Richmond Virginias team ownership history

This article was written by Bruce Allardice

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

There was much ballyhoo when, in 1962, Major League Baseball made its long-overdue move into the Deep South by awarding an expansion franchise to Houston, Texas. This was swiftly followed by a club moving to Atlanta and by two more expansion franchises in Florida. Yet in all the ballyhoo, it was largely forgotten that Major League Baseball had penetrated the South 78 years before. That club, the Richmond Virginias1, lasted only half a season. It was a replacement club that did nothing memorable on or off the field, and was never contemplated as a permanent Southern franchise. Yet its story is worth telling.

Richmond’s Baseball Background

The genesis of the major-league team was the Virginia Base-Ball Club (VBBC), established in 1883. However, baseball already had a vibrant history in Richmond. The first baseball club was formed there in the summer of 1866. Northern transplants as well as Confederate army veterans flocked to form clubs. Historian Harrison Daniel observes that in Richmond, Virginia, alone, “(b)y the fall of 1866, at least fifteen adult and a dozen junior teams had been formed in the city.”2 By 1870, 45 different baseball clubs had formed in the “River City.” During the 1870s, baseball is said to have spread “like cholera.” This intensely Southern city wholeheartedly embraced this quasi-Northern game. Perhaps the ultimate mark of Richmond’s social acceptance of baseball came when one Richmond club made Confederate (and Virginia) icon Robert E. Lee an honorary member.3

The first semiprofessional team in Richmond formed in 1881. Shoe manufacturer Henry C. Boschen, the son of German immigrants, brought in players and paid them to play for his company team, unimaginatively named the Richmonds or the Virginians. Boschen’s team “played at the Richmond Base-Ball Park, located at the corner of Clay and Lombardy streets, opposite the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad yards. The facility eventually had a ‘beautiful grand stand with two private boxes on each end … expressly for the ladies.’” Although Boschen charged admission to his team’s games (25 cents for adults, 15 cents for children), apparently much of the money for the club’s operations came out of his own pocket. Usually, crowds of less than 1,000 turned out for their games.4

The Virginia Base-Ball Association

In June of 1883 a joint-stock company formed, the Virginia Base-Ball Association that later morphed into the big-league franchise. Local businessman William Seddon headed the new club. Within two weeks Judge Beverly Wellford (uncle of one of the directors) granted the Association a charter of incorporation. The incorporators included Seddon, a grocer and stockbroker; Charles H. Epps, the city police sergeant; insurance executives Frank Steger and Tom Alfriend; Charles Straus; George A. Smith; Felix I. Moses; Otho Owens; Charles Skinker; Valentine Hechler; S. B. Witt; and G.A. Wallace. At the subsequent election, Seddon was chosen president. The other officers were Epps as vice president, Steger as secretary, and insurance executive Alfriend as treasurer. Elected to the Board of Directors were Straus, Smith, Moses, Owens, Skinker, Hechler, Peyton Wise, Simon Sycle, Beverly Wellford, and John L. Schoolcraft. [See the Appendix for bios of the officers of the club.5

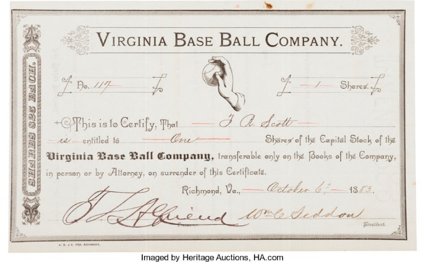

Officers of the Virginias: William Cabell Seddon (c. 1880s), courtesy Seddon Cabell Nelson. Thomas L. Alfriend, from Richmond Times, April 20, 1901. Charles H. Epps, from Richmond Daily Times, April 17, 1897. Frank Steger, from New Orleans Times Dispatch, April 1, 1897.

The board consisted of “some of the best people of all classes,” said the Richmond Virginian.6 The R.G. Dun rating company (today, Dun & Bradstreet) judged Seddon “a young man of excellent character & business habits,” Alfriend a man of “integrity & character,” and Schoolcraft a “man of fair business qualifications, good character, and steady habits.” Sporting Life believed the VBBC backers were “first class men,” “well heeled financially.”7 The board comprised a variegated mix of “First families” (Seddon, Steger, Wise, Wellford, Moses, Maury) and German-American shopkeepers, representing a cross-section of the city’s young businessmen. They were solidly upper middle class, but none of them millionaires – the club lacked the big-bucks backing of a Henry Lucas, St. Louis’s baseball magnate. Half the board members were Confederate army veterans, and perhaps not surprisingly, the VBBC often identified itself with the larger community of veterans.

