April 30, 1951: New York Giants start long climb out of the cellar

Nothing in the early spring of 1951 gave any clue that this would be the New York Giants’ season of miracles. The year when the Giants overtook the Dodgers in baseball’s most dramatic pennant race saw the New Yorkers drop 12 of their first 14 games, and by the end of April they were in undisputed possession of last place.

Nothing in the early spring of 1951 gave any clue that this would be the New York Giants’ season of miracles. The year when the Giants overtook the Dodgers in baseball’s most dramatic pennant race saw the New Yorkers drop 12 of their first 14 games, and by the end of April they were in undisputed possession of last place.

As the disastrous month of April moved to its close, the Giants faced the Dodgers in enemy territory: the claustrophobic confines of Ebbets Field. The Giants dreaded playing on the Dodgers’ home ground. Brooklyn fans, notorious for raucous noise and nasty behavior toward all opposing teams, saved their worst vitriol for the Giants. Leo Durocher recalled how Dodger fans spat at him, threw things at him, sprayed him with Coca-Cola, and called him “every filthy name they could think of.”1 Monte Irvin declared that “it was an experience just going in and getting out alive.”2 Bobby Thomson remembered Durocher feeding his players a repetitious diet of hatred against the Dodgers, casting the Brooklynites not merely as rivals but as horrible human beings, creating an enmity that continued off the field. According to Thomson, Durocher claimed the Dodgers were “the kind of guys who, if you take your eyes off them at a party, they started groping your wife’s tits.” Listening to such talk day after day, Giants players learned to despise the Dodgers. “We didn’t even talk to those fellows,” Thomson recalled, and he compared playing at Ebbets Field to “walking into a lion’s den.”3

After they got trounced by the Dodgers two days in a row (April 28 and 29), the reeling Giants’ record was 2-12. The last-place New Yorkers had suffered 11 straight defeats, and the jubilant Dodgers rushed to rub their noses in the dirt of the cellar floor. After Brooklyn’s victory on April 29, some of the Dodgers gathered in front of the door to the Giants’ locker room and taunted their vanquished opponents, hurling easily audible insults. Monte Irvin remembered hearing the voices of Carl Furillo and Jackie Robinson shouting, “Eat your heart out, Leo, you sonofabitch. You’ll never win it this year!”4 The addition of insults to the injury of defeat was too much for Durocher, who exploded at his team with language that shocked even the veterans of his tirades. According to Bill Rigney, Durocher “was so hot you could have fried eggs on the language coming out of his mouth … motherfucking this, cocksucking that.”5 After ten minutes or so of Leo’s scorching insults, an interruption by the batboy with an innocent question caused Durocher to pick up one of the players’ gloves and hurl it at the wall. But then a couple of well-timed comments by Alvin Dark and Eddie Stanky broke the tension, and suddenly everybody, including Durocher, was roaring with laughter. “[The Dodgers] must have been able to hear [Leo],” Rigney continued. “Now they hear this hysterical laughter. They must have thought we were all gone crazy, like maybe we murdered Leo and were all celebrating over his body.”6

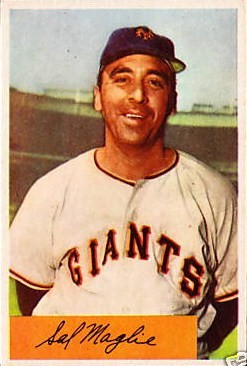

Durocher’s tirade and its funny ending had a positive effect: It broke the spell of defeatism. The next evening, April 30, the Giants defeated the Dodgers before an unhappy throng at Ebbets Field.7 Although he did not complete the game, the starter and winner of the contest that began the Giants’ climb out of the cellar was Sal Maglie. His teammates gave Sal a comfortable cushion by pouncing on three Dodger pitchers for six runs in the top of the first. Brooklyn counterattacked in its half of the inning as Gene Hermanski led off with a home run. Maglie’s first pitch to the next batter, Carl Furillo, came closer to giving him a haircut than one of the pitcher’s famous close shaves. The shaken Furillo flied out, but the Dodgers then scored another run on a homer by Jackie Robinson. The Giants put up two more runs in the second, and the Dodgers chipped away at Maglie for a run in their half of the inning, when Sal the Barber’s intimidation tactics failed to work against Pee Wee Reese. After Sal knocked him down, Reese bounced to his feet, socked a double, and scored on a single by Rocky Bridges. In the top of the third, the fourth Dodger pitcher of the evening, Clem Labine, engaged in some payback by decking Bobby Thomson.

