Tugerson v. Haraway: Civil Rights and the Cotton States League

This article was written by John J. Watkins

On July 13, 1953, officials from the Cotton States League and its eight teams were enjoying cocktails and dinner at the Willow Room in Hot Springs, Arkansas, prior to the annual all-star game scheduled for that evening. The festive occasion was interrupted when a United States marshal arrived to serve papers in a $50,000 civil rights suit against the league, its president, and the clubs.1 Filed earlier that day in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Arkansas, Hot Springs Division, the suit alleged that the plaintiff, an African American pitcher named James C. Tugerson, had been excluded from the all-White league because of his race.2

On July 13, 1953, officials from the Cotton States League and its eight teams were enjoying cocktails and dinner at the Willow Room in Hot Springs, Arkansas, prior to the annual all-star game scheduled for that evening. The festive occasion was interrupted when a United States marshal arrived to serve papers in a $50,000 civil rights suit against the league, its president, and the clubs.1 Filed earlier that day in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Arkansas, Hot Springs Division, the suit alleged that the plaintiff, an African American pitcher named James C. Tugerson, had been excluded from the all-White league because of his race.2

Six years after Jackie Robinson’s historic debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, only a few Black athletes toiled in the minor leagues of the segregated South, enduring innumerable indignities.3 Two leagues had no African American players: the Class AA Southern Association and the Cotton States League, a Class C circuit with four teams in Mississippi, three in Arkansas, and one in Lousiana.4 Barred from the CSL, Tugerson fought back in a court of law, even though doing so may have adversely affected his chances of reaching the major leagues.

On February 6, 1953, Tugerson signed a contract for $250 per month with the Hot Springs Bathers, a member of the Cotton States League since 1938.5 His younger brother Leander agreed to a similar deal. Both had previously pitched for the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League and decided to sign with Hot Springs on the advice of Brooklyn catcher Roy Campanella. The Bathers formally introduced their new players on March 28, the day after their contracts had been approved by George Trautman, president the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues.6

Within days of the annoucement, the events giving rise to Jim Tugerson’s lawsuit began to unfold. On April 1, Mississippi Attorney General J.P. Coleman told the press that integrated athletic competition would violate the “public policy” of his state.7 Five days later, the Cotton States League, acting through its president and directors, terminated the Hot Springs franchise “as a matter of survival.”8 At a closed door meeting on April 14, the league readmitted the Bathers and approved the club’s new majority owner9 on the condition that the Tugersons be removed from the roster.10 The Bathers acquiesced and optioned the two players to Class D Knoxville on April 20, the day before the CSL season began.11 A month later, however, the club desperately needed pitchers and recalled Jim Tugerson.12 His stay in Hot Springs was brief. The Bathers returned the big right-hander to Knoxville after league president Al Haraway ordered that the first game he was to pitch be forfeited for using an ineligble player.13

Before leaving Hot Springs, Tugerson sought legal advice about the possibility of a federal civil rights suit against Haraway and the Cotton States League, claiming that the president had denied him the right to play in the league on the basis of race.14 “It is strictly one man, Haraway,” Tugerson told a Knoxville sports writer a few days later. “He just won’t let me play because I am a Negro.”15 Previously, the Bathers owners had charged Haraway with engineering the club’s ouster from the league: “We can’t see where President Haraway, because of his personal feelings, can ramrod us out of the league on the segregation question.”16

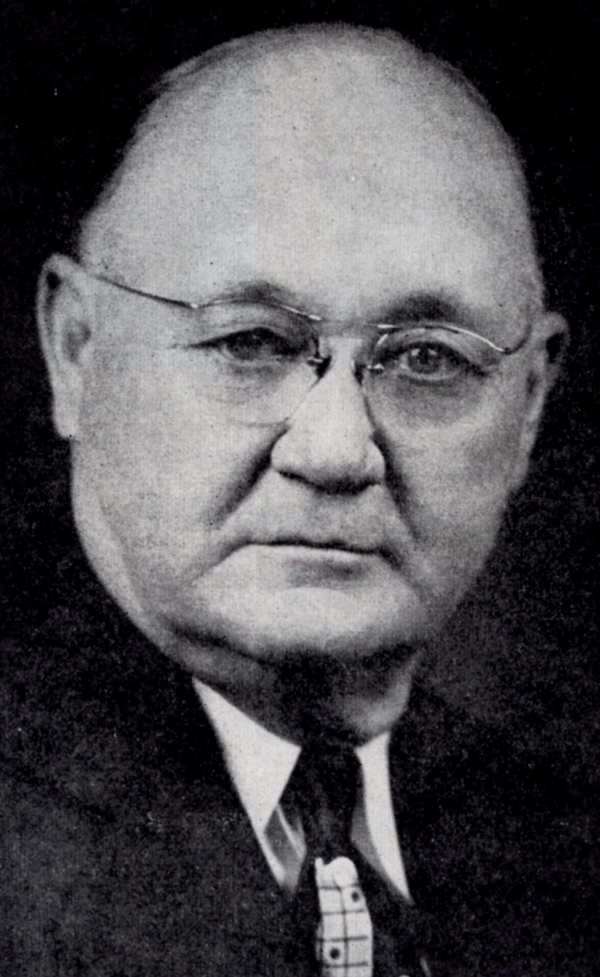

The 67-year-old Haraway, a cotton planter, owned Catron Plantation in the rich bottom land of the Mississippi River about 35 miles southwest of his home in Helena, Arkansas. He was also president and general manager of the Helena Terminal and Warehouse Company, which then handled much of the area’s barge traffic on the Mississippi, and was among the founders of a Helena bank. Before his election as president of the Cotton States League in November 1948, Haraway served five years as president of the Helena Seaporters, a CSL member in 1936-1941 and 1947-1949.17

