Toronto Blue Jays team ownership history

This article was written by Allen Tait

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

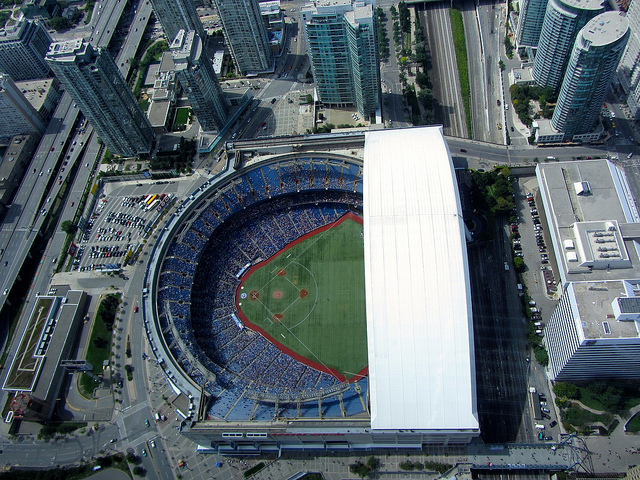

The Toronto Blue Jays have played at the Rogers Centre, previously known as SkyDome, since 1989. (Creative Commons 2.0 image by Oliver Mallich)

Quest for a Franchise

Canadian sports conjure up images of ice hockey, curling and three-down football. However, baseball has a long and somewhat overlooked place in the Canadian sports scene. Prior to the arrival of major-league baseball in Canada (Montreal 1969, Toronto 1977), Toronto has had teams in baseball leagues since 1876,1 notably the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League from 1912 to 1967.

Paul Godfrey, first elected a Toronto alderman in 1968, played a key role in attracting major-league baseball to Toronto. Several factors spurred Godfrey’s initiative:2 The International League team moved to Louisville, Montreal acquired the Expos and Toronto’s entry was reduced to an intercounty league franchise3 for the 1969 season.

In 1969 Godfrey approached Commissioner Bowie Kuhn in the Fort Lauderdale hotel where the winter baseball meetings were being held and asked for a franchise. The response: “Let me tell you the way we do it in major league baseball. First, you build a stadium. And then we consider if we want to give you a baseball team.”4

Little progress was made until 1973. Godfrey had been re-elected and was selected as chair by his fellows. Godfrey promised to deliver a baseball franchise, domed stadium and conference center.5 Obtaining financing to build a ballpark did not seem feasible so the focus was on renovating the existing Exhibition Stadium, which was then used for the Canadian Football League’s Toronto Argonauts and rock concerts. In November 1973 Godfrey approached Ontario Premier William Davis with the following plan:6

- Use the existing covered north grandstand as bleachers.

- Build a new south grandstand near where home plate would be located.

- Extend a temporary fence between the grandstands to establish the outfield.

- Municipal council will contribute $7.5 million (all monetary figures in this essay are in Canadian dollars unless otherwise noted).

- Godfrey asked Davis for a similar amount. (Davis responded that no grant would be available, but an interest-free loan would be approved.)

Public support for the agreement was divided, likely because of economic conditions at the time. For example, according to Statistics Canada, the inflation rates for Canada from the years 1973-1975 were 7.8 percent, 11.0 percent, and 10.7 percent respectively. Notwithstanding public concerns, the Metro Toronto council did approve the renovation project, at an estimated cost of $15 million, by a vote of 23 to 6 in 1974. Further, the investment was considered a temporary facility until a domed stadium could be built. The actual renovation cost was $17.8 million.7

Now that government financial support for a temporary stadium was established, local businesspeople began assembling ownership groups to approach Major League Baseball and request a franchise. Initially three groups demonstrated interest.8 One was fronted by Sydney Cooper, owner of C.A. Pitts Engineering Construction Ltd., which specialized in large-scale energy development, multi-lane highways, bridges, dams, tunnels, and marine construction.9 Shortly after Montreal had obtained the Expos, Cooper formed the Toronto Baseball Company, comprising himself, his three Toronto business partners, and two Americans with connections to major-league baseball.10 The Cooper group, initially interested in a National League franchise, also courted franchises not drawing well and supported Godfrey’s efforts to obtain stadium renovation funding. Ultimately, the Cooper group did not obtain the franchise as “after softening the ground, Cooper stepped aside as Labatt Breweries and others took up the cause.”11 A contributing factor appeared to be Cooper’s being one of five men charged with defrauding the public of $4.2 million by bid-rigging on seven dredging contracts between 1969 and 1975. He went on trial in February 1978, was convicted May 1979, and began serving his sentence when his appeal was denied in 1981.12

