Marvin Miller

When walking through the exhibits at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, it is difficult not to absorb slices of the game’s history and lore, and to learn about the role the sport has played in both American and world history. It also quickly becomes clear that the stories of the players and the managers and the executives are each cast in a fashion that is positive and uplifting.

When walking through the exhibits at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, it is difficult not to absorb slices of the game’s history and lore, and to learn about the role the sport has played in both American and world history. It also quickly becomes clear that the stories of the players and the managers and the executives are each cast in a fashion that is positive and uplifting.

Thus, it is difficult to envision any member of baseball’s Hall of Fame having been publicly reviled by ownership — and some fans — during the prime of, and even well after, his career.1 Conversely, few of those elect immortals have left a sweeping legacy that continues to shape the landscape of baseball.

Marvin Miller was such a man. His work as the executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association from 1966 to 1982 not only reshaped how baseball players were and are compensated, but also recast the entire financial structure of professional sports. Before Miller’s ultimate election to Cooperstown, Hank Aaron said, “Marvin Miller should be in the Hall of Fame if the players have to break down the doors to get him in.” Tennis great Arthur Ashe noted that, “Marvin Miller has done more for the welfare of black athletes than anyone else.” Red Barber claimed that Miller, “along with Babe Ruth and Jackie Robinson, is one of the two or three most important men in baseball history.”2 Perhaps such greatness in the collective eye of constituents is possible only at the cost of anger and repression by those who were opposed.

For baseball fans born after 1980 or so, there is little direct memory of the time when players were truly undercompensated in relation to the revenue they generated for their respective teams. In 2013, Graham Womack published an analysis at The Hardball Times in which he converted the salaries of prominent Hall of Famers to modern dollars. Players like Babe Ruth, one of the immortal players in the game who changed how baseball was played, earned the equivalent of $1.44 million in 2012 dollars, and he was easily the best-paid player of his time. Willie Mays’s 1959 salary equated to less than $1.3 million in 2012.

After Marvin Miller’s tenure as head of the Major League Baseball Players Association ended in the early 1980s, star players were making $3.5 million or more. The rank-and-file players — who were subject not only to glacial salary increases but also to salary reduction if the team decided performance did not merit the money — benefited even more.3 Teams drove the salary negotiations. The players, continuously reminded they were just lucky to have a job playing a game, were virtually powerless. Compounding that problem was the notorious “reserve clause,” a contractual codicil that effectively bound a player to the team with which he signed unless he chose to retire. The team, of course, could drop or trade the player, but the product, the player, had no real say in where he played. That all ended during Miller’s reign. In 2021, the average major-league player salary was $4.17 million.4

The average big-leaguer today has far more buying power than Reggie Jackson in 1982, or Rod Carew in 1979 or Hank Aaron in 1972. There are of course other factors at work besides inflation. The US economy and professional sports in particular have grown at an exponentially faster rate. That just underscores how the quality of life for a major-league baseball player has improved by orders of magnitude. Marvin Miller’s legacy is almost impossible to quantify.

Marvin Julian Miller was born on April 14, 1917, to Alexander and Gertrude Wald Miller in the New York City borough of the Bronx. Alexander was a Russian émigré, having been brought to the United States as an infant. He carved out a successful life as a clothing merchant in New York’s Garment District. Gertrude was seven years younger than Alexander and enjoyed a long career as a public school teacher in and around New York City. Miller had only one sibling, a sister, Thelma, six years his junior.5 They were raised in a stable, nurturing environment.

After graduating from James Madison High School, followed by a year at St. John’s University in 1934 and then two more at Miami University in Ohio, Marvin finally earned an economics degree from New York University in 1938. Following a year of working odd jobs as the country emerged from the Great Depression, Miller accepted an entry-level position at the US Treasury Department. In 1939, he also married Theresa “Terry” Morgenstern, a union that lasted nearly seven decades.

