Bill Veeck

Bill Veeck’s one-man carnival came blaring into Chicago on March 10, 1959. He and an investor group bought a majority interest in the Chicago White Sox from Dorothy Comiskey Rigney, granddaughter of the franchise’s founder, Charles Comiskey.

Bill Veeck’s one-man carnival came blaring into Chicago on March 10, 1959. He and an investor group bought a majority interest in the Chicago White Sox from Dorothy Comiskey Rigney, granddaughter of the franchise’s founder, Charles Comiskey.

The 45-year-old Veeck was coming home. He liked to say, “I am the only human being ever raised in a ballpark.”1 The ballpark was Wrigley Field, where his father was president of the Cubs.

Veeck’s road to Comiskey Park wound through Cleveland, where he set attendance records and won a World Series; and St. Louis, where he lost his sports shirt trying to save the Browns. Fellow owners ran him out of the game, but they could not stop him from having fun along the way.

Bill Veeck lived a joyously public life and wrote his own legend. Sometimes it is hard to know where the life stops and the legend begins.

William Louis Veeck Jr. was born in Chicago on February 9, 1914, to William L. Veeck Sr. and Grace Greenwood DeForest Veeck. His father was a sportswriter under the pen name Bill Bailey. After Veeck criticized the Cubs in his columns, owner William Wrigley dared him to take over the team and prove he could do better. Veeck did so in 1918, and built pennant winners in 1929, 1932, and 1935.

Young Bill began hanging around the ballpark at the age of 10, working as a vendor and ticket seller. The boy was sent to the exclusive Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, but lasted only a few weeks. After two years in a public high school in the Chicago suburb of Hinsdale, he was dispatched to the Ranch School in Los Alamos, New Mexico, whose experimental curriculum followed the back-to-nature philosophy of Henry David Thoreau. Bill left without graduating.

He passed an entrance exam at Kenyon College in Ohio. He remembered his brief college career as a nonstop party, but he was elected freshman class president, played football and basketball, and joined the Beta Theta Phi fraternity. He quit in his second year when his father was diagnosed with leukemia. In the last weeks of his life, William Veeck could not digest anything but wine. Prohibition was on, so, his son said, he procured a supply from Al Capone. The father died in 1933, when Bill was 19. Veeck Jr. always referred to his father simply as Daddy, and revered him, but the two could not have been less alike. William Veeck was a starchy, formal gentleman, the perfect picture of establishment dignity. Junior famously never wore a necktie, had wild, kinky, reddish hair that won him the nickname Burrhead, and spent his life tilting at every establishment windmill in sight.

Veeck took an $18-a-week job with the Cubs, who were now owned by William Wrigley’s son, Philip K. Like Veeck, P.K. Wrigley was an apple who fell far from the tree. His father was a supersalesman; Philip was painfully shy, happier when tinkering with a car or some other machinery than meeting the public. Young Veeck was brimming with promotional ideas, such as installing lights at the ballpark. Young Wrigley rejected all of them. Veeck’s only contribution to the Cubs was planting the ivy on Wrigley Field’s outfield walls, but that was Philip Wrigley’s idea.

Veeck married Eleanor Raymond on December 18, 1935. She had been an elephant wrangler and horseback rider with the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Bill said her daredeviltry appealed to him, but Eleanor maintained that he exaggerated her feats with the circus.

At 27 Veeck bought his first ballclub, the Milwaukee Brewers of the Double-A American Association, then the highest level of the minors. He sometimes said he paid nothing for the failing franchise while assuming $100,000 in debts, but the Brewers’ business manager, Rudie Schaffer, said Veeck put up $40,000. It was mostly other people’s money, as it would always be when Veeck bought a team.

The 1941 Brewers were in last place when he took over, bringing along one of his investors, Charlie Grimm, as manager. Grimm, who played first base and the banjo left-handed, had managed the Cubs’ 1935 pennant winner. Jolly Cholly was a perfect fit for Veeck.

Milwaukee became Veeck’s tryout camp, where he auditioned his promotional schemes. He took the successful ones with him to the majors. He cleaned and painted the Brewers’ dilapidated park. He gave away prizes almost every night, showing a fascination for animals: live lobsters, pigeons, chickens, guinea pigs, and a particular favorite, a swaybacked horse. Most of the promotions were not announced in advance; he wanted fans to come to the games anticipating a surprise. He scheduled morning games for overnight workers at war plants, and served a breakfast of cornflakes to all comers. He believed a trip to the ballpark should be fun. But he also built a winning team. Veeck bought players, spending money he did not have, and sold them to raise capital for more purchases. The Brewers nearly won the American Association pennant in 1942, his first full season, then won the next three in a row.