A second unsuccessful group was headed by Lorne Duguid, a vice president of Hiram Walker and Sons distillers. The group included Harold Ballard, then owner of the Toronto Maple Leafs of the National Hockey League.13 It is interesting to note, as recounted in the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation digital archives, that Ballard also had legal issues. He had been convicted on 48 counts of fraud, theft, and tax evasion in August 1972 for diverting business assets of $205,000 from his sport franchise for personal use. He was sentenced to nine years in prison but was released on parole in October 1973.

The successful group was fronted by the Labatt brewery. At the time the Canadian beer market was dominated by three breweries, Labatt, Molson, and Carling O’Keefe. While each brewery had a dominant market segment, Labatt did not have a strong presence in urban Ontario14 and Toronto was (and remains) the largest urban center in the province. Completion of a feasibility study in 1974 confirmed that Labatt would benefit from associating with baseball.15

Initially the Labatt group approached the Cooper group about arranging marketing rights for Labatt should Cooper obtain a franchise. Cooper, after consulting with his partners, advised, “They thought that being associated with a brewery would be a bad idea, because it would adversely affect their chances of getting a franchise.”16 The Labatt group thought this response was “kind of strange,”17 and Commissioner Bowie Kuhn confirmed that there was no issue with brewery involvement given that three clubs (Orioles, Cardinals, and Brewers) were owned by breweries.18 The Labatt board then authorized pursuit of a franchise provided the Labatt stake did not exceed 50 percent.19 To find partners, a high-level Labatt executive suggested contacting the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC). The bank was interested but under Canadian law could not own more than 10 percent of a business. The bank chairman suggested a friend of his, businessman Howard Webster, who had previously expressed an interest in baseball. Labatt (45 percent) ultimately partnered with Webster (45 percent) and the CIBC (10 percent).20

During the period of the Exhibition Stadium renovations, there had been some preliminary discussions about the possibility of the Cleveland Indians, San Diego Padres, or Baltimore Orioles moving to Toronto although none of these discussions progressed to an announcement of a franchise move.21 This was not the case in 1975 with the San Francisco Giants.

The Giants and owner Horace Stoneham were in financial trouble and for sale. Labatt calculated the value of the Giants at $8 Million US. However, there were competing bids of $10 million from a Washington, D.C., group and $15 million from the still-active Ballard group. Labatt came in with a bid of $12.5 million US.22 On January 9, 1976, at 4:52 P.M. EST, Godfrey announced that the Giants’ board had approved the sale and transfer of the team to the Labatt group, pending National League owners’ approval. The price was $12 million US plus $1 million in trust for potential legal costs associated with breaking the Candlestick Park lease.23 San Francisco Mayor George Moscone immediately took legal action that led to the issuance of a temporary restraining order against the transfer. By March 2, 1976, Moscone had found a local ownership group and the National League owners approved them, keeping the Giants in San Francisco.

The existence of a natural rivalry with the Expos, combined with the near transfer of the Giants, meant that the Toronto ownership groups were focused on the National League. Little attention had been paid to pending expansion in the American League. The Seattle Pilots had relocated to Milwaukee after their inaugural 1969 season. The State of Washington had filed a $32 million antitrust lawsuit against the American League and the suit was dropped when the American League agreed to expand for the 1977 season.24 A second franchise was expected to be awarded at an American League owners meeting scheduled for March 29, 1976, to avoid complexities of a 13-team league. The owners were willing to hear presentations from any group interested in a franchise.

Having “lost” the Giants officially on March 2, the Labatt group had 27 days to prepare a bid for an expansion franchise. Beyond other cities interested in a franchise, Labatt also faced competition from a recently assembled Toronto-based corporate consortium fronted by five business entities and leaders including Carling Brewery and businessman Trevor Eyton. Jerry Hoffberger, owner of the Orioles, having had brewery business dealings with Carling, was supportive of the Carling bid.