The 67-year-old Haraway, a cotton planter, owned Catron Plantation in the rich bottom land of the Mississippi River about 35 miles southwest of his home in Helena, Arkansas. He was also president and general manager of the Helena Terminal and Warehouse Company, which then handled much of the area’s barge traffic on the Mississippi, and was among the founders of a Helena bank. Before his election as president of the Cotton States League in November 1948, Haraway served five years as president of the Helena Seaporters, a CSL member in 1936-1941 and 1947-1949.17

Tugerson retained James W. Chesnutt, probably on the recommendation of one of the Bathers owners.18 A partner in a Hot Springs law firm that had been established in 1875, Chesnutt studied history and political science at Princeton before earning his law degree at the University of Arkansas. His firm’s clients included a railroad, several major insurance companies, and the state’s principal utility, the Arkansas Power & Light Company.19 One might ask why Tugerson did not seek out a Black attorney. At the time there were fewer than ten African American lawyers practicing in Arkansas; most were based in the state’s larger cities and unwilling to travel.20 The NAACP, which was well known for challenging racial discrimination in the public sector, was not then interested in pursuing matters of private discrimination.21

Chesnutt no doubt advised Tugerson that because of adverse precedent, his federal civil rights claims would not succeed at the trial court level and that an appeal to the Supreme Court would be necessary for him to prevail.22 Litigants and their counsel are free to “argue for the modification of existing law or preserve positions for presentation to the Supreme Court,”23 and Tugerson was determined to proceed even though the lawsuit might harm his chances of reaching the major leagues. Pursuing the case “was something that he had to do,” he told his Knoxville teammates, because “it might make it easier for those [Black players] who followed.”24

The suit that Chesnutt filed on Tugerson’s behalf was assigned to Judge John E. Miller, one of three federal district judges in Arkansas and the only one who served full-time in the state’s Western District. Born in southeastern Missouri in 1888, Miller moved to Arkansas in 1912 after receiving his law degree from the University of Kentucky. Early in his career, he served as a city attorney and state prosecutor. In 1930, after several years in private law practice, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from the state’s second congressional district. In 1937, a few months after beginning his fourth term, Miller won a special election to the U.S. Senate, filling a vacancy created by the death of Senator Joe T. Robinson. President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed him to the bench in 1941.25

Tugerson’s complaint named 14 defendants: Al Haraway, individually and as CSL president; the league itself, an unincorporated association; all eight member clubs; and four officials from the Mississippi teams in Greenville, Natchez, and Meridian.26 The complaint alleged that the defendants, “based solely on the fact that [Tugerson] is a member of the Negro race,” had conspired to “prevent [him] from following his lawful occupation as a baseball player,” to prevent him from “carrying out his contractual obligations,” and to “deprive [him] of equal protection of the laws.”27 This conduct, which was based on “the custom of segregation” alleged to prevail in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, was said to violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and five federal civil rights statutes.28 An amended complaint filed the following month alleged that the defendants’ actions constituted interference with Tugerson’s contractual rights, a tort under the common law of Arkansas.29

With respect to damages, the complaint alleged that Tugerson had been deprived of the “better competition available in the Cotton States League” and the “opportunities of advancement in his career as a professional baseball player” had he remained in the Class C league for the season. Further, the complaint asserted that he had been “subjected to personal and public humiliation” and had been “deprived of the right to follow his lawful occupation in the place of his choice and to carry out his contractual obligations.” On the basis of these allegations, the complaint sought actual damages of $15,000 and punitive damages in the amount of $35,000.30 In addition, the complaint asked the court to enjoin the defendants from “interfering with [Tugerson’s] contractual rights” and from “preventing [him] from playing baseball in the Cotton States League.”31

With respect to damages, the complaint alleged that Tugerson had been deprived of the “better competition available in the Cotton States League” and the “opportunities of advancement in his career as a professional baseball player” had he remained in the Class C league for the season. Further, the complaint asserted that he had been “subjected to personal and public humiliation” and had been “deprived of the right to follow his lawful occupation in the place of his choice and to carry out his contractual obligations.” On the basis of these allegations, the complaint sought actual damages of $15,000 and punitive damages in the amount of $35,000.30 In addition, the complaint asked the court to enjoin the defendants from “interfering with [Tugerson’s] contractual rights” and from “preventing [him] from playing baseball in the Cotton States League.”31

The defendants, represented by capable and well-known Arkansas lawyers,32 moved to dismiss the complaint. Their principal attack was that it failed to state a claim on which relief could be granted.33 That is, they asserted that even if the facts alleged in the complaint were true, the law did not afford Tugerson any relief. However, the defendants also raised procedural issues unrelated to the merits.