Veeck later wrote that he tried to buy the bankrupt Philadelphia Phillies after the 1942 season, and intended to stock the team with black players, breaking organized baseball’s color line three years before Jackie Robinson signed with the Dodgers. In his 1962 autobiography he asserted that he had lined up financing and enlisted the promoter Abe Saperstein, owner of the Harlem Globetrotters, to help sign Negro Leagues stars. Veeck said he informed Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis of his plan as a courtesy, but that Landis and National League president Ford Frick thwarted him by arranging a quick sale of the Phillies to another buyer.

Most histories of baseball integration have repeated the story. It fit Veeck’s carefully burnished image as the bane of authority. But in 1998 David M. Jordan, Larry R. Gerlach, and John P. Rossi declared, “[I]t is not true.”2 Although Veeck claimed his bid was “known all over the baseball world,” later researchers have found only a handful of references to it before Veeck’s autobiography, most of them based on Veeck’s statements. When Veeck signed the second black major leaguer, Larry Doby, in 1947, he did not mention that he had tried to integrate baseball five years earlier. However, the historian Jules Tygiel noted that is impossible to prove a negative, and concluded that Jordan, Gerlach, and Rossi may have been too quick with their “blanket dismissal of Veeck’s assertions.”3

In any event, Veeck was not around to celebrate the Brewers’ pennants. He joined the Marines after the 1943 season. The next spring he was stationed on the Pacific island of Bougainville when the recoil of an anti-aircraft gun smashed his right leg. He spent the rest of the war in hospitals.

Grimm left the Brewers for another tour as manager of the Cubs in 1944, and persuaded his old friend Casey Stengel to take over in Milwaukee. Stengel had been fired after losing records as manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers and Boston Braves. Veeck was furious when the news reached him in the Pacific weeks later. He wrote Grimm a blistering letter, demanding that he fire that clown Stengel forthwith. After Stengel brought home the pennant, Veeck admitted his mistake. He asked Stengel to stay for 1945, but Casey had heard about the letter and went home to California.

Veeck sold the Brewers soon after he returned from military service in 1945. “It was a choice between the club and my marriage,” he wrote later.4 The marriage had been in trouble even before Veeck joined the Marines. He moved Eleanor and their three children to a dude ranch in Arizona that he named The Lazy Vee.

His reconciliation with his wife didn’t take. Neither did his divorce from baseball. Within a few months he began looking for a way to get back into action, “a vulture in search of a dying ball club.” The Cleveland Indians had not won a pennant since 1920, and had seldom been in the race. Veeck put together a syndicate to buy the team for $2.2 million. He devised what he called a debenture-stock group, which allowed his backers to leverage their investment by paying only a small amount for stock and putting the majority of their money in the form of a loan to the team (the debenture), then leverage it again by borrowing most of the purchase price. He put up just $268,000 in cash for a 30 percent share of the club.

Veeck brought his stunts, fireworks, and giveaways with him. Although other minor-league owners had embraced the value of promotion, such folderol had never befouled a big-league park. New York Yankees public relations director Red Patterson summed up the state of the majors’ marketing efforts. He said Yankees general manager George Weiss vetoed a cap giveaway with the disdainful remark, “I don’t want every kid in New York walking around in a Yankee cap.”5

Responding to sneers that his stunts were decidedly lowbrow, Veeck said, “My tastes, I have found, are so average that anything that appeals strongly to me is probably going to appeal to most of the customers.”6 In his philosophy, “every day was Mardi Gras and every fan a king.”7 And a queen: he gave away nylon stockings, which were hard to get soon after the war, and thousands of orchids. After he took over in June 1946, Veeck pushed the Indians’ lagging attendance above 1 million for the first time. He moved the games from League Park, which had room for only 22,500 people, to Municipal Stadium, with a capacity of 78,000. (The team had previously used the bigger park only on Sundays, holidays, and for games when a large crowd was anticipated.) He removed the door to his office and listed his home phone number in the public directory.

Veeck tried again to patch up his marriage during the 1946 World Series. He invited Eleanor to join him at the Series — unfortunately, along with dozens of friends and business associates. Veeck spent his time entertaining his guests rather than his wife. The Series lasted seven games. Eleanor did not. She left him for good.

After the Series, Veeck’s right leg was amputated below the knee. When his new artificial leg arrived, he threw a party to celebrate. He later endured successive amputations as infections traveled up the stump of his leg, 36 operations in all.