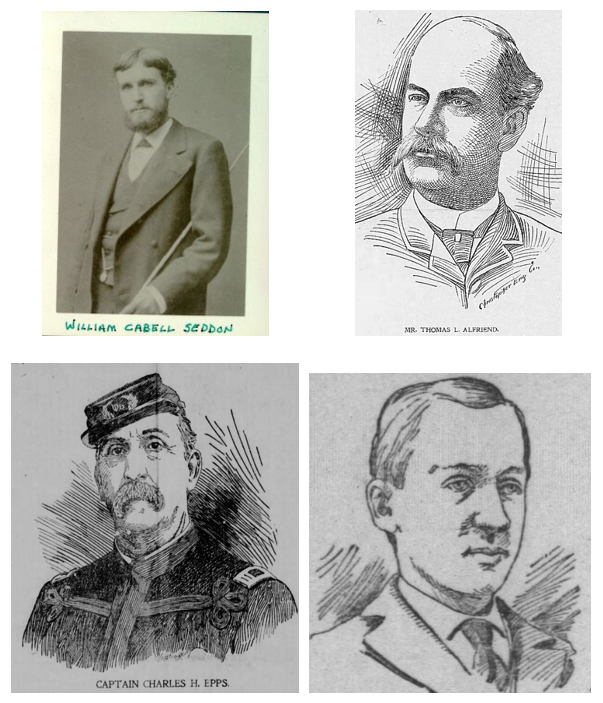

Capital stock on the amount of $5,000 to $20,000 was to be sold, though it appears only the lesser amount was realized. Shares of stock sold for $25 apiece. The VBBC quickly announced that $1,400 in stock had already been sold, and that a three-man committee was selected to find a playing field.8

The new team, officially named the Virginia Base Ball Club, lured away most of Boschen’s players.9 Perhaps the team’s best player was 20-year-old pitcher Charlie Ferguson, who went 15-8 that year. Later in the season Philadelphia of the National League paid a reported $3,000 for Ferguson, who went on to win 99 games over the next four years.10

Its uniforms featured white jerseys with “Virginia” written in red across the chest, red belts, and red stockings.11

Virginia Base Ball Company stock certificate, circa 1883. (Heritage Auctions)

Within a few days of the team’s formation, the VBBC leased grounds for a ballpark at the western edge of the city. As early as June 26, workers began putting up wooden fences, and construction was finished within a week. The grounds were at the then-western end of Franklin Street, on the Otway Allen estate, and across from Richmond College. The Lee monument once stood near the location of the main gate. The park could hold almost 3,000 spectators, and was expanded to seat more prior to the 1884 season.12

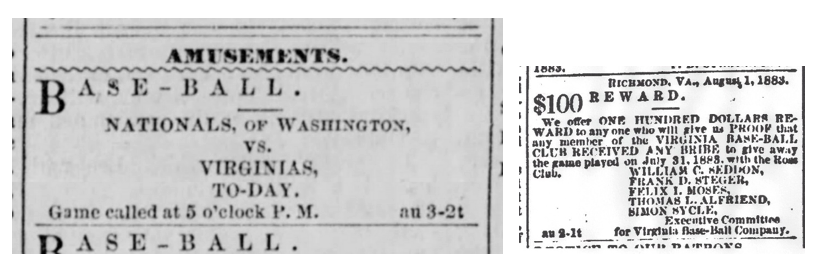

The new team, under manager E.J. Kilduff,13 played a mix of local amateur and semipro teams, games against teams in the minor-league Interstate Association (forerunner of the Eastern League), plus three games against major-league teams. It finished 33-14, with 9 of the 14 losses against the professional teams.14 Perhaps the most notable event of the season occurred in an early game after which the Richmond players were accused of taking bribes. The players heatedly denied the charges, and the club offered a $100 reward (never claimed) for evidence of cheating.15 Financially, the club had mixed success. Overall gate-receipt numbers are lacking. However, the first regular home game, against the major leagues’ Baltimore Orioles, grossed $245, while their signature home game, a 1-0 loss on October 15 to the National League champion Boston Beaneaters, grossed $486, suggesting crowds of 1,000 to 2,000 for home games against big-league opponents.16

