation was not one of them—his former colleagues blocked his attempts at buying another team until 1975. Jerry Kramer’s Instant Replay, written with Dick Schaap in 1967, was a best-selling look at life with pro football’s Green Bay Packers. More typically, Joe Namath and Schaap’s I Can’t Wait Until Tomorrow (‘Cause I Get Better Looking Every Day) was about what you’d expect: salacious details of Joe’s off-the-field adventures, with an occasional dose of football thrown in.

Sports reporting also evolved rapidly in the 1960s. Jimmy Cannon, the most admired sportswriter of his generation, had for many years written memorable prose celebrating the heroes of the era, men like Joe DiMaggio (who “stirred the dreams of countless boys”) and Joe Louis (“a credit to his race—the human race”). But many of the men who arrived in the press boxes in the 1950s thought of themselves not merely as writers, but as reporters, as men looking for a story. The new breed was down in the clubhouse asking the players and manager not just what they did, but “why?” Why did you throw that pitch, why did you try to steal that base, why did you take out the pitcher?

Cannon in particular was contemptuous of this trend, referring to one particularly aggressive group of reporters as “chipmunks.” Cannon later complained to Jerome Holtzman: “The chipmunks love the big-word guys, the guys with the small batting averages but … big vocabularies.” Although Cannon used the term derisively, the “chipmunks” considered it a badge of honor, and other writers began to claim the nickname for themselves.

Cannon’s original targets included Leonard Shecter (New York Post), Stan Isaacs (Newsday) and Larry Merchant (Philadelphia News). As they saw it, their crimes were their lack of deference to the New York Yankees, and their admiration for the new outspoken breed of athletes, most especially Muhammad Ali. These men (and yes, they were all men) covered sports the way they would have covered politics or a fire, looking not just for news, but for an interesting angle. Inevitably, the atmosphere in locker rooms grew tense.

Lenny Shecter was typical of the type, a skeptic about what he heard in locker rooms, an early supporter of Ali, but the author of a harsh Esquire piece on the widely revered Vince Lombardi. In 1968 Shecter wrote a powerful article for Life magazine, Baseball: The Great American Myth. The story follows the Boston Red Sox, who had won a celebrated pennant the previous year but were going through a less newsworthy, injury-filled season, ultimately finishing fourth in a ten-team league. Shecter revealed players frustrated with their performance, worried about their futures, angry with manager Dick Williams, and bored of the drudgery of the road. There were no heroes or glamour in Shecter’s piece.

The following year Shecter wrote The Jocks, a humorous but cynical broadside that laid waste to much of the sports establishment, including fellow newspapermen (pawns of the teams they covered), television (wielding too much power), the NCAA, all major professional sports, and many of our biggest sports heroes, men like Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris. A fascinating and funny read, it was not all negative. He devoted an entire chapter to Casey Stengel, who he had covered with the early Mets and whom he loved, and another chapter to people he calls “losers”, athletes who were too bright and thoughtful to fit into the hypocritical sports world. One of these losers was Jim Bouton, a Yankee pitcher Shecter admired.

When Bouton joined the Yankees in 1962, he was warned by his teammates about associating with reporters, especially Shecter, or “that f**king Shecter.” Bouton rarely did what he was told, so he not only talked with the reporters, he became friends with many of them, including Shecter. Bouton had early success with the Yankees, winning 41 games in the 1963 and 1964 seasons, and winning two of his three World Series starts (losing his other one, 1-0).

Shecter wrote a glowing piece on Bouton for Sport in 1964, revealing the pitcher’s sense of humor, his broad set of interests, and his artwork, while dismissing Bouton’s reputation as an oddball: “He stands out because he is a decent young man in a game which does not recognize decency as valuable.” A few years later, when Shecter had left the Post and Bouton was struggling to hang on with the Yankees, Shecter published a story about Bouton and his wife’s adoption of a Korean child. Bouton and Shecter were kindred spirits, bright men who loved the game, rankled at the hypocrisy, and took pleasure in tweaking the stuffed-shirts who ran the business.

