August 31, 1920: Cubs-Phillies game leads to grand jury investigation, Black Sox confessions, and a stabbing

“Is baseball in danger?” – Chicago Tribune, September 5, 1920.1

The charges of “attempted crookedness” sparked by a game between the Chicago Cubs and the Philadelphia Phillies on August 31, 1920, had repercussions well beyond what anyone could have expected. It was a game that, due to the chain of serious events it precipitated, critics feared might kill the nation’s pastime in the same way gambling had all but “destroyed the sport of horse racing.”2

It turned out the commentators were right to worry. An investigation into this game’s possible corruption uncovered a scandal so great it had the potential to end baseball as a professional sport.

Things began to unravel shortly before game time. A telegram arrived in the office of Cubs President William Veeck: “Commissions of thousands of dollars being bet on Phillies to win today. Rumors that game is fixed. Investigate.”3 More telegrams and phone calls came in, all warning Veeck the game would not be on the level.4

Before its start, the match that day stood as nothing more than the prospect of a relatively unimportant game between two teams that ended the season in fifth (Cubs) and last (Phillies) place in the National League. There appeared to be nothing at stake. So why was so much gambling activity happening with respect to this game?5

Veeck began making inquiries, and what he discovered concerned him. He learned there was “a tremendous amount of money”6 being put on the Phillies, and that the odds of the game had suddenly shifted “from 2 to 1 on the Cubs” to Philadelphia being a “1 to 2 favorite.”7

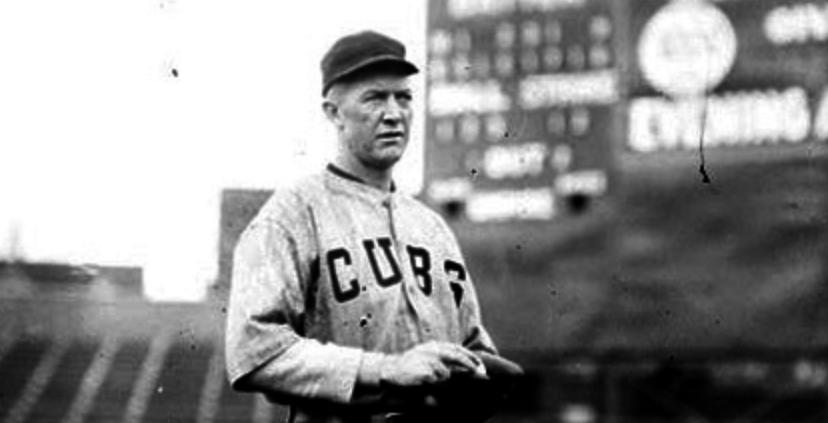

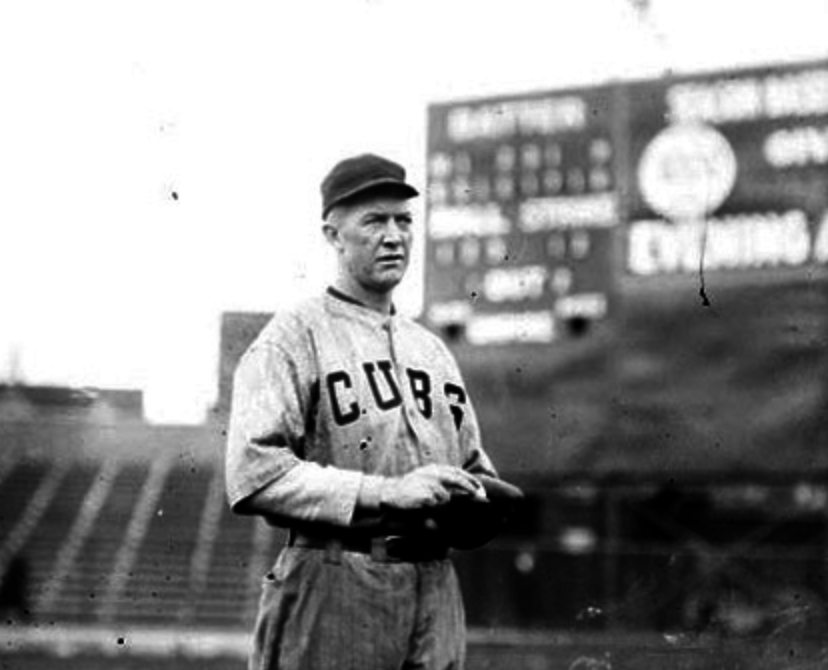

He immediately began to take steps to protect the integrity of the game, switching from the Cubs’ planned pitcher Claude Hendrix to ace Pete Alexander.8 Alexander had already won 22 games in 1920, including his last four decisions. Three days earlier, he had shut out the Brooklyn Robins, who were battling the defending World Series champion Cincinnati Reds for first place in the NL. As an incentive to Alexander, Veeck promised a $500 bonus9 for a victory.

