Seattle Mariners team ownership history

This article was written by Steve Friedman

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

Ken Griffey Jr. slides in with the winning run for the Seattle Mariners on Edgar Martinez’s 11th-inning double to beat the New York Yankees 6-5 in Game Five of the American League Division Series on October 8, 1995. The excitement of the Mariners’ first playoff appearance helped fuel a political effort to build a new stadium, Safeco Field, and keep the Mariners in Seattle into the 21st century. (Courtesy of MLB.com)

In many ways, the Seattle Mariners history begins on April 1, 1970, when federal bankruptcy referee Sidney Volinn declared the expansion Seattle Pilots insolvent. It was just six days before Opening Day, but the decision cleared the way for the club to relocate to Milwaukee, with an ownership group headed by a car dealer, Bud Selig.

A few months before the Pilots departed, after correctly assessing Seattle’s baseball situation as dire, the state’s attorney general, Slade Gorton, and King County Executive John Spellman asked Seattle attorney William Dwyer if he would represent the state and the county in making a legal effort to keep the Pilots in Seattle.1

Dwyer’s case was filed in the fall of 1970. He argued that a contract had been created between the American League, on one side, and the state, county and city — in effect, the people — on the other, and his contention that the American League had violated it. He alleged breach of contract, fraud and antitrust violations, even though baseball was exempt from prosecution under antitrust law.

Dwyer argued that the “implied contract” called for the American League to place an expansion franchise in Seattle and keep it there. In return, citizens, through the government, would spend money to repair an aging Sicks Stadium for the team’s temporary use and also support a $40 million bond issue to fund a domed stadium.

The case didn’t get to trial until January of 1976 because it was continued a number of times in order to give the American League and Washington state’s government entities an opportunity to reach a settlement with the aim of securing for Seattle a new major-league team.

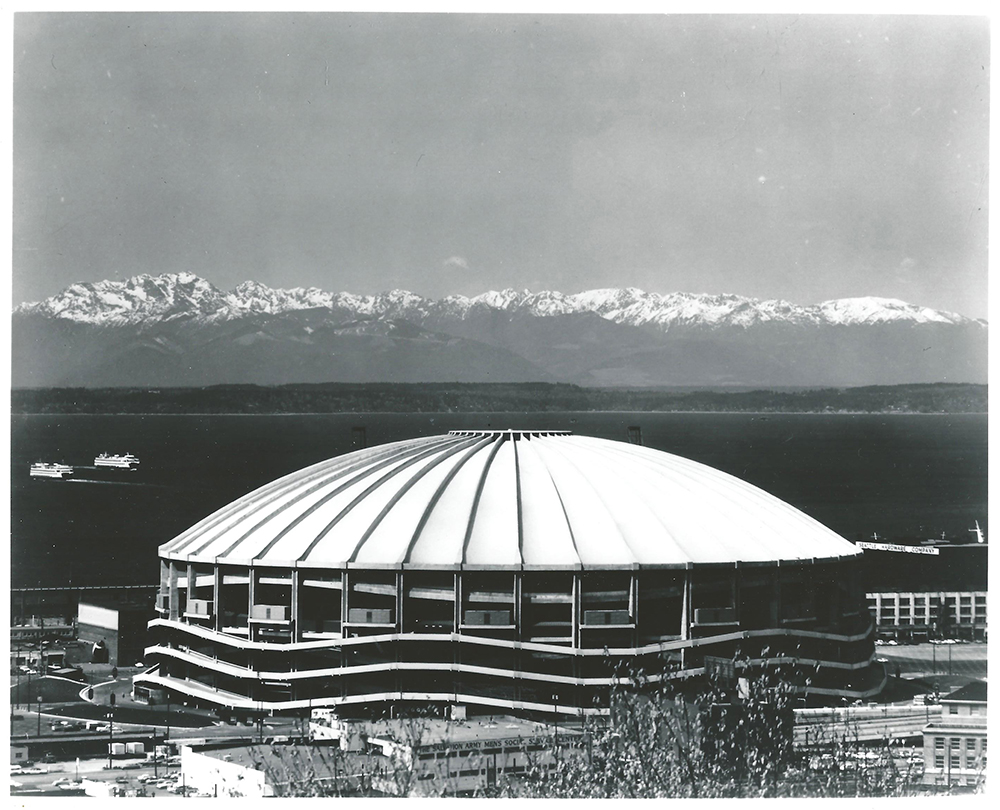

Confident that major-league baseball would return to Seattle within a few years, King County built the multipurpose Kingdome, which would become home to the NFL‘s expansion Seattle Seahawks in 1976.

At trial, the American League offered to give Seattle an expansion baseball franchise in return for dropping the suit, and details were ironed out over the next year. To keep the league with an even number of teams, a formal expansion proceeding was held, with a second team, the Blue Jays, being awarded to the city of Toronto (also allowing both leagues to have a team in Canada, the National League‘s Montreal Expos having been established in 1969).2

The expansion vote by the American League, conducted in advance of any settlement, was held on January 14, 1976. American League owners voted 11 to 1 to place an expansion franchise in Seattle for the 1977 season provided that owners could be found and that the city provide a suitable ballpark.

On February 6, satisfied with the Kingdome as a suitable baseball facility, the AL awarded an expansion franchise to a group headed by Seattle businessman Lester Smith and entertainer Danny Kaye. Other partners included Walter Schoenfeld, Steven Golub, Jim Walsh, and Jim Stillwell. The partners paid $5.53 million for the franchise.

