SABR BioProject: October 2018 Newsletter

High and Inside

The Newsletter of the BioProject Committee

Society for American Baseball Research (SABR)

October 2018

Editor: Andrea Long

From Co-Director, Rory Costello

Disappearing Images

Perhaps you’ve noticed that the pictures accompanying certain biographies have either disappeared or that there’s a blank space where the image should be. What gives?

When SABR’s hosting company upgraded its server last summer, a technical issue arose with some older images (mostly ones that were uploaded before 2008). Details are available on request if you’re really interested.

It’s a pesky problem, but it only affects a handful of bios and photos, and, in nearly all cases, it’s a simple spot fix. If you see any photos like that, just let Rory Costello or Jacob Pomrenke know.

Negro Leaguers

The BioProject has more than 100 biographies of Negro Leaguers. This effort has been bolstered by book projects, including 2017’s Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series. Yet more bios remain welcome.

Also, you may help in another small way. Many Negro Leaguers still do not have nodes on the BioProject — i.e., URL addresses that enable the name to show up in searches. For example, we recently added two top-rank Negro League pitchers: Chet Brewer and Cannonball Dick Redding. If you notice that any other players do not have a node, alert Lyle Spatz, and he will create one.

The chairman of the Negro Leagues Research Committee is still Larry Lester.

“Biographies” of fictional players

The BioProject has published a couple of “biographies” of fictional characters, such as Joe Hardy, from the musical comedy Damn Yankees, and the Peanuts cartoon character Charlie Brown — they are posted in the Topics section of the website.

Though the precedent has been established, we’d like to remind authors that this is not a subgenre we wish to pursue actively.