In 1940, the Millers returned to New York when Marvin took a job as an investigator with the New York City welfare department. When the US entered World War II, Miller was given a 4F rating by the military draft board. The judgment stemmed from an early childhood shoulder injury, the effects of which lasted Miller’s entire life. In 1942, it was back to Washington, DC, this time working for the War Production Board in a position to protect both the government and workers from unscrupulous businesses seeking to profit from increased federal wartime spending.

At the end of the war, the Millers welcomed son Peter Daniel into the family. With this new responsibility, Miller left the government and took his first union job with the International Association of Machinists and the United Auto Workers. Two years later, in 1949, Marvin and Terry had their second child, daughter Susan Toni.

In 1950, Marvin settled into a labor negotiation job with the United Steelworkers. He had begun his career as an economist but over time moved into arbitration. In that role, he was directly exposed to continual conflict between workers and management, and he found his sympathies lay more with the former than the latter. With the Steelworkers he was just a cog in an enormous machine, but his abilities eventually led him to a position as the head of the union’s Human Relations Committee. In that job, he proposed what became the Kaiser Steel Long-Range Sharing Plan, “a formula for sharing the increased profits with employees.”6

Organizational politics may have disenchanted Miller, and in December 1965, when his former boss at the National War Labor Board, George W. Taylor, told Miller about Robin Roberts and the Major League Baseball Players Association’s search for a new director, Miller listened. In early 1966, Taylor connected the pitcher and the economist, and Roberts explained the requirements of the job.7 The association had looked at several other candidates — including a few potential shills for the owners along with former Vice President Richard Nixon — but Roberts and Jim Bunning were united in their pursuit of Miller.

Bunning remembered, “We opened up a meeting to suggestions and someone threw out his name. I was one of the players who went and interviewed him. … He saw the need for the job.”8 The average player salary in 1966 was $19,000 per year. Still, the players saw no opportunity for change. “The first thing you learned when you came to the big leagues,” Curt Flood said years later, “was to never discuss salaries.”9

In early 1966, Miller was hired as the second full-time executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association. (Frank Scott had served in the same role beginning in 1959, at first on a part-time basis.) His first contract was a two-year deal at an annual salary of $50,000. After six months of visiting teams and introducing himself to both players and executives, listening to respective concerns and plans and assessing his new working environment, Miller hung out his figurative shingle in New York on January 1, 1967.10 For his part, Miller entered his new job with sincere humility. He said, “This is a very democratic organization. My job will be to keep it that way. … There won’t be any move toward dictatorial action or move to make this organization act as a union. For example, the players have always carried on salary negotiations on an individual basis with their respective clubs and I really don’t expect to get involved in that matter.”11

To a great degree, Miller was true to his stated intention. That is not to imply that the new executive director was a passive observer. As events played out over the next decade, Miller proved to be precisely the right man in the right place at the right time to liberate baseball from its stodgy past.

In late 1969, the St. Louis Cardinals notified All-Star outfielder Curt Flood that he had been traded to the Philadelphia Phillies. Flood demurred, in defiance of the expectations of baseball ownership. For the next three years, Flood pursued a legal remedy to what he considered an unfair restriction in the standard player’s contract, one that allowed teams to send him to any other team without input from the affected athlete. Miller advised Flood along the way, resolutely standing with the player as he took his case all the way to the United States Supreme Court.

“Curt Flood came to me to discuss the possibility of a lawsuit and I thought it was a losing case. … How was he going to finance it?” Miller said later. “I was concerned how easy it was to make bad law with a bad case – and I felt the union should back him.”12 Rather than allow Flood to walk the legal path alone, he convinced the Players Association to support what they knew to be a losing cause. In such moments, unity and strength grow.

Flood’s appeal was ultimately denied, but that episode also reinforced Miller’s understanding of baseball economics. The reserve clause was the center of gravity for the owners, the magnates, and eliminating that tiny bit of the standard contract could liberate players in unimaginable ways and unfetter a game stalled in a model more appropriate for 1875 than 1975.