On March 29 the American League owners met and listened to presentations from all interested bidders, including the two bids from Toronto. The Labatt bid was accepted by a vote of 11 to 1. Hoffberger, supporting the Eyton group, was the lone dissenting vote. Hence, Labatt was awarded a franchise for $7 million US.25 Eyton later became an important factor in construction of the domed ballpark.

American League President Lee MacPhail stated, “Several cities contacted us. Toronto was our first choice. Toronto is a large metropolitan area. The city has a newly remodeled stadium satisfactory to us. It’s just being completed now. For baseball, it will hold about 50,000.”26 MacPhail did not identify the unsuccessful cities that bid, but it was public knowledge that Commissioner Kuhn was interested in placing a franchise in Washington. Given that American League teams had left Washington in 1961 and 1972, it is not unreasonable to surmise that this was a factor in the American league choosing a new market in Toronto over placing another expansion franchise in Washington.

The eight-year quest for a franchise (1969-1976) had required a political and business partnership, but there was some elbowing over dividing the credit. “Godfrey was very helpful from a general point of view as far as getting the stadium and baseball going and getting people to appreciate the desirability of Toronto,” said an anonymous observer with connections “back to the franchise’s beginnings.” “But he didn’t play any role in getting the team. The guys at Labatt resent Godfrey being credited with bringing baseball to Toronto, because he didn’t put up the money. I think Godfrey deserves a reasonable amount of credit for bringing baseball to Toronto, but I think calling him ‘the man who brought baseball to Toronto’ is a bit of an overstatement. Still, Godfrey hasn’t postured to get more credit than he deserves. And I think the Labatt resentment was an over-reaction.”27

The new ownership group, fronted by Labatt, faced an early controversy over the selection of Blue Jays as the team name. A name-the-team contest reportedly generated 4,000 names from 30,000 entries. Given that a prominent beer brand for Labatt at the time was Labatt’s Blue, there was some negative media and public suspicion that selection of Blue Jays was a marketing ploy. A Labatt spokesmen replied, “It wasn’t lost on us but it wasn’t decided because of that. It was probably a 10 percent factor.”28

The ownership group also faced financial pressure because the Ontario government prohibited the sale of beer at Exhibition Stadium.29 A group calling itself the “No Booze at the Ballpark Committee” convinced the Ontario government that the sale of beer would create a rowdy environment, dangerous drivers would leave the ballpark, and it could lead to a slippery slope where beer would be sold at hockey games and other sporting events. Fans unhappy with the decision referred to the ballpark as Prohibition Stadium. The decision stayed in place until July 30, 1982, when the Ontario government allowed beer to be sold on a trial basis.

Local broadcasting rights were another area of negotiation. In 1977 there were no Canadian specialty sport channels. There were two primary national television networks. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) was a Canadian Federal Corporation and served as the nation’s public broadcaster. The other network was the privately owned CTV. For 1977, CBC paid $1.2 million to broadcast 46 Blue Jays games in English and 18 in French.30 By 1980, local television rights had grown to $3 million.31

Opening Day in Toronto, April 7, 1977, as a snowstorm blankets the field at Exhibition Stadium. (Courtesy of Elliott and Helene Wahle)

The Building Years: 1977-1982

Labatt, as the public face of the ownership group, brought a business perspective to operating the ballclub. Lacking executives with major-league baseball experience, Labatt hired key personnel with such experience. Notable among the early hires were Peter Bavasi, son of Buzzie Bavasi, as general manager, and future Hall of Famer Pat Gillick as assistant general manager. In December 1977 Bavasi was promoted to club president, remaining in the post until 1981, and Gillick was promoted to general manager, serving until 1994.

The owners treated the baseball club as an operating division and required an annual operational plan. This allowed Bavasi and Gillick to demonstrate they had business sense while setting realistic ownership expectations. For example, expansion teams usually have limited success in the early years, with attendance falling as the novelty wears off. The first plan was presented in the fall of 1977 after completion of the first season.32

- The financial success of 1977 was not entirely expected and should not be expected in 1978 as novelty will be absent.

- Long-term financial success is expected based on the area’s population density, high disposable income, success of other area professional teams, perception of inexpensive family entertainment, credible ownership and good public relations.

- To maintain fan interest going forward, signs of improvement must be shown necessitating a total financial and philosophical commitment to player acquisition and development by ownership and management.