Venue was most obvious of these procedural issues, because the applicable statutes made it impossible to sue defendants from different states in one case if the plaintiff asserted claims under federal law.34 Of the 14 defendants, venue was clearly proper only as to the four who resided in Arkansas: CSL president Haraway; Curtis Kinard, sole proprietor of the El Dorado club; and the Hot Springs and Pine Bluff clubs, both Arkansas corporations.35 Venue potentially existed as to the clubs from Mississippi and Louisiana, which as corporations “resided” in Hot Springs Division of the Western District of Arkansas if they were doing business there,36 but the court likely lacked personal jurisdiction over them.37

As a practical matter, however, these matters were of little importance because venue was proper as to Haraway, over whom the court had personal jurisdiction because he was domiciled in Arkansas.38 Tugerson clearly viewed Haraway as the primary wrongdoer in the case and sued him as an individual as well as in his capacity as the league’s president. A judgment for damages would presumably be paid out of Haraway’s own pocket unless it was covered by insurance, and an injunction against him would likely assure Tugerson’s eligibility to play in the CSL.39

On September 11, 1953, four days after Tugerson, with 29 wins, led the Knoxville Smokies to the championship of the Mountain States League,40 Judge Miller issued a 23-page opinion and an accompanying order. He dismissed Tugerson’s federal civil rights claims but, with respect to some defendants, kept alive the portion of the case based on Arkansas law for interference with contractual rights.41 However, the judge dismissed the state law claim against the Bathers, as the club had the right under its contract with Tugerson to option the pitcher to Knoxville.42 In addition, he dismissed this claim for improper venue with respect to the CSL and the four officials from Mississippi clubs.43

In considering the defendants’ motions to dismiss Tugerson’s civil rights claims for failing to state a claim on which relief could be granted, Judge Miller was required to treat as true all facts alleged in the complaint.44 After setting forth those facts in some detail, he first focused on the Fourteenth Amendment and the statute under which a claim for its violation is brought, Section 1983 of Title 42 of the U.S. Code. As it stood in 1953, Section 1983 provided that any person “who, under color of any statute, regulation, custom or usage, of any State or Territory subjects … any citizen of the United States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured.”

“Repeatedly the courts have held that the Fourteenth Amendment protects the individual against state action,” Judge Miller wrote, “but affords no protection against wrongs done by [private] individuals.”45 To come within the purview of the Amendment and Section 1983, “a person must show that his rights were violated by someone acting under ‘color’ or ‘pretense’ of law.”46 Assuming that there was a “custom of segregation” in Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana that “amounted to a law,” he continued, “said law could be enforced only by duly qualified officers and officials of the States.” Because the defendants had “no authority from the States to do any of the acts complained of by plaintiff, the action they took … was not under color of law and plaintiff has no cause of action against them.”47

With respect to the contention that the defendants had prevented Tugerson from “following his lawful occupation as a baseball player” and “carrying out his contractual obligations,” Judge Miller relied on the Supreme Court’s 1906 decision in Hodges v. United States.48 The question in that case, he wrote, was whether an African-American citizen has “a right secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the United States to work at any particular occupation or calling … free from injury, oppression, or interference on the part of individual citizens, when the motive for such injury, oppression, or interference arises solely from the fact that such laborer is a colored person of African descent.” The Supreme Court “answered that question in the negative,” he went on, by ruling that “the Thirteenth Amendment merely covered slavery and involuntary servitude and was not broad enough to protect work or contract rights” such as those Tugerson claimed.49

As for the conspiracy claims, the Supreme Court had two years earlier construed the principal civil rights conspiracy statute, 28 U.S. Code § 1985(3), as requiring state action and therefore not reaching conspiracies of private citizens. Judge Miller quoted at some length from that case, Collins v. Hardyman,50 as well as from a federal appellate court decision applying it.51 He did not consider the other conspiracy statute, 28 U.S. Code § 1986. Because liability under that statute is dependent upon a valid claim under Section 1985, however, it would not have afforded a basis for relief.52

At this point, there was little left of the case. While the claim under Arkansas law survived, questions remained as to all but two of the remaining defendants, Haraway and the Pine Bluff club. Judge Miller postponed consideration of whether the Mississippi and Louisiana clubs were subject to personal jurisdiction under an Arkansas statute applicable to out-of-state corporations doing business in the state and, if so, whether venue was proper as to them.53 Another issue was whether service of process on the El Dorado club, which had been ineffective, would be made.54

These matters were never addressed. On December 1, the Hot Springs Bathers, who held Tugerson’s rights, sold his contract to the Dallas Eagles of the Class AA Texas League.55 With the CSL behind him and the likelihood of success on appeal uncertain, Tugerson directed his lawyer to drop what was left of the case and to forego appellate review of Judge Miller’s ruling on the civil rights claims. On December 8, James Chesnutt filed a motion to voluntarily dismiss the case with prejudice, meaning that it could not be refiled. Later that day Judge Miller signed a final order of dismissal.56 In the nation’s capital, the U.S. Supreme Court was hearing oral arguments in Brown v. Board of Education.57

The landmark Brown decision was issued the following May,58 and thereafter civil rights law underwent significant changes. In 1968, the Supreme Court overruled Hodges v. United States, rejected its constricted reading of the Thirteenth Amendment, and validated a statute banning private discrimination in the sale or rental of property.59 Seven years later, the Supreme Court approved lower court cases that extended the 1968 decision to a companion statute, on which had Jim Tugerson relied, prohibiting discrimination in the making and enforcement of contracts.60 By the time these cases were decided, however, Congress had enacted a sweeping new statute — the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — which, among other things, prohibited racial discrimination by private employers.61

As these developments make plain, Jim Tugerson’s lawsuit was ahead of its time. Whether it harmed his chances of advancing to the major leagues is a matter of speculation. His age surely worked against him — he turned 30 soon after signing with the Bathers — as did the informal quota system in the 1950s that kept the number of Black major leaguers to a bare minimum.62 With these two strikes against him, the lawsuit may have been the third. It is not difficult to imagine major-league general managers, all of whom were White, looking askance at a black pitcher who had the audacity to sue a league, its president, and its member clubs.