“I remember my feelings at the time,” Miller said in a 2004 oral history interview, “a feeling of indignation when reading about the reserve clause. … Indignation is justified here … this (clause) was immoral behavior.”13 From the start of his tenure as executive director, Miller had not set out to take on the reserve clause immediately. Instead, he adapted his well-honed strategy, built over years of labor dispute adjudication in the public and private arenas, of incrementally building precedent and appropriate conditions in anticipation of action. Flood’s case was one of the most visible supporting elements of Miller’s machine.

The next available target for Miller was the players’ pension fund. In remarks offered in 2012, he noted that “where we asked that they (the owners) consider increasing the pension benefits to reflect the cost of living that had risen in the three years since we had last negotiated, the owners’ response was, ‘Not a cent. We’re not going to do it. Reason? No reasons. The union has gone far enough.’ ”14

Miller did not simply pick an arbitrary fight with the owners. Rather, he chose an issue which would translate more easily to public understanding. Inflation was beginning to spiral upward in the early 1970s. The notion of a pension fund, some modest financial security at the end of a life of labor, was shared by much of working America, and the idea that wealthier baseball team owners could withhold affordable benefits on mere whim gave the union’s campaign an underpinning of virtue.

Throughout his life, Miller almost always maintained a sober and calm demeanor regardless of the situation. Instead of railing at the owners’ collective truculence, he began to advise the players to consider a strike before the 1972 season began. “I never did celebrate a strike,” Miller said. He did, however, “make a sharp distinction between celebrating a strike and celebrating a strike’s results.”15 The players voted 663-10 to stop work. When the existing pension agreement between players and owners expired on March 31, the players formally and collectively went on strike, the first organized labor rebellion in the game’s history.16 Miller later said that a strike was the last thing he intended.17

By the time play resumed after the 14-day strike, including what would have been the opening 13 days (86 games) of the 1972 season, the pension fund was $500,000 richer (a 17% cost-of-living increase), and the players had gained a degree of access to an individual salary arbitration process.18 There had been plenty of finger-pointing by the owners at the players and the union chief, along with accusations of bad faith and general disgust. Yet Miller and his constituents generally stayed out of the name-calling fray.

With these two moves, the Flood defense and the pension/arbitration victory, Miller had gained the full confidence of the players. New York Yankees pitcher Rudy May said, “Any time Marvin Miller whispers ‘Strike’, every major league player is going to scream it at the top of his voice. Man, don’t the owners know that there’s going to be a whole generation of ballplayers’ sons who grow up with the middle name Marvin? After all that this man has done for us, who’s going to be ungrateful enough not to lose some paychecks if we have to?”19

Digging deeper, it appears that among all the economic progress that Miller helped bring to baseball and professional sports in general, his most underrated accomplishment may have been the unification of the entire inventory of players into a single, coherent whole. That feat, fostering an underlying threat that the tightly organized, unified, and motivated aggregation of players represented to the owners, gave Miller and the association a tool of vast power. With that weapon, it was, Miller believed, time to set the wheels in motion to overturn the reserve clause.

Because of Miller’s relentless pressure, the owners had finally agreed that labor disputes should be settled by arbitration whenever possible. Owners saw the concession as a path to avoiding future work stoppages. Meanwhile, Miller had discovered a legally binding opportunity to change the game once and for all. The first application of arbitration came in the case of Jim “Catfish” Hunter in 1974.20 Hunter was the ace of the three-time World Series champion Oakland Athletics, and when A’s owner Charlie Finley reneged on a contracted payment, Miller took the case to arbitration. The decision made Hunter a free agent, and he used that opportunity to sign with the New York Yankees for $3.5 million.