The formal settlement of the case, however, was not reached until February 14, as the Seattle legal team argued that the plaintiffs were entitled to damages, including reimbursement of legal fees. Considering the success of Dwyer in presenting his case and the overall damages the American League faced if it lost, the league on February 14 agreed to pay damages to the State of Washington, King County and the City of Seattle. It marked the first time that a major-league franchise had been secured through litigation.3

American League President Leland S. MacPhail (left) awards the Seattle Mariners’ charter to co-owners Danny Kaye (center) and Lester Smith. In addition to being a Hollywood star, Kaye co-owned a California-based radio network with Smith. (Courtesy of David S. Eskenazi)

Initial Ownership

When Seattle was awarded the new baseball franchise in 1976, the investor group financed the team for $6.5 million, giving the team some initial working capital beyond the franchise fee.4 Lester Smith had built a radio-station group with business partner Danny Kaye, the Hollywood entertainer. The business was known as Kaye-Smith Enterprises and also included a concert-promotion company (Concerts West), a recording studio and film-production company (Kaye-Smith Productions, and a radio syndication company).5

Other owners included Stanley Golub, a local jewelry wholesaler; Walter Schoenfeld, founder of the designer jeans company Brittania Sportswear and a founding partner of the Seattle Supersonics and soccer’s original Seattle Sounders; and James Stillwell, owner of Stillwell Construction, which was active in highway construction in the Pacific Northwest.

The formation of the Seattle Mariners was the beginning of a franchise whose general lack of success on the field has not necessarily matched its historical accomplishments. Despite never making a World Series appearance, and despite a long-term losing record, this franchise has generated interest beyond its accomplishments on the field. From unique plays to special players to a few exceptional seasons, the Mariners have earned attention beyond their on-field success, or lack thereof.

During the early years, the fans’ image of the team centered on poor play and odd ownership decisions that invariably kept the team downtrodden. In those days, player moves were often made to make a brief boost in attendance or to save money, without always trying to improve the performance of the team. Starting with the ownership of Jeff Smulyan and then onto the Nintendo-based and local ownership groups, the team evolved into a community-based asset with many successful players.

The original ownership group set about creating its initial management team in preparation for its first season, to begin in April 1977. Their first move came on April 18, 1976, when the Mariners named Lou Gorman, then an assistant general manager with the Kansas City Royals, as their first director of baseball operations. Gorman’s roles with Kansas City were numerous and his initial position with them was in 1968, when he was named their first scouting director. Gorman brought to the Mariners experience in building an organization from scratch.6

On June 2 the Mariners named Dick Vertlieb, instrumental in the early development of the NBA’s Seattle SuperSonics and NFL’s Seattle Seahawks, as the club’s first executive director, or general manager.

At this time, the team still lacked a nickname, which was solved on August 24, 1976, when the team selected “Mariners” as the winning entry among the more than 600 suggestions in a name-the-team contest. Multiple fans submitted the nickname, but the team determined that Roger Szmodis of Bellevue, Washington, provided the best reason. “I’ve selected Mariners because of the natural association between the sea and Seattle and her people, who have been challenged and rewarded by it,” said Szmodis, who received two season tickets and an all-expenses-paid trip to an American League city on the West Coast.7

With their executive team hired and a team name selected, the club began to prepare to field a team. On September 3, 1976, they selected Darrell Johnson as their first manager from a candidate pool that included Bob Lemon, Joe Altobelli, and Vern Rapp. Johnson had most recently been the manager of the Boston Red Sox, fired after 86 games of the 1976 season. His real success, however, was the season before, when he led the Red Sox to the pennant and skippered the team through the exciting seven-game World Series against the Cincinnati Reds and was named the Manager of the Year by The Sporting News.

The key day to building a team was November 5, 1976, when the Mariners and the Toronto Blue Jays, the two teams set to begin play in 1977, had their expansion draft. Each team drafted 30 players from the other American League clubs, paying a fee of $175,000 for each player drafted (the fee was included in the amount of the expansion fee described above). Existing American League teams were allowed to protect 15 players in the first round, plus three more after each of the first three rounds (and two more players after the fourth round).8 With their first pick, the Mariners selected outfielder Ruppert Jones of Kansas City.

Spring training was conducted in Tempe, Arizona, and games were played at Tempe Diablo Stadium. This was the same site that the Seattle Pilots used in 1969 and 1970, prior to their move to Milwaukee. It remained the Mariners’ site through 1993, when they moved to a shared site in Peoria, Arizona.