A note about exchange rates: Most of the Blue Jays revenue was received in Canadian dollars and most expenses (player salaries, travel) are paid in US dollars. Although the Canadian dollar has briefly traded a few cents above the US dollar while the Blue Jays have been in operation, Bank of Canada charts show that the Canadian dollar has trended around 80 cents to the US dollar (occasionally dipping a few cents below 70). As a result, the Blue Jays incur an expense premium that has reached as high as 35 percent. Financial tools such as forward exchange contracts are often used by Canadian companies to manage this risk and it is likely the Blue Jays would have deployed such strategies.

The ownership group, given a lack of turnover of baseball executives on the club, appeared satisfied with this approach through the 1980 season. However, the Jays, winners of 54 games in 1977, had only risen to 67 wins by 1980 and attendance had fallen from 1.7 million to 1.4 million. Further, baseball was facing labor issues culminating with the 1981 player strike. Bavasi attempted to address ownership concerns about the franchise with a lengthy address in January 1981.33

- The Blue Jays are one of a few remaining clubs attempting to make a profit and win games by developing players and trading for others.

- For long-term competitiveness, we need to start spending more lavishly to recruit better players and bind our younger players, so they can’t escape through free agency.

- This spending pattern, given present ticket pricing policies and income patterns, makes meeting the profit objective very questionable.

- The Board needs to choose between major price adjustments or accept substantial cash losses until the club performs well enough to attract high attendance.

- Average player payroll has increased at a rate of nearly 30 percent per year for each of the last four years with no end in sight.

- Ticket prices and other revenue increases have not kept pace.

- When Toronto first obtained a franchise, business plans were based on the major leagues controlling the economic environment supported by the player reserve system.

- Beginning in 1976, an arbitration decision and a new union contract has created a virtual open player market.

- The impact on the Blue Jays has seen the 25-man payroll increase from $850,000 in 1977 to $2 million in 1980.

- The choices, higher ticket prices, not knowing what the market will bear; or limiting investment in talent and creating a public impression that management is not trying to win, could both lead to a fall in attendance.

By the summer of 1981, Bavasi began to prepare his fall report to the board, aware of growing ownership discontent with the direction of the ballclub. Attendance was falling, the team finished the season with a .349 winning percentage while Bavasi had previously projected that the team would be a .500 ballclub by 1980.34 And a midseason strike had soured many baseball fans. The report cited four economic realities and four budget options.35

Economic Realities

- Of the five new owners of ballclubs in the past 18 months, three (White Sox, Cubs, and Mariners) have not shown player-spending restraint and it seems unlikely the existing big spenders will start to show restraint.

- Assuming the 1981 season had been played in full, the Blue Jays, with a payroll of $2.5 million, would have realized a profit of $1.7 million if attendance had met expectations for the unplayed games; however, if the Blue Jays had the average major-league payroll of $4.9 million, at the same attendance level a loss of $700,000 would have been incurred.

- The foreign exchange rate to the US dollar hurts profitability.

- Poor stadium lease terms (i.e. 16.2 percent of concessions and no beer sales) also hurt the bottom line.

The impact of these economic realities, the report said, is that increased spending on high-profile players, assuming they meet performance expectations and weather permitting, would lead to a substantial financial loss despite achieving a better won-lost record. A better record would increase attendance and a better local television contract; however, these increased revenues would be insufficient to cover the increased payroll cost. On the contrary, a failure to invest in better players would create a public confidence problem and a decrease in attendance would also have a negative impact on profits.

Budget 1

No major change to roster and a reduction of the farm system from six teams to five. Result, profit $600,000 with attendance holding at 1.4 million.

Budget 2

No major change to the roster and maintaining the farm system at six teams. Result, profit $400,000, with attendance holding at 1.4 million and future team advancement accelerated by results from maintaining the extra farm team.

Budget 3

Acquire two or three veteran players through trade, purchase or waiver claim and maintain the six farm teams. Result, break-even based on a slight increase in attendance.

Budget 4

Acquire two veteran players through trades, sign two free agents and maintain a farm system of six teams. Result, $1.3 million loss despite a 300,000 increase in attendance.

