Charlie Brown

This article was written by Frederick C. Bush

When the Chicago Cubs finally won a World Series again in 2016, after 108 years of futility, they also shed their standing as “lovable losers,” ceding that title back to the squad to whom it truly belonged: Charlie Brown and his ragtag neighborhood team of Peanuts fame. Indeed, for all the failure and ignominy the Cubs endured for more than a century, their collective collapses paled in the face of the disappointments suffered by the round-headed player-manager — whose jersey both on and off the field is his ubiquitous yellow polo shirt with the black zigzag stripe — and his band of misfits.

As his team’s pitcher, Charlie Brown is literally undressed — most often all the way down to his boxer shorts — by many a ball hit back through the middle. His second baseman, Linus, constantly trips over the security blanket that he always drags around. Lucy, Linus’ older sister and the squad’s right fielder, is possibly the worst player the game has ever seen. Schroeder, the catcher, apparently is unable to throw the ball, so he walks it back to the mound after every pitch. The best player on the team is Charlie Brown’s pet beagle, Snoopy, who plays shortstop; of course, he is unable to throw out any baserunners, although he excels in spitting the ball to Linus who makes the pivot on double plays. Charlie Brown’s team is not a “Who’s Who,” but rather is a “Who’s Not,” yet even they afford him little respect and often call him a “blockhead.”1

Although his sandlot career has been filled with disadvantages and setbacks, Charlie Brown may love baseball more than any person who has ever lived, whether in real life or in a cartoon strip. His hope springs eternal and he always looks forward to the next game in anticipation of finally tasting victory. His perseverance has made him a fan favorite of baseball aficionados in America in spite of the fact that his average is always below the Mendoza Line, his losing streak as a pitcher is longer than Anthony Young’s, and he has committed far more egregious blunders than Fred Merkle’s boner in 1908.

Charlie Brown was born on October 3, 1946, according to the Peanuts strip that ran in newspapers on November 3, 1950.2 However, there are discrepancies in regard to both his birth date and his age. On April 3, 1971, he tells Linus that he will turn 21 years old in 1984, which would make his birth year 1963.3 In regard to the debate about his age, which remains static, estimates place him at anywhere between eight and 10.

Much of Charlie Brown’s home life also remains shrouded in mystery. What is known is that his father is a barber and his mother is a homemaker. He also has a younger sister, Sally, and the aforementioned pet, Snoopy. His exact place of residence is unknown, but the climate is cold enough for there to be heavy snow in winter. Charlie Brown has been known to stand upon his snow-blanketed pitcher’s mound while dreaming of future glory, only to be rudely brought back to reality by snide comments from Lucy. In the end, all matters of time and place are irrelevant for an immortal cartoon character.

Charlie Brown, like many of his fellow Peanuts gang members, is a true renaissance kid. Over the years, he has competed in spelling bees, has been an exchange student in France, has taken part in numerous summer camps and all their attendant activities, and has competed in sports as diverse as motocross, the decathlon, and football. Perhaps Charlie Brown’s fans owe thanks to Lucy — who as his holder in football, always pulls away the ball before poor Charlie can kick it — for keeping him from further pigskin pursuits. His failure to kick a football may well be what has made him pursue baseball more ardently, even if his disappointments on the diamond have been far greater than those on the gridiron.

Truth be told, Charlie Brown’s first love is, and always has been, baseball. He developed his passion at an early age and, like every fan, he has a favorite player. While he is an admirer of all the greats, his idol is the little-known Joe Shlabotnik. When Charlie Brown finds out that Lucy has a Shlabotnik baseball card, he offers her his entire collection — including future Hall of Famers like Mickey Mantle — but she refuses to trade. A crestfallen Charlie Brown, who has been trying to get a Shlabotnik card for five years, walks away just before Lucy tosses the card in a garbage can because she decides that Shlabotnik is not as cute as she thought he was.4

In 1964, Charlie Brown finds out that Shlabotnik has been sent down to the minor-league team in Stumptown, which is part of the Green Grass League. In spite of the fact that Shlabotnik was demoted because of his .004 batting average, Charlie Brown remains optimistic that his hero will lead Stumptown to its first pennant.5 At one point, he becomes the founder of the Joe Shlabotnik fan club and publishes its newsletter. The first issue is also the last, and the fan club folds because Charlie Brown is its only member. It is not surprising that no one else idolizes a player who is perhaps best known for making spectacular catches of routine fly balls and for throwing out a runner who had fallen down between first and second base.6