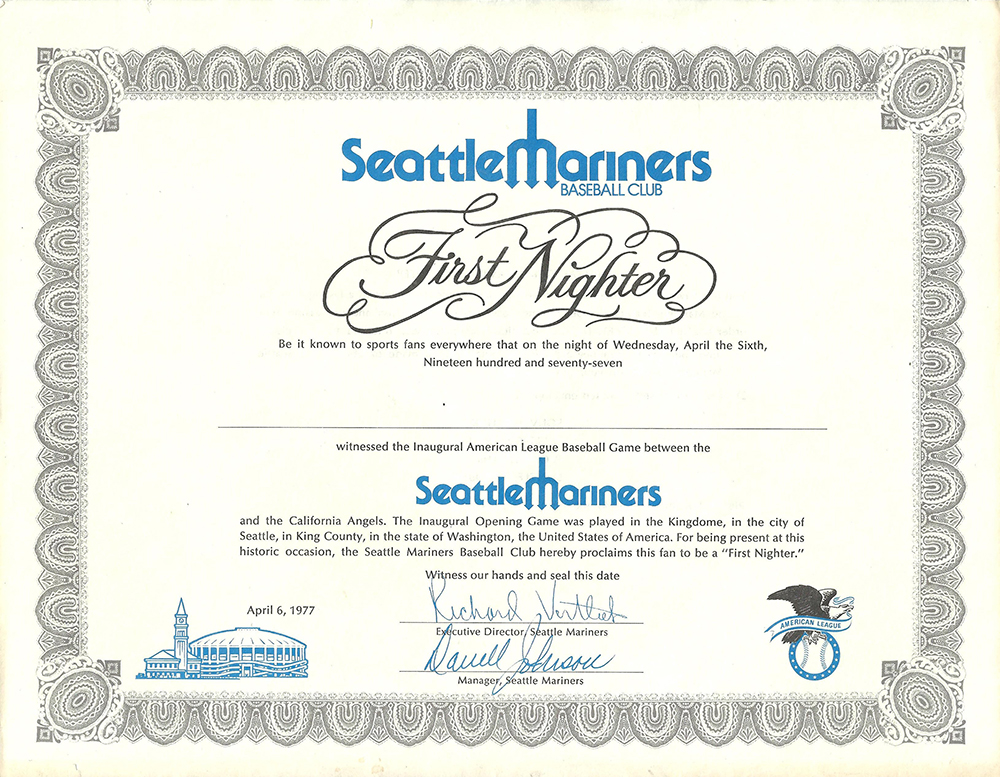

On April 6, 1977, the new Seattle Mariners played their inaugural game, against the California Angels. It was played in the Kingdome in front of a sold-out crowd of 57,762. Seattle’s starting pitcher, Diego Segui, was the only player to play for both the Seattle Pilots and the Seattle Mariners. (He had pitched the ninth (and final) inning of what would be the final game in Seattle Pilots history.9) Segui allowed six runs in the first 3⅔ innings, and the Mariners went on to lose 7-0, the mirror image of the Pilots’ home-debut win against Chicago eight years earlier. It wasn’t often pretty, but it was major league baseball.

The Mariners, as an expansion team, struggled in their early years to build a successful team. After a relatively successful first year at the gate, attendance dwindled each year under the initial ownership group and never topped 900,000 after the first year. By the end of 1980, the team was cash-strapped and weary. While accepting a 1981 award from the National Conference of Christians and Jews, Stanley Golub, then a member of ownership, quipped, “When Danny Kaye and Lester Smith came to ask me to become involved in the Mariners, they said it would be a new chapter in my life. Little did I know it would be Chapter 11.”10

In 1979, in an effort to boost interest in baseball in Seattle, the All-Star Game was hosted in the Kingdome. Bruce Bochte was the Mariners’ sole representative and he entered the game in the sixth as a pinch-hitter, singling in a run. The game was a seesaw affair, with the game’s MVP, Dave Parker, throwing out two runners from right field. In the ninth inning, the National League scored the go-ahead run and held on to win 7-6. The thrilling event did not translate into greater fan interest; the team continued to struggle to win consistently.

A ‘First Nighter’ certificate from the Seattle Mariners’ inaugural game at the Kingdome on April 6, 1977. A sellout crowd of 57,762 watched as the Mariners behind Diego Segui lost 7-0 to Frank Tanana and the California Angels. (Courtesy of David S. Eskenazi)

George Argyros

On January 14, 1981, Southern California real-estate developer George Argyros agreed to purchase 90 percent of the Mariners for $10.2 million. (He subsequently bought the other 10 percent for $2.9 million.) Argyros assumed the Kingdome lease after negotiating a provision that removed his personal liability for bankruptcy.11

During his ownership, Argyros refused to put money into the franchise and constantly threatened to move the Mariners elsewhere. He famously tried to get the front office to draft Mike Harkey over Ken Griffey Jr. in 1987. Argyros hired executives from his other industries to run the team and one offseason gave his players pay cuts and suggested they attend seminars on the value of positive thinking.12

In late 1981 there was a rumor that Argyros was attempting to unload the team he had bought less than a year before.13 While he denied this, he began continual complaints about the Kingdome, its lease, and the lack of revenue sources that would allow him to field more competitive teams, all ultimately using threats of relocation.

In 1985, Argyros denied a report that the team might move or declare bankruptcy. The report suggested that the team was looking at possible bankruptcy or a move to another city unless attendance increased and the club got a better deal for use of the Kingdome.14

In 1985, Argyros denied a report that the team might move or declare bankruptcy. The report suggested that the team was looking at possible bankruptcy or a move to another city unless attendance increased and the club got a better deal for use of the Kingdome.14

On March 26, 1987, Argyros announced he had offered to buy the San Diego Padres and that it has been accepted subject to “a final definitive agreement” and league approval. He said he wanted to sell the Mariners “as soon as possible.” This announcement shocked baseball and enraged Seattle fans. His relations with the city, county, and fan base deteriorated even further. Jim Street of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer wrote that San Diego was “about the luckiest city since Beirut.”15

Immediately after the announcement, the city and the county began to study plans to keep the team in Seattle. On April 10, 1987, Governor Booth Gardner signed a law allowing Seattle or King County to buy the Mariners as a last resort. On that same day, Baseball Commissioner Peter Ueberroth ordered Argyros to remove himself from the club’s day-to-day operations.

On May 13, 1987, Bruce Engel, a Portland, Oregon, attorney and lumber-company owner, said he’d made a $37 million offer for the team, but had been rejected by Argyros. Engel said his offer was contingent on significant minority participation from the Seattle business community. He said he would have kept the team in Seattle.16 Argyros held on.

Finally, on August 22, 1989, Argyros announced that he would sell the team to Indianapolis broadcast executives Jeff Smulyan and Michael Browning for $76 million, nearly six times what he had paid in 1981.

Jeff Smulyan

When Smulyan bought the Mariners, he was asked if, at $76 million, he had overpaid. “People say it’s the Greater Fool Theory, but we looked at the revenues and we had an idea of what we’d have to pay,” he replied. But he added: “I don’t know if the price was as much science as it was instinct.” In other words, he really wanted it.17

Smulyan had founded Emmis Broadcasting in 1979 and served as chairman and CEO since 1981. Emmis had pioneered a hugely successful new format with WFAN, New York, the nation’s first 24/7 sports radio station.