The Indians finished sixth in 1946 and rose only to fourth the next year, although attendance jumped to 1.5 million, second best in the league. Veeck signed the AL’s first black player, Doby, in July. The next year he signed Negro Leagues legend Satchel Paige, played up the mystery surrounding Paige’s age, and had a new drawing card as well as a useful pitcher.

Veeck also acquired Yankee second baseman Joe Gordon, a former MVP who returned to stardom with Cleveland for a few years, but he had to give up pitcher Allie Reynolds, who became a key man on New York’s five straight World Series winners. Finally, he decided to get rid of his shortstop and manager, Lou Boudreau. At 30, Boudreau was a former batting champion and seven-time All-Star, but Veeck derided him as a “hunch” manager.

When word of the plan to trade Boudreau leaked, Veeck faced a hurricane of criticism. There was no sports-talk radio then, but fans made their opinions clear in letters to the papers, and sportswriters lent a megaphone to the outcry. Veeck tried to turn a public-relations disaster into a coup. He announced he would bow to the fans’ wishes and keep the manager.

The Boudreau trade was the best deal Veeck never made. Boudreau had the season of his life in 1948, batting .355 with a .453 on-base percentage and a .534 slugging average, and winning the MVP award. Veteran third baseman Ken Keltner turned in a career year, Gordon slugged 32 home runs, and unheralded pitchers Gene Bearden and Bob Lemon each won 20 games while finishing 1-2 in ERA. The Indians fought the Yankees, Red Sox, and the surprising Philadelphia Athletics in a tight pennant race. With a winning team and a thrilling race added to Veeck’s nonstop promotions, 2.6 million fans turned out, a major-league record that stood for 14 years. The season ended with Cleveland and Boston tied. In a one-game playoff, Boudreau hit two home runs as the Indians won, 8-3.

Veeck made the World Series an event for the common fan. Series tickets had always been sold in sets for all home games (the middle three were played in Cleveland), but Veeck sold single-game tickets to allow three times as many people to see their team play for the championship. The Indians defeated the Boston Braves in six games.

That 1948 season was the triumph of Veeck’s life. After the victory parade, he went home to his empty apartment. He wrote later, “I had never been more lonely in my life.”8

That 1948 season was the triumph of Veeck’s life. After the victory parade, he went home to his empty apartment. He wrote later, “I had never been more lonely in my life.”8

That may explain why Veeck’s years in Cleveland were marked by a desperate quest for excitement. He joined a group of late-night revelers known in the gossip columns as the Jolly Set. When Cleveland’s café society proved too tame, he began making overnight commutes to New York, flying into the city to close down the Copacabana nightclub, then flying home the next morning.

Inevitably, the 1949 season was an anticlimax. The Indians dropped to third place as attendance fell by more than 300,000. Veeck continued to rev his promotional engine, but he could not top himself. When the club was eliminated from the pennant race, he staged a funeral at the ballpark and buried the 1948 flag. That stunt outraged some of his players and fans. Before the season was over he was looking to sell.

Although he said the thrill was gone in Cleveland, Veeck sold because he needed cash to settle his divorce and provide trust funds for his and Eleanor’s three children. He seldom saw the children after that. His middle child, Peter, met him only twice between the ages of 8 and 23. His daughter Ellen said her mother became withdrawn following the divorce, “so I feel as if I have been raised as an orphan.” 9

While negotiating to sell the team, Veeck was taking instruction to convert to Catholicism. He had fallen in love with Mary Frances Ackerman, a vivacious publicist for the Ice Capades show, and she wanted to be married in her church. The Catholic Church did not recognize divorce; some of Veeck’s associates said church authorities granted him a dispensation because his first wedding had been performed in the Episcopal faith. He and Mary Frances were married on April 29, 1950. He had found his life partner. She joined him as a host of radio and television shows, and as an energetic public speaker promoting whatever team he owned. They also produced six children. (His son Mike said later, “My father loved baseball so much he had nine kids. When the DH was introduced, my mom left town.” 10)

The couple moved to Veeck’s Arizona ranch, but not for long. Civic leaders from Milwaukee, Los Angeles, and other cities wanted him to buy a major-league club and bring it to their area. Veeck set his sights on the St. Louis Browns, the American League’s perennial doormats. The team had won its only pennant in the wartime 1944 season, when its draft rejects proved stronger than the competition’s. The Browns were poor stepchildren to the Cardinals in the majors’ smallest two-team market. Visiting teams complained that their share of the sparse gate receipts did not even cover travel expenses.