On two separate occasions, Charlie Brown thinks he will get to meet his hero, only to have Shlabotnik get lost and miss both banquets. In the end, he finally catches a glimpse of Shlabotnik under the usual humiliating circumstances for both individuals. After retiring as a player, Shlabotnik takes the managerial reins for the Waffletown Syrups, but he is fired after one game for calling a squeeze play with no one on base. As Shlabotnik is leaving Waffletown, Charlie Brown catches up to his bus and hands him a baseball to autograph. When the bus begins to pull out of the station, Shlabotnik throws the ball at Charlie Brown, which hits him in the head and knocks him out. Nevertheless, he does end up with a Shlabotnik-autographed baseball.

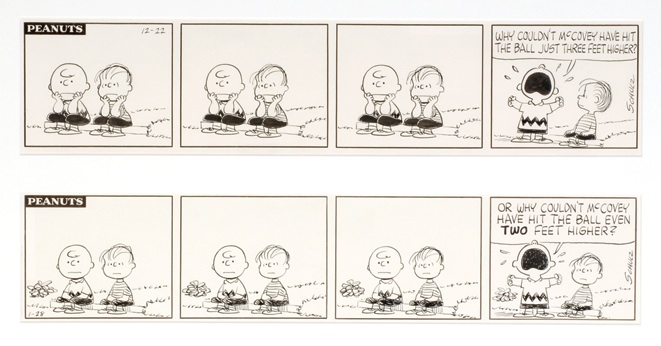

Although Charlie Brown’s favorite player is as fictional as Charlie himself, his favorite team is quite real. Peanuts creator Charles Schulz was a fan of the San Francisco Giants and two of the team’s Hall of Famers, Willie McCovey and Willie Mays, gain mention in Peanuts. In the December 22, 1962 strip, Charlie Brown and Linus are seen moping for three frames before Charlie Brown jumps up and shouts, “Why couldn’t McCovey have hit the ball just three feet higher?”7 His lament is a reference to Game Seven of the 1962 World Series between the Giants and the New York Yankees. With the Yankees leading 1-0 in the bottom of the ninth, Matty Alou was on third and Mays on second with two outs as McCovey came to bat. McCovey hit a long foul ball on the first pitch he saw and then stroked a screaming line drive straight at Yankees second baseman Bobby Richardson, who caught it at shoulder height to win the Series for New York.8

(Click image to enlarge.)

On another occasion, Charlie Brown loses a school spelling bee when he spells the word “maze” as “Mays” because he is thinking of another San Francisco Giants hero.9 Mays also has a connection to Charlie Brown’s first television special, the perennial favorite A Charlie Brown Christmas. Producer Lee Mendelson filmed a 1963 television documentary about Mays titled “A Man Named Mays.” Soon thereafter, Mendelson approached Schulz about making a Peanuts documentary. After learning that Mendelson had produced the Mays special, Schulz agreed to the idea and asked animator/director Bill Melendez to collaborate on the project. The resulting Peanuts documentary never aired on television, but Mendelson and Melendez teamed up on the 1965 Christmas special that won both Emmy and Peabody awards and then created several more acclaimed Peanuts television specials over the years.10

In fact, the second Mendelson-Melendez Peanuts production was the baseball-themed Charlie Brown’s All-Stars in 1966. Charlie Brown’s team of ragtag misfits loses its opening day game by the unfathomable score of 123-0. The entire team quits, but they are lured back when a hardware-store owner, Mr. Hennessey, offers to sponsor the team in a real league and to buy them uniforms. There is one caveat to Hennessey’s sponsorship: According to league rules, Charlie Brown cannot have girls or his dog on the team. Out of loyalty to his friends and his pet, Charlie Brown refuses the sponsorship and the uniforms; however, he is afraid that the team might quit again. His team is so excited at the prospect of having uniforms that he is certain they will win their next game. Thus, he hatches the plan not to tell them that he has declined Hennessey’s offer until they are so intoxicated by victory that they will not mind anyway.