Smulyan was a baseball fanatic, and he became a quasi-hero in Seattle for buying the team from the unpopular George Argyros. However, Smulyan couldn’t overcome the challenge of making a professional team financially viable in a smaller media market. While he was more amiable to the community and marketing was focused, he lacked the deep financial pockets necessary to build a more competitive team. His optimism that he could make baseball successful in Seattle was undercut by two financial reversals. First, he had believed that the financial penalty from the collusion lawsuits filed by the players union would be no more than $1 million. The actual penalty was $10.77 million. Second, payroll skyrocketed from $8 million, when he purchased the team, to $23 million after only two years of his ownership.18

Compounding Smulyan’s financial dilemma was the lease for use of the Kingdome. He quickly came to Argyros’ conclusion that the Kingdome was a substandard venue for fielding a competitive baseball team.

The Kingdome was a domed, multipurpose stadium built just south of the downtown area of Seattle (Sodo) in anticipation of obtaining an NFL and/or a major-league baseball franchise. Construction began in 1972 through voter-approved bond funding of $40 million. It opened in 1976.

Over the years, very few improvements had been made. When Smulyan purchased the team in the late 1980s, he began additions such as an upgraded sound system and a new scoreboard. However, in general the overall lack of improvements led the Smulyan and the other tenants of the stadium to begin to lobby for construction of a new ballpark and to threaten relocation if this wasn’t approved.

Despite significant attendance increases, and the Mariners’ first winning season, in 1991, revenues remained well below those of other American League teams. After steady losses under his ownership, Smulyan announced that the Mariners were for sale. It was rumored that he wanted to move the team to Tampa.19

In his announcement, on December 4, 1991, Smulyan said that the team was for sale for $100 million. He had been ordered by Security Pacific Bank to repay a loan of nearly $40 million or find a buyer for the team.20 Smulyan said the team would be offered to local buyers first, which was required by its lease with the Kingdome. Officials in St. Petersburg, Florida, who had failed to gain a National League expansion franchise, said they were set to lure the Mariners to Florida to play in the Florida Suncoast Dome.

Independently, Slade Gorton, now in the U.S. Senate, contacted prospective purchasers, including Hiroshi Yamauchi, owner of Nintendo Co., in an effort to keep the team in Seattle.21

Under the terms of the Kingdome lease, local investors had 120 days to come up with a purchaser to keep the team in Seattle. Senator Gorton, in his capacity as a member of the Senate Commerce Committee, had worked to assist Nintendo, a Japanese-owned company with U.S. headquarters in Redmond, Washington, to curtail counterfeiting of their video games. Early in December 1991, he called Howard Lincoln, senior vice president of Nintendo’s American division, to ask for a meeting to talk about an investment.

On December 23, 1991, Gorton received a call from Lincoln and Minoru Arakawa, head of Nintendo’s American division and Yamauchi’s son-in-law. Nintendo was very grateful to the United States and to the State of Washington for its successes there. If Seattle needed $100 million to keep baseball in town, Yamauchi would contribute it out of his own pocket.22

Gorton was thrilled with the offer, but he realized that local ownership was instrumental to keeping baseball in Seattle for the long haul. He set to work putting together a group of local investors to join Nintendo as minority partners. A key goal was to overcome opposition to foreign ownership, especially a Japanese owner. He and Howard Lincoln brought in John Ellis, then head of Puget Sound Power and Light (later Puget Sound Energy), to craft the plan.

On the brink of leaving the Northwest, the Mariners received an offer from Yamauchi to contribute $75 million toward the purchase of the team as a gift to Seattle. Controversy ensued when some baseball traditionalists raised their voices against what they saw as selling out America’s pastime to the Japanese. Major League Baseball ultimately agreed to a 60 percent acquisition by Yamauchi on condition that he limit his voting interest to 49 percent. Local investors contributed the remainder of the $125 million total sale price.

The Kingdome was home to the Seattle Mariners from 1977 to 1999. (Courtesy of David S. Eskenazi)

Nintendo

On July 1, 1992, under the restrictions set forth by Major League Baseball, The Baseball Club of Seattle, LP, assumed control of the Mariners. Chuck Armstrong returned as president and chief operating officer, while the board of directors included John Ellis (chairman), Minoru Arakawa (representing Hiroshi Yamauchi, whose reluctance to fly kept him from ever attending a single Mariners game), Chris Larson, Howard Lincoln, John McCaw, Frank Shrontz, and Craig Watjen. Rumblings also began about the need for the Mariners to have a new ballpark to truly attain long-term success in Seattle.23

The new group’s first full season of control saw them begin to put the pieces in place for future Mariners success, on the field and at the box office. It began with the hiring of Lou Piniella, who would go on to become the most successful and longest tenured manager in Mariners’ history.

This new ownership group would burn through $77 million in losses during their first seven seasons and received criticism from the media and some sectors of the public over the fight to get a new ballpark approved and built. But the singular goal of this management team was to keep the Mariners in Seattle, which they ultimately achieved. Additionally, over time, the stability of this ownership group would allow the Mariners to grow into a vital local team, as judged by positive community support, buttressed with a few outstanding seasons.

In 1993 Peoria, Arizona, finalized an agreement between the city, the Mariners and the San Diego Padres to build the Peoria Sports Complex.24 This was the first spring-training site to host two major-league teams. It contained 12 practice fields, two team clubhouses, and office facilities for both teams. The site has since become a destination for Seattle fans looking to escape the wet winters of the Pacific Northwest. A 2014 upgrade, which coincided with a lease extension until 2034, renovated clubhouses, added dining space and improved the fan experience.