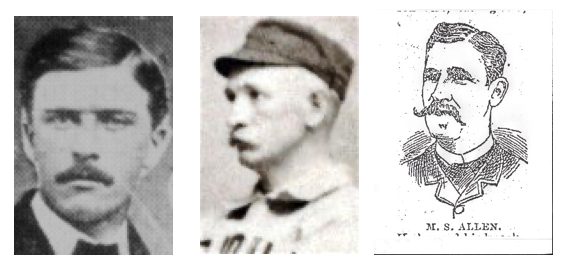

During the winter of 1883-84, Richmond made moves to strengthen its team for the coming Eastern League season. In late 1883 it reached a verbal agreement with veteran baseball man Ted Sullivan, the manager of the American Association’s St. Louis Browns, to manage the Virginias. However, in early 1884 Sullivan informed the Virginias that he was joining the Union Association’s new St. Louis franchise, the Browns owner having offered him far more pay. The club instead hired pitcher Myron S. Allen of the Kingston, New York, club to manage and pitch. Allen lasted only to midsummer, being replaced as manager by team executive Felix Moses and later by first baseman Jim Powell. Manager Allen brought with him from Kingston brothers Ed and Bill Dugan, Brooklyn natives, along with several other players.17 In many ways, the changes replaced local players with imported, Northern talent.

Ad for the Virginias, Richmond Dispatch, August 3, 1883. Reward notice, Richmond Dispatch, August 2, 1883.

The Major Leagues Beckon

In late 1883, Richmond’s potential move into an organized professional league drew media attention. A Richmond newspaper noted that for any professional team to make a profit, it needed to belong to a league. The newspaper gently (and not so subtly) hinted that “for the information of the outside world, Richmond is as liberal in its patronage of good ball-playing as any city its size in the Union, and it is believed that the Virginia Base-Ball Company would be in full accord with such a movement as the one above referred to.”18

One baseball historian has labeled 1884 “The Year Baseball Went Crazy.” In late 1883 a group of baseball men decided to challenge the two existing major leagues (the eight-team National League, established in 1876, and the newer eight-team American Association, founded in 1882). The new Union Association refused to recognize the 11-man reserve clause that the NL and AA had agreed to, believing that this grant of more freedom to the players would allow them to poach freedom-seeking talent from the two established leagues.

The UA announcement of a new league set off a series of events that, in retrospect, seem misguided. The AA, for one, hastily expanded from eight teams to 12, placing new franchises in cities such as Brooklyn and Washington in order to block the UA gaining a foothold in those cities. This vast expansion (16 franchises to 28) led to a dilution of talent among the more numerous teams, the establishment of financially weak franchises, and a dilution of ticket-buying baseball fans among the many more teams. However, the three-league war gave cities the size of Richmond a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to break into the major leagues.19

Representative baseball men of nine different cities met on September 12, 1883, in Pittsburgh to explore forming the Union Association. The Richmond club, represented by President Seddon, was one of the nine, albeit representing by far the smallest of the nine cities. At a subsequent meeting in Philadelphia, no Richmond delegate attended. Richmond was still interested in becoming a member, but leaned instead toward joining the new Eastern League, a minor league that would adhere to the NL/AA “National Agreement.” Richmond may also have been influenced by the fear that St. Louis, the “big money” franchise of the new league, would dominate the new league. At the UA’s December meeting, Richmond’s Felix Moses announced that Richmond would not join the league.20

Media speculation also linked the Virginias to the AA’s expansion plans. Sporting Life, for one, recommended that the AA include Richmond as one of its new franchises, noting that “[t]he Virginia Club, of Richmond, is the only club [being considered] which today stands upon a sound financial footing, with good organization, and it is by no means impossible that this club might be taken into the American Association” at the AA’s December 12 meeting. Comparing Richmond to Toledo, Ohio, another city under consideration, Sporting Life claimed that Richmond “is now by all odds a better baseball city. The Virginia Club has a five years lease of a splendid ground, is in the hands of first class men, and last season did much in creating quite a boom of base ball in the state.”21 Richmond’s Seddon and Moses applied for American Association membership at that December meeting. The AA turned them down,22 but promised the Richmond delegation the first chance to fill any vacancy that might occur.23

Rebuffed for the moment, Richmond joined a newly formed regional league, which today would be termed a minor league. This Union League of Professional Base-Ball Clubs, as it was originally known, soon expanded into an eight-team league, with franchises in Richmond, Baltimore, Wilmington, Reading, Newark, Trenton, Harrisburg, and Allentown. Renamed the Eastern League, it was the ancestor of the modern International League. At the January 1884 initial meeting of the new league, Richmond’s Seddon was elected president and Moses put on the board of directors.24

Early in the 1884 season, it became apparent to all three major leagues that a culling of the weaker franchises was inevitable. One of these franchises was the AA’s Washington club. The new Washington Nationals faced stiff competition from the new UA’s Washington franchise, also (and confusedly) named the Nationals. Neither league imagined that Washington could support two major-league franchises, but each league hoped that its franchise would be the survivor. Neither team won many games,25 but the American Association Nationals were arguably the worst team in the Association, and while the UA Nationals made money, the AA Nationals floundered. By early August, AA Nationals owner Lloyd Moxley, a theatrical costumer and billboard magnate, gave up the ghost. One Washington newspaper blamed the demise on the “lack of patronage, and the continued ill health of Mr. Moxley.”26 The club’s 12-51 record, with a then-record 15-game losing streak, played a large part in the declining attendance.