Acknowledgments

This article was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Jeff Findley.

Sources

All sources are shown in the notes.

Photo credits:

Jim Tugerson: Hot Springs (AR) Sentinel Record, March 31, 1953

Al Haraway: Friend, J.P., Cotton States League Golden Anniversary, 1902-1951 (Helena, AR: National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, 1951)

Judge John E. Miller: University of Arkansas Libraries, Special Collections

Notes

1 “$50,000 Suit is Filed Against CSL by Negro Pitcher,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, July 14, 1953: 1.

2 James C. Tugerson v. Al Haraway, et al., Civ. No. 558, U.S. District Court, Western District of Arkansas, Hot Springs Division (July 13, 1953) (hereafter cited as Tugerson v. Haraway). Records from civil cases in this court between 1940 and 1975 are housed at the National Archives facility in Fort Worth, Texas.

3 See generally Bruce Adelson, Brushing Back Jim Crow: The Integration of Minor-League Baseball in the American South (University of Virginia Press, 1999).

4 The Mississippi teams were the Greenville Buckshots, Jackson Senators, Meridian Millers, and Natchez Indians. Arkansas was represented by the El Dorado Oilers, Hot Springs Bathers, and Pine Bluff Judges. The lone Louisiana club was the Monroe Sports.

5 A copy of the contract is attached as an exhibit to the plaintiff’s complaint in Tugerson v. Haraway.

6 “Bathers Set CSL Precedent by Signing 2 Negro Hurlers,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, March 29, 1953: 11; “Bathers’ Two Negro Hurlers Seek Chance to Prove Theselves as Players,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, March 31, 1953: 8.

7 “Mississippi Official Says Public Policy Would Cause Ban of Bathers’ 2 Negroes,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, April 2, 1953: 18; “Negroes Can’t Play Baseball in CSL,” Jackson (Miss.) Clarion-Ledger, April 2, 1953: 1; “Negro Players Barred,” New York Times, April 2, 1953: 36. No statutes prohibited integrated sports, but the state constitution mandated segregated schools and made interracial marriage unlawful. Mississippi Constitution of 1890, Art. 8, § 207; Art. 14, § 263. Coleman, who was elected governor in 1955, did not issue a formal opinion on the question.

8 “Bathers Ousted from CSL Over Negro Player Issue,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, April 7, 1953: 1; Wayne Thompson, “Hot Springs Loses Membership in CSL; Vicksburg Possibility,” Jackson (Miss.) Clarion-Ledger, April 7, 1953: sec. 2, 1; “League Throws Out Club with 2 Negro Pitchers,” New York Times, April 7, 1953: 36. The Bathers appealed this action, taken at an April 6 meeting in Greenville, Mississippi, to George Trautman of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues. On April 15, Trautman ruled that the Hot Springs franchise had been wrongfully terminated because the league had not followed the procedures set out in its constitution. But even if it had done so, he said, termination of the franchise would have been improper because employment decisions are for individual clubs to make and “the employment of Negro players has never been, nor is now prohbitied by any provision” of the National Association Agreement or other minor-league rules. “Minor League Czar Says Bathers Can Use Negro Players,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, April 16, 1953: 1; “Trautman Says Hot Springs Forfeiture Not Valid,” Jackson (Miss.) Clarion-Ledger, April 16, 1953: sec. 2, 2; “Ouster of Hot Springs Invalid, Says Trautman,” Miami Herald, April 16, 1953: 2B.

9 Approval of the ownership change was required by the league constitution. The club had been owned by A.G. “Gabe” Crawford, a Hot Springs druggist, and Tom Stough, a former college player who owned a cold storage plant, with Crawford holding the majority interest. Lewis Goltz, a local jeweler, purchased Crawford’s stock a few days before announcement of the Tugerson signings. H.M. Britt, the owner of a Hot Springs hotel, and his brother Garrett had previously acquired Stough’s shares. “Goltz Replaces Crawford As Co-owner of Bathers,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record (March 22, 1953): 14; Don Duren, Bathers Baseball: A History of Minor League Baseball at the Arkansas Spa (Maitland, Fla.: Xulon Press, 2011), 291, 315. In June, Goltz transferred his stock in the club to the Britt brothers. “Britt Named Bathers’ President; No Decision Made on Two Negroes,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record (June 11, 1953): 9.

10 The terms of the agreement readmitting the Bathers remained secret until the following month. After the April 14 meeting in Greenville, league president Al Haraway said only that the CSL would open the season “with its present eight members” on April 21, as scheduled. “Bathers to Remain in CSL; No Other Comment Comes from League Meeting,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, April 15, 1953: 13; “CSL To Open With 8 Clubs, Says Haraway,” Jackson (Miss.) Clarion-Ledger, April 15, 1953: sec. 2, 1; “Hot Springs Reinstated,” New York Times, April 15, 1953: 42.