Miller’s lifelong athletic outlet was tennis. Even with the shoulder injury that had hindered him since youth, Miller and wife Terry both enjoyed the competitive outlet that the sport offered. It was in the arbitration process, though, that Miller channeled what might be characterized as a sort of latent aggression to spectacular result. In 1974, Miller had decided that he needed a reliable case, a situation in which a player was still performing well enough to be of value, but who was also willing to challenge the existing contractual system. Andy Messersmith was in the prime of his career and Dave McNally was nearing the end of his career. Each player was willing to test the uncharted waters of free agency.

Both pitchers agreed to play out their contract, refuse to re-sign with their teams, then petition for free agency. The owners naturally balked at this idea, and the Players Association requested arbitration for the players. In December 1975, arbitrator Peter Seitz ruled that the owners had not provided sufficient justification to keep the players tethered to their former teams, that Messersmith and McNally had fulfilled their contracts, and that they were free to negotiate with other teams as desired. The decision did not matter to McNally, who retired to Montana, but enabled Messersmith to set a new trajectory in player salary negotiations.

For his part, Miller was wise enough to concede to ownership that free agency should not be so easily accessed. By convincing the owners to adopt a progressive salary arbitration for players with fewer than six years of big-league service, and permitting free agency only after that point, he ensured that the labor pool would not be annually saturated. That would have reduced available salaries by creating too much of the valuable resource, the players. By restricting that resource, by creating scarcity, he engendered a system that both rewarded the best players and created a forum in which the owners were compelled to competitively bid for the resource. Salaries would inevitably rise, but the freedom of players to move among teams would create an opportunity for interested teams, who could afford to do so, to sign superstars.

A brief, eight-day strike in 1980 presaged the notorious 50-day work stoppage of 1981 from June 12 to July 31. The latter action cost baseball 712 games and forced the major leagues to modify both the regular and postseasons to accommodate first- and second-half champions.21 Although a settlement was reached on July 31, play did not resume until more than a week later. The All-Star Game was played on August 9, and the season’s second half commenced on the following day.

The union had originally planned to strike on May 29 but were forced to delay two weeks while awaiting a hearing by the National Labor Relations Board. It was rumored that the owners’ negotiator, Ray Grebey, and Miller were so angry with each other following the contentious negotiations that they refused to appear together for a photograph following the resumption of play. Evidently the two mended their figurative fences, and in 2009 Grebey wrote a letter to the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Board of Directors urging Miller’s election. “No other individual player,” he wrote, “played a more prominent role in creating the structure and process within which today’s game is played. History will not ignore Miller’s role in reshaping the game of baseball.”22

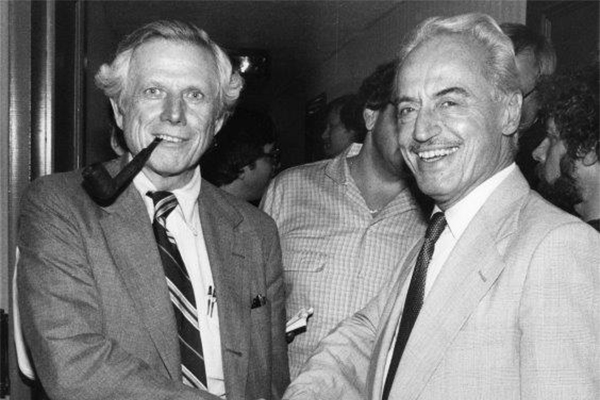

Ray Grebey, left, and Marvin Miller shake hands following the end of the 1981 baseball labor dispute. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Miller retired from the Players Association in 1982. His impact has been profound and undeniable. The ability of players to become free agents, able to sell their skills to whomever they chose, made baseball not only fun for the fans, but incredibly lucrative for the players. According to researchers at the Baseball Hall of Fame, “Free agency began in earnest following the 1976 season, when the average major league player was making $50,000 per year. When Miller retired in 1982, the average salary was $241,497.”23

In 2011, looking back on his accomplishments, Miller allowed himself to reflect. “I’m proudest of the fact that I’ve been retired for almost 29 years at this point, and there are knowledgeable observers who say that this might still be the strongest union in the country. I think that’s a great legacy.”24 In one of his final public appearances, he summarized his perspective:

“Consider that major league baseball is really a labor-intensive industry. By that, I mean it’s an industry where the labor costs are disproportionately more than other costs than in most other industries that are not labor intensive. Yet in a labor-intensive industry with a tremendous rise in players’ salaries and benefits, there along with it came this record of attendance and profits and revenue of the owners. In other words, just speaking for myself for the moment, I never before saw such a win-win situation in my life, where everybody involved in major league baseball, both sides of the equation, just still continue to set records in terms of revenue, profits, salaries, and benefits, and so on. You would think that it wasn’t possible to do that, but it is possible, and it is an amazing story how under those circumstances — that there can be both management and labor really winning out.”25

Marvin’s wife Terry had retired from her associate professorship at City University of New York in 1980, and the Millers lived out their lives in their Manhattan home. Terry passed away in 2009. In the summer of 2012, Miller was diagnosed with liver cancer, and on November 27, he died in his home at the age of 95. The baseball world had a chance to remember Miller at a memorial service held in the Tishman Auditorium at New York University, and a series of former players spoke about how Miller’s greatest contribution was not the contractual improvements across the game, but in educating the players about the system and how to change the status quo.26 In lieu of burial, Miller donated his body to medical researchers at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City.27

In 1991 Miller published his memoir, A Whole Different Ballgame, and in 1997 the Major League Baseball Players Association created the Marvin Miller Man of the Year award. In 2001 Miller was named to the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame. But induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown eluded him during his lifetime.28 Over the years, players and writers lobbied for his election to the Hall of Fame. Miller was, after all, one of the most significant people in the history of major-league baseball. The changes to the entire world of professional sports resonate well into the 21st century.

A few years before his death, Miller requested that he not be selected for an institution that he believed did not share his values. and that he believed the voting process to have been rigged against him.29 In balloting between 2003 and 2010, Miller failed to garner the necessary votes from various Hall of Fame veterans committees that included some of his baseball management adversaries who had once sat across the bargaining table from him over the years.30 In 2010, Miller fell one vote shy of election and he continued to come up short in the years after his death.

Finally, in December of 2019, after several changes to the voting process, Marvin Miller was elected to Cooperstown along with catcher Ted Simmons. (Their induction ceremony, planned for the summer of 2020, was pushed back a year due to the coronavirus pandemic.) At last, Marvin Miller was accepted by the professional baseball establishment. The game is arguably better today, and tomorrow, because of his contributions.

Last revised: April 12, 2023 (zp)

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, and online newspaper archives at Newspapers.com and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 Rick Sage, “Players All Wet, Fans Declare, In Sizing Up the Strike Issues,” The Sporting News, April 22, 1972: 6.

2 Aggregated on the website “Thanks Marvin,” organized by former major-league pitcher Bob Locker in 2012. Accessed online at http://thanksmarvin.com on June 11, 2021.

3 Graham Womack, “How Hall of Famers rank for salary in 2012 dollars,” The Hardball Times, April 2, 2013. Accessed online at https://tht.fangraphs.com/how-hall-of-famers-rank-for-salary-in-2012-dollars/ on August 31, 2021.

4 Christina Gough, “Average player salary in Major League Baseball from 2003 to 2021,” Statista, May 25, 2021. Accessed online at https://www.statista.com/statistics/236213/mean-salaray-of-players-in-majpr-league-baseball/ on August 31, 2021.

5 1930 United States Federal Census: New York/Kings/Brooklyn (District 1280), accessed online at Ancestry.com on August 31, 2021.

6 John Helyar, Lords of the Realm (New York: Villard Books, 1994), 20.

7 Ben Heuer, “The Boys of Winter: How Marvin Miller, Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally Brought Down Baseball’s Historic Reserve System,” Berkeley Law, 2008. Accessed online at http://www.law.berkeley.edu/sugarman/Sports_Stories_Messersmith_McNally_Arbitration.pdf on August 31, 2021; corroborated by Doug Brown, “Player Vote Expected to Okay Steelworkers’ Aid as New Rep,” The Sporting News, March 19, 1966: 6.

