The Spitball and the End of the Deadball Era

This article was written by Steve Steinberg

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 23, 2003)

“We must look for some legislation before long in regard to the pitcher. We are all willing to concede that he is a plucky, determined Base Ball character, and the very fact that he is so persistent and combative makes it necessary now and then to subordinate him a little to the other men who are part of the game.” — Spalding’s Official Baseball Guide, 1909

“The fight against the predominance of the pitcher is almost as ancient as baseball itself.” — Irving Sanborn, “Consider the Pitcher,” Baseball Magazine, September 1920

Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher Burleigh Grimes demonstrates his spitball before a game at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh in 1928. Grimes was one of 17 major-league pitchers who were grandfathered in to continue throwing the spitball after it was banned in 1920. (SABR-RUCKER ARCHIVE)

1920 was a seminal year for baseball. Events had conspired to bring the Deadball Era to an end, and make way for the Lively Ball Era. This was no gradual transition: the rise in offense in 1919 (mainly in the AL) intensified and spread to the NL in 1920 and was confirmed as more than a fluke in 1921. The curtain went up on the new as quickly as it came down on the old.

On center stage was the ball. Yet the driving force was not so much what the owners ordered done to the ball by its makers as what they ordered not done to the ball by its hurlers and done with the ball by the umpires. What were commonly called “freak” pitches were the focus, and the spitball was lumped together with them in the eye of the storm. Just what impact did rule changes with these pitches have on the end of the Deadball Era? What other factors were involved?

The spitball had an enormous impact on the game since its origin in the early 1900s. One of its biggest foes, Baseball Magazine editor F. C. Lane, acknowledged its power:

It is a tricky and dangerous ball to control. But once mastered, as only a few have been able to master it, it is all but unhittable.

— “Should the Spitball Be Abolished?” June 1919

In Babe Ruth’s Own Book of Baseball, he (or his ghost- writer) explained:

The theory of the spitter is simple enough. The ball is wet on one side. Naturally that makes a slippery spot which reduces friction and gives added speed to the opposite side where friction is applied. All spitballs break down, but by turning the wet spot one way or the other, the pitcher can make the ball break in or out as he desires.

The spitter was also a psychological weapon, a powerful decoy. Spitball pitchers went through the motions of “loading up” (putting saliva on the ball) before almost every pitch by bringing the ball and glove to the mouth. They went through this ritual even when they were not “loading up,” to sow confusion in the minds of batters. Some spitballers, like Urban Shocker, threw the pitch only a few times a game, yet the batter never knew when it was coming.

Shocker is a great pitcher. But honestly I don’t know whether he is a great spitball pitcher. In nine innings today he threw exactly four spitballs. I was surprised. I expected a flock of them. But he came up with everything a good pitcher should have.

— Ed Walsh, 1924 Reach Guide

The two greatest purveyors of the pitch were Jack Chesbro and Ed Walsh. In 1904, Chesbro won 41 games for the New York Highlanders (forerunners to the Yankees). Sadly, he is most remembered for one spitter he lost control of on the final day of the season, in the ninth inning of a tie game with a runner on third base. With that wild pitch, the game and the pennant belonged to the Boston Americans, in one of Boston’s biggest wins over New York in the 20th century. Walsh led the Hitless Wonders, the Chicago White Sox, to victory in the 1906 World Series and won 40 games for them in 1908.

Discussion on whether the pitch should be outlawed goes back almost as far as the pitch itself. In 1907, Chicago White Sox manager Fielder Jones spoke out strongly against it, even though he had a star in spitballer Ed Walsh (Sporting Life, August 8, 1907). In 1909, a debate on the spitter was the feature in the Reach Guide. Baseball writers were split on whether the pitch should be banned, and some were prescient in their remarks:

While the spit ball is sloppy, dirty, and disgusting, it is, I fear, impossible to get rid of.

— W.A. Phelan, Chicago Journal

More than a decade would go by before the pitch’s foes were able to legislate its ban. Many arguments were used against it. Its unsanitary nature at the time of the deadly flu epidemic of 1918-19 certainly didn’t help its cause. Already in 1907 a Cleveland public health doctor spoke of the connection between the pitch and tuberculosis:

What would a man’s feelings be with a batted ball covered with microbes coming at him like a shot out of a gun?

— Dr. Martin Friedrich, Sporting Life, May 18, 1907

There were the fielding and throwing problems the slick ball created. There were the delays it caused, as the pitcher brought both ball and glove to his mouth before each pitch, whether he planned to throw the “wet one” or not. In an age when two-hour games are so rare, we can only chuckle at the humorous argument.