After the success of Kramer’s Instant Replay, Shecter, now freelancing, wondered if the time was ripe for an honest baseball diary—a day-to-day inside look at the world of baseball. He approached Bouton during the winter of 1968, and was told, “Funny you should mention that. I’ve been keeping notes.” Thus joined, their common purpose, as later recounted by Shecter, was “to illuminate the game as it never had been before.” The illumination was to include daily frustrations, meanness, and “extraordinary fun.”

There was little reason to suppose that such a venture would be successful. For one thing, in 1968 Bouton had pitched, and not particularly well, for the Seattle Angels of the Pacific Coast League, and in 1969 was merely invited to spring training by the Seattle Pilots, an expansion major league team. There was no guarantee that he would make the club, or stick with them long. When Jerry Kramer wrote Instant Replay, he was a star player on the best team in football. Bouton, if he made it, would be a mediocre pitcher on a bad team. If he made it.

There was little reason to suppose that such a venture would be successful. For one thing, in 1968 Bouton had pitched, and not particularly well, for the Seattle Angels of the Pacific Coast League, and in 1969 was merely invited to spring training by the Seattle Pilots, an expansion major league team. There was no guarantee that he would make the club, or stick with them long. When Jerry Kramer wrote Instant Replay, he was a star player on the best team in football. Bouton, if he made it, would be a mediocre pitcher on a bad team. If he made it.

As it happened, Bouton made the Pilots in the spring and stayed in the major leagues most of the season. He was sent down to Triple-A Vancouver briefly, and in August was traded to the Houston Astros. Overall he pitched in 81 games, almost all of them in relief, and finished the season in a National League pennant race. Given where he started in March, it must be considered a wildly successful season.

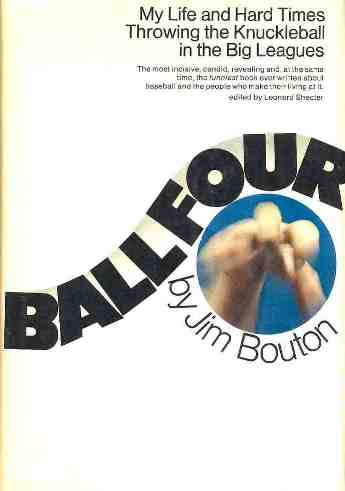

More importantly for his place in history, Bouton spoke into a tape recorder almost every day all season and sent the tapes to Shecter, who had the transcripts typed up and turned into a 1,500-page manuscript. The collaborators spent several months haggling over every word to get it down to 520 manuscript pages, or about 400 in the book. After a few rejections, World agreed to put out the book, to be entitled Ball Four—My Life and Hard Times Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues, in the spring of 1970.

Another baseball diary beat Ball Four to the store shelves by several weeks. Detroit catcher Bill Freehan, with the assistance of writers Steve Gelman and Dick Schaap, penned Behind the Mask (World), a journal of his 1969 season with the Tigers. Freehan’s book caused a stir for its candid look at some of the goings on in the Detroit clubhouse, most notably Freehan’s claim that the Tigers allowed star pitcher Denny McLain to flout team rules. As luck would have it, by the time excerpts from the book appeared in Sports Illustrated in March, McLain was being investigated by baseball for conspiring to operate a sports book, for which he would be suspended for half the 1970 season. Freehan was embarrassed by the contents of the book, apologized to his team, and more or less refused to talk about it ever again.

Early in the season Bouton had asked Jim Owens, his Astros pitching coach and a man Bouton admired, whether there would be fallout if the team didn’t like the book. Owens responded: “Depends on how you’re doing at the time.” Bouton was not doing well. He began the season in the rotation, was hit hard in a handful of starts, was relegated to the bullpen, and never got on track the entire season, finishing 4-6 with a 5.40 ERA.

Excerpts of Ball Four first appeared in the June 2 and June 16 issues of Look, the former hitting the streets in mid-May. The selected passages in the first issue included details of Bouton’s contract negotiations with the Yankees, a depiction of many players as ingenious peeping toms, salacious dialog that included sexual humor about players’ wives, the widespread use of amphetamines in the game, and playful kissing between inebriated Seattle Pilots on the team plane. Most of the passages were benignly funny, and included Bouton’s poignant insecurities about his place on his teams (on and off the field).