The 1994 season proved to be a debacle. The season was shortened by the players strike, although by game 65, Ken Griffey Jr. had already hit 30 home runs. At the time of the strike, the Mariners, despite a record of 49-63, were only two games out of first place in the American League West Division. Then the roof fell in, literally. On July 19, 1994, an hour before the Mariners were to host the Baltimore Orioles; a four-foot-long acoustical ceiling tile fell 180 feet from the roof of the 18-year-old Kingdome. Additional tiles fell and before long it was realized that all 40,000 fiberboard tiles needed to be replaced before the ballpark could be used again.25

The Mariners were forced to play the last 20 games of the 1994 season on the road after the players union vetoed playing the “home” games at Cheney Stadium in Tacoma, BC Place Stadium in Vancouver, British Columbia, or some neutral site, as the union believed its members should play only in major-league venues. The extended road trip could have lasted over two months, but was shortened by the players strike, which began on August 12.26 It was the team’s longest road trip ever — 20 games in 21 days spanning 10,425 miles. “It was the longest road trip, the biggest laundry bill, and the most suitcases,” Edgar Martinez said with a smile. The incident further inflamed the debate about the Kingdome’s suitability as a baseball facility and the Mariners’ quest for a new ballpark.27

The next year, 1995, turned out to be a critical one for the Mariners, with ups and downs on the field, the return from the players’ strike, playoff drama as exciting as ever seen in sports, and the off-the-field angst of Kingdome replacement votes and local politics.

It began with the suspension of the strike on April 2, 1995. Under the terms of an injunction issued by Federal Judge Sonia Sotomayor, the players and owners were to be bound to the terms of the expired collective-bargaining agreement until a new one could be reached. The start of the season was postponed for three weeks for an abbreviated spring-training period, after which the teams would play a 144-game season instead of the normal 162.28

On March 30, 1994, King County executive Gary Locke had appointed a task force to assess the need for a new ballpark to replace the rapidly deteriorating Kingdome. Many feared that the Mariners would leave Seattle if a new one wasn’t built. In January 1995, the 28-member task force recommended to the King County Council that the public should be involved in the financing of the ballpark. The task force concluded that a sales-tax increase of 0.01 percent would be sufficient to fund the ballpark. King County held a special election in September 1995, asking the public to approve the sales-tax increase.29

The voting came amid a run to the Mariners’ first playoff appearance. The run began on August 24. That day, in the first of a four-game series against the New York Yankees, Griffey blasted a two-run walk-off home run to win the game. From that day, the Mariners went 25-11 to the end of the regular season, seemingly discovering a new hero each night. “Refuse to Lose” became the mantra of the team and its fans, as the Mariners battled from their deficit to catch the Angels and force a one-game playoff.30

On September 19, while the Mariners pulled off another “Refuse to Lose” win, the King County referendum to fund a new ballpark failed by a tenth of a percentage point. It was remarkable that the vote count was so close, as polls only a month earlier had shown support from only a third of voters. The 1,082-vote margin of defeat (out of nearly half a million cast), however, had signaled a dramatic change of public opinion. County officials would meet over the next several months to draft funding plans for a new ballpark despite the ballot failure.

The team entered some of its greatest years. Under the leadership of Lou Piniella, they built their team around Ken Griffey Jr., Randy Johnson, and Edgar Martinez. After the magical 1995 season and building on the momentum of the dramatic playoff series against the Yankees, the Mariners and their supporters in the community were able to pressure the Seattle City Council into a special session in which they devised a new stadium plan that sidestepped the results of the previous year’s failed ballot initiative and approved construction of a retractable-roof ballpark in downtown Seattle.

On October 14, 1995, a special session of the state legislature authorized a different funding package for a new ballpark that included a food and beverage tax in King County restaurants and bars, a car-rental surcharge in King County, a ballpark admissions tax, a credit against the state sales tax, and sale of a special stadium license plate. Nine days later, the King County Council approved the funding package and established the Washington State Major League Baseball Stadium Public Facilities District to own the ballpark and oversee design and construction. Taxpayer suits opposing the legislative actions and the taxes failed in the courts. The new ballpark would open less than 3½ years later.31

The excitement of the 1995 season carried over at the box office, as the team’s attendance exceeded 2.7 million in 1996.

On September 9, 1996, the site was selected for the new ballpark, just south of the Kingdome. In late fall, several members of the King County Council asked the Mariners to consider postponing construction and the opening of the projected $384.5 million stadium. In response, the Mariners said they would either sell the team or move it from Seattle.32

“Reluctantly, after more than five years of work, (we) have concluded that there is insufficient political leadership in King County to complete the new stadium by 1999,” the owners said in a five-page statement that Mariners CEO John Ellis read at a downtown news conference. “This is not a bluff.”33 After a public outcry, the King County Council voted to reaffirm its cooperation with the Mariners in building a new ballpark, and the Mariners contributed $145 million to cover cost overruns, ending this short-lived threat.34

Construction officially began on March 8, 1997, with a ground-breaking ceremony featuring Ken Griffey Jr. The construction, overseen by Mariners chief financial officer Kevin Mather, who later became president of the Mariners, continued until July 1999, when the new ballpark officially opened.

Ken Griffey Jr. was the face of the Seattle Mariners, and arguably all of baseball, in the 1990s. The Kid’s popularity helped usher in a new era for the franchise, including the building of a new, open-air ballpark called Safeco Field. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

In 1999 the Mariners hosted two home openers and one stadium finale. The first home opener was the traditional Opening Day, April 5, in the Kingdome against the Chicago White Sox. On June 27 the team played its final game in the Kingdome when more than 56,000 fans watched the Mariners defeat the Chicago White Sox.35 Griffey hit the final home run during that game. Nearly three weeks later, on July 15, the second home opener was played, christening Safeco Field.

Seattle’s new ballpark was built to resemble the great ballparks of the past. It was open-air and had real grass, but also featured a retractable roof that covered the ballpark without enclosing it. The roof kept fans, 47 percent of whom come from outside the immediate Puget Sound area, protected from the wind and rain.36

The 2000 season saw lots of new faces who would make positive impacts for the Mariners over the next few seasons. The key to the offseason was the trade of Griffey to the Cincinnati Reds.