These two-hour games wore on the nerves. They made the Boss Bug [fan] late for supper and when this happened the real Boss Bug grew peeved and knocked the game for making him late for meals.

— “Scribbled by Scribes,” The Sporting News, May 20, 1920

Then there was the argument about the spitter’s impact on the arm. Such a concern was not even mentioned in the 1909 Reach debate. Chesbro and Walsh had meteoric yet tragically short careers, but in 1908 both men were still pitching effectively. Respected umpire and columnist Billy Evans spoke out passionately against the pitch in Harper’s Weekly.

I have seen a score of pitchers drop out of the majors, because of the strain placed upon their arm through using the spitball.

— May 2,1914The history of the spitball is that it has ruined many an arm of steel.

— June 13, 1914

At the same time, in the mid-teens there was a lull in great spitball pitching. It is interesting to note that there were more outstanding spitball pitchers in the 1920s than there were in the entire Deadball Era. Some observers even felt that the spitter was no longer a dominant pitch in the teens, that with the passing of Ed Walsh, it was practically eliminated.

New Ed Walshes may arise, but we much doubt . . . Big Ed was almost in a class by himself, and the moulder [sic] of men seldom duplicates such a feat.

— The Sporting News, March 15, 1917

At least as old as the spitball were “freak” pitches that involved “doctoring” the ball to change its aerodynamics. Back in the 1890s Clark Griffith created the scuff ball by using his spikes to roughen its surface. As the decade of the teens moved forward, pitchers began to develop more trick pitches: the shine ball, emery ball, paraffin ball, licorice ball, mud ball, and more. All these pitches gave the ball added and unusual movement as it approached the plate.

They were all (including the spitter) based on the concept that contrasting surfaces (of rough and smooth) affected the ball’s flight and revolution and gave it a peculiar hop, usually dropping down. These pitches brought success to their hurlers and frustration to hitters, since they were so difficult to make contact with. Once they added such a pitch to their repertoire, pitchers like Russ Ford (emery ball), Eddie Cicotte (shine ball), and Hod Eller (shine ball) became much more successful. While there were rules against some of these pitches, like the emery ball, they were not easy to enforce.

As with the spitter, artifice and deception were part of the weaponry. There was ongoing discussion whether Cicotte’s shine ball was real or simply imagined. A 1917 article called the pitch a “mythical flicker” and “mental hazard” for superstitious players (New York Times, September 26, 1917). Sportswriter Tom Meany expressed the “mind game” that pitchers used:

Batters who are always seeking to detect some sign of chicanery on a pitcher’s part sometimes become so engrossed in looking for illegal pitches that they forget to hit the legal ones.

— Baseball’s Greatest Teams, Barnes, 1949

All these pitches had an enormous effect on the confidence and thus the hitting of batters — because of what the ball did, what it might do (sail and hit the batter), and what it was reputed to do.

There were so many “doctored” pitches, surreptitiously prepared, that sentiment was building that the pitchers had gone too far. Among the owners the position was emerging that all trick pitches should be swept away. In February 1920, the Joint Rules Committee enacted laws that banned all “freak” pitches, including the spitter.

A couple of years earlier, National League President John Tener had explained his opposition to the “wet one”:

I dislike the spitball because it affords an opening to so many other illegal deliveries. An umpire must continually watch a spitball pitcher so that he does not use his spitter as a subterfuge to cover up something else.

— New York World, February 10, 1918

The Sporting News argued it would be too difficult for umpires to control “freak” pitches if the spitter were legal (September 11, 1919). Years later, shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh, whose long career spanned both the Deadball and Lively Ball Eras almost equally, explained it best:

It wasn’t the spitball exactly they wanted to ban. They wanted to get rid of all those phony pitches. All of those pitches were in the disguise of the spitter. You see, the pitchers went to their mouths, but then they might throw you a shine ball or a mud ball or an emery ball. … So as I understand it, the only way they could stop them fooling with that baseball was to bar the spitter, not let the pitcher go to his mouth.

If a pitcher didn’t go to his mouth and still threw one of those freak pitches, the umpire would know damn well the guy was doctoring the ball. That’s how they stopped it.

— Donald Honig’s The Man in the Dugout

Pitchers of the “freaks” could masquerade as spitball pitchers too easily. Every pitcher has been obliged to suffer for the sins of the freak delivery artists.

