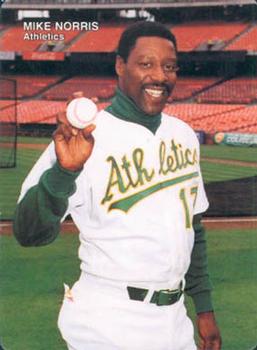

April 11, 1990: Mike Norris makes a comeback against all odds

Baseball takes on an extended mythology when accompanied by a subplot of conflict, whether national, local, or personal. The game parallels our image of the human experience, of the randomness of life no matter how much we try to control or improve it. Perhaps this is due to its democratic nature, each player getting a similar number of chances to contribute, tilting the odds so fluidly in an underdog’s favor. It could be its sense of timelessness or that it is a summer game, both of which remind us of how precious both free time and summer are. It is also played by mostly quite imperfect people of common stature, giving us a keener sense of their personalities, triumphs, and failures.

Baseball takes on an extended mythology when accompanied by a subplot of conflict, whether national, local, or personal. The game parallels our image of the human experience, of the randomness of life no matter how much we try to control or improve it. Perhaps this is due to its democratic nature, each player getting a similar number of chances to contribute, tilting the odds so fluidly in an underdog’s favor. It could be its sense of timelessness or that it is a summer game, both of which remind us of how precious both free time and summer are. It is also played by mostly quite imperfect people of common stature, giving us a keener sense of their personalities, triumphs, and failures.

All of these elements were at work in early April of 1990 when the hometown Oakland Athletics took on the Minnesota Twins in what would have been a relatively uneventful affair apart from the highly unlikely reappearance of Bay Area native son and one-time A’s star pitcher Mike Norris after over six years removed from the major leagues.

Michael Kelvin Norris began his career as the picture of a local kid made good, drafted by the A’s in the first round out of City College of San Francisco, eight miles across San Francisco Bay, in 1973. He quickly made his way through stints at Class A (Burlington, Iowa) and Double A (Birmingham, Alabama), and while Mike dominated that competition, he encountered deep racism in his travels across the rural Midwest and Deep South over the next two seasons. In a 2015 interview, Norris said, “When I signed that contract, I was taught that I had to be twice as good as any of those white guys, or I wasn’t going to make it. I digested that, but didn’t keep it in the front of my mind — that wasn’t good motivation. Had it not been for my roommates Claudell Washington and Derek Bryant, I don’t know if I would’ve survived.”1

Norris did survive, though, and earned a spot with the A’s in 1975, shutting out the Chicago White Sox in his debut while facing just 32 batters. He saw limited action that year but joined the starting rotation permanently in ’76. He was often injured and struggled during his initial four seasons as the team underwent annual overhaul of its coaching staff. When the Walter Haas family succeeded Charlie Finley as the team’s new owners in 1980, they changed course dramatically by coaxing Berkeley, California, native and World Series-winning manager Billy Martin to the helm. This proved to be a boon for the franchise and ushered in a magical season for Norris.

Relying heavily on a deceptive screwball, Norris surged to a 22-9 record in 1980, along with a 2.53 ERA and 1.048 WHIP, while winning a Gold Glove and leading the league with just 6.8 hits allowed per nine innings. He pitched nine complete games in which he allowed four or fewer hits.2 The 22 wins tied Norris with Tommy John for second-most in the AL, topped only by Cy Young Award winner Steve Stone, and had Mike in the middle of a promising young pitching rotation that also included Rick Langford, Steve McCatty, and Matt Keough. The next season, 1981, he won another Gold Glove and was named to his only All-Star Game in a strike-shortened season. At that point, Norris’s heavy workload over almost a decade was showing noticeable physical impact, and he admittedly did not stay in optimum playing shape during the layoff. He required offseason surgery to repair nerve damage in his shoulder, and the prolonged hiatus proved to be his downfall, not solely because of the injury but also due to an accompanying battle he had been waging for years that finally got the best of him.