During 1999 Griffey had become disenchanted with the Mariners and demanded a trade. He told the club that Seattle had become inconvenient for his family, which lived most of the year in Florida.37 He declined a $148 million extension. As a 10-and-5 player (10 years in the majors, 5 consecutive years with the team), he had a right to veto any trade, and exercised that right in potential deals with the New York Mets and Atlanta Braves before agreeing to a trade to his hometown Cincinnati Reds.38

The Mariners’ 25th season since their inception, 2001, was a remarkable year in which they tied the major-league record for wins by an American League team, with a record of 116-46. They led the majors in runs scored and fewest runs allowed. Fans adopted a slogan “2 outs, so what,” because the Mariners were so successful scoring runs after there were two outs. They scored a franchise-record 339 after there were two outs.39

The season actually began in the offseason. While they lost Alex Rodriguez to free agency, the Mariners signed Ichiro Suzuki, who had played for the Orix Blue Wave of the Japan Pacific League.40 They followed by signing second baseman Bret Boone, an original Mariner draft pick in 1990.41

The team had a strong lineup and deep bench. It led the league in hitting, pitching, and defense. Four starting pitchers won 15 games or more and Kazahiro Sasaki saved 45 games. The 2001 All-Star Game, played at Safeco Field, saw eight Mariners selected to play, including four starters. Ichiro Suzuki won the batting title and was voted both the American League MVP and Rookie of the Year. Bret Boone, who hit 37 home runs and drove in 141 runs, was third in the MVP voting and set a record for most runs driven in by a second baseman. Lou Piniella was the American League Manager of the Year.

But the team lost to the New York Yankees in the American League Championship Series.

During this period, the team had the benefit of an enchanting new ballpark and a period of winning teams, so the Mariners were among the league leaders in attendance. In three consecutive years attendance exceeded 3 million, with a high of 3.27 million in 2003.

In 2004 Yamauchi ceded control of his shares to Nintendo of America for estate-planning purposes so the team could continue functioning normally in the event of his death.

Attendance remained strong in 2004, approaching nearly 3 million fans. However, performance on the field fell badly; the team lost 30 more games than in the previous season, finishing last in the American League West at 63-99.

From 2004 through 2006, the Mariners experienced losing seasons, and attendance correspondingly dropped. The decrease averaged over 250,000 fans each year. The 2007 season saw a reversal on the field (88-74, second in the NL West) and a reversal at the gate (2.67 million, up 200,000). Despite the team’s improvement, there were concerns about the size of the payroll, which exceeded $105 million. It was essential that, at a minimum, the team challenge to make the playoffs. Both the ownership and the fans were concerned about the team’s performance and expected more.

Overcoming the concerns about payroll, there was hope and anticipation about the 2008 season after the Mariners’ success in 2007. The owners demonstrated their endorsement by taking on extra salary, highlighted by the addition of pitchers Erik Bedard and Carlos Silva. Obtaining these players resulted in the loss of key minor-league talent.42 However, the team fell flat during the 2008 season, as Bedard pitched in only 15 games and Silva ended up with a 4-15 record and an ERA of 6.46.

That season, the team started slowly and never recovered, finishing with a 61-101 record, last in the American League West. The season was marred by key leadership changes, starting with the firing of general manager Bill Bavasi on June 16 and the appointment of Lee Pelekoudas, the team’s vice president/associate general manager, as the interim GM. “Change is in order,” Mariners CEO Howard Lincoln said. “We have determined new leadership is needed in the GM position. With a new leader will come a new plan and a new approach. A search will begin immediately for a permanent GM, and Lee will be a candidate for the position.”43

On October 22 Milwaukee Brewers executive Jack Zduriencik, who was most notable for his drafting skills and was credited with turning the Brewers into a playoff team, was named the Mariners general manager.44

Fan enthusiasm had been on the wane for several years. Attendance fell below 2 million in 2011 for the first time since 1995 and dropped to as low as 1.7 million in 2013.

On September 19, 2013, Hiroshi Yamauchi died. He was 85 years old and had never attended a live Mariners game, including declining to travel from his home in Kyoto to Tokyo in March 2012 when the Mariners played a series of exhibition games there and later opened their season against the Oakland Athletics.

However, Yamauchi had retained titular control. His death meant Lincoln, the former Nintendo lawyer and cherished Yamauchi friend and confidant, retained almost full control and decision-making power in the organization.45

In recent years, powered by the earning capability of Safeco Field, the value of the Mariners had surged. The team in early 2013 partnered with DirecTV to form Root Sports NW, a regional sports network that covered six states and was believed to add at least $200 million to the team’s value. The Mariners’ official valuation would rank eighth in baseball on the annual Forbes list, nestled between the $1.6 billion St. Louis Cardinals and the $1.34 billion Los Angeles Angels.46

John Stanton

This led Nintendo, which had retained majority ownership of the club, to consider selling the franchise. On April 27, 2016, a 17-member local group led by John Stanton bought a majority interest in the baseball team in a deal that valued the team at $1.4 billion. While Nintendo sold its majority interest, it kept a 10 percent minority interest in the club.47

Stanton, who replaced Howard Lincoln as chairman and CEO, was raised in the Seattle area. He was a wireless industry pioneer who worked with John McCaw to form the first nationwide cellular network in the 1980s. He also led Western Wireless and VoiceStream Wireless, the predecessor to T Mobile.

Marketing, Promotions and Fan Experience

Part of the character of the team has been ownership’s ability to create a positive fan experience. The goal was to create a friendly and lively atmosphere at the ballpark. The team also looked to translate this atmosphere to its broadcasts, both on television and on the radio. This goal was confirmed as the team garnered excellent ratings for televised games.48

The marketing focus began under the ownership of Jeff Smulyan. After he sold the club in 1991, the marketing and community focus was continually enhanced, especially as the team become ensconced in its new ballpark, enjoyed some on-field success and removed the threat of relocation.