Charlie Brown’s plan stands a chance of working as the team truly is competitive in its next game. With two men out in the bottom of the ninth, Snoopy singles and then steals second, third, and home to draw the team within one run of its opponent. Even Charlie Brown garners a rare base hit, but he overplays his hand by trying to duplicate Snoopy’s feat to tie the game and ends up being thrown out at home plate. In the aftermath of defeat, the team abandons him again when they find out there will be no uniforms. Soon afterward, Linus tells the girls on the team why Charlie Brown declined the uniforms, and they decide to make amends for their selfishness. In a gesture of goodwill, they take Linus’ security blanket and sew a jersey for Charlie Brown with “Our Manager” stitched across the front and present it to him as they rejoin the team. It is a rare sign of respect and appreciation for Charlie Brown, who once confirmed Schroeder’s assertion that he would rather manage than eat by turning down Lucy’s offer of a doughnut.

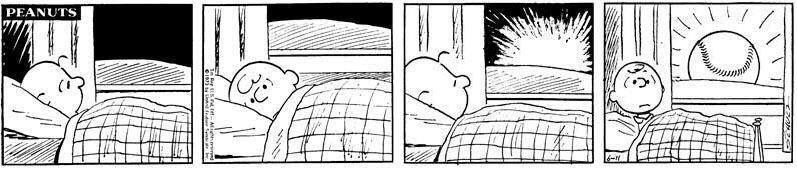

While numerous television specials have chronicled Charlie Brown’s baseball team throughout the years, the round-headed kid’s obsession with baseball comes through most clearly in a 1973 storyline that Schulz admitted “worked out far beyond my expectations. . . and [was] one of which I was proud.”11 One morning, Charlie Brown wakes up to a sun that looks like a baseball. Soon, all round objects, including such things as the moon and a scoop of ice cream, begin to look like baseballs. When Charlie Brown develops a rash on the back of his bald head that resembles the stitches on a baseball, he visits his pediatrician out of fear that he may be losing his grip on reality. By this point, he has taken to wearing a paper grocery sack over his head to cover the rash because, as he explains to his doctor, someone tried to autograph his head.12

The doctor recommends that Charlie Brown should go to summer camp to get his mind off baseball for a time. He goes grudgingly but then begins to enjoy himself after some kids elect him ‘camp president’ on a lark. Although the kids all call him “Sack,” due to him still wearing the aforementioned grocery bag, Charlie Brown earns their respect and is considered by all to be a great camp president. Eventually, his rash ceases to itch and Charlie Brown takes off his sack as he sneaks out of the bunkhouse early one morning to watch the sun rise while wondering whether or not it will still look like a baseball to him. Schulz brought this storyline to a surprising but brilliant end by having the rising sun resemble Alfred E. Neuman, the face of MAD magazine. Without his sack, Charlie Brown reverts to his old self rather than continuing to be the revered camp president.

There is a distinct possibility that Charlie Brown’s baseball-stitch rash may have been brought on by the fact that he had to forfeit his team’s first victory, which occurred in April 1973, due to a gambling scandal. Lucy convinces Charlie Brown to allow her and Linus’ new baby brother, Rerun, to join the team. Opposing pitchers are unable to hit little Rerun’s strike zone, which is far smaller than even Rickey Henderson’s was. The team rallies around Rerun, their on-base machine, and finally triumphs over an opponent; however, the taste of victory ends up being short-lived. It turns out that Rerun and Snoopy had a nickel bet on the outcome of the game which results in the win becoming a forfeit loss. Rerun’s excuse, “I didn’t know it was wrong. I’m new in the world,” was one that Pete Rose could have been proud of, even if Rose could not say the same for himself in regard to his own gambling scandal that resulted in his lifetime banishment from baseball.13

In 1976’s It’s Arbor Day, Charlie Brown, another goodwill gesture results in further distress for Charlie Brown on the baseball field. After learning about Arbor Day, the Peanuts gang becomes inspired to plant a garden in Charlie Brown’s baseball field, complete with a tree in the middle of his pitcher’s mound. Peppermint Patty, the tomboy friend and sporting rival who always calls him “Chuck,” brings her team to play the first game at Charlie Brown Field. Even though she thinks playing in a garden is an untenable situation, the game goes on as scheduled. The trees planted throughout the field catch many of the line drives and fly balls, and neither team can score for several innings.