The Association looked for a club, any club, to pick up the remainder of Washington’s schedule. Preferably, the replacement had to be an existing club with a decent record. And so as not to disrupt the existing league schedule, it had to be located in the East, preferably near Washington. Richmond had a large enough fan base so that, potentially at least, visiting clubs like St. Louis could meet their expenses of traveling there to play. Most importantly, the club, like Charles Dickens’ Barkis, had to be “willin’.” In this narrow context, Richmond, which had signaled an interest to join the AA in late 1883, seemed a plausible choice.

The Business Context

In 1884 the thriving city of Richmond was the 25th largest city in the United States, with a population estimated locally at 75,000. Including the suburb of Manchester (which merged into Richmond in 1910), just south and across the James River, the metropolitan area population was about 82,000.27 While Richmond’s size couldn’t compare to that of the big cities (Philadelphia, Chicago, New York) that had major-league franchises, it was by no means the smallest city to be considered for one.

The 1884 season saw a frenzy of expansion in major-league baseball, with three leagues (NL, AA, and UA).28 In the context of this frenzy, it made some sense to locate (or allow) Richmond to have a franchise. Put another way, a Richmond club made more sense than a number of other cities that had franchises in 1884. Richmond had a larger population than Toledo or Columbus, both of whom lasted the season in the AA. Tiny Columbus even finished second in the Association pennant race. The UA featured a (short-lived) team in Altoona, Pennsylvania (with a population less than one-third that of Richmond). In midseason the UA granted replacement franchises in Wilmington, Delaware, and Kansas City, both smaller than Richmond.

Just considering distance and travel costs, Richmond made more sense than several other franchises. The city was 116 miles and five hours’ train travel from Washington, the location of the team it was replacing, and 158 miles from Baltimore, another baseball hub. In the American Association, St. Louis was 243 miles from Indianapolis, its nearest opponent. In the Union Association, the Kansas City replacement team, the Cowboys, was 248 miles from St. Louis, the nearest UA city. Another UA replacement franchise, St. Paul, Minnesota, was even more remote, 401 miles from Chicago.

Considering population and distance, when in mid-1884 the American Association looked for a club to continue the schedule of the dissolving Washington Nationals, Richmond could be considered a plausible replacement. So after the Nationals folded on August 2, the AA’s board met two days later to find the replacement. One story has Washington’s place being first offered to the Eastern League’s leading team, the Wilmington Quicksteps, “but the astute Manager Simmons [later manager of the Virginias] wisely declined the barren honor,” fearing that the league would contract to eight teams in the offseason and leave the replacement club in the cold. The Virginias “decided to run the risks involved for the chance of displaying in a wider field of action.”29

The Club on the Field

After several exhibition games, the first Richmond contest in the Eastern League had been played on May 1. Its last Eastern League game was played on August 4. In between, Richmond earned a 30-28 record, good for third place in the league.30

The new American Association franchise played its first game on August 5, the day after leaving the Eastern League, at home, against the Philadelphia Athletic. The Virginias lost badly, 14-0.31 In their initial five-game homestand, they won only once. President Seddon announced that he would “go north” to find better players, “which his club greatly needs, if they wish to hold their hand against the other American Association clubs.”32 He soon signed several players, adding among others outfielder Walt Goldsby of the defunct Washington team. But clearly, more help was needed.

The team realized that it needed extra money in order to hire better players and compete at this higher level. The original $5,000 capital might work for a minor-league team, but not one competing at a higher level. Richmond’s owners noted that other AA teams boasted $15,000 to $60,000 in stock.33 The UA Chicago franchise was capitalized at $20,000, and the UA St. Louis franchise reportedly spent $8,500 on its grandstand. The yearly salaries of the AA clubs averaged over $20,000.34 A week after joining the AA, the team decided to sell another $5,000 in stock (doubling the capital investment) in order to pay for the talent.35

One baseball historian has estimated that in 1884, a professional team had to average 1,300 paying fans per game in order to break even.36 While attendance numbers for 1884 are spotty at best, the Richmond team clearly didn’t come close to that number at home. While the initial home games drew an average of 1,500 fans,37 the later newspaper reports tell the story. Just for October, 1884, the home games drew on average less than 600 spectators.38