— F.C. Lane, “Has the Lively Ball Revolutionized the Game?” Baseball Magazine, September 1921

Umpire Billy Evans agreed that pitchers had only themselves to blame, with all the ways they had “doctored” the ball (St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 27, 1921). Perhaps Cincinnati pitcher Hod Eller was right when he wrote in an article entitled “Why the New Pitching Rules are Unjust”:

The world has gone mad over freak deliveries.

— Baseball Magazine, August 1920

The rule changes took place against the backdrop of rumors of a “fix” in the 1919 World Series, even though the Black Sox Scandal had not yet broken wide open. The owners had looked the other way far too often, whether the issue was gambling or emery balls. It was time for a bold and dramatic move, and they made one.

Ultimately, the rule changes were instituted to help the hitters and bring more fans into the ballparks. Washington owner-manager Clark Griffith may have turned on his former profession, but he was forthright.

Why encourage the which the pitcher has on batting? … Batting is the most interesting part of the game. It ought to be encouraged.

— “Ban the Spitter,” Baseball Magazine, July 1917

His star pitcher Walter Johnson made a remarkable admission to a New York paper just a few months after the new rule was instituted:

Hitting plays the most important role in a ball game. There is no getting away from the fact that the baseball public likes to see the ball walloped hard. The home runs are meat for the fans. ‘Babe’ Ruth draws more people than a great pitcher does. It simply illustrates the theory that hitting is the paramount issue of baseball.

— Evening Telegram, August 22, 1920

In his landmark diatribe against the spitter, F.C. Lane expressed his opposition to it:

Last, and most important of all, the spit ball hurts batting and therefore strikes straight at the heart of the game’s popularity. … The game has become one-sided; too much of a mere pitchers’ duel. Something should be done for the downtrodden batter. … One of the simplest and easiest ways to lighten the batter’s load is to throw out the spitball.

— “Should the Spitball be Abolished?” Baseball Magazine, June 1919

Simply put, it was time to swing the pendulum back toward the batter. Ironically, as hitting dominated the 1920s, Lane would become one of the most outspoken foes of what he called the “home run epidemic,” the “fever of batting which has run riot,” and the “orgy at bat” (Baseball Magazine, July 1921, August 1925, and June 1927, respectively).

It is hard to understand nowadays just how rare and special a home run was before 1920. After an eighth-inning three-run blast beat the Yankees in a 1917 game, New York writer Walter Trumbull described it this way:

There is nothing more extraordinary than a home run. No scene in melodrama can so grip the chords that thrill. … A circuit clout is the greatest transmitter of emotions. It makes smiles grow where none grew before, or smothers laughter beneath a pall of gloom.

— New York World, April 26, 1917

And in 1919, Boston’s Babe Ruth electrified the baseball world, and drew large crowds wherever he played, when he hit an almost unthinkable 29 home runs. The entire American League had hit only 96 circuit clouts the year before.

Where did the existing spitball pitchers stand? Before the winter meetings, there was still some support to protect them. Even AL president Ban Johnson, in a letter to St. Louis Post-Dispatch editor John Wray on August 31, 1919, wrote:

No great restrictions will be placed upon the spitball pitchers of the present day.

But the sentiment had shifted by the time of the February 1920 meetings in Chicago (after the 1919 World Series). Echoing the sentiment of W.H. Lanigan a decade earlier (“Into the cuspidor with the spit ball,” Reach Guide, 1909), existing spitballers were given one more year to throw that pitch and learn a replacement. By 1921, the spitter would be gone from major league baseball.

This was ominous news indeed for baseball’s spitballers. They had gotten a reprieve, but only for a year. They banded together and organized a lobbying effort. Appropriately, Spittin’ Bill Doak of the St. Louis Cardinals was one of the leaders of the group. They began to appeal to the sympathy of the writers and the fans. At the same time, their argument gave a strong hint of legal action based on an unfair labor practice by baseball’s owners. Spitballer Jack Quinn of the Yankees framed the issue:

Cutting out the spit ball after permitting me to pitch it all my life is like reaching into my pocket and taking money from me.

— New York Evening Telegram, May 20, 1920

The spitballers had a remarkable stroke of good fortune. Four members of their exclusive fraternity were in the 1920 World Series between Cleveland and Brooklyn. The Dodgers’ Burleigh Grimes was impressive with a shutout win in Game Two and a tough loss in Game Seven. The Indians’ Stan Coveleski was spectacular: three complete-game wins and only two earned runs and two walks in 27 innings. How could baseball possibly pull the rug out from two of its biggest stars? (The other two spitballers were Cleveland’s Ray Caldwell and Brooklyn’s Clarence Mitchell.)