Bavasi recommended budget 3. However, due to friction between key parties in the front office, Bavasi resigned effective December 1981.36 The internal friction within management had been building for some time. In 1981 Bavasi advised Blue Jays board vice chair Peter Hardy that Paul Beeston, the team accountant and the club’s first hire, had resigned. Hardy recalled that he had had growing concerns about Bavasi and his management style and requested an exit interview with Beeston. A reluctant Beeston, after a lot of probing, stated his concerns. “Beeston let loose, painting a picture of a tyrannical boss, a terrified, demoralized staff, and others on the verge of leaving. Among the latter, Beeston told Hardy, was Pat Gillick, who would soon follow him out the door if Bavasi remained in place. “The killer,” Hardy said, “was that he told me that Gillick shared the same view.”37 As Hardy recalled, the choice was we keep two and lose one or keep one and lose two.

Ownership did choose to invest long-term, following budget 4, and financial rewards were eventually realized. In 1982, the first year of Bobby Cox as manager, performance improved (75-84) although attendance fell to 1.3 million. On July 30, 1982, the Ontario government finally allowed beer to be sold at the ballpark on a trial basis.38 There were conditions attached: Beer could be sold only at concession stands, with a maximum of two per sale, and no beer vendors were allowed in the stands. Further, if there were too many alcohol-related problems, permission would be revoked. The media questioned how many fans would be willing to pay $1.75 a cup, a concern that proved unfounded.

News reports from that era do not refer to public lobbying efforts to lift the beer ban. The extent of behind-the-scenes lobbying is unknown because of Cabinet confidentiality. Amendments to the The Liquor Licence Act of Ontario in 1990 allowed the sale of alcohol at professional sporting events in the province.

SkyDome

Exhibition Stadium was intended to be a temporary facility until a domed stadium could be built. The ballpark had adequate capacity, 44,649, but seating could be uncomfortable. Only the outfield bleachers had a roof. Down the right-field line, the seats were aluminum benches.

Exhibition Stadium was intended to be a temporary facility until a domed stadium could be built. The ballpark had adequate capacity, 44,649, but seating could be uncomfortable. Only the outfield bleachers had a roof. Down the right-field line, the seats were aluminum benches.

Weather was always a concern for early- and late-season games at Exhibition Stadium. Concerns were greater as the prospect of the Jays playing in the postseason became legitimate. While summers were pleasant in Toronto — average highs between 70 and 80 degrees Fahrenheit from June through September — the average lows and highs for April (33-53), May (43-65), and October (39-44) made for some unpleasant conditions. The discomfort level was magnified by the fact that the ballpark had no cover for fans except in the north bleachers and, particularly in the spring, the warmer southerly winds were cooled by Lake Ontario, immediately south of the stadium. The phrase “cooler by the lake” is used with some frequency in spring weather forecasts for Toronto.

Official progress for construction of a domed stadium began in 1983 when Ontario Premier William Davis proposed the construction of a $150 million facility supported by all three levels of government (federal, provincial, municipal).39 After an eight-month study, a location was recommended at Downsview Park, 11 miles from downtown Toronto and adjacent to Downsview Airport, an air force base. The location was accessible by highway and public transit. However, the federal government was not interested in having a ballpark in the vicinity of the base.40 Ultimately, the Canadian National Railway offered undeveloped rail-yard land by the downtown CN Tower and the site was selected in January 1985. The site was within easy walking distance of Union Station, a major transportation hub for the Toronto subway system as well as the primary commuter and intercity railway terminal.

The federal government was also not interested in providing financing, thus necessitating a public/private partnership with a sharing of profit and risk. An August 1983 feasibility study said, “Our analysis indicates that private financing is not a viable method for the domed stadium. The main reason is projected net operating revenues are insufficient to generate positive cash flows (after debt service).”41 A 25-member corporate consortium was organized by Trevor Eyton, the CEO of Brascan and an early bidder for the team.42 Each corporate partner agreed to contribute $5 million in exchange for exclusive promotion or concession rights. To increase the potential revenue stream, the project was expanded to include restaurants, a hotel, and a health club.43 It is interesting to note that Brascan at the time was the controlling shareholder of Labatt. This meant that through the corporate ownership structure, Eyton now had a role in the ownership of the Toronto baseball franchise despite being an unsuccessful bidder in 1976.