From the Editor

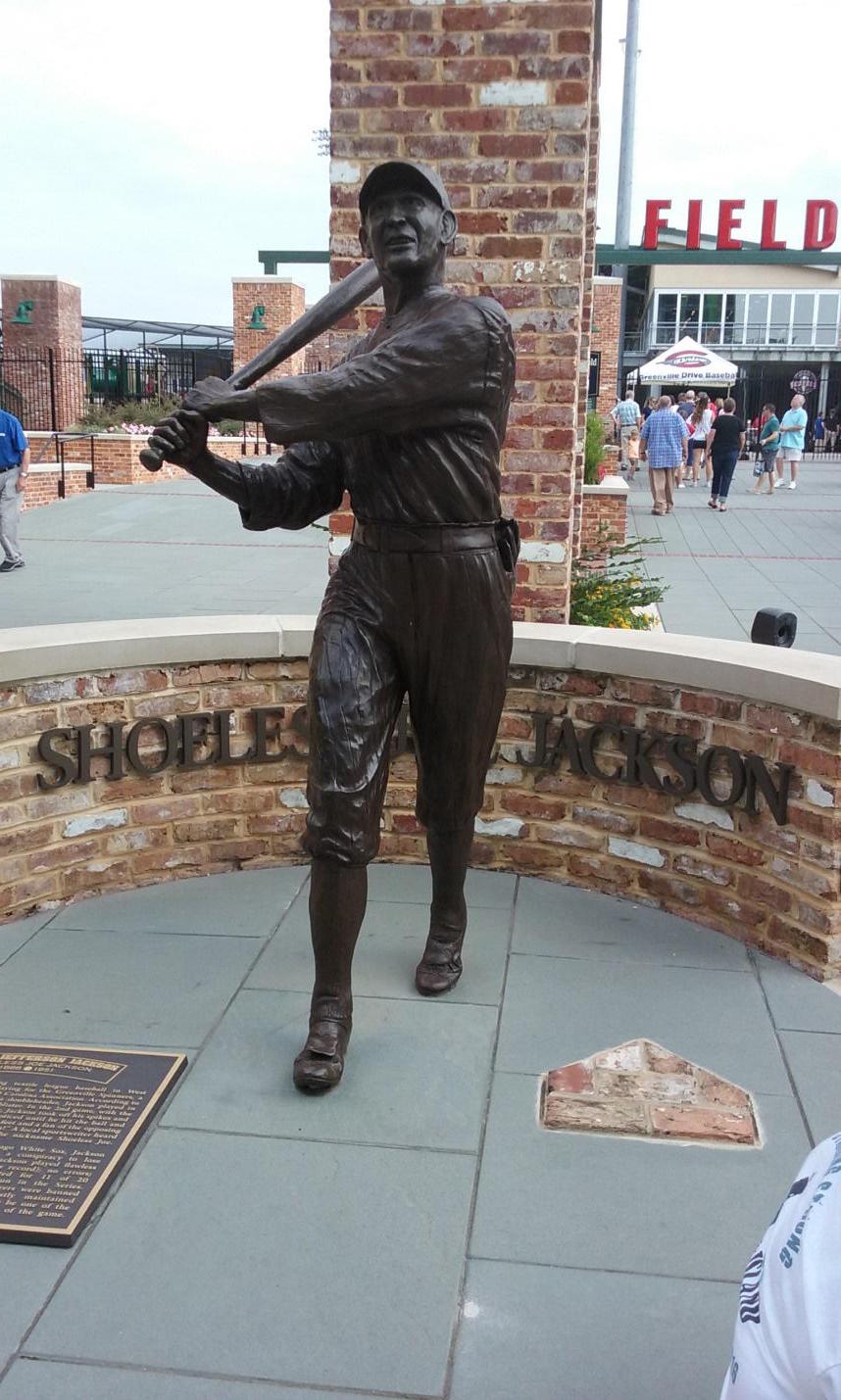

God knows I gave my best in baseball at all times and no man on earth can truthfully judge me otherwise. — Shoeless Joe Jackson

Sometimes, an opportunity you never realized you wanted falls into your lap.

Every year, my hometown Charlotte Knights sponsor a bus trip for season ticket holders (or, as I call us, The Island of Misfit Toys) to see the Knights play on the road or to see another nearby team. This summer’s trip was to watch the Greenville Drive play the Lexington Legends at beautiful Fluor Field in Greenville, SC. Fluor Field, with its manual scoreboard and its own Green Monster, happens to be located directly across the street from the Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum.

I’d had only a passing interest in Shoeless Joe (Field of Dreams and all), but I got very interested very quickly when I knew I was going to be in the house he lived in for the last ten years of his life until his death there of a heart attack in 1951.

It’s an interesting experience. You’re in an average-looking house, entirely of its era, with normal household objects around. It is unremarkable until the feeling fully settles over you that you are standing in not just any house, but Shoeless Joe Jackson’s house. And then, I think regardless of your opinion of him, it seems like hallowed ground.

How the house came to be across the street from the ballpark is a story of dedication, tenacity, and community involvement. The house’s original location was at 119 E. Wilburn Avenue, about three miles from where it sits now at 356 Field Street — 356 representing Jackson’s lifetime batting average.

In 2005, Richard Davis (formerly of A&E’s Flip This House) approached Arlene Marcley, then the assistant to Greenville’s mayor, about the Jackson house. Marcley had been doing exhibits on Jackson in the city hall lobby and had become the local authority on Shoeless Joe. Davis told her he was going to buy the house (vacant for years and in disrepair), move it, and film the experience for his new TLC show, The Real Deal. After the show aired, he would deed the house to a non-profit foundation. Marcley’s job was to find a new location for the house and to create the non-profit.

As fate and perfect timing would have it, a new downtown minor league ballpark was nearing completion. The owner of a parking lot across the street donated a portion of his land for the Jackson house, and in April 2006 the house was cut in half, placed on two large trucks, and moved to its new location. The program aired in 2007, the house was deeded to the foundation, and the museum opened in June 2008.

Louisville Slugger bat made to Jackson’s playing specifications. This model has not been produced since his playing days. This bat is 36 inches long and weighs approximately 39 ounces. (His bats were 36 inches long and weighed 38.75 ounces.) You’ll be overwhelmed by the desire to pick it up, and you’re allowed to. It’s as solid as it looks. It’s like holding a club.