When Veeck bought the Browns in July 1951, it was widely predicted that he would move the franchise, but he later insisted that he planned to run the Cardinals out of town. On his first night as owner he served a free beer or soda to everybody in the ballpark. Six weeks later, he pulled his most famous stunt. Three-foot-seven-inch Eddie Gaedel popped out of the Browns’ dugout to lead off in the second game of a doubleheader against the Tigers. After manager Zack Taylor showed the umpire that Gaedel had, indeed, signed a contract (Veeck mailed it to the American League office too late to get there before game time), the tiny man squeezed into a deep crouch at home plate, displaying a strike zone slightly larger than a matchbox. Veeck threatened to shoot him if he swung the bat.

As the largest crowd in nearly four years whooped with delight, Detroit catcher Bob Swift dropped to his knees and pitcher Bob Cain delivered four high ones. Gaedel trotted to first base, slapped his pinch-runner on the backside, and ran to the dugout waving his cap. Humorist James Thurber had written a story years before about a midget batting in a big-league game, but Veeck said he had never heard of it.

Five days after the Gaedel game, Veeck struck again with Grandstand Manager Night. He handed out placards printed with “Yes” and “No” to fans sitting behind the home dugout, and at key points in the game they were asked to call the plays: Steal? Bunt? Hit-and-run? Manager Taylor watched from a rocking chair, puffing his pipe, while the Browns beat the Athletics.

Veeck had gone too far. He had inserted his stunts into the ballgame — made a mockery of the game, in the eyes of his many critics. But the Browns’ attendance improved in the second half of the season, even though the team finished last. In 1952 attendance nearly doubled, but it was still the lowest in the league as the club rose only one slot in the standings.

The Internal Revenue Service brought Veeck down, although it had nothing to do with his own shaky finances. Cardinals owner Fred Saigh was convicted of income-tax evasion and forced to sell his club. At first it looked as if Veeck had won; a Houston group put in a bid. But August A. Busch Jr., owner of the giant Anheuser-Busch brewery, stepped up to keep the Cardinals in St. Louis. Veeck knew his game was over: “I wasn’t going to run Gussie Busch out of town.”11

Within weeks he struck a deal to move the Browns to Baltimore. His fellow owners turned him down. He had enraged them not only with his stunts, but by proposing the “socialistic” idea of sharing television revenue. “The vote against me was either silly or malicious,” he said, “and I prefer to regard it as malicious.”

Now he was a lame duck in St. Louis — “a villain without any money,” in his words. He sold Sportsman’s Park, where the Cardinals had been his tenants, to Busch for $800,000. During the 1953 season he sold several players, as well as his Arizona ranch, to stay afloat. In their last game the Browns ran out of new baseballs and had to use scuffed warm-up balls. At the end of the season, AL owners again blocked Veeck from moving to Baltimore. Defeated, he sold the club to a Baltimore syndicate, and the league instantly approved the transfer of the franchise. “They didn’t care whether they bought him out or froze him out,” John P. Carmichael of the Chicago Daily News wrote. “Just so they got even with him, after five years, for disturbing the old, established order of things.” 12

Veeck was again searching for a way to get back into the game. He tried to buy the Philadelphia A’s and the Detroit Tigers. He worked with the governor of California on bringing major-league ball to the West Coast. He even negotiated to buy the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus; he said people had been telling him for years that he belonged in a circus. He scouted for the Indians, where his friend Hank Greenberg was general manager, and spent one season running the Triple-A Miami Marlins. He served as a commentator on NBC-TV’s Game of the Week.

A family feud finally opened a door. When White Sox president Grace Comiskey died in 1956, she left the majority ownership of the club to her oldest child, Dorothy Rigney, rather than her son, Charles Comiskey II. Thirty-one-year-old Chuck Comiskey, who was running the team, was now a minority owner and bitterly resented it. The club’s board of directors was deadlocked, with two votes controlled by Chuck and two by Dorothy. She owned 54 percent of the stock, not enough to appoint a fifth member.

Worn down by two years of squabbling, Mrs. Rigney told her lawyers to find a buyer. Veeck put together a group of local and out-of-town financiers to acquire an option on her shares. Although he had sold the Browns for a small profit, Veeck had no money, but he never had a shortage of willing investors. He offered $2.7 million for her 54 percent, valuing the franchise at $5 million. Mrs. Rigney’s lawyers told him that Chuck would be given a chance to match the price, but Veeck said young Comiskey submitted a lowball offer.