The next task was selection of an architect. Four bidders competed for the contract to design and build the stadium, which would include a retractable roof. The award of the contract with a $225 million budget to architect Rod Robbie (six employees, zero experience in building skyscrapers, shopping malls, or convention centers) in conjunction with Canadian structural engineer Michael Allen to build the retractable roof was met with skepticism.44 From a technology standpoint, the skeptics were wrong. The roof has worked as designed since the day SkyDome opened, June 5, 1989, with a seating capacity of 50,516.

The next task was selection of an architect. Four bidders competed for the contract to design and build the stadium, which would include a retractable roof. The award of the contract with a $225 million budget to architect Rod Robbie (six employees, zero experience in building skyscrapers, shopping malls, or convention centers) in conjunction with Canadian structural engineer Michael Allen to build the retractable roof was met with skepticism.44 From a technology standpoint, the skeptics were wrong. The roof has worked as designed since the day SkyDome opened, June 5, 1989, with a seating capacity of 50,516.

Budget management for construction of the SkyDome was not a success story. The final construction cost for the dome, including interest charges, is estimated at $650 million.45 The large budget increase was not strictly related to poor project management. Plans for a hotel and health club were added during construction. Although the original agreement was for a sharing of profit and risk between the corporate consortium and the provincial government, the government ended up protecting the consortium members from the overrun losses. This ultimately led to a $300 million write-off being incurred by the provincial government.46 In 1993 the provincial government sold the SkyDome to a private company chaired by Eyton for $150 million. In 1999 SkyDome was sold again under supervision of a bankruptcy court for $80 million to Sportsco International Limited Partnership. In 2004 the current Blue Jays ownership purchased the $650 million stadium for $25 million and renamed the facility the Rogers Centre.47

The major factor for the decline in value was the accumulation of excessive debt during construction. By 1993 the debt had climbed to $400 million due to missed interest payments. This was worrisome given the cash flow generated after the Blue Jays won back-to-back World Series titles in 1992 and 1993 while drawing 4 million-plus each season from 1991 through 1993. A recalculation of cash-flow budgets indicated that the SkyDome had to be open for events 600 days per year to cover costs and generate a small profit.48

Despite the consortium purchase price at around the original stadium budget, finances did not improve. The 1998 bankruptcy filing indicated that the owners were losing $3 million a year and owed millions in back property taxes.49

An Era of Success: 1983-1993

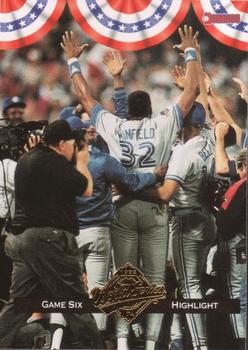

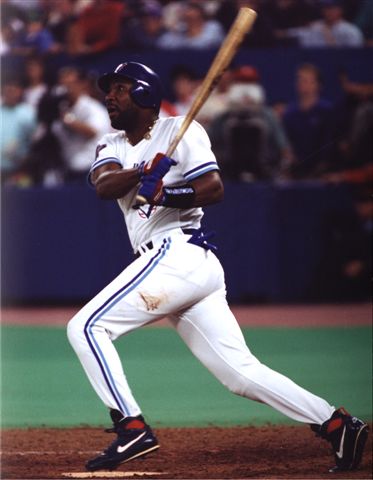

Ownership discipline to build a franchise and leave baseball decisions to experienced baseball executives like Pat Gillick paid dividends over this 11-year span. The Blue Jays were over .500 for 11 consecutive years and made five postseason appearances including back-to-back World Series titles in 1992 and 1993.

Ownership discipline to build a franchise and leave baseball decisions to experienced baseball executives like Pat Gillick paid dividends over this 11-year span. The Blue Jays were over .500 for 11 consecutive years and made five postseason appearances including back-to-back World Series titles in 1992 and 1993.