Historian Robert Gudmestad analyzed Richmond attendance based on the fragmentary newspaper accounts. In 1883, for the nine home games (out of 36) with reported attendance, the Virginias averaged crowds of 1,700. He cautioned that attendance reports usually exaggerated the numbers; that this was a count of total, not paying, spectators; and that newspapers tended to report only the bigger crowds. For the Eastern League half of 1884, based on reports from 14 of 30 home games, the reported attendance was 1,600 per game. Reports from 17 (of 23) American Association home games that year placed average attendance at a little more than 1,000 per game. Clearly, the home-game revenue was insufficient to make the team profitable. The similar analysis for 1885 and the Eastern League had them drawing 1,100 fans per game.39

What profit (or loss) the Virginias made in 1884 cannot be determined, as exact records are lacking. However, one newspaper (the New York Dispatch) published what were probably wildly over-estimated American Association club profits, with the league as a whole “about $130,000 ahead,” and with Richmond ending with a $1,000 profit. Even here, Richmond’s asserted profits compared badly to those of the other AA clubs.40 After the 1885 season, one newspaper article estimated that the club was $8,000 in the red.41

The Virginias finished the (half) season with a record of 12 wins, 30 losses, and 4 ties: not very good, but much better than the awful club it replaced. The Virginias were a young team, the ballplayers averaging 24.1 years of age, with only five of the 19 players native Southerners. They scored 194 runs, versus 294 given up. Home field didn’t seem to result in an edge for them: they were worse at home (5-15) than on the road (7-15). They were not the worst team in the American Association: Their record was better than that of the Washington club they replaced, and at 12-30 they were better than Indianapolis and Pittsburgh, two clubs that started and finished the season. The Virginias were competitive (8-9) against the sub-.500 teams in the Association, but a woeful 4-21 against the better teams.42

With the club’s money woes and poor on- field record, the AA dropped Richmond (to no one’s surprise – the move had long been rumored) at the Association’s December 10, 1884, meeting. President Seddon and Secretary Moses objected, mostly because they had paid advance money for the players for next season, money that would be lost by the change. The Indianapolis franchise was also dropped, and with the prior collapse of the Toledo and Columbus AA franchises, the Association returned to an eight-club league.43 Soon thereafter, Seddon moved to Baltimore and resigned as club president, replaced by club treasurer Tom Alfriend.

The money woes extended into 1885, after the club rejoined the Eastern League. The team brought in a well-respected manager, Wilmington’s Joe Simmons,44 and the team competed for the Eastern League pennant. By midseason, the club that couldn’t match the big leaguers was proving too much for its Eastern League opponents. In July, it boasted a 46-11 record and a nine-game lead over second-place Washington. However, the new talent had come at a price: The salaries of the manager and players amounted to $1,800 per month, outstripping the gate receipts.45 In August the team, despite the on-field success, issued a call for $1,500 in subscriptions in order to get it through the remainder of the year. The drive netted only one-third of the target, and a few weeks later President Alfriend reluctantly sold two of the team’s best players, third baseman Billy Nash and outfielder Dick Johnston, to Boston for $1,250. Both went on to have long major-league careers. The sale of its best players ruined Richmond’s chances to take the league pennant. Alfriend sounded almost wistful about the fans, complaining that in 1884, when the team was losing, they told him they didn’t come out because “[t]he Virginias can’t win,” whereas in 1885 they also didn’t attend, complaining that the Virginias were sure to win.46

An embarrassing moment for the club came when its cashier, Thomas W. Carpenter, fled Richmond after embezzling $38,000 from his brokerage business. Carpenter was the bookkeeper for the brokerage of club director J.L. Schoolcraft, and stole the money to cover stock market losses. He returned from Canada two weeks later, guilt-ridden, and tried to give back the money. Later that year Carpenter pleaded guilty and was sentenced to a year in jail. There is no indication that he took any club funds, yet the episode must have damaged its image.47

After a September 18 game against Bridgeport, the Virginia players, who had not been paid for a month, met with management and threated to quit. However, with “the League pennant almost within their grasp,” the players soon changed their mind and decided to play out the remainder of the schedule, but with the players in charge, not the management.48 The club’s management “tendered the treasury to the players. The feeble sum amounted to roughly $7.50 per man. While pride propelled the players to want to finish the season and compete for the pennant, the fans did not support their efforts. About 250 to 300 spectators came out for the Virginias’ first game without management. Only 200 came to the ballpark the following day. After that game, two of the Virginias’ players accepted offers to join the Newark Club and left on the evening train.49 The club, in essence, disbanded. A few days later, the Eastern League expelled Richmond for nonpayment of dues and for failure to pay visiting clubs their guarantee.50 The 1885 Virginias finished with a 67-26 record, a close second to the Washington Nationals.51 For their part, the VBBC’s board members assumed the club’s $3,000 liabilities, each member being assessed $300 or more.52

The Eastern League itself disbanded two years later.