11 “Bathers Option Negro Players to Knoxville,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, April 21, 1953: 7; “Hot Springs Team Trades Negro Players,” Jackson (Miss.) Clarion-Ledger, April 21, 1953: 1; “2 Negro Stars Optioned,” New York Times, April 21, 1953: 34.

12 “Negro Pitcher Recalled by Bathers; Will Hurl Tonight,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, May 20, 1953: 11; “Hot Springs Recalls Tugerson; May Hurl Against Sens,” Jackson (Miss.) Clarion-Ledger, May 20, 1953: sec. 2, 1. Leander Tugerson continued to pitch for the Smokies until suffering an arm injury that ended his season and his career in Organized Baseball. “L. Tugerson Out for Season,” The Sporting News, June 17, 1953: 36; Adelson, Brushing Back Jim Crow, 117.

13 “Bathers Ordered to Forfeit Game Because of Negro,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, May 21, 1953: 1; “Ump Forfeits Game To Jackson After Negro Put In Lineup,” Jackson (Miss.) Clarion-Ledger, May 21, 1953: sec. 1, 1; “CSL Controversy Cools Off As Spas Ship Player,” Monroe (La.) News-Star, May 22, 1953: 13; Emmett Maum, “Forfeit Over Use of Negro Revives Hot Springs Row,” The Sporting News, May 27, 1953: 13. Haraway claimed that the Bathers’ use of Tugerson would violate the April 14 agreement by which the club was readmitted to the league. See note 10. The Bathers challenged the forfeit, and on June 5 George Trautman set it aside and ordered that the game be rescheduled. He declared that the agreement conditioning the Bathers’ readmittance on dropping the Tugersons was not valid for the same reasons he set out in his April 15 ruling: each club is free to sign any player of its choice, regardless of race or color. Haraway appealed the decision to the National Association’s executive committee, which upheld Trautman. But the delaying tactic ensured the game would not be rescheduled and prevented the Bathers from bringing back Tugerson. “CSL ‘Pact’ Ruled Illegal; Bathers May Recall Negro,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, June 7, 1953: 12; “Game Forfeited Over Negro Pitcher Ordered Replayed,” The Sporting News, June 10, 1953: 11; “Cotton States Head Appeals Reversal of Forfeit Ruling,” The Sporting News, June 17, 1953: 35; “Tugerson Returns To Knoxville Today; Bathers Give Up Efforts To Play Him,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, July 17, 1953: 14; “Trautman Upheld in CS Ruling,” Shreveport Times, August 12, 1953: 12.

14 “Negro May File Suit Against Baseball Loop,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, May 22, 1953: 15; “Negro Hurler Sent Back to Knoxville; Plan[s] Suit,” Jackson (Miss.) Clarion-Ledger, May 22, 1953: sec. 2, 2; “Baseball Forfeit May Land in Court,” Detroit Free Press, May 22, 1953: 26.

15 Harold Harris, “Sports Static,” Knoxville Journal, May 31, 1953: B4.

16 “Bathers Ousted from CSL Over Negro Player Issue,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, April 7, 1953: 1 (joint statement of Lewis Goltz, Garrett Britt, and H.M. Britt).

17 John L. Ferguson, Arkansas Lives (Hopkinsville, Ky.: Historical Record Association, 1965), 213; J.P Friend, The Cotton States League, 1902-1951 (Blytheville, Ark.: Cotton States League, 1951), 8; “Haraway Named Head of Cotton States Loop,” Camden (Ark.) News, November 22, 1948: 6; “Al Haraway Dies Last Night In Helena Hospital,” Helena (Ark.) World, December 11, 1962: 1.

18 Henry Britt, son of Bathers minority owner H.M. Britt, practiced law in Hot Springs and was certainly well acquainted with Chesnutt.

19 “Retired Judge, Civic Leader Dies at 72 in Hot Springs,” Arkansas Gazette, January 1, 1989: 4B; Martindale-Hubbell Law Directory, Vol. 1 (Summit, N.J.: Martindale-Hubbell, Inc., 1953), 90.

20 Judith Kilpatrick, There When We Needed Him: Wiley Branton, Civil Rights Warrior (Fayetteville, Ark.: University of Arkansas Press, 2007), 54.

21 Constance Baker Motley, Equal Justice Under Law: An Autobiography (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998), 131-32.

22 The Supreme Court had long held that the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits discrimination by state actors, not by private persons or businesses — e.g., Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883). Furthermore, the statute under which an equal protection claim would be asserted, 42 U.S. Code § 1983, excluded purely private conduct, as it imposed liability on persons who acted “under color of” state law in violating another’s federally protected rights. In addition, the Supreme Court had held that the power of Congress to enforce the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery and has no state action requirement, was limited to conduct that actually enslaved a person. Hodges v. United States, 203 U.S. 1 (1906). In that case, a group of White men had terrorized several black sawmill workers, forcing them to leave their jobs. The men were convicted under a under a federal criminal statute for preventing the workers from exercising their rights under 42 U.S. Code § 1981 “to make and enforce contracts” on the same basis as Whites — in this instance, to contract for their employment. The Supreme Court reversed the convictions, stating that “no mere personal assault … operates to reduce the individual to a condition of slavery.” 203 U.S. at 18.

23 Nisenbaum v. Milwaukee County, 333 F.3d 804, 809 (7th Cir. 2003). A good example is Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968), in which a married couple claimed that the defendant, a real estate developer, had refused to sell them a house because the husband was black. They alleged a violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1982, which gave all citizens the same rights as Whites “to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property.” The district court dismissed their complaint, and the court of appeals affirmed. The Supreme Court reversed the lower courts, overruled its previous decision in Hodges v. United States, 203 U.S. 1 (1906), and held that the plaintiffs were entitled to proceed under Section 1982.