Table 1: Grandfathered Spitballers After 1920 Ban

(Click image to enlarge)

While sentiment shifted toward these pitchers, The Sporting News remained firm in its support of the ban and accused the owners of waffling for selfish reasons.

They [owners] are unalterably opposed to doing anything for baseball or for anything or anybody else, when the act involves the loss of a dollar’s worth of baseball property to themselves.

— February 3, 1921

In the end, the owners did back down and permitted the existing spitballers to continue using the pitch. Still, the owners got what they wanted: a ban on trick pitching, no new spitballers, and protection for the familiar faces and arms that threw the “wet one.” These men were permitted to throw the pitch for the rest of their careers. Hurlers of other trick pitches faced no similar protection. In 1924, the Reach Guide tried to explain the distinction in “Passing of the Spitball Pitcher.”

Not everyone could throw a spitball. It required years of painstaking effort to master. A pitcher who had reached the major leagues with it had accomplished something. It would be unfair to throw him out with the others who tampered unfairly with the ball. So baseball held one brief for the spitter, it voted to allow him to live out his career.

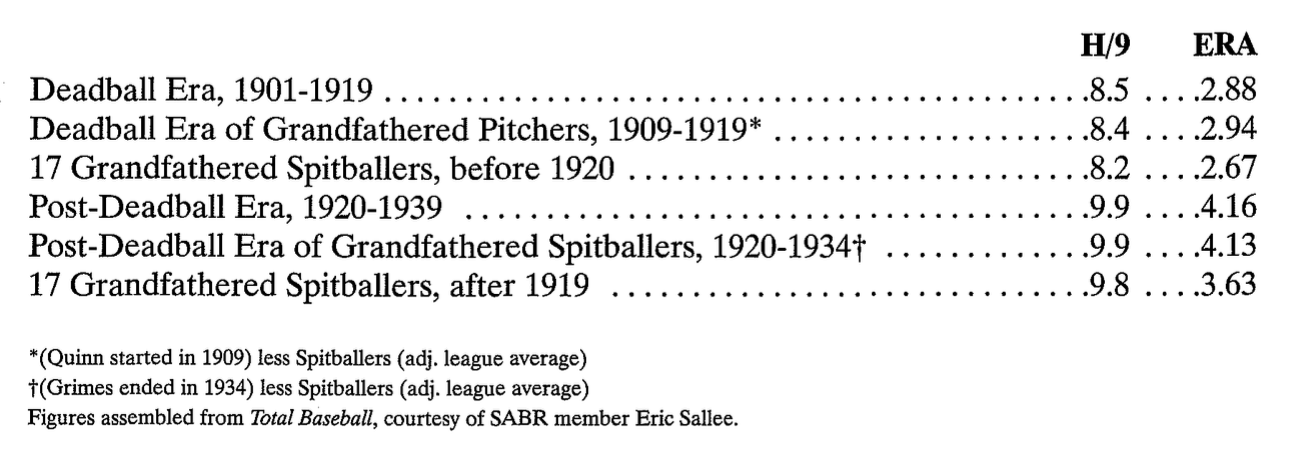

How much impact did the ban on the spitter have on the end of the Deadball Era? After all, 17 spitballers were protected, and offense still rose significantly. It is true that future spitballers were banned and, as the 1920s progressed, the spitball fraternity continued to shrink. But earned run averages and batting averages rose right away, at the start of the 1920s, not the end of the decade.

After 1919 the spitballers maintained their advantage of about 10% fewer earned runs than all major league pitchers. Yet their numbers were impacted negatively along with pitching as a whole, and the Lively Ball Era took off in 1920 in spite of these hurlers. It was simply tougher to pitch after 1919.

Clearly, factors other than the banning of the spitter (beyond the “club” of 17) drove the new age of hitting. In 1920, batting averages and home runs began to climb dramatically in both leagues. The 1920s saw “The Reign of the Wallop:”

Batting is king. All other departments of the game are now subordinate subjects. The increased crowds at the present games strongly indicate that the public likes the present era of free and fancy swatting. … And if the public prefers the new game, the magnates prefer it.