Although Bouton spent the majority of the book dealing with his day-to-day 1969 life with the Pilots and Astros, his comments on his years with the Yankees predictably generated the most controversy. Bouton described pitcher Whitey Ford’s late-career chicanery, including illegally defacing the baseball. Mickey Mantle came off as a good-natured teammate who occasionally mistreated fans, and who might have had a better career had he spent more time working out to recover from his injuries and less time drinking and carousing with his buddies. Most of his ex-Yankee teammates were particularly unsettled by Bouton’s comments about Mantle. Mickey’s reaction was more ironic: “Jim who?”

Soon after the first excerpts came out in Look, the Astros came into New York to play a four game series with the Mets (May 29-31). The New York press and fans were ready for Bouton, no one more so than Dick Young.

Young was the dean of New York sportswriters, a veteran of three decades with the Daily News, the beat writer for the Brooklyn Dodgers during their glory days, a smart, tireless reporter. No fan of the modern athlete, Young was a vocal critic of Ali, unions, and players expressing concerns for the world around them. As a high-handed moralist, he made a lot of enemies during his long career. In his May 28 column, Young set his sights on Ball Four: “I feel sorry for Jim Bouton. He is a social leper. He didn’t catch it, he developed it. His collaborator on the book, Leonard Shecter, is a social leper. People like this, embittered people, sit down in their time of deepest rejection and write. They write, oh, hell, everybody stinks, everybody but me, and it makes them feel better.”

In Young’s view, Bouton and Shecter used the book as revenge against the people who had rejected them. Bouton had written candidly of feeling out of place in the game: “I know about lonely summers. In my last years with the Yankees, I had a few of them. You stood around in a hotel lobby talking with guys at dinnertime, and they drift away, and some other guys come along, and they drift away, and soon they are gone. So you eat alone.” Young saw the book as Bouton’s chance to get even. Although he admires some of the book (“there are some beautiful passages”), he can not forgive what he sees as petty cruelty and his disrespect for the game. To Young’s displeasure, Bouton came across as being somewhat disinterested, even bored, with the game unless he was pitching in it.

Bouton’s first appearance in New York was on May 31 against the Mets, when he allowed three hits and three runs in one-third of an inning. He was booed from the time he began walking in from the bullpen until he retreated into the dugout after his appearance. He later wrote that it was his lowest moment ever on a baseball field.

The next day, Bouton met with commissioner Bowie Kuhn in Kuhn’s Manhattan office, along with Marvin Miller, the head of the player’s union, and Miller’s aide Dick Moss. Kuhn told Bouton he was disappointed and shocked by the excerpts he had read, so much so that he felt compelled to remove the magazines from his house lest his sons read them. He was particularly discomforted with reports of drug use, sexual verbal jousting amongst the players, and especially the playful kissing game on Seattle’s team plane. Bouton responded that all of it was true, and that no harm would come from his revealing it.

Mainly, Kuhn brought Bouton in to get him to apologize, as Freehan had done earlier that spring, but Bouton did not give an inch. Failing that, Kuhn and Miller spent two and a half hours arguing over a suitable press release. What was finally agreed to was short and non-informative: “I advised Mr. Bouton of my displeasure with these writings and have warned him against future writings of this character. Under all the circumstances, I have concluded that no other action was necessary.” After this brief statement was read, Bouton was asked if he regretted writing the book. “Absolutely not,” responded the pitcher-author.

All this reaction predated the release of the book by several weeks. The Look selections included most of the salacious content of the book, and read in isolation teammates and writers naturally wondered what other bombshells were coming. Reading them today, the excerpts miss the heart of the book, Bouton’s depiction of the day-to-day life of a ballplayer.