The marketing plan included highly regarded TV commercials and unique promotions. Beginning early in their existence, the Mariners used team personnel to build its personality and improve fan recognition. Commercials were initially shown each year during spring training. Examples of these ads can seen here.

The marketing plan included highly regarded TV commercials and unique promotions. Beginning early in their existence, the Mariners used team personnel to build its personality and improve fan recognition. Commercials were initially shown each year during spring training. Examples of these ads can seen here.

On April 13, 1990, the Mariners unveiled its first mascot, the Mariner Moose. The Moose was selected after a contest in which more than 2,500 entries were submitted by children 14 and under from throughout the Pacific Northwest. The winning idea came from Ammon Spiller, a fifth-grader from Central Elementary School in Ferndale, Washington, who wrote: “I chose the Moose because they are funny, neat and friendly. The Moose would show that the Mariners enjoy playing and that they still have a few tricks up their sleeves. It shows they’re having fun no matter what the situation.”49

Over the years, besides traditional ballpark fare, the team has offered several creative food items or eating establishments at the ballpark:

- The Ichiroll, a sushi roll made of spicy tuna with black sesame seeds, wasabi, and daikon radish sprouts and named after Ichiro Suzuki.

- Edgar’s Cantina, a two-level restaurant and bar located on the Home Run Porch, named after Edgar Martinez.

- In 2017, the team introduced Oaxacan chapulines, or toasted grasshoppers covered in chili-lime salt, which sell for $4 for a 4-ounce cup.

- Ivar’s, a prominent Northwest seafood restaurant that offers menu items such as clam chowder, salmon sandwich and the Ivar dog.

The team has always offered traditional promotions to bring fans into the ballpark, such as bat day, little league days and bobbleheads. The team has also created many unique promotions such as the following:

- Funny nose and glasses — Former Mariners outfielder Tom Paciorek was well known for his sense of humor. When the Mariners were creating their commercials for 1981, they produced a spot promoting Jacket Night that had Paciorek asking, “What am I going to do with 30,000 pairs of funny nose glasses?” The Mariners say the spot generated many calls and letters from fans wanting to know when Funny Nose Glasses Night would be. In fact, some fans came to the Jacket Night game and were disappointed, as they wanted a pair of funny nose glasses. They finally got them in 2012 when the Mariners held a special day to celebrate their 35th anniversary.50

- Buhner Buzz — Of all the Mariners promotions, perhaps the most popular was Buhner Buzz Cut night. In a celebration of outfielder Jay Buhner’s signature bald pate, all bald fans got in free, and others could get their head shaved outside the ballpark for free admission to the game. It was first held at the Kingdome in 1994 and every year through 1999, then again in 2001. Buhner even buzzed some fans himself. Over the years, more than 22,000 people took advantage of the buzz.51

- King’s Court — In 2011 the Mariners launched the King’s Court. Whenever Felix Hernandez pitched, fans could buy tickets for a special section, a yellow T-shirt and a yellow “K” card. During the game, a chef brings a turkey wing to the most spirited fan in the section.

- Beard hat — With so many players (and Seattle hipsters) sporting facial hair, someone thought it would be fun to give away a knit hat with faux facial hair. Needless to say, Beard Hat Night was a hit.

- Turn ahead the clock — Inspired by the Back to the Future movies, in 1998 marketing director Kevin Martinez (now a club vice president) came up with Turn Ahead the Clock night. It featured the Mariners and Royals in futuristic uniforms designed with the help of Ken Griffey Jr. As ESPN recounted, the game featured the Kingdome getting renamed the Biodome for the night, a ceremonial first pitch delivered by a robot from the University of Washington, and a first pitch thrown out by James Doohan, who played Scotty on the original Star Trek, making his way to the mound in a DeLorean, the auto that was featured in the movies.

- Larry Bernandez — This character was a Felix Hernandez alter-ego born from a commercial released in 2011 in which Hernandez disguised himself to try to pitch more often. From this commercial, the Mariners continued to promote Bernandez, including a Larry Bernandez bobblehead giveaway, a Facebook page, and a twitter feed.

- Barry White night, August 6, 2000 — White threw out the ceremonial first pitch and was the public-address announcer for part of the game.

During the seventh-inning Stretch, following the traditional chorus of Take Me Out to the Ball Game, the Kingsmen’s version of the cult song “Louie Louie” is played.

Robert Ruvkun was an employee of the Kingdome in the early 1990s when he began dancing during a game against the Minnesota Twins. He was encouraged to take the act out into the stands and became known as “Bad Dancer.” After he was no longer a Mariner employee, he continued to attend five to ten games each season and was highlighted on the scoreboard when his song was played between innings. He performed in Cooperstown at a Mariners party when Ken Griffey Jr. was inducted into the Hall of Fame.52

In 2007 television color commentator Mike Blowers noticed that a spectator had dropped his fries in an attempt to catch a foul ball. He and play-by-play announcer Dave Sims sent an intern down with free garlic fries. After this occurred, the Mariners rallied and won the game. The next game, a different spectator brought a sign to Safeco Field asking Blowers for free fries. Blowers obliged, and the M’s went on to score five runs that inning, winning 9-4. They also won the rest of the games on that homestand. Fans began asking Mike Blowers for Rally Fries and a tradition was born. (Rally Fries were retired in 2012.)53

For several years through 2015, several members of the Safeco Field grounds crew dance to a popular song. The choreographed routine changed over time.

Last revised: October 23, 2018

Safeco Field has been home of the Seattle Mariners since 1999. (Photo by David Schott via Flickr.com. Creative Commons, CC BY 2.0)

Notes

1 David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman, “Wayback Machine: Dwyer KO’s American League,” SportsPressNW, October 25, 2011, http://sportspressnw.com/2124781/2011/wayback-machine-bill-dwyer-kos-american-league.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Baseball Club of Seattle LP, International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 50 (Farmington Hills, Michigan: St. James Press, 2003).