Conclusion

On and off the field, the Richmond Virginians did about as well as one could expect from a minor-league club that’s suddenly, in midseason, elevated into the major leagues. It lacked major-league-caliber players, major-league facilities and major-league financing, and given its known “replacement” status, couldn’t expect a long enough future to build up any of these. Its brief existence underlines the chaos that plagued baseball’s major leagues in the 1880s.

Appendix – Biographies53

President: William Cabell Seddon (1851-1923), a merchant and son of the Confederate secretary of war. In 1883 his income was $2,400, and he owned over $13,000 in personal property. Seddon would later move to Baltimore and become a prominent broker and banker there. Upon leaving, he resigned his post of president, to be succeeded by Thomas Alfriend.

Vice President: Charles Henry Epps (1840-97), sergeant of the Richmond police.

Secretary: Francis Dean Steger (1849-97), an insurance agent. Secretary of the Mutual Assurance Society. In August 1884 Jourdan Woolfolk Maury was elected secretary to replace Steger. In 1897 it was discovered that Steger had embezzled $35,000 in order to pay off his gambling debts, and he killed himself.

Treasurer: Thomas Lee Alfriend (1843-1901), an insurance agent. Owned $5,100 in real property in 1883. Elected president Dec. 20, 1884, to succeed Seddon. When Alfriend was elevated to president, Jourdan Woolfolk Maury Jr. (1856-86), a clerk in his father’s brokerage business, was chosen to succeed him, holding both the secretary and treasurer positions. Maury had been captain of Richmond’s Olympic Base Ball Club in 1874.

Board of Directors:

- Felix Inglesby Moses (1852-89), cousin of a South Carolina governor. Owned $3,000 in real property in 1883. A fertilizer dealer.

- Peyton Wise (1838-97) was the nephew of Virginia’s Governor Henry Wise. A lieutenant colonel in the Confederate army. Postwar Richmond merchant, and active in Confederate veteran affairs. His brother married the sister of Otway Slaughter Allen, the owner of the land on which VBBC’s ballpark was built.

- Beverly Randolph Wellford (1855-1936), a lawyer and member of a very wealthy family. In 1870 his property was valued at $35,000 (an inheritance) and his immediate family owned over $300,000 in real and personal property. His brother-in-law, Otway Allen, owned the land on which the ballpark was built. Later a judge, he married William Cabell Seddon’s cousin.

- Charles Robert Skinker (1839-1903), a grocer and tobacco merchant. Owned $31,900 in real property in 1883. Later a director of the Citizens Bank of Richmond, along with Wellford and Alfriend.

- Simon Sycle (1847-1906), a German-born dry-goods merchant and clothier. Owned $4,015 in real property in 1883.

- Charles Emanuel Straus (1853-1904), a clothier. Owned $2,980 in real property in 1883.

- George Alvin Smith (1844-1908), head of a firm supplying machinery and railroad supplies. Owned $1,300 in real property in 1883.

- John Lawrence Schoolcraft (1856-alive in 1913), a New York-born stock broker. Son of a US congressman. Secretary of the City Stock Exchange. In 1883 his income was $5,600, and he owned $31,000 in property. He later discovered that his wife (daughter of his business partner) had cheated on him, and, broken-hearted, he cashed in his property and fled west. Last seen in Chicago in 1896. Said to be alive when his brother died in 1913.

- Otho Otis Owens (1849-1906), a druggist. Later on the board of several banks.

- Valentine Hechler (1839-1926), a German-born pork packer. Owned $1,980 in real property in 1883.

Later directors included Wilson Miles Cary (1843-1919), merchant, and Stephen Adolphus Ellison (1835-89), tobacco manufacturer, who owned $27,532 in real property in 1883.

Incorporators in 1883. Most of the above men, and:

- Samuel Brown Witt (1850-1912), Richmond district attorney.

- Gustavus Adolphus Wallace (1829-1916), a merchandise broker. Owned $720 in real property in 1883.

- In addition, James T. Ferriter (1843-1902) was engaged to sell corporation stock. A Massachusetts-born Confederate veteran and restaurant owner.

Managers

- Joseph S. Simmons (1845-1901), manager of the Virginias in 1885. Veteran major-league player, and manager of the UA’s Wilmington Quicksteps in 1884.