Ball Four’s long-awaited release on June 21 brought mainly positive reviews from the nation’s most respected book critics and columnists. As Robert Lipsyte wrote in the New York Times, reading the entire book provides the necessary context for the more revelatory passages, which appear as “a natural outgrowth of a game in which 25 young, insecure, undereducated men of narrow skills keep circling the country to play before fans who do not understand their problems or their work, and who use them as symbols for their own fantasies.”

Within its four hundred pages, the locker room hijinks, the late nights, the occasional resentment of the fans by the players, the petty rivalries, all seem perfectly natural to anyone who had spent time in the army or a high school locker room. The book struck a chord with so many people, perhaps, because while readers could not relate to throwing a 90-mile-per-hour fastball or hitting a slider, they understood too well the frustrations of daily life, spending time in close quarters with people with whom you had nothing in common, and dealing with arbitrary and petty regulations set down by unimaginative bosses.

Christopher Lehmann-Haupt reviewed the book for the Times, and wrote that it renewed his long dormant interest in the game. Rex Lardner Jr., in The New York Times Book Review, called it the “frankest book yet about the species ballplayer satyriaticus,” concluding, “I hope he makes a million bucks.” It was hailed by the Washington Post (David Markham) “a wry, understated, honest and memorable piece of Americana, by a good man they will clobber because of it”; and the Los Angeles Times (John Gregory Dunne): “an uncomfortably accurate look at life in the big leagues”).

In the New Yorker, Roger Angell praised Bouton as a “day-to-day observer, hard thinker, angry victim, and unabashed lover” of the game, and lauded the book’s portrayal of “his own survival as a human being caught up in an exhausting and ultimately unforgiving business.” As a deeply respected chronicler of the game, it is telling that Angell was not in the least surprised or overly troubled by Bouton’s more unsavory revelations. Instead, Angell saw “a rare view of a highly complex public profession seen from the innermost inside, along with an even more rewarding inside view of an ironic and courageous mind. And, very likely, the funniest book of the year.”

David Halberstam won a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the Vietnam War for the New York Times, but had yet to establish his eventual association with baseball. Writing for Harper’s Magazine, he called Ball Four the “best sports book in years, a book deep in the American vein. … It is a fine and funny book, with rare intelligence, wit, joy, and warmth; and a comparable insider’s book about, say, the Congress of the United States, the Ford Motor Company, or the Joint Chiefs of Staff would be equally welcome.” Halberstam believes he understands the resentment of the beat writers, the mythologizers and hero-makers—once “outflanked”, they must attack the intentions of the writer. Thus, Bouton became a “social leper, and thus Sy Hersh, when he broke the My Lai story, became a ‘peddler’ to some of Washington’s famous journalists.”

His fellow players still did not like it. Joe Morgan, his teammate on the Astros, said, “I always thought he was a teammate, not an author. I told him some things I would never tell a sportswriter.” By the time the book came out, the Seattle Pilots were extinct, having relocated to Milwaukee as the Brewers. Many of his ex-Pilot teammates, including Fred Talbot, Wayne Comer, and Don Mincher deeply resented the book and Bouton. Jerry McNertney wasn’t troubled by the book, and Gene Brabender, while not condoning it, did allow that it was “hilarious”.

Jimmy Cannon was not amused. He blamed Shecter, though he never mentioned the collaborator by name in his scathing July 28 column. “The book is ugly with the small atrocities of the chipmunk’s cruelty. In a way, Bouton is a chipmunk, a man who obviously cherishes himself as a social philosopher. The influence of the ghost is obvious … The literary critics take him seriously. It is as though he were assaulted with a sudden inspiration and rushed to a typewriter and put it all down in a flurry of creation. But he went to the spook, and one has to speculate where Bouton stops, and the ghost begins. Whose hatreds are these, whose theories? Which ones ethics governed the partnership?”