24 R.S. Allen, Schoolboy: Jim Tugerson, Ace of the ‘53 Smokies (West Conshohocken, Penn.: Infinity Publishing, 2008), 74.

25 Andrew R. Dodge and Betty K. Koed (eds.), Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774-2005 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2005), 1586; “John E. Miller, Former U.S. Senator, Longtime Judge, Dies,” Arkansas Gazette, February 1, 1981: 14A. As prosecuting attorney, Miller played a role in a sordid chapter in Arkansas history. In the fall of 1919, upwards of 200 African Americans and five White men were killed in mob violence near the small town of Elaine in Phillips County, which borders the Mississippi River. The grand jury in Helena, the county seat, indicted more than 100 African American men with crimes ranging from nightriding to murder. Many had their charges dismissed, but 65 pled guilty after 12 men were convicted of murder by all-White juries and sentenced to death. The trials lasted less than an hour, the court-appointed defense lawyers, all of whom were White, did little on behalf of their clients, and jurors deliberated for minutes. All twelve were ultimately freed following appeals to the Arkansas Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court. See Ware v. State, 146 Ark. 321, 225 S.W. 626 (1920); Ware v. State, 159 Ark. 540, 252 S.W. 934 (1923); Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U.S. 86 (1923); Richard C. Cortner, A Mob Intent on Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1988); Grif Stockley, Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Race Massacres of 1919 (Fayetteville, Ark.: University of Arkansas Press, 2001).

26 Complaint, Tugerson v. Haraway, 1-3. When it later appeared that the El Dorado club was operated as a sole proprietorship, Chesnutt amended the complaint to add Curtis Kinard, the owner of that team, as an individual defendant. Amended Complaint, Tugerson v. Haraway (August 27, 1953), 1. The other seven clubs were organized as corporations.

27 Complaint, Tugerson v. Haraway, 7.

28 Complaint, Tugerson v. Haraway, 7-8. The statutes were codified as 42 U.S. Code §§ 1981, 1982, 1983, 1985 & 1986 (1952) and are since unchanged, with the exception of relatively minor revisions in Section 1983. The inclusion of Section 1982 in the complaint was undoubtedly an oversight, as it provides for equal rights in the sale and purchase of property and had no application in Tugerson’s case.

Because the complaint stated claims for relief based on federal law and alleged damages of $50,000, the court had subject matter jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S. Code § 1331 (1952). Jurisdiction of the subject matter is the authority of a court to decide a particular type of case. The federal courts have limited subject matter jurisdiction, defined by Article III of the U.S. Constitution and implemented by federal statutes. Section 1331 conferred jursidiction in civil cases in which “the matter in controversy exceeds the sum or value of $3,000, exclusive of interests and costs, and arises under the Constitution, laws or treaties of the United States.” (Congress eliminated the amount-in-controversy requirement in 1980.) A separate statute granted jurisdiction, irrespective of the amount in controversy, over claims for deprivation of rights “secured by the Constitution … or by any Act of Congress providing for equal rights.” 28 U.S. Code § 1343(3) (1952). Paragraphs (1) and (2) of this statute provided for jurisdiction over an action to recover damages from conspiracies to deprive a person of his or her civil rights. These provisions remain in effect and now appear in 28 U.S. Code § 1343(a)(1)-(3).

29 Amended Complaint, Tugerson v. Haraway (August 27, 1953), 1. The Arkansas Supreme Court had long court had long allowed recovery of damages for wrongful interference with contractual relationships. E.g., Hogue v. Sparks, 146 Ark. 174, 225 S.W. 291 (1920); Mahoney v. Roberts, 86 Ark. 130, 110 S.W. 225 (1908). The court also recognized civil liability for conspiracy. E.g., Stewart v. Hedrick, 205 Ark. 1063, 172 S.W.2d 416 (1943). Although Tugerson’s suit had been brought in federal court, Judge Miller was obligated to follow these decisions to resolve the portion of the case based on state law. Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1938).

The state law claim fell within the court’s subject matter jurisdiction under 28 U.S. Code § 1332(a) (1952), which provided that district courts had jursidction “of all civil actions wherein the matter in controversy exceeds the sum or value of $3,000, exclusive of interests and costs, and is between … citizens of different states.” (The amount is now $75,000.) Tugerson was a citizen of Florida, no defendant was a citizen of that state, and the complaint alleged damages well in excess of $3,000.

30 Complaint, Tugerson v. Haraway, 8.

31 Complaint, Tugerson v. Haraway, 9.

32 The Jackson Senators, for example, retained James M. McHaney of Little Rock, a Columbia Law School graduate who, as a prosecutor at Nuremberg, sent Nazi doctors to the gallows for conducting medical experiments on concentration camp inmates. Robert M. Thomas, Jr., “James M. McHaney Dies at 76; Prosecuted Nazis at Nuremberg,” New York Times, April 26, 1995: 25. The Cotton States League and Al Haraway were represented by J. Graham Burke of Helena, a graduate of Vanderbilt Law School who specialized in commercial law and the legal issues concerning flood control along the Mississippi River. “J. Graham Burke, Helena, Dies at 70,” Arkansas Gazette, July 24, 1962: 9B. Jay W. Dickey of Pine Bluff, the lawyer for that city’s team, represented major insurance companies and had recently completed a 10-year term on the University of Arkansas Board of Trustees during which the law and medical schools had accepted their first black students. “Funerals/Deaths: Jay W. Dickey Sr., 81, Senior Law Partner in PB,” Arkansas Democrat, June 11, 1988: 4B; Martindale-Hubbell Law Directory, Vol. 1 (Summit, N.J.: Martindale-Hubbell, Inc., 1953), 112.