The matchup began with a scoreless first inning, but a controversial error was committed during the second inning. After Phillies shortstop Art Fletcher flied out to right, Bevo LeBourveau hit a sharp single. He was followed to the plate by Ralph Miller, who grounded to second baseman Buck Herzog.10 According to reporting in the Chicago Tribune, Herzog “let the ball get away from him.”11 If Herzog had fielded the ball cleanly – as a grand jury later heard – a double play would have ended the inning.12 Instead, LeBourveau reached third and Miller was safe at first.

The next batter, Mack Wheat, drove “a screaming drive against the brick wall in right center for three bases and both of his mates galloped home.”13 It was the game’s breakout play: Phillies 2, Cubs 0.

After the Cubs fell behind, sportswriters noted that they “had to play an uphill fight and they couldn’t get a start.” In the ninth, after Paul Carter had relieved Alexander, LeBourveau capped his three-hit day by “pol[ing] a homer over the right-field wall, which assured victory” for Philadelphia.14

Philadelphia sportswriters praised Phillies pitcher Lee Meadows for showing “plenty of stuff” and noted that he saw to it that “no one came through with a wallop when a wallop meant danger.”15 Meadows permitted only five hits and four walks. Alexander’s record fell to 22-13 with the loss; he followed this game by winning five of his final six decisions of 1920, giving him the league lead in victories for the sixth time in his career.

The game’s suspicious error, combined with the amount of money being bet on the outcome, and the sudden pregame switching of the odds, led to dramatic subsequent events. On September 4, Veeck hired the Burns Detective Agency to investigate the game’s play and associated betting.

Meanwhile, Judge Charles A. McDonald – a baseball fan and a longtime acquaintance of American League President Ban Johnson and Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey – became involved. After Veeck’s public disclosures about the fact that he was looking into the game’s possible corruption in a statement made to the media in early September,16 McDonald held a private meeting to discuss the matter with Johnson and National League President John Heydler. Things proceeded quickly from there. On September 7, 1920, McDonald brought this game to the attention of a newly empaneled Cook County Grand Jury.17

The grand jury began by looking for indications of possible corruption in this Cubs-Phillies game, but the scope of the inquiry soon widened. By September 10, McDonald had expanded the grand jury’s writ to include consideration of matters beyond the game. “You have been called together to consider baseball gambling in all its ramifications,” he stated.18

This mandate eventually came to include investigation into the 1919 World Series and resulted, on September 28 and 29, in confessions by Joe Jackson, Eddie Cicotte, and Lefty Williams before the grand jury of having colluded with gamblers – an event that rocked the sport, and is still considered one of its greatest scandals.

Just as the nation was being shaken by news of the Black Sox Scandal, the Cubs took part in an exhibition game in Joliet, Illinois, on September 30 against the local Joliet Rivals Club.19 As Herzog was leaving the field, a man yelled out: “You’re one of those crooked Chicago ball players. When are you going to confess?”20 Herzog threw himself at the man and grappled with him. One of the man’s friends lunged forward and slashed at Herzog with a knife, cutting Herzog’s hand and leg.

Herzog later said he was sorry the fight had occurred “but I couldn’t resist punching that fellow when he called me a crook.”21 By that time, Herzog’s baseball career was already suffering. He had previously been suspended by Cubs manager Fred Mitchell, who, according to baseball historian Bill Lamb, “maintained, somewhat improbably, that the move had no connection to the imminent grand jury probe into game-fixing allegations.”22

The Joliet exhibition game in which Herzog was stabbed ended up marking the last time this ballplayer who had helped to precipitate some of the most dramatic events in the history of baseball – and a crisis that nearly killed the sport – would ever wear the uniform of a major-league baseball team.23

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Thomas J. Brown Jr. and copy-edited by Len Levin. My thanks to William (Bill) Lamb, Jacob Pomrenke, and Kevin Trusty for kindly providing feedback on this article during the drafting process.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, information on this game came from Baseball Reference.com and Retrosheet.org, including the box score and play-by-play.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHN/CHN192008310.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1920/B08310CHN1920.htm

Photo credit: Grover Cleveland Alexander with the Chicago Cubs (Chicago History Museum, Chicago Daily News Collection, SDN-064431).