The Veeck group exercised its option in February 1959. Chuck Comiskey sued to block the sale. In the coming months he would paper the courthouses with lawsuits. He lost them all. Veeck said later, “Chuck had grown up firmly convinced that the divine order of the universe called for the earth to spin on its axis, the sun to rise in the east, and Charles Comiskey II to preside over the fortunes of the White Sox.”13

Comiskey vented his resentment in pettiness. Since he was the highest-ranking officer of the corporation, he declared that Veeck and his partner Hank Greenberg “can’t be on the payroll unless I sign the checks.” When Veeck came to Comiskey Park on the day after the sale closed, Comiskey left the building. “I won’t talk to Veeck as far as business is concerned,” he huffed.14 Veeck invited sportswriters to “have 54 percent of a cup of coffee.”15

Comiskey’s petulance was more than an annoyance. Veeck structured the deal so that most of the purchase price went to buy the players’ contracts. Players were assets just like the ballpark and the groundskeepers’ rakes and shovels. Since a player’s value declined as he got older, he was an asset that could be depreciated to reduce the corporation’s taxes. Under IRS rules, Veeck and his partners needed to own 80 percent of the stock to take advantage of the depreciation scheme. He claimed they could save $2 million in taxes — if Chuck would sell. Chuck would not. Veeck never got his tax break, but other sports-team owners did, for decades afterward.

Veeck and Comiskey put aside their differences to appear together at the 1959 home opener. Left-hander Veeck threw out the first ball, and Comiskey caught it. Then a fusillade of fireworks erupted in left field. At the seventh-inning stretch, each of the 19,303 fans was invited to have a free beer. Bill Veeck was back. But the front-office truce was strictly for public consumption. Comiskey continued his court fights, while Veeck mostly ignored him. Greenberg became the unwilling go-between.

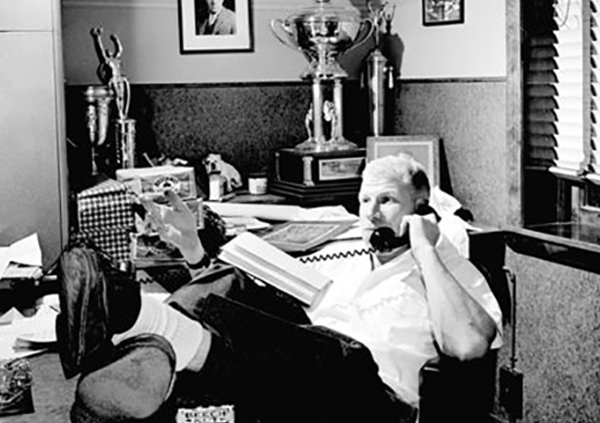

Veeck threw his frenetic energy into filling Comiskey Park, making as many as three speeches a day and appearing on radio and television shows from morning till midnight. One morning he showed up at his office at 5 A.M., startling the night watchman. He spent a reported $150,000 painting and scrubbing the old ballpark.

He gave away orchids on Mother’s Day. In the same game, the “lucky chair” prize was 36 live lobsters. Other fans received 1,000 cans of beer, 1,000 pies, 1,000 bottles of root beer, 1,000 cupcakes, and 100 free restaurant dinners. “You give a thousand people a can of beer and each of them will drink it, smack his lips and go back to watching the game,” he wrote. “You give a thousand cans to one guy, and there is always an outside possibility that 50,000 people will talk about it.”16 He also staged free days for cab drivers and bartenders, believing they were valuable public-relations boosters for the club. After fans booed left fielder Al Smith, Veeck let everyone named Smith (or Smythe or Schmidt) in free as Al’s guests. Comiskey Park attendance reached a franchise-record 1,423,144, but it fell just short of the Chicago record set by Veeck’s father’s Cubs in 1929.

Veeck’s assessment of his new team: “I spent the first two-thirds of the season predicting that we didn’t have enough power to beat the Yankees.”17 But manager Al Lopez assured him the White Sox could win. As a result, Veeck made few changes in the roster. His only additions were three over-the-hill veterans. Two-time All-Star outfielder Del Ennis lasted seven weeks before he was released. Outfielder Suitcase Simpson batted only .187 before he was traded to Pittsburgh on August 25 for 34-year-old first baseman Ted Kluszewski. Big Klu had been a slugging star for Cincinnati, but chronic back problems had sapped his power. He managed just two homers in 31 games for the White Sox, but slammed three in the World Series.