— W.R. Hoefer, Baseball Magazine, July 1923

First, the ban on freak pitches other than the spitter (as well as a ban on new spitballers) had an enormous impact on the game. Hitters faced less effective pitchers, with fewer weapons at their disposal. Moreover, for years pitchers had ignored mastering the curveball, instead depending on “trick” pitches. Youngsters took the popular and easier route of learning the “latest” new pitch. They had “discarded the twirler’s best weapon, a fast-breaking curve” (umpire and syndicated columnist Billy Evans, The Times, St. Louis, May 20,1924). Pitchers were now in desperate straits — they had no pitch to fall back on.

In the 1920s there was much discussion about the absence of the curveball and its slow return to the game. NL president John Heydler spoke of the time would be needed after the rule changes, for and minor league pitchers to develop “legitimate pitching devices” like the curve and change of pace (Evening Telegram, New York, July 8, 1920).

Just before former Yankee manager Wild Bill Donovan was killed in a train wreck in December 1923, his last conversation with baseball colleagues was widely publicized: he was lamenting the dearth of good curve ball pitchers in the game. A few months later, Baseball Magazine discussed this issue in a lengthy article by Irving Sanborn entitled “The Decline of Curve Ball Pitching” (April 1924).

In case the new rules were not clear enough for future major league pitchers, emphasis was added. Immediately after Rule 30, Section 2, Spalding’s Official Guide (1921) noted:

Young pitchers should take special cognizance of this section. From now on, it will be foolish for pitchers to experiment with freak deliveries … absurd for a beginner to waste his time on anything except straight baseball …

Ty Cobb gave his perspective on the history of pitching in 1925:

Pitching has gone through three periods. First came the pitchers who developed the fastball and curve. Then came along the spit-ballers [sic]. Finally there were the trick pitchers such as Russell Ford with his emery ball. They have barred all that and we are back at the beginning again. It is going to take the pitchers of today some time to develop the curve to its full efficiency again.

— New York Evening Post, August 11, 1925

Furthermore, the increased confidence of hitters should not be overlooked. Because many of the trick pitches were hard to control, there was an intimidation factor at play: batters had been afraid of being hit. Now most of the tosses that used to worry batters and make them look foolish were part of the past. Also, is it possible that the disruption of World War I, with the dramatic cutback in the number of minor-league teams, may have hurt pitchers more than it impacted hitters?

The Lively Ball Era is somewhat of a misnomer. Despite all the rumors and anecdotal evidence about a “juiced” or “rabbit” ball, it is generally accepted that the owners did not order a livelier ball and that the ball itself was not altered. The words of NL President John Heydler, a man of impeccable integrity, that there was no change in the ball’s construction, were confirmed by numerous independent tests. (One of the most widely publicized was that done by Columbia University chemistry professor Harold Fales and announced at the NL summer meetings in mid-July 1925.) Besides, as Bill Curran notes in Big Sticks (William Morrow, 1990), if the owners had wanted to enliven the ball, they would have had no reason to hide this change. Why risk a conspiracy when the public’s faith in the game was already shaken by the Black Sox Scandal?

Baseball researcher Bob Schaefer recently uncovered a fascinating interview with George Reach of A. J. Reach and Company, manufacturer of AL baseballs (Baseball Digest, July 1949). He admits that his company did tinker with the liveliness of the ball from time to time. He credits the tighter tension of the wool yarn more than the makeup of the ball’s core (rubber vs. cork) with the changes. He suggests that the Lively Ball Era could have been helped along by his company’s shifting standards. Yet in September 1921, this very same George Reach was quoted in Baseball Magazine:

We try to manufacture the best baseball that money can buy. There has been no change whatever in our methods of manufacture since 1910. … We have never been requested by the league officials to make any change whatever nor have we made any changes of our own volition [other than the introduction of the cork-centered ball in 1910-11].

This article went on to say that Reach’s words must be accepted “on faith” because of the reputation of “a man whose word would not be lightly questioned by anyone who has ever seen him.”

There was also a lengthy article in The Sporting News (March 12, 1936) by columnist and cartoonist Edgar F. Wolfe (under his pseudonym of Jim Nasium), written shortly after the death of Tom Shibe. Shibe was the President of the Philadelphia Athletics and part owner of the Reach Company. He had insisted that the ball had not been changed in the late teens or 1920s, “barring improvements in the method of manufacture.”