8 Joe Gergen, “When Miller headed players’ group, baseball was whole different ballgame,” The Sporting News, July 15, 1991: 5.

9 Gergen.

10 Doug Brown, “Player Vote Expected to Okay Steelworkers’ Aid as New Rep,” The Sporting News, March 19, 1966: 6.

11 Brown.

12 Howard Bloom, “Put Marvin Miller into the Baseball Hall of Fame,” Sports Business News, December 3, 2007. Accessed online at https://web.archive.org/web/20071208081248/http:/sportsbiznews.blogspot.com/2007/12/put-marvin-miller-into-baseball-hall-of.html on August 31, 2021.

13 Fay Vincent, “Marvin Miller,” SABR Oral History Collection, March 26, 2004. Accessed online at https://sabr.org/interview/marvin-miller-2004/ on August 20, 2021.

14 Marvin Miller, “A Celebration of Baseball Unionism: Remarks: Reflections on Baseball and the MLBPA,” New York University Journal of Legislation and Public Policy, 352. April 24, 2012.

15 Miller, “A Celebration of Baseball Unionism: Remarks: Reflections on Baseball and the MLBPA.”

16 William Legett, “Digging in At Crooked Creek,” Sports Illustrated, April 10, 1972. https://vault.si.com/vault/1972/04/10/digging-in-at-crooked-creek

17 Marvin Miller, A Whole Different Ballgame (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1991), chapter 11.

18 “1972 Strike,” SABR/Baseball-Reference Encyclopedia. Accessed online at https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/1972_strike on August 31, 2021.

19 Helyar, 225.

20 Ron Bergman, “Hunter Wins Case, Won’t Play for A’s,” Oakland Tribune, December 15, 1972: 53.

21 Ken Rappoport, “Baseball finally back in business,” Associated Press, August 10, 1981, republished in Paducah (Kentucky) Sun, August 10, 1981: 13.

22 Ronald Blum, “Ray Grebey” Associated Press, September 4, 2013, republished in the San Jose Mercury News. Accessed online at https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/mercurynews/name/ray-grebey-obituary?pid=166799220 on August 31, 2021.

23 “Marvin Miller,” Baseball Hall of Fame, accessed online at https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/miller-marvin on August 31, 2021.

24 Richard Goldstein, “Marvin Miller, Union Leader Who Changed Baseball, Dies at 95,” New York Times, November 28, 2012. Accessed online at https://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/28/sports/baseball/marvin-miller-union-leader-who-changed-baseball-dies-at-95.html on August 31, 2021.

25 Miller, “A Celebration of Baseball Unionism: Remarks: Reflections on Baseball and the MLBPA.”

26 Bill Madden. “Tributes at memorial reinforce iconic status of MLBPA’s former executive director Marvin Miller,” New York Daily News, January 27, 2013. Accessed online at https://www.nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/madden-tributes-memorial-reinforce-miller-iconic-status-article-1.1248786 on August 31, 2021.

27 “Marvin Miller,” FindAGrave.com. Accessed online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/101353842/marvin-miller on August 31, 2021.

28 “Marvin Miller,” International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame. Accessed online at http://www.jewishsports.net/BioPages/MarvinMiller.htm on August 31, 2021.

29 Emma Baccellieri. “Marvin Miller Didn’t Want to Be a Hall of Famer. Now what?” Sports Illustrated, December 10, 2019. Accessed online at https://www.si.com/mlb/2019/12/10/marvin-miller-hall-of-fame on August 31, 2021.

30 Goldstein.

Full Name

Marvin Julian Miller

Born

April 14, 1917 at Brooklyn, NY (US)

Died

November 27, 2012 at New York, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.