- James Edwin Powell (1855-1929), player-manager of the AA Virginias in late 1884.

- Myron Smith Allen (1854-1924), who left the Richmond team early in 1884 after an injury.

Simmons and Powell images from Baseball-Reference.com. Allen from the Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 27, 1887.

Sources for Further Reading

Blake, Ben W. “Uncovering a Diamond: A Major League Club on Park Avenue,” Richmond Times Dispatch, August 9, 1981: B2.

Daniel, W. Harrison, and Scott Mayer. Baseball and Richmond: A History of the Professional Game, 1884-2000 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2015).

Gudmestad, Robert. “Richmond AA Franchise History”; Peggy Simmer, Edward Simmer, and Walter Kephart (compilers), “1884 Richmond AA.” SABR “American Association” project, at https://sabr.app.box.com/s/s7ttowtjgaep5llrtjst.

Gudmestad, Robert. “Baseball, the Lost Cause, and the New South in Richmond, Virginia, 1883-1890,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (Summer, 1998), 267-300.

Mayer, Scott P. “The First Fifty Years of Professional Baseball in Richmond, Virginia: 1883-1932” (Master’s Thesis, U. of Richmond, 2001),

Notes

1 Also nicknamed the Virginians in some sources.

2 W. Harrison Daniel and Scott Mayer, Baseball and Richmond: A History of the Professional Game, 1884-2000 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2015), 3.

3 See www.protoball.org for the clubs. “Cholera” quote from Ron Pomfrey, Baseball in Richmond (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia, 2008), 7. For Lee, see William A. Christian, Richmond: Her Past and Present (Richmond: L.J. Jenkins, 1912), 417.

4 Robert Gudmestad, “Baseball, the Lost Cause, and the New South in Richmond, Virginia, 1883-1890,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (Summer, 1998), 272.

5 Peggy Simmer, Edward Simmer, and Walter Kephart (compilers), “1884 Richmond AA.” SABR “American Association” project, at https://sabr.app.box.com/s/s7ttowtjgaep5llrtjst, 3.

6 “The Base-Ball Business,” Richmond Dispatch, June 24, 1883: 1.

7 Gudmestad, “Baseball, the Lost Cause, and the New South,” 279; “Richmond or Toledo,” Sporting Life, December 12, 1883: 2.

8 “Virginia Base-Ball Association,” Richmond Dispatch, June 21, 1883: 2. Gudmestad, “Baseball, the Lost Cause, and the New South,” 270-272.

9 Boschen scraped together a new team, which played through 1885.

10 Scott P. Mayer, “The First Fifty Years of Professional Baseball in Richmond, Virginia: 1883-1932” (Master’s Thesis, U. of Richmond, 2001), 17. Statistics from Baseball-Reference.com.

11 Simmer, “1884 Richmond AA,” 5.

12 The lot was approximately 400 feet square, at the northwest corner of Lombardy and Park. See Gudmestad’s “Richmond AA Franchise History” at SABR; “Base-Ball,” Richmond Dispatch, July 17, 1883: 4; Gudmestad, “Baseball, the Lost Cause, and the New South,” 279-80; Ben W. Blake, “Uncovering a Diamond: A Major League Club on Park Avenue,” Richmond Times Dispatch, August 9, 1981: B2.

13 Edward J. Kilduff (1859-1916), Massachusetts-born grain dealer and local amateur ballplayer.

14 “Our Base Ballists,” Richmond Dispatch, October 28, 1883: 1. For 1883-85 player statistics, See Gudmestad, “Richmond AA Franchise History,” 54-57.

15 “Many Mysterious Muffs,” Richmond Dispatch, August 2, 1883: 1.

16 E.R. Chesterman, “Ball in Other Days,” Richmond Dispatch, September 16, 1894: 1.

17 Mayer, “The First Fifty Years,” 24-25. Simmer, “1884 Richmond AA,” 8-9.

18 “Base-Ball,” Richmond Dispatch, September 4, 1883: 1.

19 Justin McKinney, “A Season on the Brink: A Financial Summary of the Union Association in 1884,” Base Ball, 11 (2019): 167-191. See also David Nemec, The Beer and Whisky League (Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, 1994), for more on the AA.

20 See Barney Terrell, “1883-84 Winter Meetings: The Union Association,” in Jeremy Hodges and Bill Nowlin, eds., Base Ball’s 19th Century ‘Winter’ Meetings, 1857-1900 (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2018). See also Richard Hershberger, “The First Baseball War: The American Association and the National League,” Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2020: 115-125.

21 “Base Ball,” Sporting Life, December 12, 1883: 2; “Richmond or Toledo,” Sporting Life, December 12, 1883: 2.