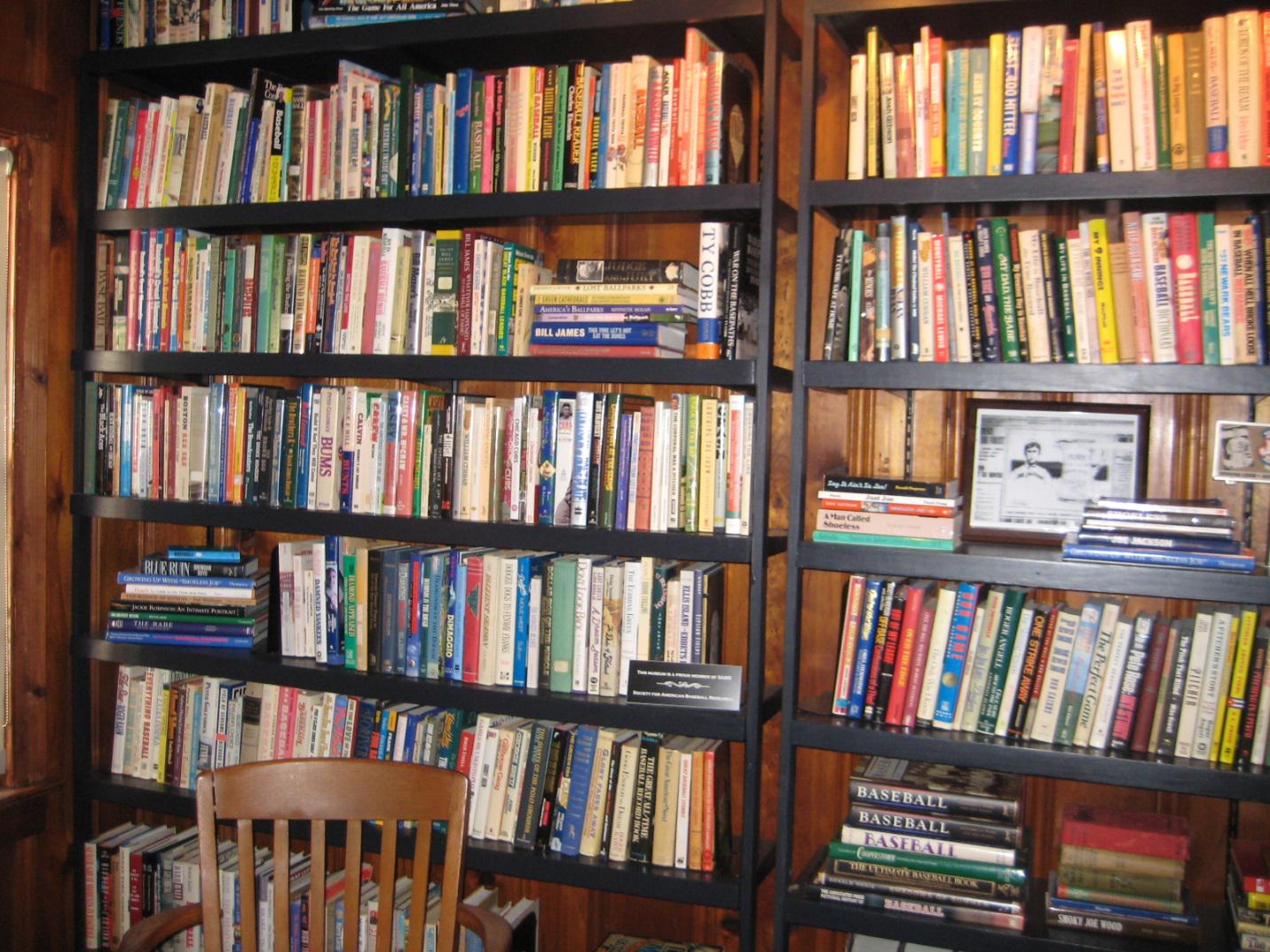

One of three full walls of the museum’s impressive library of baseball books. Many of the books were donated by the late Gene Carney, author and SABR member, who put out the word to other members that the museum wanted baseball books. In the end, over 2,000 books were donated, most of them by SABR members.

Lower left: original stadium seat and bricks from Old Comiskey Park

At the main gate of Fluor Field

For a very detailed account of the move and restoration of the house, I recommend ordering Baseball History & Art magazine from the museum’s gift shop. It’s a beautiful edition that contains an in-depth interview with Arlene Marcley. This interview was helpful in refreshing my memory on the details of the move and also gives a true picture of the yeoman’s work Marcley did to bring the house to its current condition. She was and remains the driving force behind the museum.

Greenville is a fun, dynamic city with great restaurants and shopping, a thriving cultural scene, and, of course, minor league baseball. If you’re in the area, it makes for a wonderful day trip or weekend stay, especially during baseball season. The museum is a treasure, lovingly curated, cared for, and run entirely by volunteers. It has limited operating hours, but tours are also available by appointment. You’ll find the staff to be friendly, welcoming, and ready to answer your questions. They’re also happy for you to take your time exploring the house on your own. Months later, it’s an experience that has stayed with me. I look forward to visiting again someday.

For more on Shoeless Joe and the 1919 World Series, check out the excellent newsletter of SABR’s Black Sox Scandal Research Committee, headed up by Jacob Pomrenke.

As always, your comments, ideas, contributions, and suggestions for this newsletter are most welcome. Keep those cards and letters coming, folks!

With this, we wrap up until 2019. Happy Thanksgiving, Happy Hanukkah, Happy Festivus (hat tip to my predecessor, Stew Thornley), Merry Christmas, Happy Kwanzaa, and Happy New Year, too!

— Andrea Long

Follow the BioProject on Facebook.

Follow the BioProject on Twitter.

In closing, here are some really nice numbers:

Update on BioProject Submissions

The total number of biographies in the BioProject now stands at 4,656. Since the last newsletter, we’ve added 126 bios, including five by first-time authors.

Rory Costello (Co-Director, Chief Editor)

Gregory H. Wolf (Co-Director)

Mark Armour (Director, Emeritus)

Jan Finkel (Senior Editor, Emeritus)

Len Levin (Senior Editor)

Warren Corbett (Chief Fact Checker)

Bill Nowlin (Team Projects)

Lyle Spatz (Assignments)

Emily Hawks (Modern Initiative – 1980s/1990s)

Scott Ferkovich (Ballparks Project)