Norris had come of age during a time when a significant number of professional athletes were using cocaine recreationally, and he was no exception. By the time he was rehabbing from surgery, he was heavily involved with the drug and was arrested twice. He had seemingly fallen out of baseball apart from brief minor-league stints, in between which he was in a downward spiral leading up to New Year’s Day 1986. After consuming $300 worth of cocaine the night before, Norris decided that morning that he was finished with drug abuse. He insists he has never relapsed.3 While most of his circle of influence had abandoned him at that point, he met a Bay Area-based flight attendant named Lenise Patrick in the spring of ’86, and as of 2020 the two have been together ever since. He credits her as his primary influences in fully recovering from his addiction. Norris told Ross Newhan, “There are three things you can look forward to with cocaine: hospitalization, incarceration, and death. I’d done two of the three. The only thing left was death. It was the next step. The only way out of the misery. The madness.”4

Norris made a final comeback attempt in 1989 with the A’s Triple-A Tacoma farm team. His 6-6 record and 3.18 ERA earned him a relief role on Oakland’s 40-man roster in 1990 as a 35-year-old, but he needed his manager’s confidence to make the final Opening Day roster. “The need for pitching is so important, so Norris will be there,” said A’s manager Tony La Russa. “He has a lot of composure, plus a lot of different pitches. He’ll help us. He won’t be affected by numbers as long as he plays.”5 The miracle was within reach.

On April 11, 1990, 15 years and a day from shutting out the White Sox in his debut, Norris found himself on the mound back in Oakland to start the eighth inning in front of 27,775 admiring and surely curious fans, on the cusp of deliverance from what he called “the closest thing to the devil on earth.”6 He dealt effortlessly, setting the side down in order on 14 pitches. He started again with ease in the ninth, getting Kirby Puckett to ground weakly to third and Kent Hrbek to pop to short center before allowing a single and walk. La Russa had a reputation for holding short leashes on his pitchers, but stuck with Norris for one last batter, Greg Gagne. Gagne drove a ball hard to the left-center-field gap, but Dave Henderson clasped it to close the historic two-inning shutout relief appearance. Just like old times, only better.

While Norris was released by the A’s later in 1990, he had gained an inestimable second lease on life. He leveraged his experiences to help underprivileged youth in the Bay Area flourish in life. “I really love helping these kids,” Norris told the Richmond (California) Standard in 2020. “I grew up in the projects in the Western Addition. I know what poverty is, what poor is, and I wasn’t even in as bad a situation as some who grew up in my neighborhood. I had clothes and a baseball glove.”7 On the Board of Directors for the San Pablo Baseball Association, he sought to implement such initiatives as finance literacy and STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) classes as part of the Mike Norris Baseball Academy, a league he started to help almost a dozen underserved local communities and anchored by a local Boys and Girls Club chapter.

In the spring of 2007, Norris returned to the Coliseum to be honored as one of the 13 “Black Aces” of baseball, a nod to the 13 African-American pitchers who have won 20 games in a major-league season. Norris and three of the others — Dave Stewart, Vida Blue, and Mudcat Grant– all hurled for the A’s. He suffers from a compressed spinal cord condition called cervical myelopathy, which has partially paralyzed his legs. At the Coliseum he referred to the inspiration given him by his then 9-year daughter. “It’s not what keeps me clean, but that’s what keeps me going. She’s been able to put another 10 years on my life,” he told the San Jose Mercury News. “What I took off in the midst of my drug intake, she’s given back.”8

Norris’s life had become an astounding saga of collapse and resurgence.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Owen Watson, “Mike Norris and the Moral Winter,” The Hardball Times, March 5, 2015, tht.fangraphs.com/mike-norris-and-the-moral-winter/.

2 Ross Newhan, “Norris’ Road Back Full of Self Discovery,” Washington Post, April 18, 1990. washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1990/04/18/norriss-road-back-full-of-self-discovery/b8529fad-44e2-4889-9d9d-8b9113d13b69/.

3 Newhan.

4 Newhan.

5 “Oakland’s Mike Norris Gets an ‘A’ From Fans for Comeback Effort,” Los Angeles Times, April 12, 1900. latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-04-12-sp-1802-story.html.

6 Newhan.

7 “Former Oakland A’s Great Mike Norris Joins San Pablo Baseball Association,” Richmond Standard, January 28, 2020. richmondstandard.com/beyond-richmond/2020/01/28/former-oakland-as-great-mike-norris-joins-san-pablo-baseball-association/.

8 Daniel Brown, “Black Aces: A’s Mike Norris Battling Back,” San Jose Mercury-News, May 31, 2007. mercurynews.com/2007/05/31/black-aces-as-mike-norris-battling-back/.

Additional Stats

Minnesota Twins 3

Oakland A’s 0

Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum

Oakland, CA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.