It is possible to reconcile the denials of the owners, even those of ball manufacturers like Tom Shibe, with the fact that the ball may indeed have become livelier. It is time to consider this as one of the factors that affected play, without making it the key factor. Ball manufacturers were always trying to make a better and longer-lasting ball. (This was the impetus for the introduction of the cork-centered ball in 1910.) The use of better raw material — namely, Australian wool — after World War I deserves more attention than it has received. (It may have contributed to the rise of offense in 1919.) AL President Ban Johnson wrote to Baseball Magazine in September 1921:

It [Australian wool] permits of a firmer winding, a harder ball, and naturally one that is more elastic.

This higher grade of yarn, which had more spring and could be wound tighter, coupled with mechanical improvements in the winding and sewing machines, did result in some change.

The funny thing about it was that Tom Shibe, working only to improve the quality of the ball and make it more durable, never realized the effect that this would have on the playing of the game.

— Jim Nasium, The Sporting News, March 12, 1936

The Sporting News technically could state “the 1914 and the 1925 ball are twins, so far as their component parts are concerned” (editorial, July 23, 1925). It moved to shakier ground when it wrote (in the same editorial) that “not one iota, molecule or microbe of difference exists today in the manufacture and material of the ball from the original contract.”

Even the Fales study noted that the seams of the 1920s ball seemed to be more countersunk and flush with the leather than the ball of the Deadball Era. The almost seamless ball (better sewing machines?) would have been harder to grip, with less “break” than its predecessor, thus making it easier to hit.

It is also possible to reconcile the explosion of hitting that started in 1920 with changes in the liveliness of the ball that may have occurred earlier (per Mr. Reach). Until Babe Ruth came along and showed the way, hitters did not try or know how to take advantage of a livelier ball, if there was one.

Perhaps the era was ushered in more by “lively bats” than by lively balls. Babe Ruth revolutionized the game by swinging for the fences from the end of the bat. Managers began designing their offense around the big blast, rather than “small ball.” The “Inside Game” of bunt, steal, and sacrifice was quickly disappearing. This new hitting style meant that balls went farther and hit the gaps quicker than before.

A number of issues remain to be explored: Are the test studies, like that of Professor Fales, still available for review? After all, he concluded that the 1920s balls did not change in elasticity from those of the Deadball Era. It also should be noted note that strikeouts per game dropped significantly in the 1920s. This seems counter intuitive, with hitters free-swinging from the end of the bat. Perhaps the elimination of trick pitches may have set this off.

The tragic death of Cleveland’s Ray Chapman, hit by a pitch thrown by Yankee submarine pitcher Carl Mays, resulted in a change that benefited hitters tremendously. Until that time the same ball stayed in play for long periods of time, even after it became grimy and dirty and thus a poor target for a hitter to see. Chapman might have had a difficult time picking up the darkened ball. Henceforth, the umpires were instructed to replace scuffed and soiled balls.

Mike Sowell, in his classic book The Pitch That Killed, notes that umpires were directed to introduce clean balls at the start of the 1920 season. But owners complained of needless increased costs, and the umpires backed off somewhat, at least until the Chapman tragedy. Not surprisingly, the lowest earned-run averages of the Lively Ball Era came in its first year. This could also be explained by the early stages of the new hitting styles and the relearning of the curve ball.

| NL | AL | |

|---|---|---|

| 1920 ERA | 3.13 | 3.79 |

| 2nd Lowest ERA (1920-39) |

3.34 (’33) | 3.98 (’23) |

| 3rd Lowest ERA (1920-39) |

3.78 (’21, ’38) | 4.02 (’26) |

Hitters now had a bright white ball to target throughout the game. The change was huge. There were 43,224 balls used in the National League in 1924, a dramatic increase from a total of 14,772 used in 1916 (Baseball Magazine, September 1925). Even more impressive is that 32,400 more balls were used in 1925 than in 1915 (New York Sun, January 4, 1926).

Finally, the introduction of better hitting backgrounds in many ballparks gave the hitter an even clearer view of the ball. Taken together, these changes had a profound impact on improving hitting, both for average and for power.

The fans loved the new style of play. Attendance climbed dramatically, clearly driven by more than the end of the war. The 1920s saw an average of well over 9 million fans a year, as compared to less than 6 million in the teens (Total Baseball).

There is very positive evidence in the jammed ball-yards that the multitude finds the cruder, more robust, freer walloping game of the present more attractive. And in baseball, more perhaps than any other sphere, the majority rules.