The White Sox took over first place for good on July 28. Veeck remarked, “Who ever thought that a team could win a pennant strictly on pitching, defense, and speed on the bases? Certainly I didn’t. This is contrary to everything I’ve learned about baseball.”18 He gave all the credit to Lopez. Preparing for the Sox’ first Series since the infamous Black Sox, Veeck again sold tickets on an individual-game basis after collecting the names and addresses of fans who had supported the club for years. “These are our vvvvips,” he said. “Our very, very, very, very important persons.”19

After Chicago battered the Dodgers 11-0 in Game One, it looked as if Lopez’s assessment of the team was correct. But when Los Angeles claimed the championship, Veeck said ruefully, “We got licked by the one thing we didn’t have in common: power.”20 A joke made the rounds: the White Sox would change their name to White Nylons, because nylons get more runs.

Veeck set out to fix that. In his search for power, he traded away much of his club’s future. Six young players went out the door: catchers Earl Battey and John Romano; first basemen Norm Cash and Don Mincher; 20-year-old outfielder John Callison; and pitcher Barry Latman. Every one was a future All-Star. The deals brought in two of Veeck’s favorites, both past their primes. Thirty-three-year-old first baseman Roy Sievers had played for him with the Browns. He had signed outfielder Minnie Minoso for Cleveland, but traded the Cuban Comet to the White Sox before he became a star. Minoso was somewhere in his mid-30s; his exact age remains in dispute. Veeck also acquired some younger talent, 26-year-old third baseman Gene Freese and 25-year-old pitcher Frank Baumann.

Defending the deals, Veeck said, “It has been my impression that Youth Plans and Five-Year Plans lead not to pennants, but only to new Five-Year Plans.”21 The impatient Veeck simply refused to wait for prospects to develop. The White Sox fell to third, fourth, and fifth over the next three years. They did not reach the postseason again until 1983.

In 1960 Veeck introduced his most lasting innovations. He put players’ names on the backs of their road uniforms (names were added to home uniforms the next year) and built an exploding scoreboard to celebrate the home team’s home runs. “It shrieks, wiggles, burps, whines and twinkles,” The Sporting News marveled. “Fireworks explode beneath the scoreboard while tape recordings give out virtually every sound imaginable … a cavalry charge, machine-gun fire, two trains crashing head-on, subway screechings, jet bombers, and a woman screaming, ‘Fireman, save my child.’”22 The cacophony delighted fans and infuriated opponents. Cleveland outfielder Jimmy Piersall threw a baseball at the board. Casey Stengel orchestrated a puckish response: After Mickey Mantle hit a homer, Stengel and the Yankees paraded in front of the visitors’ dugout waving sparklers. Most other teams eventually added names to their uniforms and sound-and-light shows to their scoreboards.

The 1960 White Sox broke the Chicago attendance record with more than 1.6 million, but Veeck was suffering frightening health problems. The chain smoker broke down in coughing fits that sometimes caused him to pass out. In April 1961 he went to the Mayo Clinic for tests. Doctors diagnosed a variety of ailments, and prescribed retirement. Veeck sold his share of the team to one of his partners, Arthur Allyn Jr.

The 47-year-old Veeck moved his family to a Maryland farm on the shore of Chesapeake Bay. He called the place Tranquility. In 1962 he published his autobiography, Veeck as in Wreck, co-authored by sportswriter Ed Linn. The book is both joyful and bitter. He settled some old scores and lobbed new grenades at the baseball establishment. The final lines read: “Sometime, somewhere, there will be a club no one really wants. And Ole Will will come wandering along to laugh some more.

“Look for me under the arc-lights, boys. I’ll be back.”23

Over the next few years Veeck wrote a newspaper column, captivated the many sportswriters who made the pilgrimage to Tranquility, and recovered his health. Reflecting on his many hospital stays, he said, “Suffering is overrated.” While watching local Little League games, he discovered a 12-year-old with a sweet swing, Harold Baines. He and Linn wrote another book, The Hustler’s Handbook. He tried to revive a failing Boston racetrack, Suffolk Downs, and wrote a book about the experience, Thirty Tons a Day – the horses’ major output.

By 1970 he was ready to scratch his baseball itch. He tried to buy Washington’s struggling expansion team before owner Bob Short moved it to Texas. His friend Jerry Hoffberger put the Baltimore Orioles up for sale, and Veeck thought he had a deal, but Hoffberger backed out. Baltimore Sun writer Bob Maisel believed Hoffberger was afraid Veeck would sell the team after a few years, and would not care if the next owner took the Orioles away from Baltimore.