The 1985 season was the first in which more than 44 Blue Jays games were televised.50 Canada’s first Canadian sports channel, The Sports Network (TSN), had been launched September 1, 1984.51 Although TSN was owned by Labatt, it picked up only an additional 40 games beyond the existing 44 that had been broadcast the prior year.52

During this era, the Blue Jays were led by Pat Gillick on the baseball side and Paul Beeston on the business side. Beeston, an accountant and the first hire of the Blue Jays, grew to understand the business of baseball. As one Labatt executive commented, “Once he started to deal more with some of the other baseball ownership, he developed quite rapidly.”53 In 1989 ownership changed the operating structure of the Blue Jays from co-vice presidents (Beeston and Gillick) and named Beeston president.54

In August 1990, 45 percent owner Howard Webster died. According to the ownership agreement, the existing partners had the first right to purchase his ownership interest. The Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, by Canadian law, could not increase its ownership stake beyond the existing 10 percent. On November 1, 1991, Labatt purchased Webster’s stake for $67.5 million.55

The June 1989 move to the SkyDome led to greater financial success. In 1991 the second full season there, the Blue Jays became the first professional sports franchise to draw 4 million attendance in a season.56 This led to a profit of $17.5 million, up from $14 million in 1990 and $10 million in 1989.57 However, this success led to a business challenge when planning for the 1992 season. Heading into that season, the Blue Jays still had not won a World Series title and having reached the 4 million mark in attendance in 1991 meant that if the club sold out every game, attendance would rise by only 74,000.58 Management authorized additional spending, the World Series was won and in the spring of 1993, Financial World magazine estimated that the Blue Jays were tied with the Los Angeles Lakers for third most valuable franchise in sports at an estimated $115 million.59 (The top two franchises were the Dallas Cowboys and New York Yankees.)

The Blue Jays increased their payroll in 1993 and were the top spenders in baseball. As a result, the Jays calculated that they broke even for the year, thanks to the playoff revenue although Labatt realized profit through increased beer sales and broadcasting revenues.60

A Corporate Takeover — Interbrew Era: 1994-2000

Since the inception of the Blue Jays, Labatt was perceived as the owner. However, the true corporate ownership structure was much more complex and led to a major change for the Blue Jays after their back-to-back World Series titles.

The Labatt corporate history dates from 1847 when John Labatt first began making beer. The company was privately held until 1945, when it went public to raise capital for a major expansion following World War II.

In the 1970s an investment/holding company, Brascan, began increasing its stake in Labatt. By the late ’80s, Brascan owned 41 percent of Labatt, making it the controlling shareholder. In February 1993 Brascan sold its stake in Labatt for $993 million to investment dealers who in turn sold the shares to pension funds and insurance companies.61

By the fall of 1994, Labatt was struggling financially. An investment in a Mexican brewery was not doing well due to a fall in the peso. The Blue Jays had a losing record; baseball had a strike canceling the World Series; because of the strike, attendance fell to 2.9 million from 4.1 million despite an Opening Day payroll of $41.9 million, second highest in baseball; and Pat Gillick retired in October. The Blue Jays’ profit of $3 million in 1993 became a $10 million loss in 1994.62 Said Beeston, “The day that Brascan sold their interest, the company was in play, there was no major shareholder.”63

In May 1995 Onex Corporation, a private equity firm, launched a hostile takeover bid for Labatt.64 This was a concern to the Blue Jays because it was believed the takeover would be financed by pension and mutual fund advisers and the sale of Labatt assets.65 In June 1995 Labatt found a white knight in Belgian brewer Interbrew.66

Interbrew indicated it was not interested in owning the Blue Jays and asked Major League Baseball to approve temporary ownership. MLB agreed on condition that Beeston remain president of Blue Jay operations.67 Beeston recalled that his first presentation of an operational plan to the new ownership was different from the Labatt experience.68 He told a Belgian brewery representative in New York that 1995 attendance of 2.8 million for 72 home dates at an Opening Day payroll of $49.8 million (highest in baseball), and a losing record for the second year in a row had led to a $15 million loss. For 1996, Beeston said, the proposed budget was a small profit based on a $30 million payroll assuming projected attendance of 2.6 million and a Canadian dollar worth 73 cents US. The budget was approved.

Although ownership was to be temporary, Interbrew was unable to sell the Blue Jays until 2000. After two additional seasons of losing records, the Blue Jays had a winning record for the last three seasons of Interbrew ownership. That did not stem the tide of falling attendance; it declined to 1.7 million in 2000.

Rogers Communications: 2000-Present

Rogers Communications Inc. purchased a 70 percent interest in the Blue Jays from Interbrew and the 10 percent Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce interest in September 2000 for $165 million. A press release referred to the purchase being part of a North American trend to combine entertainment and communications companies. Rogers was Canada’s largest cable company and owned a sports channel. Paul Godfrey was named CEO of the Blue Jays, and remained until 2008.