— Baseball Magazine, July 1923

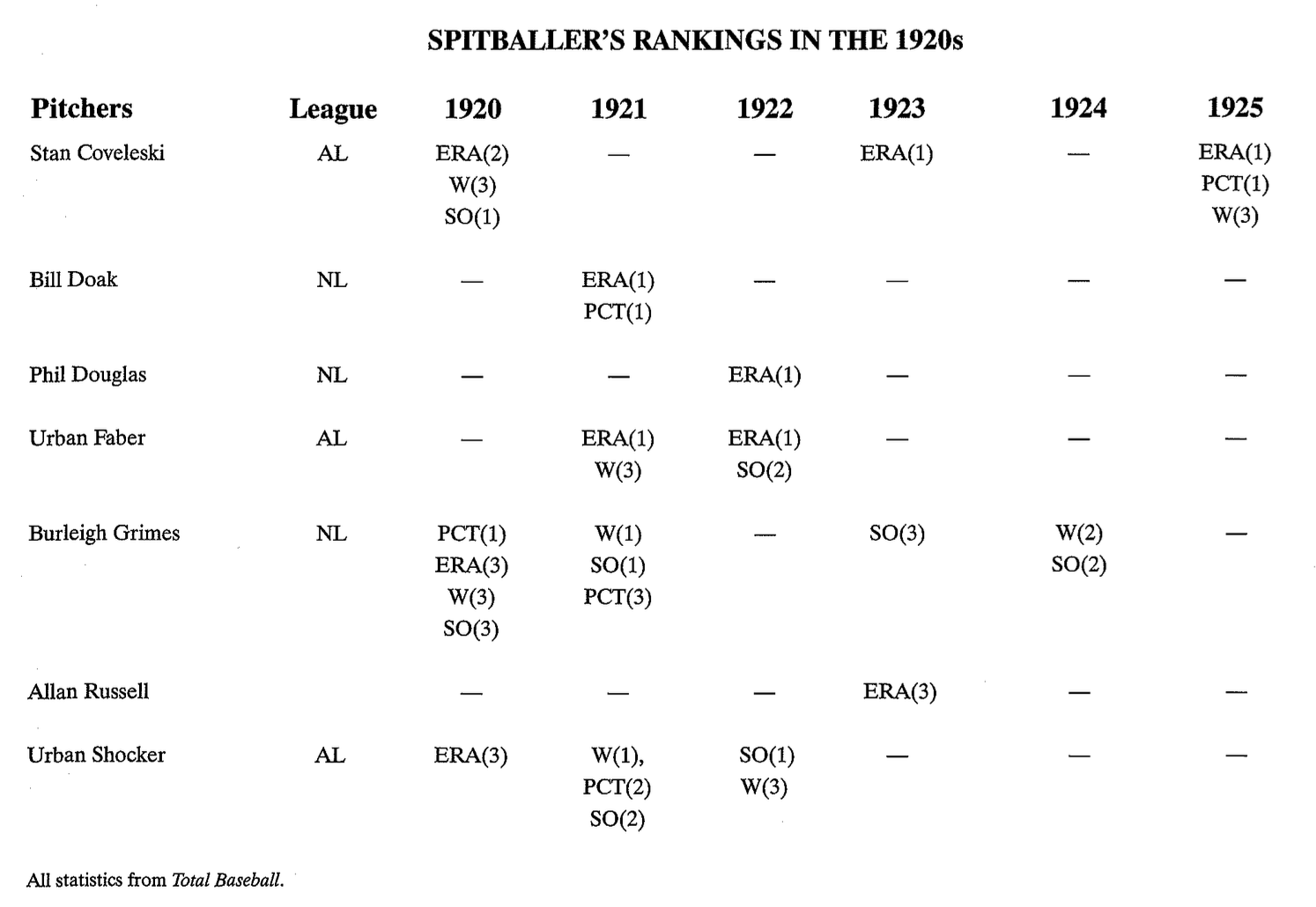

New York Giants pitcher Hugh McQuillan might have complained that the lively ball was making “bums out of pitchers” (New York Herald Tribune, June 21, 1925), but talented pitchers with great control like Grover Cleveland Alexander and Walter Johnson continued to excel. And the dearth of great spitballers had ended. In the 1920s, a number of great and near-great spitballers dominated the game: Coveleski, Faber, Grimes, Quinn, and Shocker.