Notes

1 “Start Quiz to Save Baseball from Gamblers: Plot to ‘Fix’ Cub Game Stirs Storm,” Chicago Tribune, September 5, 1920: 1-2.

2 “Start Quiz to Save Baseball from Gamblers”: 1.

3 “Start Quiz to Save Baseball from Gamblers”: 2.

4 “Start Quiz to Save Baseball from Gamblers”: 2.

5 Betting on major-league baseball games was not uncommon in 1920. Media reporting after this game remarked, for example, on syndicates of gamblers operating out of American cities and on the number of lotteries based on ballgames (see “Veeck Shows Vigor in Probing Charges,” The Sporting News, September 9, 1920: 1 and Joe Vila, “Grand Jury Inquiry Scares off Crooks,” The Sporting News, September 16, 1920: 1). What drew attention to the gambling happening with respect to this game related to the significant amounts of money being wagered in several cities. The Charlotte News reported, for example, that gamblers made over $50,000 betting on this game and that bookmakers in Detroit, Cincinnati, Kansas City, and elsewhere had been involved (“Game Was Fixed Is Charge Made,” Charlotte (North Carolina) News, September 5, 1920: 18).

6 Eliot Asinof, Eight Men Out: The Black Sox and the 1919 World Series (Henry Holt and Co. ebook), 149.

7 “Start Quiz to Save Baseball from Gamblers”: 2.

8 Before his start with the Chicago Cubs in the 1918 season, Alexander had had a stellar career with the Phillies (See Jan Finkel, “Pete Alexander,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/pete-alexander/, accessed January 23, 2023).

9 “Start Quiz to Save Baseball from Gamblers”: 1. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics’ “CPI Inflation Calculator” https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm, accessed January 23, 2023, $500 USD in August 1920 would have had the same buying power as over $7,000 in January 2023.

10 “Start Quiz to Save Baseball from Gamblers”: 2.

11 “Start Quiz to Save Baseball from Gamblers”: 2. It is worth noting that Philadelphia reporters covering the game thought Herzog had missed getting the ball because he had been in too much of a hurry. “Alec No Terror to Whaling Phils,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 1, 1920: 14.

12 “Start Quiz to Save Baseball from Gamblers”: 2.

13 “Alec No Terror to Whaling Phils.”

14 “Alec No Terror to Whaling Phils.”

15 “Alec No Terror to Whaling Phils.”

16 The media reported on Veeck’s public statement about his investigation into the game’s possible corruption; see, for example, “Game Was Fixed Is Charge Made.”

17 William F. Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. ebook), 32.

18 From Chicago Daily Journal, September 10, 1920, quoted in Black Sox in the Courtroom, 33.

19 For more details on the Joliet game and its aftermath see Kevin Trusty, “Angry Attack: Cubs’ Visit to Rivals Park in 1920 Marred by Stabbing,” in Radbourn’s Revenant https://radbournsrevenant.com/2018/03/24/angry-attack-cubs-visit-to-rivals-park-in-1920-marred-by-stabbing/, Trusty’s reprint of his article that originally appeared in the Joliet Herald-News on March 21, 2018, and Jacob Pomrenke, “‘You’re One of Those Crooked Chicago Ballplayers’: The Stabbing of Buck Herzog” https://jacobpomrenke.com/black-sox/youre-one-of-those-crooked-chicago-ballplayers-the-stabbing-of-buck-herzog/, originally published at TheNationalPastimeMuseum.com on April 2, 2018.

20 “Fan at Joliet Stabs Herzog of Cubs Team,” Chicago Tribune, October 1, 1920: 1; baseball historian William Lamb observes that this “scandal-incensed fan” may have confused Buck Herzog with the recently indicted Buck Weaver of the crosstown White Sox. See Black Sox in the Courtroom, 59.

21 “Fan at Joliet Stabs Herzog of Cubs Team.”

22 Black Sox in the Courtroom, 34.

23 Black Sox in the Courtroom, 59.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Phillies 3

Chicago Cubs 0

Cubs Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.