In 2004, when Interbrew was purchased by Inbev, Rogers acquired the remaining 20 percent interest in the Blue Jays. As of 2019 ownership of the Blue Jays is officially listed as Rogers Blue Jays Baseball Partnership, a private company. As a result, there is little financial information publicly available. A review of the Jays won-lost record under Rogers ownership, in conjunction with payroll data published by USA Today indicates that the current ownership group does invest in the team through the winning record/losing record cycles. From 2000 through 2018, the Jays have had a winning record 10 of 19 years with two postseason appearances. In the same time frame, Opening Day payroll has fluctuated between $45.7 million and $164.1 million, ranking between 7th and 25th in baseball.

Rogers ownership included significant control over broadcast rights. Sportsnet, a second Canadian sports channel, was launched in 1998. Sportsnet was originally a joint venture, including Rogers Media as it was then known. By 2004, Rogers was the sole owner of Sportsnet and effective for the 2010 season, Sportsnet became the sole broadcaster for all 162 Blue Jays games.69

Last revised: April 1, 2019

An aerial view of Rogers Centre, home of the Toronto Blue Jays, circa 2012. (Creative Commons 2.0 image by Richie Diesterheft)

Notes

1 William Humber, Diamonds of the North (Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press, 1995), 208.

2 Maxwell Kates and Bill Nowlin, eds. Time for Expansion Baseball (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2018), 279.

3 Intercounty Baseball League, 100 Seasons Strong (Self-published, 2018), 199, describes the league as “Southern Ontario’s top independent baseball circuit.”

4 Stephen Brunt, Diamond Dreams: 20 Years of Blue Jays Baseball (Toronto: Viking, 1996), 17.

5 Brunt, 17.

6 Brunt, 18.

7 Kates and Nowlin, 280.

8 Ibid.

9 Helena Moncrieff, “Sydney Cooper Eng.,” Canadian Jewish News Spotlight: 2.

10 Brunt, 20.

11 Moncrieff, 7.

12 Brunt, 26.

13 Brunt, 21.

14 Brunt, 12.

15 Brunt, 15.

16 Brunt, 21.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Brunt, 22.

20 Ibid.

21 Kates and Nowlin, 281.

22 Brunt, 33.

23 Brunt, 35.

24 Kates and Nowlin, 282.

25 Brunt, 47.

26 The Sporting News, April 3, 1976: 28.

27 Brunt, 19.

28 Brunt, 61.

29 Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Archives, March 23, 1977.

30 The Sporting News, April 9, 1977: 38.

31 The Sporting News, April 26, 1980: 32.

32 Brunt, 66.

33 Brunt, 109.

34 Brunt, 117.

35 Brunt, 118.

36 Brunt, 133.

37 Brunt, 131.

38 CBC Archives, July 30, 1982.

39 Brunt, 150.

40 Ibid.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid.

43 Brunt, 151.

44 John Mays, “Designed SkyDome as ‘a Pleasure Palace for the People,’” Globe and Mail (Toronto), January 6, 2012.

45 Ibid.

46 Brunt, 151.

47 Marcus Gee, “SkyDome’s Legacy: Not with My Money, Never Again,” Globe and Mail, June 3, 2009.

48 CBC Archives, February 9, 2011.

49 CBC Archives, November 26, 1998.

50 The Sporting News, April 9, 1984: 30.

51 History of Canadian Broadcasting, May 2014.

52 The Sporting News, April 8, 1985: 36.

53 Brunt, 191.

54 Brunt, 192.

55 Brunt, 215.

56 Brunt, 212.

57 Brunt, 234.

58 Brunt, 235.

59 Brunt, 283.

60 Ibid.

61 Brunt, 297.

62 Brunt, 298.

63 Brunt, 297.

64 Derek Decloet, “At Labatt, They Miss the Belgians,” Globe and Mail, September 15, 2006.

65 Jacquie McNish, “Strike 3 for Gerry Schwartz,” Globe and Mail, January 19, 2001.

66 Decloet.

67 Brunt, 299.

68 Brunt, 319.

69 2010 MLB Advanced Media, May 20, 2010.