For a man lusting to get back into baseball’s club, Veeck did himself no good when he testified in support of Curt Flood’s court challenge to the reserve clause. He described a ballplayer’s condition as “human bondage,” but said the reserve clause should be phased out gradually to avoid chaos.24 Veeck, Hank Greenberg, and Jackie Robinson were the only other baseball men to testify on Flood’s behalf.

In 1975 Veeck learned that the White Sox were for sale. Owner John Allyn, who had bought control of the team from his brother Arthur, was near bankruptcy. Attendance had sagged as fans stayed away from the deteriorating neighborhood around Comiskey Park. The franchise was on the verge of being transferred to Seattle. The 61-year-old Veeck put together a group of more than 40 investors, including Greenberg and onetime White Sox manager Paul Richards, but American League owners rejected the bid. They said Veeck’s deal was too dependent on borrowed money. That was the public explanation. Several owners acknowledged their distaste for a man who had ridiculed and criticized them for years. After Veeck raised additional cash, they voted him down again. It wasn’t the deal they disliked, it was the dealer. Then Detroit Tigers owner John Fetzer told his colleagues that Veeck had done everything they asked: “Look, I don’t like it any more than you do that we’re allowing a guy in here who has called me a son-of-a-bitch over and over. But, gentlemen, we’ve got to take another vote.”25 Many of them may have been biting their tongues, but they approved him by 10-2 — one more than the three-fourths majority necessary.

Veeck greeted the vote by kicking his wooden leg high above his head. Then he put up a sign saying “Open for Business” in the hotel lobby where the winter meeting was being held, and spent 14 hours making trades in public. On his first day after being re-admitted to the club, he was already horrifying his fellow owners. Milwaukee’s Bud Selig fumed, “This is a meat market.”26

Veeck had only 13 days to celebrate his comeback. On December 23 arbitrator Peter Seitz abolished the reserve clause that bound players to their teams for life. Ruling on grievances by pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally, Seitz said the clause allowed a team to renew a player’s contract for one year, not over and over forever, as the owners had maintained and players had long believed. The decision opened the door to free agency and the spiraling salaries that came with it. Veeck was short of working capital, with no margin for error. As soon as he got back into the game, he was on his way out.

He would not go quietly. The party started on opening day. To celebrate America’s Bicentennial, he re-enacted Archibald McNeal Willard’s famous painting of “The Spirit of ’76.” Wearing bandages and uniforms of the Revolutionary army, Veeck wore a peg leg and played a fife; his longtime sidekick Rudie Schaffer beat a drum; and manager Paul Richards carried the American flag as the trio marched across the field. The stunts continued nonstop throughout the season: a bevy of belly dancers, parades of horses and cattle, nightly prizes for random fans. He outfitted the players in Bermuda shorts for a few games. He put coach Minnie Minoso, who was said to be 53 years old, in the lineup as a designated hitter. Comiskey Park attendance jumped by 20 percent, to 915,000, but it was only 10th highest in the league. The White Sox finished last.

Veeck told general manager Roland Hemond, “Don’t bother drawing up a budget. We don’t have any money. We’ll think of something.”27 But he still worked and played for 20 hours a day, drinking two dozen beers and smoking up to four packs of Salem Longs, stubbing out the butts in an ashtray built into his prosthetic leg. Hemond said, “I tell people I worked for Bill Veeck five years, but it was really ten because I never slept.”28

In 1977 Veeck found an angle and nearly rode it to glory. His plan was “rent a player.” He acquired players who were a year away from free agency, knowing he could not afford to keep them. With sluggers Richie Zisk and Oscar Gamble, the “Go-Go Sox” were transformed into the “South Side Hit Men.” The team belted 192 homers, second-most in the majors, and won 90 games. They contended for the Western Division championship for much of the season before sinking to third place. Veeck broke his own Comiskey Park attendance record with more than 1.6 million and was named Major League Executive of the Year by The Sporting News.

It was downhill from there. He told the fans, “We will scheme, connive, steal, do everything possible to win the pennant — except pay big salaries.”29 The average player’s paycheck more than doubled in just three years, driven by free agency and salary arbitration. Veeck could not keep up. He hired Larry Doby as the majors’ second black manager, but fired him after less than a full season. The next year he hired Tony La Russa, a 34-year-old career minor leaguer, to run the club.

Veeck’s doomed second time around in Chicago hit bottom on July 12, 1979, Disco Demolition Night. It was an ill-begotten attempt to attract young people and show that the Sox were “hip.” Bring a disco record, buy a ticket for 98 cents, and watch as the records were blasted to smithereens between games of the doubleheader. An overflow crowd crashed the gates, and they soon began sailing their discs onto the field. Fueled by beer and marijuana, thousands spilled out of the stands and ran amok. The second game was forfeited to visiting Detroit.