Once the spitter was banned, there was no more discussion of its danger to the arms of the protected hurlers. No wonder. The dominant spitball pitchers had incredibly long and productive careers. Coveleski pitched until he was 39 years old; Faber until he was 45; Grimes until he was 41; and Methuselah Jack Quinn until he was 49. Urban Shocker pitched until he was 37 and was stopped only by heart disease that claimed his life less than a year after he went 18-6 for the 1927 Yankees.

It’s because I’m a spitball pitcher that I am able to keep on going. The spitter is the easiest delivery there is upon the arm. If it were not so, how do you account for the success of Jack Quinn . . . Ed Walsh did not have to quit because of the spitter. It was overwork that turned the trick.

— Red Faber, New York World, December 15, 1929

Table 2: Spitballer Rankings in the 1920s

(Click image to enlarge)

ADDENDUM

Ironically, the very baseball establishment that banned the spitter later voted five of its fraternity into the Hall of Fame: Chesbro and Walsh (elected by the Hall’s Old Timers’ Committee in 1946), and Coveleski, Faber, and Grimes (later elected by the Hall’s Veterans’ Committee). None won 300 games, and Chesbro and Walsh won less than 200 games. While they continued to be about 10% more effective than pitchers as a whole, all pitchers gave up about one more full run a game than they had before 1920.

A number of factors shut down the Deadball Era: the ban on “freaks” other than the spitter, no new spitballers, the new hitting style and improved hitting backgrounds, as well as the constant flow of fresh, bright, and better quality balls. Taken together, they provided the impetus for a stunning and sudden change, one of the biggest in baseball history.

(In the 1950s and 1960s, there was a movement to legalize the spitter. Not only former hurlers Ed Walsh, Red Faber, and Burleigh Grimes supported the move; so did executive Branch Rickey and the Commissioner of Baseball, Ford Frick. Even Billy Evans, now a baseball executive, endorsed the move. The movement was not successful.)

“Bring back the spitball.”It may be the wrong answer, it may be a romantic answer, but many old-timers share that dream. To them the spitball era does, truly and clearly, represent romance. It represents the time when the pitcher was king.

— John L. Lardner, “Will They Bring Back the Spitter?” Saturday Evening Post, June 17, 1950

The rule changes that major league baseball instituted in February 1920 included two that affected the ball and pitching. Rule 14, Section 4, “Discolored or Damaged Balls,” had previously read:

In the event of a ball being intentionally discolored by rubbing it with the soil or otherwise by any player, or otherwise damaged by any player, the umpire shall forthwith demand the return of that ball and substitute for it another legal ball as hereinbefore described, and impose a fine of $5.00 on the offending player.

— 1918 Reach Official Guide

The new Rule 14 (“The Ball”), Section 4 was more expansive and punitive:

In the event of the ball being intentionally discolored by any player, either by rubbing it with the soil, or by applying rosin, paraffin, licorice, or any other foreign substance to it, or otherwise intentionally damaging or roughening the same with sand or emery paper or other substance, the umpire shall forthwith demand the return of that the ball, and substitute for it another legal ball, and the offending player shall be disbarred from further participation in the game. If, however, the umpire cannot detect the violator of this rule, and the ball is delivered to the bat by the pitcher, then the latter shall be at once removed from the game, and as an additional penalty shall be automatically suspended for a period of ten days.

— 1920 Reach Official Guide

Rule 30 (“The Pitching Rules”) had previously discussed only “The Delivery of the Ball to the Bat.” It now had a new Section 2 which stated:

At no time during the progress of the game shall the pitcher be allowed to (1) apply a foreign substance of any kind to the ball; (2) expectorate either on the ball or his glove; (3) to rub the ball on his glove, person, or clothing; (4) to deface the ball in any manner, or to deliver what is called the “shine” ball, “spit” ball, “mud” ball, or “emery” ball. For violation of any part of this rule the umpire shall at once order the pitcher from the game, and in addition he shall be automatically suspended for a period of ten days, on notice from the President of the league.

Note: In adopting the foregoing rules against freak deliveries, it is understood and agreed that all bonafide spit ball pitchers shall be certified to their respective Presidents of the American and National League at least ten days prior to April 14th next, and that the pitchers so certified shall be exempt from the operation of the rule, so far as it relates to the spit ball only, during the playing season of 1920.

The language was the same in the Reach and Spalding Guides.

STEVE L. STEINBERG has recently completed a book on Miller Huggins, The Genius of Hug. He is finishing a book on spitball pitcher Urban Shocker, Shocker! Discovering a Silent Hero of Baseball’s Golden Age. He lives in Seattle with his wife and three children.