5 Lester M. Smith obituary, Seattle Times, October 27, 2012.

6 Larry Stone, “Former Mariners GM Lou Gorman,” Seattle Times, April 1, 2011.

7 David B. Bissell. Can You Name That Team? (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2003), 64.

8 MLB Expansion Drafts History, https://baseball-reference.com/draft/1976-expansion-draft.shtml.

9 Seattle Mariners Baseball Information Department, From the Corner of Edgar & Dave, marinersblog.mlblogs.com/on-this-date-mariners-play-inaugural-game-4984af8e53e3.

10 Carol Beers, “Stanley Golub, 85; Jeweler Was Part Owner of Mariners,” Seattle Times, October 19, 1998.

11 SPNW Staff, Mariners: Ownership, Organizational Timeline, sportspressnw.com/2163322/2013/mariners-ownership-organizational-timeline.

12 David Schoenfield, “The Top 10 Worst Owners in MLB History,” ESPN.com, June 27, 2011.

13 UPI Archives, “George Argyros, Principal Owner of the Seattle Mariners, Denied…,” December 1, 1981.

14 UPI Archives, “Seattle Mariners Owner George Argyros Friday Denied a Report…,” February 1, 1985.

15 SPNW Staff, Mariners: Ownership, Organizational Timeline.

16 “Mariners’ Owner Rejects $37-Million Bid,” Los Angeles Times May 13, 1987.

17 Richard Sandomir. “Mariners’ Ex-Owners Make Off with Booty,” New York Times, June 12, 1992.

18 Glen Drosendahl. “A Group of Local Investors Announces Plans to Buy the Seattle Mariners on January 23, 1992,” HistoryLink.org, Essay 9562.

19 Mike McKay. “The Unlikely Champion Who Saved the Seattle Mariners,” Seattle Times, May 11, 2016.

20 Larry LaRue. “Owner Scapegoat in Mariners’ Financial Woes,” McClatchy News Service, August 25, 1991.

21 Ibid.

22 McKay.

23 FundingUniverse.com, “The Baseball Club of Seattle, LP History,” https://fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/the-baseball-club-of-seattle-lp-history/.

24 ThebaseballPHD, https://thebaseballphd.wordpress.com/2013/03/26/peoria-sports-complex-20th-anniversary/.

25 Jordan Miller, “King Dome — Roof Performance Failures and Ceiling Collapse,” Pennsylvania State University, July 19, 1994.

26 Bob Condotta, “Ten years after the Kingdome tiles fell,” Seattle Times, July 19, 2004.

27 Ibid.

28 Mark Maske, “Baseball Strike Ends,” Washington Post, April 3, 1995.

29 David Wilma, “Voters Reject a Stadium for the Seattle Mariners on September 19, 1995,” historylink.org essay 3429, July 5, 2001.

30 Jerry Brewer, “‘Refuse to Lose’ Season Spawned Generation of Young Mariners Fans,” Seattle Times, December 28, 2009.

31 Steve Campion, “Refuse to Lose: The Last 36 Games of the 1995 Mariners Season,” WA-list, September 13, 2015.

32 Glenn Drosendahl, “Safeco Field, the Seattle Mariners’ Long-Sought Stadium, Opens on July 15, 1999,” HistoryLink.org, September 11, 2010.

33 Elliott Almond, David Schaefer, Richard Seven, Stephen Clutter, “Mariners Put Up for Sale — Owners Blame Council Members for Discussing Ballpark Delay,” Seattle Times, December 15, 1996.

34 Ibid.

35 https://baseball-reference.com/boxes/SEA/SEA199906270.shtml.

36 https://ballparks.com/baseball/american/seabpk.htm.

37 Dean Paton, “Fans Weep at the Idea of Seattle Sans Junior; Ken Griffey Jr.’s Desire to Leave the Mariners Has Left Many Fans,” Christian Science Monitor, January 7, 2000.

38 Dave Sheinin, “Mariners Trade Griffey to Reds,” Washington Post, February 11, 2000.

39 Steve Rudman, “Mariners Revive Slogan: ‘Two Outs, So What!’” SportsPressNW, April 9, 2017.

40 Associated Press. “In a First, Mariners Sign Japan’s Suzuki, an Outfielder,” New York Times, November 19, 2000.

41 https://baseball-reference.com/teams/SEA/2001-transactions.shtml.

42 Associated Press, “Orioles Trade Bedard to Mariners for Five Prospects,” ESPN.com, February 9, 2008.

43 Geoff Baker, “Mariners Fire GM Bill Bavasi,” Seattle Times, June 16, 2008.

44 Larry Stone, “M’s Hire Brewers’ Jack Zduriencik as GM,” Seattle Times, October 22, 2008.

45 Geoff Baker, “Mariners Sale: How John Stanton’s Seattle Group Struck a Deal with Nintendo of America,” Seattle Times, April 27, 2016.

46 Ibid.

47 Ibid.

48 Geoff Baker. “Better Baseball Means Better TV Ratings for Mariners,” Seattle Times, September 22, 2014.

49 Mariners.com, https://mlb.com/mariners/fans/mariner-moose.

50 MarinerPR, “Tom Paciorek and ‘Funny Nose Glasses Night,’” Marinersblog.com, August 31, 2012.

51 Michael Clair, “One of the Greatest Baseball Promotions: Watch Jay Buhner Shave Heads for ‘Buzz Cut Night,’” mlb.com, May 19, 2015.

52 Kipp Robertson. “Seattle Mariners Fan Keeps His Bad Dance Alive,” mynorthwest.com, March 24, 2015.

53 https://baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Rally_Fries.