By 1980 Veeck’s luck, money, and health had run out. The 66-year-old’s hearing and eyesight were failing; he suffered from emphysema and underwent an operation on his remaining leg. But he could not even leave the game without controversy. When he agreed to sell the White Sox to shopping-mall magnate Edward J. DeBartolo, the American League refused to approve the deal on the grounds that DeBartolo would be an absentee owner who also owned racetracks. DeBartolo suspected the real reason was his Italian heritage, with its stereotype of Mafia connections. Veeck said, “I’ve never been ashamed to be a member of the American League — but I am now.”30

Chicago real-estate developer Jerry Reinsdorf and television entrepreneur Eddie Einhorn bought the club. At their first press conference, Einhorn promised to run a high-class operation. Veeck was insulted, and never again went to Comiskey Park. Einhorn later insisted he meant no offense, but did not back away from his criticism of Veeck’s operation. “He called his ballpark the world’s largest outdoor saloon, and was proud of it,” Einhorn said. “We came in immediately and tried to change that image. And we succeeded in making it a family place to be.” 31

Veeck returned to his roots as a Cubs fan, and became a regular in the raucous Wrigley Field bleachers. In 1984 he contracted lung cancer. He died at the age of 71 on January 2, 1986. His cremated remains were interred at Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago. He and Mary Frances had been married for 35 years. She said, “It was a romance from beginning to end.” 32She continued to live in Chicago, and when the White Sox won the 2005 World Series, the club gave championship rings to her and members of the Comiskey family.

Besides Wrigley Field’s ivy, Bill Veeck’s baseball legacy is his son Mike, part-owner and flamboyant promoter of several minor-league teams. Mike’s most infamous stunt was Vasectomy Day — a fan would get a free one on Father’s Day — but that was aborted by religious opposition. He said of his father, “He had this tremendous sense of the absurd, and he gave that to me.”

Veeck was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1991. His enemies on the Veterans Committee kept him out until he was dead, as they did with Leo Durocher. His plaque at Cooperstown reads, “A Champion of the Little Guy.”

Notes

1 Gerald Eskenazi, Bill Veeck: A Baseball Legend (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1988), 5.

2 David M. Jordan, Larry R. Gerlach, and John P. Rossi, “The Truth About Bill Veeck and the ’43 Phillies,” SABR’s The National Pastime, No. 18, 1998.

3 Jules Tygiel, “Revisiting Bill Veeck and the 1943 Phillies,” Baseball Research Journal 35, 2007.

4 Bill Veeck with Ed Linn, Veeck As In Wreck (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2001; originally published 1962), 80.

5 Ross Newhan, “Red Patterson Dies of Cancer,” Los Angeles Times, February 11, 1992.

6 Veeck, 105.

7 Veeck, 105.

8 Veeck, 208.

9 Eskenazi, 55.

10 http://thepastime.net/, accessed on June 28, 2008. An account of Mike Veeck’s speech at the 2008 SABR convention in Cleveland.

11 Veeck, 229.

12 Eskenazi, 113.

13 Veeck, 318.

14 “No Meetings for Comiskey,” Baltimore Sun, March 12, 1959.

15 Baltimore Sun, March 12, 1959.

16 Veeck, 340.

17 Veeck, 334.

18 Jerry Holtzman, “Pale Hose Kicking Up Heels in Steps of Hitless Wonders,” The Sporting News, August 19, 1959.

19 Veeck, 351.

20 John Carmichael, “World Series Post Mortems: Sox Too Daring on Bases,” The Sporting News, October 21, 1959.

21 Veeck, 141.

22 Jerry Holtzman, “Dykes Blasts Veeck’s ‘Pin-Ball’ Scoreboard,” The Sporting News, May 11, 1960.

23 Veeck, 379.

24 Eskenazi, 148-49.

25 Veeck, 382.

26 Veeck, 383.

27 Roland Hemond, interview with the author, October 18, 2006.

28 Hemond.

29 Wayne Stewart, editor, The Gigantic Book of Baseball Quotations (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2007), 105.

30 Dick Kaegel, “Dealer Herzog — Where Action Is,” The Sporting News, December 27, 1980.

31 Eskenazi, 177.

32 Ira Berkow, “When Baseball’s Circus Came to Town,” New York Times, October 20, 2005.

Full Name

William Louis Veeck

Born

February 9, 1914 at Chicago, IL (US)

Died

January 2, 1986 at Chicago, IL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.