The first run of the game is scored, surprisingly, by Lucy who has long had a crush on the catcher, Schroeder. As she heads to the plate, Lucy asks Schroeder if he will give her a kiss if she hits a home run. Schroeder readily agrees since Lucy never even makes contact with the ball. However, Lucy never had the motivation of a kiss before and she now connects for her first round-tripper. Schroeder is horrified, but he is prepared to honor his word. He is relieved when Lucy declines his kiss since she knows that he is not offering it because he likes her. Charlie Brown is simply elated that his team has the lead, but his joy does not last long because a storm soon rains out the game.

Although 1973’s gambling-marred victory and 1976’s rainout against Peppermint Patty’s team were not official victories, Charlie Brown does lead his team to two triumphs in 1993, each time by mashing a homer. In a nod to the classic baseball novel and film The Natural, Charlie Brown hits both four-baggers against a pitcher named Royanne Hobbs, whose great-grandfather was named Roy Hobbs.14 A few months later, Charlie Brown hits an inside-the-park homer on which he takes out Royanne Hobbs with a slide into home plate.15 Later in the summer, Royanne tells Charlie Brown that she let him hit both homers because she likes him. Her revelation spoils Charlie Brown’s joy in his accomplishment and he responds by telling her that Roy Hobbs is a fictional character.

Whether or not the two “Hobbs triumphs” were tainted, it makes sense that, on the heels of two victories, the topic of uniforms for Charlie Brown’s team comes to the fore again in 1996’s It’s Spring Training, Charlie Brown. Although the members of the Peanuts gang have not aged, the times have changed and having girls and a dog on the team no longer presents a problem. The team again has a shot at a sponsorship and accompanying uniforms, but they have to earn them by winning their first game. Miraculously, the team is victorious in its opener by a 27-26 score. The storyline has some distinct similarities to the one in which Rerun helps the team to its first win in 1973. This time around, the victory is due in large part to a new player named Leland, center fielder Frieda’s little brother, who is so short that he has no strike zone and is constantly being walked or beaned (thankfully, unlike most of the Peanuts characters, he wears a batting helmet). In contrast to Rerun, Leland does not engage in any gambling activity and the team gets to keep both its win and its uniforms. As it turns out, though, Leland’s new uniform is too big for him to be able to play in it — it is obviously not tailored — and he has to quit the team. After Leland’s departure, the gang returns to its losing ways.

Charlie Brown’s next attempt to reverse his team’s fortunes in 2003’s Lucy Must Be Traded, Charlie Brown involves donning the general manager’s cap. He takes the tried-and-true tactic of revamping his squad via a trade with Peppermint Patty’s team. Charlie Brown understands the truth behind the maxim that a team “has to give something in order to get something,” so he trades his best player, Snoopy, for five of Peppermint Patty’s players. The move proves unpopular with both his team and his dog, and Charlie Brown voids the trade, which is just as well since Peppermint Patty’s players say they will give up baseball before they will play for Charlie Brown’s team.

Later in the season, Charlie Brown tries a different approach by trading his worst player, Lucy, to Peppermint Patty in exchange for her friend Marcie and a pizza. Things again fail to work out as Marcie does not play — she simply stands beside Charlie Brown on the pitcher’s mound — and Lucy drives Peppermint Patty crazy with her ineptitude and fussy attitude. This trade, too, is soon voided, though Charlie Brown comes out on top in the deal because he already has eaten the pizza and does not have to buy Peppermint Patty a new one.

In the end, it is Charlie Brown’s resolve — in the face of so many failures — to try and to try again that has endeared him to millions of fans for well longer than half a century. Schulz once explained:

Charlie Brown has to be the one who suffers, because he is a caricature of the average person. Most of us are much more acquainted with losing than we are with winning. Winning is great, but it isn’t funny. While one person is a happy winner, there may be a hundred losers using funny stories to console themselves.16

Charlie Brown sometimes gets down when he loses or fails at something, but he always bounces back with renewed vigor. The result is that his string of failures makes the rare victories that come his way so much sweeter, and his determination to keep striving for those moments has turned him into an “everyman” type of hero.

(Click image to enlarge.)