22 “Base Ball,” Sporting Life, December 19, 1883: 2.

23 “The American Association Convention,” New York Clipper, December 22, 1883: 672.

24 “Base Ball,” Sporting Life, January 9, 1884: 2. The Eastern League formed largely from the 1883 Inter-State Association.

25 The UA Nationals finished 47-65, while the AA Nationals went a horrid 12-51.

26 “The Washington Club Disbanded,” Washington Evening Star, August 4, 1884: 4.

27 Chataigne’s 1883 Richmond City Directory (online at www.ancestry.com) estimated the city’s population at 75,000. The 1880 US Census found 63,600 residents (40 percent African-American), and a police census the same year found 71,000 residents. The 1890 census suggests Richmond’s population was growing by 2,000 each year. Manchester had 5,720 residents in 1880.

28 With teams going bust and being replaced, there were 33 different major-league teams that year.

29 “Sports and Pastimes,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 10, 1884: 4. “Games Played Aug. 5,” Sporting Life, August 13, 1884: 4. Wilmington had fewer residents than Richmond, but it had a better team (the Quicksteps were dominating the Eastern League) and was geographically closer to the other American Association clubs.

30 Simmer, “1884 Richmond AA,” 4-6; “The Virginias vs. The Harrisburg Club,” Richmond Dispatch, May 2, 1884: 1. Different accounts have slightly different team records, according to whether games should be counted against teams that had folded in midseason. The Eastern League formally expelled the Richmond club after it joined the AA, ostensibly for not paying its dues. See Mayer, “The First Fifty Years,” 29-30.

31 See the game report in Sporting Life, August 13, 1884: 4.

32 Simmer, “1884 Richmond AA,” 6.

33 Simmer, “1884 Richmond AA,” 8-9. “Base Ball in Virginia,” Sporting Life, Aug. 20, 1884: 3.

34 McKinney, “A Season on the Brink.”

35 Simmer, “1884 Richmond AA,” 8-9.

36 McKinney, “A Season on the Brink.” Another analysis, for 1876, comes up with a similar break-even number. See Bruce Allardice, “The Chicago White Stockings of 1876: Baseball’s Most Profitable Club,” SABR Business of Baseball Newsletter, December 2019.

37 Simmer, “1884 Richmond AA,” 7-9.

38 Simmer, “1884 Richmond AA,” 21-24.

39 Gudmestad, “Richmond AA History,” 46-48.

40 “Base Ball Notes,” New York Dispatch, October 12, 1884: 8. According to the Dispatch, only two AA clubs (Indianapolis and Toledo) showed a loss. Other contemporary accounts (e.g., “The Past Professional Season,” New York Clipper, February 28, 1885: 796) suggest that most AA clubs lost money that season.

41 E.R. Chesterman, “Ball in Other Days,” Richmond Dispatch, September 16, 1894: 1.

42 Statistics from Baseball-Reference.com. The club also played several exhibition games.

43 The convention was widely reported. See “Base-Ball,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 11, 1884: 2; “Sports and Pastimes,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 12, 1884: 1; “A Great Gathering,” Sporting Life, December 17, 1884: 3. The reduction to eight clubs had long been planned. See “Baseball,” New York Dispatch, October 26, 1884: 5, and “The National Game,” Buffalo Commercial, November 11, 1884: 3.

44 “A Great Gathering,” Sporting Life, Dec. 17, 1884: 3; “From Richmond,” Sporting Life, December 31, 1884: 4.

45 E.R. Chesterman, “Ball in Other Days,” Richmond Dispatch, September 16, 1894: 1.

46 “Virginia Base-Ball Club – Meeting of Directors,” Richmond Dispatch, August 8, 1885: 1; “Nash and Johnson [sic] Released,” Richmond Dispatch, August 22, 1885: 1.

47 See various reports in the Richmond Dispatch, August 6-11, 1885; “A Repentant Thief Sentenced,” New York Times, September 23, 1885: 1.

48 Simmer, “1884 Richmond AA,” 29.

49 Mayer, “The First Fifty Years”; Simmer, “1884 Richmond AA,” 29-30.

50 “Drift From the Ball Field,” New Haven Morning Journal and Courier, September 23, 1885: 3.

51 “The Base Ball Record,” Alexandria (Virginia) Gazette, October 12, 1885: 2. Sources differ slightly on the final Eastern League won-lost records.

52 E.R. Chesterman, “Ball in Other Days,” Richmond Dispatch, September 16, 1894: 1.

53 The sources used for the bios are too numerous to list separately. Ancestry.com, familysearch.org, Richmond Tax lists, online newspapers, city directories, and more were used.