But the real nastiness began with Robinson’s second at-bat, in the bottom of the third. Jackie had hit a home run his first time up, and this time on his first pitch Sal shaved Jackie’s chin with a fastball. On Maglie’s next pitch, a slow changeup, Robinson pulled a perfect ploy: He dropped a bunt down the first-base line. But then, instead of sprinting to first, he held back a little, gauging the distance and timing himself, watching Maglie as the pitcher charged off the mound to field the bunt. As Sal bent over near the foul line, his attention on the ball (which was rolling foul) rather than on Robinson, the 210-pound former football star gathered speed and barreled into Maglie. The force of the collision sent Sal sprawling in the dirt. Cursing a blue streak, the pitcher scrambled to his feet and lunged at Robinson – the closest Maglie ever came to an on-field fight. Members of both teams intervened to keep the two men apart. Durocher hurried out to calm his furious pitcher, and plate umpire Babe Pinelli said a few soothing words to the bristling Robinson. The game resumed, and Jackie tagged Sal for a single, but the pitcher struck out Gil Hodges to end the inning. The Giants scored no further runs, and although the Dodgers picked up two more, the rest of the game was uneventful. The Giants won it 8-5.

The third-inning collision between Maglie and Robinson became one of baseball’s fish stories, with the confrontation growing bigger in later retellings. Most newspaper accounts of the game, published the next day, took note of the clash, but none devoted much space to it.8 One later account contains numerous inaccuracies, including the claim that Robinson “made it to first,” when in reality the ball rolled foul and he returned to the plate. Another asserted that Jackie “barged into Maglie with crushing force,” and that Maglie and Robinson “had to be pried apart” by their teammates, although firsthand accounts indicate that the two men never tangled.9 Sportswriter Joe Overfield claimed that Robinson “body-blocked Maglie almost into right field,” and Maglie biographer James Szalontai wrote that Robinson sent Sal “flying into the air,” both far-fetched descriptions unsupported by newspaper descriptions.10 As a fish story teller, David Falkner topped them all by asserting that “Robinson left [Maglie] printed in the earth like a cartoon Road Runner.”11

The flare-up had one immediate consequence: Ford Frick, president of the National League and soon to replace Happy Chandler as the new baseball commissioner, took Maglie’s side against Robinson. Frick maintained he had received no reports from umpires of pitchers dusting off batters and snapped: “I’m getting tired of Robinson’s popping off. I have warned the Brooklyn club that if they won’t control Robinson, I will.”12 Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley, who disliked Robinson but disliked even more seeing one of his players criticized by the league’s top official, insisted that Jackie had the full support of the Dodger organization. Robinson also fired back, declaring, “Let Mr. Frick change the color of his skin … and go out there and hit against Maglie.”13 Although Robinson’s implied charge of racism must have hurt Maglie, who was the least prejudiced of men, the pitcher refused to be drawn into this war of words. He knew that racism had nothing to do with his conduct toward Robinson. The only colors he paid attention to were the colors on a batter’s uniform. Maglie was an equal-opportunity intimidator.

This article appeared in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III.

Sources

This essay is based on material from Judith Testa, Sal Maglie, Baseball’s Demon Barber (Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2007).

Notes

1 Leo Durocher and Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1975), 234.

2 Monte Irvin and James A. Riley, Nice Guys Finish First (New York: Carroll and Graf Publishers, 1996), 141.

3 Roger Kahn, October Men: Reggie Jackson, George Steinbrenner, Billy Martin and the Miraculous Finish in 1978 (New York: Harcourt, 2003), 14; William Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era: 1945-1951 (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1999), 414; Lee Heiman and Bill Gutman, The Giants Win the Pennant! The Giants Win the Pennant! (New York: Kensington Publishing Company, 2001), 94, 95.

4 Thomas Kiernan, Miracle at Coogan’s Bluff (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1975), 66.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Accounts of the game are derived from numerous newspaper stories and from retrosheet.org.

8 Newspapers consulted: New York Times, Daily News, Herald Tribune, and Brooklyn Eagle.

9 Kiernan, Coogan’s Bluff, 67, asserts asserts that Robinson reached base; Ray Robinson, The Home Run Heard ’Round the World. The Dramatic Story of the 1951 Giants-Dodgers Pennant Race (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), 112, claims that Jackie “barged into Maglie with crushing force.”

10 Joseph Overfield, “Giant Among Men,” BisonGram (April-May, 1993): 6; James Szalontai, Close Shave: The Life and Times of Baseball’s Sal Maglie (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002), 130.

11 David Falkner, Great Time Coming: The Life of Jackie Robinson From Baseball to Birmingham (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), 238.

12 New York Times, May 3, 1951.

13 Kiernan, Coogan’s Bluff, 68-69.

Additional Stats

New York Giants 8

Brooklyn Dodgers 5

Ebbets Field

Brooklyn, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.