Author’s note

This SABR biography of Charlie Brown is intended to be purely a baseball biography. Any attempt to write a full biography would have resulted in a book-length work and would have gone too far afield from the purpose of portraying Charlie Brown as both one of the ultimate lovers of America’s Pastime and an “everyman” to whom fellow baseball lovers can relate. Additionally, the article is not intended to be a fully comprehensive account of all of Charlie Brown’s and the Peanuts gang’s baseball exploits. (SABR member Larry Granillo’s presentation at SABR 40 covered that in fine detail.) Perhaps the most notable omission is that of Snoopy’s pursuit of Babe Ruth’s career home run record, a storyline that Charles M. Schulz created after learning of all the hate mail that Hank Aaron was receiving during his pursuit of the Bambino’s mark. The explanation for this omission is simple: It belongs in a biography of Snoopy.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Joel Barnhart and fact-checked by Warren Corbett.

Photo credits: Courtesy of Peanuts.com.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes below, the author also consulted numerous Peanuts anthologies and the DVD versions of the television specials mentioned in the biography.

Foremost among the anthologies not cited in the notes were the following:

Schulz, Charles M. Peanuts, A Golden Celebration: The Art and the Story of the World’s Best-Loved Comic Strip, Ed. David Larkin, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1999.

Schulz, Charles M., Peanuts Treasury, New York: Metro Books, 2005.

Schulz, Charles M., Who’s on First, Charlie Brown? , New York: Ballantine Books, 2004. (This anthology includes almost every baseball-themed Peanuts cartoon strip and contains an introduction written by Cal Ripken, Jr.).

Notes

1 Although there have been rare occasions on which other players briefly have joined the team, Charlie Brown’s lineup has had remarkable stability over the decades. The normal lineup is as follows: Pitcher: Charlie Brown Catcher: Schroeder First Base: Shermy Second Base: Linus Third Base: Pig Pen Shortstop: Snoopy Left Field: Violet Center Field: Patty and Frieda (perhaps a lefty-righty platoon) Right Field: Lucy

2 Peanuts, November 3, 1950, https://www.gocomics.com/peanuts/1950/11/03, accessed October 10, 2018.

3 Peanuts, April 3, 1971, https://www.gocomics.com/peanuts/1971/04/03, accessed October 10, 2018.

4 Peanuts, August 18, 1963, https://www.gocomics.com/peanuts/1963/08/18, accessed October 10, 2018.

5 Peanuts, July 30, 1964, https://www.gocomics.com/peanuts/1964/07/30, accessed October 10, 2018.

6 Peanuts, March 8, 1970, https://www.gocomics.com/peanuts/1970/03/08, accessed October 11, 2018.

7 Peanuts, December 22, 1962, https://www.gocomics.com/peanuts/1962/12/22, accessed October 10, 2018.

8 Richardson’s catch of McCovey’s liner can be seen toward the end of the brief video at this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FZ4o7PVdWFU

9 Peanuts, February 9, 1966, https://www.gocomics.com/peanuts/1966/02/09, accessed October 10, 2018.

10 Justin McGuire, “As ‘A Charlie Brown Christmas’ hits 50, don’t forget to thank Willie Mays, http://www.sportingnews.com/us/mlb/news/charlie-brown-christmas-50th-anniversary-channel-tv-willie-mays-peanuts/5x0ct1t55z3912vvtuvavljev, accessed October 10, 2018.

11 Charles M. Schulz, Peanuts Jubilee: My Life and Art with Charlie Brown and Others (New York: Ballantine Books, 1975), 166. This storyline was adapted as the “Sack” segment of 1983’s It’s An Adventure, Charlie Brown.

12 Peanuts, June 18, 1973, https://www.gocomics.com/peanuts/1973/06/18, accessed October 11, 2018.

13 Peanuts, April, 19, 1973, https://www.gocomics.com/peanuts/1973/04/19, accessed October 11, 2018.

14 Peanuts, April 1993 comic strips, http://peanuts.wikia.com/wiki/April_1993_comic_strips, accessed October 11, 2018.

15 Peanuts, July 1993 comic strips, http://peanuts.wikia.com/wiki/July_1993_comic_strips, accessed October 11, 2018.

16 Schulz, 84.