33 Rule 12(b)(6), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

34 Venue is the geographical area where a suit may be brought. Unlike jurisdiction, which goes to the power and authority of the court, venue requirements reflect a legislative determination that a particular location is convenient for the litigants. In 1953, a suit asserting claims under federal law could be brought only in the federal district where all the defendants resided. 28 U.S. Code § 1391(b) (1952). If multiple defendants resided in different districts of the same state, or in different divisions of the same district, the suit could be brought in any division in which any defendant resided. 28 U.S. Code §§ 1392(a), 1393(b) (1952). For venue purposes, a corporation was deemed to reside in any judicial district in which it was incorporated, licensed to do business, or doing business. 28 U.S. Code § 1391(c) (1952).

35 Tugerson’s suit was brought in the Hot Springs Division of the Western District of Arkansas. The Hot Springs club, an Arkansas corporation, was a resident of that district and division. Some courts held that a company incorporated in a given state could be sued in any federal judicial district and division in the state, given that a state certificate of incorporation recognizes the corporation’s right to conduct business throughout the state. Other courts, however, took the position that a domestic corporation could be sued only in the division where it maintained its principal office, unless it also did business in another division. Under either approach, venue as to the Bathers lay in the Hot Springs Division. Venue was proper as to the Pine Bluff club under the first approach but not necessarily under the second, which turned on the court’s application of the “doing business” test, discussed in note 36. Regardless, the Pine Bluff club could be sued in the Hot Springs Division because the Bathers resided there. 28 U.S. Code § 1393(b) (1952). That was also the case with respect to Curtis Kinard, sole proprietor of the El Dorado Oilers, and CSL president Al Haraway. Kinard lived in El Dorado, which is in the Western District but not in the Hot Springs division. Haraway lived in Helena, Arkansas, which is located in the Eastern District.

Venue was improper with respect the officials from the Mississippi clubs and to the Cotton States League. The club officials named as defendants were Robert O. May of Greenville, Tom Glennon and John Junkin of Natchez, and C.B. Rawlings of Meridian. The plaintiff’s complaint acknowledged that the men resided in those cities. Complaint, Tugerson v. Haraway, 3. The CSL was an unincorporated association with its headquarters in Greenville. Complaint, 1. Judge Miller had previously ruled, consistent with decisions by other courts, that an unincorporated association resided for venue purposes where its principal office was located. McNutt v. United Gas, Coke & Chemical Workers of America, 108 F. Supp. 871 (W.D. Ark. 1952). Years later, the Supreme Court held otherwise, ruling that an unincorporated association resides in any judicial district where it is doing business. Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad Co. v. Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, 387 U.S. 556 (1967).

36 The four Mississippi clubs and the team from Louisiana were corporations organized under the laws of those states. None had obtained a license to transact business in Arkansas. Accordingly, they would be deemed to “reside” in the Hot Springs Division of the Western District of Arkansas only if they were “doing business” there. 28 U.S. Code § 1391(c) (1952). There was no precise formula for determining the amount of corporate activity required to constitute doing business. Relevant factors included the nature and scope of the corporation’s business operations, the extent of its activities in the district, and the continuity of those activities. However, a single transaction or casual activity in the district, such as an isolated sale or limited advertising, was not sufficient. The five out-of-state teams seem to have conducted more than casual activities within the Hot Springs Division. During the course of the 1953 season, not including the playoffs, each of them played nine games in Hot Springs: three two-game series and one three-game series. “1953 Official Cotton States League Schedule,” Greenville (Miss.) Delta Democrat-Times, March 8, 1953: 7. The players, managers, and any other personnel spent at least one night in a local hotel on each trip and presumably patronized restaurants and other businesses. The visiting teams may have shared in the gate receipts, although this is not certain. Later cases involving sports teams held in similar circumstances that teams in professional leagues were “doing business” in a district when they made scheduled trips there on a regular basis. E.g., American Football League v. National Football League, 27 F.R.D. 264 (D. Md. 1961).

37 Personal jurisdiction is the power of the court to ascertain and enforce personal obligations, e.g., to decide that breach of a contract resulted in economic loss or that negligent operation of an automobile caused injury. To decide these matters and issue an enforceable judgment, the court must have jurisdiction of the person who is to be declared liable. The states have enacted statutes designed to subject out-of-state corporations the personal jurisdiction to their courts under certain circumstances, and these statutes typically apply in federal court proceedings. A 1947 Arkansas statute, since repealed, asserted personal jurisdiction over foreign corporations that “do any business or perform any character of work” in the state with respect to claims that arose from that business or work. Ark. Stat. § 27-340 (1947). Even if that statute applied to the defendants, the court was required to consider whether the exercise of jurisdiction over them would be consistent with the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The U.S. Supreme Court had held that a defendant must have “minimum contacts” with the state where the plaintiff brought suit and, except in unusual circumstances, that the plaintiff’s claim for relief must have arisen from those contacts. International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310 (1945); Perkins v. Benguet Consolidated Mining Corp., 342 U.S. 437 (1952).