The diverse reaction to the book was part of the social and political divide the country was going through. Bouton, a “communist” to some of his critics, unabashedly supported the war protesters, and held decidedly liberal views on civil rights, religion, the rights of women, the new player’s union, poverty, and the other divisive issues of the time. What’s more, he confidently stated his opinions in his book. Not surprisingly, the liberal press was more likely to praise it. George Frazier, a Boston Globe columnist who later showed up on Richard Nixon’s enemies list, called Ball Four “a revolutionary manifesto.” In his strident and angry review, Frazier challenges the books critics: “What is happening among baseball players, their doubting the divinity of demagogues … is what is happening among housewives and their husbands who have had their fill of the shoddy wares and planned obsolescence foisted on them by American industry. Bouton is now being slandered by baseball’s benevolent old men and their lackeys. Who the hell does Bowie Kuhn think he is?”

The most considered of Ball Four’s negative reviews was written for Esquire by Roger Kahn, a freelance writer still two years away from the publication of his masterpiece, The Boys of Summer. Kahn admired Shecter and Bouton, but is particularly critical of their depiction of life on the road, especially when Bouton and Shecter name names. One member of the club is quoted: “Boys, I had all the ingredients for a great piece of ass last night—plenty of time, and a hard-on. All I lacked was a broad.” To Kahn, the naming of this player, and the naming of a few other players in other passages, is a terrible “intrusion” on the player and his family.

Bouton defended himself against this type of criticism, responding that he portrays himself as a part of the off-field stories, the drinking, the beaver shooting, and all the missed curfews. This is true, but Kahn correctly counters that Bouton did not show himself cheating on his wife, an act which carried, and still carries, an additional level of opprobrium from friends and family. Bouton’s wife Bobbie is shown to be a loving supporter of her husband’s career, laughing at all the rollicking good fun the players engaged in. Years later, after their divorce, the former Mrs. Bouton wrote that she naively trusted that her husband was different from the typical philandering ballplayer depicted in his book, and was crushed to later discover that he was not. (Kahn’s view on issues of decorum evolved over the years. In his 1987 book Joe and Marilyn, for one example, he claims to reveal details of their private body parts, and discusses the quality of their love-making.)

Kahn’s other serious concern with Ball Four is that Bouton and Shecter deceive the reader by suggesting that Bouton could still pitch. To Kahn, the book would have been better had Bouton written about his anxieties over the ending of his career, rather than continually blaming others for not pitching more. In fact, Bouton was leading the Pilots in games pitched (57) at the time he was traded, and his 73 games on the season were the fifth highest total in the major leagues. What Bouton really wanted was a chance to start, or to pitch in tighter situations, and his statistics were actually significantly better than all of the teams’ starting pitchers that season.

What Kahn missed, it seems, is that the book is overflowing with self-doubt. The Jim Bouton of 1969 desperately wanted more of a chance, because he loved the game and the competition, but he does not come across as someone who has an outsized view of his abilities. The reader can understand a bad team’s reluctance to invest a lot of innings in a 30-year-old knuckleballer coming off several bad seasons, but it is not realistic to expect that perspective from the pitcher himself. He wanted to pitch more, and he wanted his managers and coaches to let him pitch more. Why would he not?

After being sent to the minor leagues in July 1970, in the midst of the controversy over his book, Bouton soon decided to retire from the game. Although he never used the publicity surrounding Ball Four as an excuse, it is not hard to imagine the strain this summer must have had on a mediocre pitcher trying to master a strange pitch. Bouton never lost his love for the competition. After a few years pitching semi-pro ball while working in television in New York, he made two tries at a comeback in the minor leagues, the second of which culminated in a few starts for the Atlanta Braves in 1978. He was still pitching semi-pro baseball at age 60.

Ball Four sold 200,000 copies in hardcover, and countless more in paperback. It has been reissued three times, once every ten years, with epilogues updating Bouton’s life and the lives of some of his teammates and friends from the pages of his book. In 1971 Bouton and Shecter collaborated on a sequel, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, discussing the circus surrounding the publication of Ball Four. Bouton dedicated the new book to Dick Young and Bowie Kuhn.

Sources

The primary sources for this article are mentioned within. Bouton’s I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally tells the story of Ball Four from the author’s perspective. The excerpts in Look are especially helpful, as are all of the reviews of the book that came out in 1970. I interviewed Bouton for this story in 2005. It originally appeared in SABR’s 2006 convention journal Rain Check: Baseball in the Pacific Northwest.