The problem for Tugerson was the same under both the state and constitutional requirements: his claims did not appear to arise from the clubs’ activities in Arkansas. Each played 27 regular-season games in Arkansas in 1953, nine games against each of the three Arkansas teams. Tugerson’s claims, however, stemmed not from those contests but from action taken by the league directors at meetings in Greenville, Mississippi, on April 6 and 14. One might argue that the forfeited game in Arkansas on May 20 occurred at the direction of CSL president Haraway, an Arkansas resident, but his action was based on action taken at the April 14 meeting. See notes 8, 10, and 13.

38 Milliken v. Meyer, 311 U.S. 457 (1940).

39 A month after the suit was filed, the National Association’s executive committee upheld George Trautman’s ruling that set aside Haraway’s forfeit of the game that Tugerson was to pitch. See note 13. This decision appeared to settle the authority of individual clubs, as a baseball matter, to employ players of their choosing, regardless of race. Of course, it lacked the force of a court order such as the injunction that Tugerson sought.

40 “Knoxville Takes MSL Playoffs Over Twins,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, September 8, 1953: 15.

41 Opinion, Tugerson v. Haraway (September 11, 1953): 19. See also “Federal Judge Drops Civil Rights Portion of Negro Hurler’s Suit,” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, September 12, 1953: 8; “District Judge Rules CS Action Not a Violation,” Jackson (Miss.) Clarion-Ledger, September 12, 1953: 9; Maurice Moore, “Court Dismisses Negro Player’s Civil Rights Suit,” The Sporting News, September 23, 1953: 11. Tugerson’s initial reaction was to appeal. “I’m convinced I have a good case,” he said, “and I have authorized my lawyer to appeal Judge Miller’s decision. I believe I am right.” Tugerson loses first round will appeal,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 19, 1953: 16.

42 Opinion, Tugerson v. Haraway, 20.

43 Opinion, Tugerson v. Haraway, 20, 22.

44 Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123 (1950); Harris v. Capehart-Farnsworth Corp., 207 F.2d 512 (8th Cir. 1953).

45 Opinion, Tugerson v. Haraway, 14 (emphasis original).

46 Opinion, Tugerson v. Haraway, 16.

47 Opinion, Tugerson v. Haraway, 17.

48 203 U.S. 1 (1906).

49 Opinion, Tugerson v. Haraway, 18.

50 341 U.S. 651 (1951). The Supreme Court overruled Hardyman in Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88 (1971).

51 Opinion, Tugerson v. Haraway, 15, quoting Hardyman, 341 U.S. at 661, and Downie v. Powers, 193 F.2d 760, 760 (10th Cir. 1951).

52 Robeson v. Fanelli, 94 F. Supp. 62 (S.D.N.Y. 1950). Numerous later cases so hold. E.g., Dowsey v. Wilkins, 467 F.2d 1022 (5th Cir. 1972); Mollnow v. Carlton, 716 F.2d 626 (9th Cir. 1983).

53 Opinion, Tugerson v. Haraway, 21-22. Venue is discussed in notes 34-36, personal jurisdiction in note 37.

54 Opinion, Tugerson v. Haraway, 22. Service of process — i.e., a summons and copy of the plaintiff’s complaint — is the mechanism by which notice of the suit is given to the defendant. Without proper service, the court does not acquire personal jurisdiction over the defendant. The El Dorado club was mistakenly sued as a corporation, and service was made, ineffectively, on its business manager. Curtis Kinard, the club’s sole proprietor, was named as a defendant in an amended complaint, see note 26, but he had not been served. As Judge Miller pointed out, the dismissal of all claims against the Hot Springs club meant that “there is no properly served defendant residing in the Hot Springs Division, or the Western District of Arkansas, unless the Court should hold that some or all of the corporate defendants are doing business therein and consequently are residents thereof for venue purposes.” Opinion, Tugerson v. Haraway, 23. With respect to the venue issues, see notes 34-36.

55 “Dallas Club Buys Big Jim Tugerson,” Knoxville Journal,” December 2, 1953: 9. The deal was announced two days after former St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Paul Dean purchased the Bathers. “Paul Dean Buys Hot Springs Club,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 30, 1953: 5D.

56 Order, Tugerson v. Haraway (December 8, 1953); “Tugerson Drops Suit Against CSL,” Arkansas Democrat, December 8, 1953: 24; “Tugerson Drops Civil Rights Suit Against Cotton States,” Jackson (Miss.) Clarion-Ledger, December 9, 1953: sec. 2, 4.

57 Luther A. Huston, “Administration Urges High Court to Outlaw Segregation in Schools,” New York Times, December 9, 1953: 1.

58 Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

59 Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) (upholding 42 U.S.C. § 1982).

60 Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454 (1975) (upholding 42 U.S.C. § 1981). Sections 1981 and 1982 were both derived from the Civil Rights Act of 1866, Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, § 1, 14 Stat. 27.

61 The Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. 88-352, 78 Stat. 241. Title VII of the Act, codified at 42 U.S. Code § 2000e et seq., addresses discrimination in employment.

62 Steve Treder, “The Persistent Color Line: Specific Instances of Racial Preference in Major League Evaluation Decisions after 1947,” Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, vol. 10, no. 1 (Fall 2001): 1-30.